Читать книгу Apples from the Desert - Savyon Liebrecht - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction:

The Healing Power of Storytelling

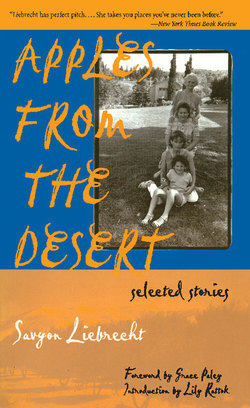

SAVYON LIEBRECHT IS considered one of the most impressive voices in contemporary Hebrew literature, and is among the most prominent women writers of fiction in Israel. She gained immediate public recognition with the publication of her first collection of short stories, Apples from the Desert, in 1986. Her maturity as a writer and her mastery of the art of short story writing were amply demonstrated in that first volume, which garnered her the Alterman Prize. Liebrecht continued to develop the short story form in her next three books, Horses on the Highway (1988), What Am I Speaking, Chinese? She Said to Him (1992), and On Love Stories and Other Endings (1995).1 (It is from her first three collections that this volume of her selected stories—the first book by Liebrecht available in English—is drawn.) Her books were favorably received by the critics, and they also became bestsellers—an unusual phenomenon for a collection of short stories.

Liebrecht’s success, in literary as well as in commercial terms, stems from the fact that she knows how to spin an intriguing story. She excels in weaving gripping plots without sacrificing psychological insight and rich symbolic meaning. The dramatic element in her stories involves a clear conflict between characters—a conflict whose significance and implications are gradually revealed and whose solution is always surprising and interesting.

The social involvement that characterizes Liebrecht’s stories undoubtedly also figures in their warm reception. Her work deals with topics on the public agenda in Israel and have contributed a measure of profundity to the current debates. Liebrecht’s eloquent and fluent linguistic style has captured the unique qualities of various social and ethnic groups, and her stories reflect the diversity of the reality evolving in present-day Israel.

Liebrecht’s stories focus on issues that are specific to Israel but at the same time, because of her great sensitivity to human suffering and distress, they also address universal themes. Nearly all of her stories demonstrate a special compassion for characters who are oppressed or disempowered in society—members of the Arab minority, Sephardic Jews (the weaker ethnic group among Israeli Jews), women, children, and aging Holocaust survivors. In fact, this ability to empathize with the victim draws in part upon the experience of the Holocaust, which is at the center of Liebrecht’s writing—and her life.

BIOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND

Savyon Liebrecht was born in Munich, Germany, in 1948, to parents who were both Holocaust survivors from Poland. She was their eldest daughter, born shortly after her parents’ liberation from concentration camps. When she was a year old, her parents brought her to Israel, where she was raised and educated.

During her military service, required of all young Israeli men and women, Liebrecht requested to serve on a kibbutz. After her discharge she went to London to study journalism. Disappointed with the level of instruction at her London school, Liebrecht returned to Israel and obtained a B.A. in philosophy and English literature. She married at the age of twenty-three and six years later had a daughter, then a son. She has raised her family in a suburb of Tel Aviv.

Liebrecht admits that she guards her privacy jealously. This fact may be connected to the silence that reigned in the house of her parents, the Holocaust survivors. This silence was born of the parents’ inability to talk about their past experiences, and of the children’s fear that their questions might open up old wounds. In a 1992 interview with the poet Amalia Argaman-Barnea, Liebrecht spoke about the “silent home”; she cited as an example of the conspiracy of silence her own reluctance to question her father about the family he had before the war. The existence of that family was revealed to her only through an old photograph in a family album, in which her father is seen smiling happily in the company of a woman and a little girl.

The wall of silence did not crumble when the writer took a trip to Poland with her parents. Even though her father made an attempt to tell her about his past life, during a train ride to Treblinka concentration camp, he did so in Polish, a language that he had never spoken to her before and that she did not understand. One can feel the anguish in her realization that “he was finally telling me his story, but to this day I have not heard it.”

In an article Liebrecht wrote about the impact of the Holocaust on her writing (125), she again emphasizes the fact that she knows practically nothing about her parents’ past: how many brothers and sisters they had, what these siblings’ names were, and what happened to them during the war. She knows that her father was incarcerated in several concentration camps, but she does not know which ones. The silence her parents maintained regarding their experiences during the Holocaust was total. Liebrecht contends that this historical lacuna resulted in children of survivors developing problems of identity.

Her family background had a significant impact on one of the major developments in Savyon Liebrecht’s professional career: the delay in the publication of her first collection of short stories. She began writing fiction at eighteen, but her first novel was rejected by a publisher and she shelved it; later, she wrote another novel, but it was also rejected by the same publisher. When she got married, she stopped writing and channeled her creativity in other directions. She studied art and sculpture at an art institute, but soon sensed that this was not the right art form for her.

When she was thirty-five, she joined a creative writing workshop under the guidance of Amalia Kahana-Carmon,2 who immediately noticed her talent and encouraged her. Kahana-Carmon submitted Liebrecht’s story “Apples from the Desert” to a literary magazine, Iton 77. Following its publication, one publishing house offered to issue a collection of her short stories. Liebrecht wrote half the stories in her first book while it was in the process of publication.

This turning point in the acceptance of Liebrecht’s work can be attributed to several factors. One is the maturation of her artistic craft in the years between the rejection of her earlier works and the enthusiastic reception of her later ones. Another is the receptiveness to the female voice that has developed in Israel only in the 1980s and 1990s, according to Rochelle Furstenberg (5). In addition, Israel’s more open attitude and its acceptance of the Holocaust, a subject that Liebrecht sees as “the biggest riddle, not only regarding my own life, but regarding the entire human existence,”3 opened before her an avenue of expression that had perhaps been blocked, both for internal and external reasons.

One must not forget, however, that a major reason for the delay in publication was Liebrecht’s deliberate decision to repress her writing impulse to satisfy the need to have a family. In many families of Holocaust survivors, this is a supreme imperative, and perhaps Liebrecht needed a new family as a power-base of security and normality. Her assertion, in the interview with Argaman-Barnea, that “I am a normal woman, living a normal life” emphasizes how much she needed this kind of solid foundation in order to obtain the freedom to soar on the wings of her imagination.

Liebrecht chose to bear children before she could dedicate herself to her art because she believes that “for a woman writer, each new book is one less baby.” She sees this as a major difference between male and female writers. Liebrecht also sees a difference between women’s wider emotional range and men’s narrower, more power-oriented range. But despite this observation, she rejects any differentiation between the writing of men and women, since, as she put it, “the hand that writes is genderless,” and she denies the existence of a discrete women’s literature.

Liebrecht’s objection to such categorization is interesting precisely because her literature belongs, in my opinion, to the domain of women’s literature. In most of her stories, the woman’s point of view is dominant, and relationships within the intimate feminine circle occupy a central position. Relationships between mothers and daughters, sisters and friends, are rendered with great depth and sensitivity, whereas relationships with men—lovers, husbands, or fathers—while also treated perceptively, are most often relegated to second place. In her stories, Liebrecht also criticizes patriarchal society for having victimized women and exploited them by denying them any position of power. The female protagonists in her stories often reveal great strength, but they are also characterized by vulnerability and compassion, and Liebrecht’s work as a whole successfully embodies the female moral code defined by Carol Gilligan as an ethics of help in distress, caring, and nurturing.

Liebrecht’s stories reflect her deep yearning for reconciliation between people placed on opposing sides of conflicts. The starting point is often a rift, an intense confrontation, that resolves itself at the conclusion with the opponents reaching a moment of grace, of rapprochement. Even though not all of Liebrecht’s stories end on a note of reconciliation, as Esther Fuchs has argued (47), they all manifest a strong, inherent need for harmony. The emotional intensity in Liebrecht’s work stems, on the one hand, from animosity and hatred often expressed in terms of warfare, and on the other hand, from a longing for unity and for a sense of belonging that overcomes the divisive forces.4 This yearning for reconciliation can be traced to several elements in the author’s biography: her exposure to the trauma of the Holocaust, her awareness of the continuous conflict in the Middle East, and—for me, of paramount importance—the fact that she is a woman, and therefore acutely sensitive to situations of distress, weakness, and vulnerability.5

BREAKING SILENCES

Liebrecht’s stories do not describe the horrors of the concentration camps; instead, they touch upon the memories of the survivors, which surface in their minds years after the liberation, tearing the veil of normality that they have striven so hard to maintain. The story “Excision,” for example, depicts the compulsive behavior of a Holocaust survivor, who chops off her grandchild’s beautiful hair just because she finds out that the child may have head lice, a fact that brings back a horrifying memory of the camps. The story’s ambiguous title (meaning both “removal” and “cutting”) indicates that the theme is not just the cutting of hair, but the cutting off, the destruction, of life in the Holocaust.

Liebrecht criticizes Israeli society, especially the relatives of survivors, for their reluctance to open their hearts to the sufferers, to listen and to empathize with the tormented souls. The conspiracy of silence that surrounds the atrocities they have endured only adds to the survivors’ anguish. In the story “Hayuta’s Engagement Party,” the granddaughter represents contemporary Israeli society, which is alienated from and impervious to the survivors’ pain. Hayuta tries to keep her loving grandfather, Grandpa Mendel, from attending a family gathering for fear that he might spoil the party with his horror stories about the concentration camps. These memories tend to resurface in his mind particularly on festive occasions, since the family gathered around set tables reminds him of those lost relatives who cannot be present at the feast. Grandpa Mendel’s daughter Bella, who understands his need to remind others of those who have perished, shudders at the thought that the old man will be excluded from the party by his own granddaughter: “We are raising monsters . . . hearts of stone!” (84). The story ends tragically, with Grandpa Mendel dying in the middle of the party after he is prevented from expressing himself on the subject of the Holocaust. The last sentence in the story encapsulates how Israeli society tries to cover up the tremendous anguish with the “sweet frosting” of the new reality: “Then [Bella] took another tissue and very gently, as if she could still inflict pain, wiped the anguished face which knew no final relief, and the handsome moustache, and the closed eyes, and the lips that were tightly pursed under a layer of sweet frosting, firmly treasuring the words that would now never bring salvation, nor conciliation, not even a momentary relief” (91–92).

Israeli society, where many Holocaust survivors found a new home, had considerable difficulty in opening up and accepting the descriptions of what the Jews of Europe had endured under the Nazis.6 This difficulty was primarily due to the unimaginable and unbearable nature of the atrocities inflicted by the Nazi exterminating machine on a defenseless, innocent population, a reality so terrible that it could hardly be conveyed in words. But apart from the depth of the atrocities themselves, there were specific components in the makeup of the young Israeli state, established in 1948 after a bloody war of independence, that contributed to the difficulty in accepting and empathizing with the survivors. The sharp contrast between the self-image of the Israeli as a fierce freedom fighter and the abject image of the Jew as a helpless victim, led to annihilation almost without resistance, gave rise to an ambivalent attitude toward the survivors.

A difficulty of another sort resulted from guilt feelings produced by the inability of those who had settled in Israel before the Holocaust to rescue their relatives left in the European communities that were later liquidated. These difficulties, compounded by a conscious decision by many survivors after liberation not to open their wounds and not to dwell on their experiences, also contributed to a repression of the Holocaust.

Further contributing to this national repression was the state’s decree of one general day of mourning to commemorate the six million Jews who had perished in the Holocaust, officially named “Day of Holocaust and Heroism.” This ritualization of the remembrance of the Holocaust was not conducive to personal expressions of sorrow and mourning, but rather helped to block them.7 While the memory of the Holocaust became a crucial element in forging a new Jewish identity, the emphasis was placed on heroism, to which only a few could lay claim, rather than on passive suffering, which reflected the personal experience of the majority of survivors. The slogan “From Holocaust to Recovery” was coined for the dual purpose of giving meaning to the victims’ suffering and providing a justification for the establishment of a new national home for them. This slogan, as well as the date set for Holocaust and Heroism Day—a week before Memorial Day and Independence Day—created, according to Handelman and Katz (83), the desired connection between the victims of the Holocaust and the victims of the struggle for the establishment of the state, thus producing an inverted process: a terrible national catastrophe leading to national redemption.

As long as the existence of the national home was threatened by neighboring countries, Israeli society was not free to deal with the issue of the Holocaust. Only in the late seventies, with the continued existence of the State of Israel relatively more secure, did the repression begin to abate, and Israeli society become ready to put the Holocaust at the center of its public agenda. Contributing to this trend of raising the legacy of the Holocaust to the center of Israeli consciousness were native Israeli writers, some of whom, like Savyon Liebrecht, were second-generation Holocaust survivors, whose personal experiences were at last receiving validation and legitimacy.8

THE SECOND GENERATION OF THE HOLOCAUST

A strong urge to belong, first to a family, then to the nascent state, is discernible throughout Liebrecht’s work, and it probably played a part in her own life as well. This need has to do with the emotional state of Holocaust survivors and their children. The traumatic separation from family and friends and the inability of the victims to protect the lives of their loved ones left deep scars on their psyches. Following the liberation from the camps, when they found out that their relatives had perished, their congregations had been annihilated, and the world they had known no longer existed, survivors were overcome by unbearable feelings of guilt, extreme loneliness, and total emptiness.

Consequently, the need to start a new family became the most compelling drive in their lives. However, the expectations the survivors had of the new family were partially thwarted, since the conditions of its creation were greatly inadequate; for the most part, couples got married in a hurry, while still in a state of shock and suffering from confusion and disintegration. Due to these circumstances, in addition to the scars left from having lived in the shadow of death, many of these new unions failed to provide the yearned-for solace and intimacy, and the wish for warmth and loving kindness went unanswered. The story “A Married Woman” presents the relationship between a husband and wife, who met by chance while looking for their lost relatives, as based on pity and desperation more than on love: “Tremendous compassion and loving kindness impelled her to touch his back gently, to quell in him the overpowering sense of despair. Then he suddenly turned back and his laughing mouth asked, ‘Shall we get married?’” (75). The couple’s daughter suffers from this compromised relationship, since neither of her parents can nourish her emotionally. “She was only eighteen, but her face was the face of a weary, miserable person” (74).

Children of survivors, born into these conditions, were particularly vulnerable. In her essay on the impact of the Holocaust on her work (128), Savyon Liebrecht claims that, in some respects, children of survivors had an even harder time than their parents. She herself was born to devastated parents who had lost everything, including their language and their culture. The inability to rebel against such parents, so as not to hurt those who had already known so much suffering, created an additional burden with which the children of survivors had to contend. Dina Wardi describes the role of children in these families: they were perceived as replacements and compensation for the relatives who had perished, and they became the central preoccupation of the parents’ lives—a state of affairs that made it difficult for the children to develop discrete, individual personalities.9

Despite the parents’ attempts to provide their children with everything and to shield them from pain, all children of the second generation knew pain and suffering. Most of the victims’ families lived in an atmosphere of dejection, anxiety, and worry, viewing their immediate environment with fear and suspicion (easily understood, in view of their past). Concern for the continued existence of the family was of the highest priority for survivors, many of whom were almost obsessively preoccupied with physical survival.10 Self-preservation and personal security were the only meaningful causes in those families. Personal happiness and creative expressions of individuality were, by and large, discounted and ignored.

This kind of troubled psychological existence pervades most of Savyon Liebrecht’s stories, not only those that directly or indirectly deal with the Holocaust.11 Her focus on the family cannot be explained simply by the central position the family occupies in Jewish tradition and Israeli society, as Atmon and Izraeli demonstrated (2); its centrality in her work must be accounted for by the experience of the second generation of the Holocaust. Liebrecht has written very little about childhood, youth, and love, and her characters are hardly ever presented as solitary figures or as couples. The family, on the other hand, is the typical arena where events take place in her stories, and it is always minutely detailed and highly charged. In “The Homesick Scientist,” for instance, the story of the relationship between the elderly uncle who has lost his son and the nephew who fills the void in the uncle’s life overshadows the intricate love story and relegates it to a secondary position. The love of the uncle and his nephew for the same girl, whom neither of them gets in the end, becomes ancillary to the unique father-son relationship that develops between the older man and the boy.

When characters in Liebrecht’s stories find themselves in a conflict, torn between family and another concern, they always prefer the family connection. This is particularly evident in the story “A Married Woman,” which explores the concealed reasons behind the powerful familial connection; not even the legal procedure of divorce can destroy the family ties.12 The woman in the story continues to care for the man she divorced under pressure from their daughter, even though he has cheated on her with other women countless times and has spent her money on drinking and gambling. The fatal connection between them, which nothing can undo or annul, is the result of their common loss of everything they had before the Holocaust. The wife is aware of this terrible truth; there is an affinity between them that cannot be repudiated, and so the relationship is maintained even though it inflicts pain on her, because her husband is all she has left that connects her to her previous life.13

In the story “Mother’s Photo Album,” the father does leave his wife and son, but it is in order to be reunited with his first wife who, unbeknownst to him, had survived the war. This is an exception that proves the rule: only previous familial ties—not love or passion, as in an affair—can supplant later familial ties. The mental illness that consequently afflicts the abandoned woman in “Mother’s Photo Album” testifies to the fact that the family served the survivors as an essential existential anchor, even when it did not satisfy many of their emotional needs.

Liebrecht’s stories underline the inability of a mother to bestow love on her children because she herself has been emotionally deprived by her equally damaged husband. Yearnings for a mother’s love, which the characters never received as children, are quite common in Liebrecht stories. In “What Am I Speaking, Chinese? She Said to Him,” the protagonist bears her mother a grudge for “the gratuitous bitterness she has injected into her life, for the poison she had accumulated in her heart over all those years, letting it fester and bubble like molten lava, locking her heart even against rare moments of sweetness” (163). Although the daughter is aware of the atrocities her mother lived through during the war, she does not understand how that trauma affected her mother’s sexuality.14

The protagonist, who never dared rebel against her mother when the latter was alive for fear that she would add to her pain and suffering, now, after the mother’s death, tries to divest herself of the depressing heritage that was bequeathed to her. She has sex with a total stranger—the real estate agent who, at her request, takes her to her parents’ old apartment, which is now for sale—in order to take revenge on her mother. In an act symbolizing her separate individuality, she makes love to the man in the exact spot where she used to hear her mother rebuff her father’s advances. This hasty, meaningless sexual encounter marks the differentiation between the daughter, who enjoys her sensuality, and the mother, who denied her physical urges. The daughter wants to prove to herself that she is capable of enjoying sex even without emotional ties, and so she seduces a stranger and makes love to him in the empty apartment, on an expensive fur coat given to her by her husband on their anniversary.15

Only after this act of rebellion can the woman begin to think about her mother with some understanding and ponder the reasons why her mother could not enjoy her own body and what lingering effects this hostility toward physical pleasure had on her. The daughter’s plea to her mother is a combination of sorrow and helpless rage: “I wonder why you never accepted the consolation of the body, why you never taught me this great conciliatory gift, this immeasurable pleasure, and I had to learn all this by myself, as if I were a pioneer” (167). Only in this extreme situation is the daughter capable of separating from her mother and father to become an individual person—although it is doubtful that this symbolic rebellion is sufficient to relieve her of the heavy burden left by her family.16

THROUGH LOVING EYES

Psychological studies examining the impact of the Holocaust on survivors’ children have demonstrated that many of them are marked by unusual sensitivity to other people’s suffering. The explanation, according to Wardi (106), is the high level of empathy these children have for their parents’ anguish. Their sense of justice regarding civil rights and the rights of minorities, disadvantaged, and deviant individuals in society is remarkably strong. Liebrecht’s identification with the victim is demonstrated in various social situations throughout her work. Her protagonists often identify with the “Other”: Arabs, Sephardic Jews, the elderly, women, children.

Particularly noteworthy is her protagonists’ ability to identify with members of the Arab minority in Israel, who suffer discrimination as a corollary of the continuous conflict between Jews and Arabs in the Middle East. The Other in this instance is a former enemy, a compatriot of the present adversary.17

Liebrecht tries to play the role of a healer, presenting possibilities for mending the rifts that threaten the existence of Israeli society. Her work describes the healing of breaches between Jews and Arabs, the building of amicable relationships, and the disappearance, at least on a small scale, of the gaps that separate Ashkenazic Jews, who constitute the elite of Israeli society, and Sephardic Jews, the disadvantaged ethnic group. Her stories offer moments of grace that span the gulfs between secular and observant Jews, between old and young. In such moments of grace, the Other is revealed as a complete human being, and a new social integration is created.

The literary paradigm by which Liebrecht constructs this vision of integration is the observation of the Other through the eyes of a representative of the ruling group. This pattern relies on strongly accentuating the motif of the observing eye, and on using the observer’s point of view as a means of effecting a change of attitude toward the object of scrutiny. The pattern comprises two stages that stand in contrast to each other: in the first stage the protagonist sees the Other in the conventional way, that is, as a different, offensive, threatening figure. In the second stage, however, the protagonist comes to realize and appreciate the Other’s unique qualities and thus regards him or her with more compassion. Readers who identify with the protagonist may thus change their own attitudes toward the Other, by seeing the Other through her loving eyes.

This literary pattern recalls Kaja Silverman’s analysis in her book The Threshold of The Visible World, in which she claims that the art form of the cinema can play an important political role in changing spectators’ attitudes toward people whom they have learned to fear or despise. Her argument is that this change may take place when the undesirable people are presented through the loving eyes of the main character in the movie. Silverman’s argument pertains mainly to changes in attitude toward people whose skin color or sexual orientation are different from the spectators’. She maintains that the success of this process depends on repeated presentations in different movies.

A similar pattern emerges in Savyon Liebrecht’s stories, since they emphasize visual elements and are based on intensive mutual observation of characters. Liebrecht’s technique favors a telling of the plot through nonverbal means, a fact that also explains her predilection for screenwriting. Liebrecht herself commented on her nonverbal sensitivity in her interview with Amalia Argaman-Barnea, connecting it to the fact that she is a daughter of Holocaust survivors: “Our home was a silent home. In a home of this type, a child learns very early on to observe and absorb clues from nonverbal sources.”

The events in Liebrecht’s story “A Room on the Roof” are conveyed largely through silences and exchanges of looks, since the characters do not really have a common language. The heroine is a young Jewish woman who is asserting her independence by having a room built on the roof of her house, using three Arab construction workers. She does not speak Arabic, and the workers’ Hebrew is broken and limited in vocabulary. The room is built against the wishes of her husband and during his absence, which results in uncommon closeness between the woman and the strange workers who find themselves inside her house.

This unexpected closeness enables the woman to get to know the most threatening Other figure in Israeli Jewish reality, under unusual circumstances. Unlike most Israeli women, who have no contact with Arabs from the occupied territories, the protagonist in this story maintains personal contact, on a daily basis, with the Arab workers in her employ. It is a very complex relationship, conducted against the background of the protracted conflict between the two peoples. Hence the woman’s fear that the Arabs may harm her, and her momentary anxiety about a possible connection between them and some acts of terrorism carried out against the civilian population in her area: “Could these hands, serving coffee, be the ones that planted the booby-trapped doll at the gate of the religious school at the end of the street? Her heart, which had been on guard all the time, began to see something, but it still didn’t know; this was just the beginning, appearing like a figure leaping out of the fog” (49).

Under these conditions, the woman’s decision to hire the Arabs to work inside her house without any male supervision evinces considerable courage. This decision can also be interpreted as a political-feminist protest against the state of affairs between the two nations, for which men are by and large responsible. Thus, the feminist project of building “a room of one’s own” is contingent on cooperation between a woman and Arabs—members of two groups of Others in Israeli society.

An element that contributes to this protest is the love that evolves between this Jewish woman and one of the Arabs, Hassan. It is a hesitant, fragile, and hopeless love, but even in its incipient, germinal existence, it points to another kind of relationship that could exist between the two peoples. The turning point in the relationship between the two main characters in the story is marked by this emergent love and by a change in the balance of power between them. While in the beginning of the story the relationship is that of conqueror and conquered, the turning point enables the characters, now finding themselves on the same level, to experience a measure of reciprocity and a true egalitarian rapport. This turning point comes with the baby’s fall from his cradle and the woman’s subsequent panic; Hassan, who has studied medicine for a couple of years, succeeds in calming down both mother and child, and thereby changes the nature of the relationship.

For the first time, Hassan speaks to the woman “without the forced humility she was familiar with” (54); for the first time he speaks to her in English, not in broken Hebrew. Even his Arabic—the language he uses when he pacifies the baby—sounds different to the woman, lyrical and fascinating. “She heard Hassan talking softly to the baby in Arabic, like a loving father talking to his child in a caressing voice, the words running together in a pleasant flow, containing a supreme beauty, like the words of a poem in an ancient language, which you don’t understand, but which well up inside you” (53–54).

At this point, it becomes apparent that Hassan is an educated, sensitive, and charming man, and he awakens in the woman warm feelings. When she compares Hassan’s gentle treatment of the baby to the cold, distant attitude of the baby’s father, she clearly prefers the stranger to her husband. Liebrecht does not invest Hassan with stereotypical qualities; he does not represent some charicature of Arab virility, but rather full, rounded humanity. The Jewish male, on the other hand, is presented as someone who has paid a heavy price for occupation and domination; he has lost the ability to maintain a viable, flowing relationship with his wife and baby.

Criticism of Israeli male aggressiveness, which supplanted the sensibility and tenderness that marked Jewish men in the past, features also in “The Road to Cedar City,” another story depicting relations between Jews and Arabs. Due to unforeseen circumstances, two families—one Jewish, one Palestinian—find themselves sharing a ride in a van while vacationing in the United States. The Jewish family consists of an older couple and their son, who is about to be drafted into the army. The Arab family consists of a young couple with their baby boy. At the end of the story, the Jewish woman, Hassida, who identifies with the Arab couple and is fascinated by their baby, decides to separate from her alienating husband and son and continue the trip in the company of her new friends.

The friendship between the two women, the Jewish and the Arab, forms almost without words; it is an affinity born out of their shared concern for the baby’s needs and well-being. The two women collaborate in caring for the baby, while the men squabble and bicker about political and military issues. During the ride, the Arab-Israeli conflict is the main topic of conversation, but the women take no part in it. They cannot tolerate the animosity between the two families and want to put a stop to it. Both women see themselves as entrusted with the task of preserving life, and they derive pleasure from taking care of the helpless baby.

Hassida’s decision to leave her husband and son results from their cruel and derisive treatment of her. The two men make fun of her sentimentality, mock her poor sense of direction, and scoff at her depressions, induced by menopause and by being cut off from her familiar surroundings. The two humiliate her in front of strangers, making her feel like a burden they would gladly be rid of at the first opportunity. In her profound distress, isolated and shunned, she suspects that “they are conspiring to drive her out of her mind, to have her locked up in prison in this strange country so they can be rid of her and go home without her” (125).

The unspoken pact between the husband and the son has changed the relationships in the family. Their newly forged male camaraderie, which replaces the tension that existed between the two when the son was young, turns the mother into an outsider and a victim. The men join forces against her, tormenting her in every possible way. Their callousness leaves her with an overwhelming sense of helplessness, which in turn gives rise to a profound empathy with the Arab minority that feels equally helpless and weak in relation to the Israeli occupier.

It is against this background that the alliance is formed between Hassida and the Arab family, which she now prefers to her own. Though it begins as a pact between the two women, it later expands to include the Palestinian man, because of his warmth and compassion toward his baby. Hassida is touched by the warm aura that envelops the Arab couple when they look at their baby. As she watches them, she feels “a radiance permeating her, as if she had witnessed a rare vision. ‘Of all the sights I have seen in America—cities, waterfalls, wide highways—this is the most beautiful’” (147). Through her loving eyes, the Others are revealed in all their splendor, utterly human and inviting.

THE POWER OF SISTERHOOD

The maternal element is a principal component in the female comradeship that Liebrecht captures so marvelously in her stories. This sisterhood has the power to overcome hostility between Jews and Arabs. It is also capable of bridging the gap that exists in Israeli society between the ruling elite, the Ashkenazic Jews, and the weaker ethnic group, the Sephardic Jews. Nurturing babies and caring for the well-being of children bring together women of different generations, disparate world views, and diametrically opposed religious beliefs. In Liebrecht’s work, women have a special and very important task: they are the guardians of life.

The story “Written in Stone” describes how the power of this kind of sisterhood overcomes differences in age, education, and mentality, and brings together women belonging to different worlds to cooperate for the sake of preserving and perpetuating life. The story centers around the relationship between an older Sephardi woman and her Ashkenazi daughter-in-law, Erella. The death of the son/husband, Shlomi, during reserve duty causes excruciating pain to both women. Erella, whose beloved husband was killed less than three months after their marriage, has difficulty coming to grips with her loss. She refuses to relinquish his place in her life and clings to Shlomi’s mother, hoping that she will acknowledge and accept her. But the bereaved mother demonstrably ignores her daughter-in-law, never granting her a word or a look.

The mother’s thundering silence is explained by the loud accusations hurled at the young widow by the older female members of the family. According to them, Erella is to blame for Shlomi’s death. This unreasonable accusation stems from an identification of Erella with the ruling establishment. It was the establishment that tore the boy away from his village and from his family, sending him to study in town in a program for gifted students. It was the promise of higher education and social advancement, the women believe, that cost the young man his life. While studying at the university, Shlomi met the Ashkenazi girl, and by marrying her, only deepened his estrangement from his family and ethnic group. Sharing his life with Erella, Shlomi no longer observed the religious commandments, and that was the reason why he was killed.19

The hostility the family shows toward Erella does not lessen over the years. There is nothing the young woman can do to change their attitude. They are not even placated by her loyalty to Shlomi’s memory, symbolized by the fact that she never removes the wedding ring he gave her. Even the fact that she faithfully shows up at his mother’s house every year on the anniversary of his death does not soften the hearts of the women of the family. When she remarries and becomes pregnant, the mother asks her to stop coming to her house, but the young woman does not accede to her demand and continues to come, hoping that her suffering will alleviate her guilt and sorrow.20

The turning point in the story comes only years later, when Erella herself has joined the circle of bereaved mothers after the death of her own daughter from her second marriage, who was named Shlomit after the dead Shlomi. The old woman breaks her silence and talks to her daughter-in-law only now, when Erella is married for the third time and pregnant again. This time the old woman is determined to remove the young woman from the circle of death, so that the fetus in her womb may have a chance to live. In order to persuade her, she shows her a love letter that Shlomi wrote to Erella, returned to her by the army authorities with his belongings after he was killed. The reason she gives for never forwarding the letter explains the motive behind her cold attitude toward her daughter-in-law. “A mother, her son dies—she dies. A wife, her husband dies—she lives” (115).

Erella is shocked by this explanation, which sheds new light on the troubled relations between them. She is astounded by a new realization: “All these years you wanted to protect me” (117). The old woman’s attempts to keep her away from the family, from the house of mourning, suddenly assume a new significance. To her amazement, she learns that her mother-in-law, too, was a young widow, and that her first husband’s name was also Shlomo. Now Erella comprehends the old woman’s guilt for having named her son Shlomi, after her first husband—a name that, according to her belief, brought him death.

Erella now understands the old woman’s admonition not to name her new baby after Shlomi, because this is a “name written in stone,” on a grave (117). Erella realizes the profound logic of putting a boundary line between the living and the dead. The wisdom of generations and a bitter personal experience have prompted the old woman to try and keep her away from the forbidden territory. One cannot build a new life in the shadow of a life that was cut off; one has to find the spiritual strength to tear oneself away and begin anew.

The story concludes with a description of the profound change that has taken place within Erella: “Today she had been set free! This woman had the power to release her from the vow that neither of them had ever understood. And she had done it. The old woman had let her go” (117). Her pregnancy, so burdensome to her before, now fills her whole being with unfamiliar happiness. She feels wondrously weightless, “as if her body were made of light” (118). Liebrecht breaks away from the stereotypical pattern of a mother-in-law envious of her young daughter-in-law, and instead describes the pact between the two as a bond between mothers. In “Written in Stone,” this bond overcomes the gap between the Sephardic culture and the Ashkenazic, and focuses on an Israeli common denominator—fostering the next generation.21

FEMINIST PROTEST

A more extreme protest against the disfranchisement of women by the patriarchal religious establishment is found in the most feminist of Liebrecht’s stories, “Compassion.” The ironic title refers to the misfortunes of the female protagonist, Clarissa, a Holocaust survivor who was hidden in a convent during the war years and afterward came to Israel. The transition from an orthodox Jewish home to a Christian convent and then to a secular kibbutz in Israel totally undermined her sense of belonging, so when she later fell in love with an Arab, she went to live with him in his village. After she had borne him children, the husband demanded that she marry an old uncle of his, so that he could marry a younger wife. Her refusal to comply did not stop him from marrying the woman anyway, since as a Moslem he was allowed to have four wives. Still, the husband punished her by locking her up in a shack and keeping her totally isolated.22

Clarissa’s predicament does not break her spirit, but when she finds out that her husband and her son are about to murder her daughter because she refused to marry an old man, preferring her young beloved, Clarissa is gripped by a powerless rage. From her place of confinement, she sees her husband and son setting out on their murderous expedition, and she is prepared to kill them in order to prevent them from carrying out their scheme. “Had she been free and light-footed, had she had a knife in her hand, she would have sped after them on the mountain slope to stick the knife in their backs, withdrawing it and plunging it in again and again until they sank dead at her feet” (193).

The isolated, abused, and humiliated woman knows that nobody will come to her aid. In the village she is considered a “witch” and is ostracized for her rebelliousness. The women in the Arab village are resigned to the absolute sway their men have on their lives, as dictated by Islamic law; they will not come to the rescue of this woman or her rebellious daughter. The villagers mock her, saying, “She used to be a Jew, she used to be a Christian, and she used to be a Moslem—not one God wanted her” (196).

Clarissa resolves to kill her cruel son’s two-month-old daughter, entrusted to her care because the baby’s mother is ill. The grandmother’s decision to drown her little grandchild in a well is a horrendous deed that combines both revenge on her son and compassion for his daughter. Death is preferable to a woman’s existence in this kind of reality, Clarissa thinks. She sees herself as performing an act of charity—a mercy killing. She cleans the baby, feeds her, and hugs her, making her last moments as pleasant as possible, then gently puts her in the water.

The murder, which to some extent is also a symbolic suicide, is an act of desperation, meant to spare the little girl the suffering that is every woman’s lot in the Arab village: “the homelessness, the helplessness, her father and her brothers and her uncles, her husband and her husband’s brothers and her sisters’ husbands, who would close in around her, the household chores from one night to the next, the loneliness, the heart fluttering, encased in the body, the man in her bed, rolling her over as he wished, coming into her as into a wound, and the fear for her daughters and their spilled blood” (200).

This description attests to Liebrecht’s unique ability to explore a foreign reality and to grasp, with great sensitivity, what takes place there. She gives expression to the suffering of women in the Arab village, but without purporting to fully understand it. By making the protagonist a Jew who married a Moslem of her own free will, Liebrecht deliberately eschews “speaking for the ‘Other.’”23 Against this alien background, she is able to depict a woman in distress so extreme that it produces a horrendous reaction, and to make an emphatic protest against the kind of conditions in which infanticide might be understood as an act of loving kindness.

FEMINIST REVISION

In her first published story, “Apples from the Desert,” Savyon Liebrecht has pointed to a possible way out of the impasse that faces every woman in patriarchal society. Rivka, the young heroine of the story, recognizes the need to free herself from economic dependence on men in order to achieve equality with them. She joins a kibbutz, where she works for a living and is independent in every respect.24 Her decision to live with the man she loves without marriage is meant to ensure her absolute emotional freedom as well. For Rivka, her move is a revolutionary one, since the secular, basically Ashkenazic kibbutz is so different from the traditional, Sephardic community in which she grew up. Her decision is an expression of her rebellion against her father, who has ignored her all her life, thought she was an inferior specimen of womanhood, and tried to find a match for her without even consulting her.

In fact, Rivka’s departure from home is a concealed rebellion, since she never confronts her father. The confrontation takes place via her mother, Victoria, who comes to the kibbutz in order to bring her rebellious daughter home. But Victoria betrays the mother’s traditional role, dictated by the patriarchal system, of making daughters conform and accept male domination. Victoria not only fails to quell her daughter’s rebellion; she actually colludes with Rivka in keeping the father in the dark about what is going on. This surprising development has several causes. The first is Victoria’s rediscovery of her daughter through the eyes of the young man with whom Rivka lives. Victoria is moved by the way her daughter has blossomed and is amazed at the changes in her. Another reason is her identification with the young couple’s love, viewed against her own missed opportunity in her youth, an episode she recalls upon witnessing her daughter’s loving relationship.

Victoria decides to help her daughter realize her dream of a love-filled life, and not let Rivka languish, as she herself has, in a cold, loveless marriage. The bond between the women allows Rivka to help her mother gain a measure of freedom and independence, and at the same time allows Victoria to protect her daughter and offer her emotional support. Victoria’s decision to become her daughter’s ally is motivated by a symbolic dream she has in which the image of the lost beloved of her youth is merged with the image of the young man who wishes to marry Rivka. In the dream, this composite figure appears in the Garden of Eden, hinting at the wondrous nature of love. The apple held in the figure’s hand turns out to be “precious stones,” indicating the riches that love harbors (71).

But “Apples from the Desert” is a subversive story not only by virtue of its plot. It also employs “emancipatory strategies,” as defined by Patricia Yaeger. The suggestive title of the story highlights the motif of the apple, linking it through the dream to the Genesis story of the Garden of Eden. But Liebrecht’s Garden of Eden is an inversion of the biblical one; sexuality is not a sin here, and the woman is not viewed as responsible for the expulsion from paradise for having tempting the man to eat the apple. This is a sensual paradise, where the sin punishable by expulsion is the refusal to heed the call of love. Here it is the man who offers an apple to the woman, and she who must recognize its power.

The power that grows apples in the desert is the power of devoted love. The story creates an analogy between growing apples in the desert and making it bloom and the blossoming of Rivka, whose life was a wasteland as long as she lived in Jerusalem among family members who did not appreciate her virtues. Only when she found love did she become handsome—“milk and honey,” as her mother says. This expression, used in the Bible to describe the land of Israel as “the land of milk and honey,” creates an analogy between the love of the land and the love of a man for a woman. Liebrecht depicts an ideal reality, where love and fertility coexist in the image of a kibbutz named “Neve Midbar” (oasis). The heroine’s name, Rivka, also has symbolic overtones, since it recalls the independent spirit of the Biblical Rebecca, as discussed by Nehama Ashkenazi (12); the mother’s name, Victoria, underlines the triumph of sisterhood over patriarchy.

THE HEALING POWER OF STORYTELLING

This first publication in English of Savyon Liebrecht’s selected stories is indeed an important event. For readers outside of her native land, Liebrecht’s stories provide essential insights into contemporary Israeli society. But as really fine literature does, they also reach toward deeper truths that know no national boundaries. Liebrecht’s protagonists, in their own ways, commit quiet acts of courage or achieve small epiphanies of understanding, which change and often enlarge them as human beings—and through her fiction, she offers her readers the opportunity to do the same.

Liebrecht’s skill as a writer, combined with her perceptiveness, her compassion, and her deep humanity, create a body of work that is testament to the healing power of storytelling. It is a power that can help to close old wounds, to inspire new levels of empathy and understanding, to build bridges across the chasms that divide people—to make apples grow even in the desert.

Lily Rattok

Tel Aviv

March 1998

NOTES

1. In her youth, Liebrecht wrote two novels that were rejected by the publisher she approached, but her mature output in fiction consists entirely of short stories. Liebrecht has also written prize-winning film scripts, and one of her short stories has been made into a play.

2. Amalia Kahana-Carmon is one of the central figures in modern Hebrew literature, and, in my opinion, one of the two founding mothers of Israeli women’s literature (see Rattok, xx–xxv). A strong friendship formed between the well-known author and the fledgling writer, although it should be noted that Kahana-Carmon’s artistic influence on Liebrecht has gradually diminished over the years.

3. Quotations in this and the subsequent two paragraphs come from Liebrecht’s 1992 interview with Amalia Argaman-Barnea.

4. In two stories, “Written in Stone” and “Dreams Lie,” the dynamics are of hostility giving way to reconciliation. “Dreams Lie” (from the collection Apples from the Desert), contains descriptions of an astonishing physical struggle between an old woman and her granddaughter. “Like two blind women, their fingers clutched at each other’s throats, grabbing hold of it with hatred, with a true intention to hurt, to beat unconscious, to cleanse the body from the malice that seeps through the hands and thrashes frantically.” In “Written in Stone,” the violence is mental: Erella prepares to meet her dead husband’s relatives, “whose eyes flashed daggers at her”; she imagines that they wait for her “with eyes like hidden traps” (99).

5. In the interview with Amalia Argaman-Barnea, Liebrecht said that women cope much better than men in situations that are beyond their control, and that a sense of helplessness may lead directly to insanity. Consequently, one expects women to feel compassion—the most important element in the feminist ethos, according to Lugones and Spelman (1987: 235).

6. This difficulty is presented in the stories “Excision” and “Hayuta’s Engagement Party” through the figures of the daughters-in-law. Savyon Liebrecht, in her essay on the Holocaust’s influence on her writing (128), justified her use of these figures as the vehicles for venting aggression toward the survivors; according to her, the children of the victims would never dare utter the words said by the daughters-in-law in the stories. Only those family members who did not grow in the shadow of the Holocaust could do so.

7. An example of the problematic function of Holocaust and Heroism Day in Israeli reality can be found in “Hayuta’s Engagement Party,” in the words of the survivor’s daughter-in-law when she tries to shut him up. “Don’t we have Memorial Day and Holocaust Day and commemorative assemblies and what have you? They never let you forget for a minute. So why do I need to be reminded of it at every meal?” (88)

8. In the article “The Holocaust in Hebrew literature: Trends in Israeli Fiction in the Eighties,” Avner Holtzman writes that he considers Savyon Liebrecht one of the most important writers in this respect (24).

9. Wardi calls children of Holocaust survivors “memorial candles,” underlying their role in preserving the memory of relatives who perished in the war. It is this role that makes the natural separation during adolescence so painful for the parents, resulting in difficulty in individuation for the children. Savyon Liebrecht overcame this difficulty by requesting to work on a kibbutz during her miliary service and, particularly, by going to London to study immediately after her discharge. Her father was angry at her and would not talk to her for a year after she left, even though she was almost twenty at the time.

10. The main characters in “Dreams Lie” and “General Montgomery’s Victory” (published in the collection On Love Stories and Other Endings) are both grandmothers who channel all their efforts and energy to preparing food and nourishing their grandchildren in order to ensure their health and well-being.

11. The most direct descriptions of the Holocaust are found in Liebrecht’s third collection of short Stories, What Am I Speaking, Chinese? She Said to Him (1992), particularly in the stories “Morning in the Park with the Nannies” and “The Strawberry Girl.” The majority of her stories, however, present echoes that the trauma of the Holocaust left in the survivors’ souls, either through memories or as an ideological position. For example, in the story “Pigeons,” which appeared in Apples from the Desert, the protagonist loses her faith in God as a result of the atrocities she has lived through, and becomes active in a movement fighting religious coercion, claiming that “God went up in smoke in the chimneys of Auschwitz.”

12. In “A Married Woman,” there is a sharp juxtaposition between the story’s title and the opening sentence, which presents the main character as a divorced woman. “Only when the divorce bill lay in her hand did Hannah Rabinsky remove her wedding picture from the wall next to her bed” (73). That photograph is the symbolic expression of a survivor’s yearning to have a family and to live a normal life, and it is more powerful than the legal document, the letter of divorce. It is clear from the events in the story that the title conveys a profound truth; Hannah remains a married woman even though she has divorced her husband. One can see “A Married Woman” as a negative image of S. Y. Agnon’s story “Metamorphosis.” Both stories open with a description of a divorce proceeding, and both allude to a reversal at the end. However, in Liebrecht’s story, “the marriage wasn’t really a marriage and the divorce won’t really be a divorce” (78).

13. A somewhat similar pattern of relationships is portrayed in the story “A Love Story Needs an Ending” (from the collection Love Stories and Other Endings), in which the protagonist, a Holocaust survivor, cheats on his devoted wife. The wife is resigned to her lot, but agonizes over what she regards as the betrayal of her daughter. After the father’s death, the daughter decides to take revenge on one of the women he has loved, whose love affair with her father she witnessed as a child. That affair was a source of anxiety for her, since she feared that her father might be enticed by the bewitching power of love to step outside the family circle, and so she tried to prevent him from leaving by using childish ruses. In this story, the Oedipal elements in the father-daughter relation are prominent, discernible when the mother tells her daughter, “Sometimes I thought that it was not normal, the way you loved him. Perhaps this should not be between father and child, such love.” (Similar elements can be found in subtler form stories such as “What Am I Speaking, Chinese? She Said to Him.”) Dina Wardi points out that such relationships are not uncommon in families of survivors; the father often turns to the daughter for the fulfillment of emotional needs because of the mother’s precarious mental state, steeped in chronic mourning and depression.

14. Wardi cites research showing that women who suffered during the Holocaust had difficulties functioning emotionally and sexually with their husbands.

15. Unlike Leon Yudkin, who interprets the incident as a failed attempt on the daughter’s part to reconcile her parents to each other (178), I see it as the daughter taking a position with her sensuous father against the mother who denied her sexuality. Moreover, it is a failed attempt to wipe out the stains of the past, symbolically represented by the stains on the bedroom ceiling, which the mother implores the father to blot out. The stains of the past, indelibly lodged in the depth of the mother’s psyche, have left scars on the daughter as well. This is not a story about “lack of communication,” as Yudkin has claimed, but a work describing the insurmountable difficulty of understanding the survivors, who forever feel as if they were speaking Chinese to those around them.

16. Many characters in Liebrecht’s stories suffer from an inability to forge for themselves a unique individual identity, because they bear the brunt of their parents’ past on their shoulders. According to Wardi (40), this difficulty is characteristic of the second generation of survivors, due to the parents’ expectations that their children will stand in for family members who have perished, and also that they will fulfill the aspirations that they themselves were unable to realize because of the war. Thus, the second generation is saddled with the dual task of “pulling a hearse” and of carrying out the “youthful wishes” of the survivors. This heavy burden lies on the shoulders of the protagonist of Liebrecht’s ars poetica story “To Bear the Great Beauty” (published in the collection Apples from the Desert). Even though the mother in the story is not presented as a Holocaust survivor, her severe medical condition and the death of all her immediate relatives in a disaster serve as a “camouflage” in this respect. The mother who suffers from depression, untreated chronic mourning, and an inability to relate even to the people closest to her, is in fact characterized by “survivor’s syndrome,” defined by psychologists as the emotional condition of concentration-camp survivors. (See, for example, W. G. Niderland.) Her son, the protagonist, feels that he has to carry, for her sake, the memory of her dead relatives and, at the same time, write the poems that she herself was unable to produce because of the traumas she has suffered.

17. The protagonist of the story “Reserve Duty,” from the collection Apples from the Desert, is not content with merely wishing for peace and with working diligently and clandestinely to bring it about; he is willing to cross the line that separate the two peoples, to come and live in the Arab village as one of its native sons. This urge to “desert his nation,” to immerse himself in the world of the Other, comes over him at the least expected or appropriate moment: when he enters the village as the commander of an army detail searching for indigenous persons suspected of hostile activity.

It is important to note that Liebrecht is not the first nor the only writer in Hebrew literature to express guilt feelings vis-à-vis the Arab minority in Israel. According to Benjamin Tammuz and Leon Yudkin (16), Hebrew literature has been dealing with these feelings for many years now. The best known stories in this respect are S. Yizhar’s “The Prisoner” and “Hirbet Hiz’ee.”

A. B. Yehoshua, in the story “Facing the Forests,” describes the dissolution of the Zionist enterprise by an Arab and a Jew who collaborate in the act of destruction. The Jewish forest ranger whose mission is to watch over the symbolic forest sets fire to it, in collaboration with an old Arab who has found refuge in the forest. Thus, the old Arab avenges the destruction of his village during the war of independence and the obliteration of its site by the planting a forest on its ruins. The young Israeli joins him out of a desire to rebel against his parents, who have subjugated his life to a cause sacred to their heart—the guarding of the forest (the State) that they have created. (For a detailed analysis of Yehoshua’s story, see Gila Ramraz-Rauch, 128–40).

Yehoshua’s story is more extreme than any of Liebrecht’s, both in its violent tone and in its political implications. It not only gives vent to the guilt feelings of the younger generation in Israel, but also warns against a destructive eruption that threatens the entire Zionist enterprise because it has ignored the needs of the Arab minority. Liebrecht, on the other hand, is interested mostly in expressing the malaise of conscientious Jews, escaping to an unrealizable, momentary fantasy about resuming a harmonious relationship between Jews and Arabs. The dream of forming an alliance, of creating a brotherhood between Jews and Arabs, expresses the profound need to overcome the power struggle and the animosity that exist between the two peoples.

18. This is in contrast to the presentation of the Arab as the epitome of sexual attraction in Amos Oz’s “My Michael,” where he remains voiceless. Liebrecht grants the Arab in her story a more humane and complex presence.

19. The fierce tension between the Sephardic culture and the dominant Ashkenazic culture in Israel is described in Ella Shohat’s Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation (115–78).

20. The mourning customs of the various ethnic groups in Israel are described in Phyllis Palgi’s book Death, Mourning, and Bereavement in Israel.

21. Sisterly bonding that transcends the deep chasms between orthodox and secular Jews in Israeli society is the theme of Liebrecht’s story “Purple Meadows” (published in the collection “What Am I Speaking, Chinese?” She Said to Him). The friendship that develops between two women whose lifestyles and world views are so different is motivated by a wish to rehabilitate the shattered life of a little girl. The girl’s life fell apart when her mother was raped and consequently became pregnant. The rabbis instructed her to abort the fetus, divorce her husband, and sever all ties with her daughter. This woman is, in fact, a victim of a double rape: the physical rape perpetrated on her body by a strange man, and the more horrendous spiritual rape perpetrated by members of her congregation under the instructions of the patriarchal religious establishment. Here, the affinity between the women is based on another element—on the bond created by female vulnerability. (The traits and practices of the ultra-Orthodox Haredi community are described by Menachem [130–33].)

22. Risa Domb discusses the patriarchal structure of Arab society in The Arab in Hebrew Prose, 1911–1948 (29).

23. This is how Gunew and Spivak define the (in their opinion) reprehensible attempt to represent marginal groups through “token figures” (416).

24. The status of women in the kibbutz is succinctly described by Calvin Goldscheider (162–63) and by Judith Buber-Agassi (395–421).

WORKS CITED

Agnon, S.Y. “Metamorphosis.” In Twenty-One Stories. New York: Schocken, 1970.

Ashkenazi, Nehama. Eve’s Journey: Feminine Images in Hebraic Literary Tradition. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986.

Azmon, Yael and Dafna N. Izraeli., eds. Women in Israel: Studies of Israeli Society. New Brunswick, N.J., and London: Transaction Publishers, 1995.

Buber-Agassi. Judith. “Theories of Gender Equality: Lessons from the Israeli Kibbutz.” In Azmon, Yael and Dafna N. Izraeli., eds. Women in Israel: Studies of Israeli Society. New Brunswick, N.J., and London: Transaction Publishers, 1995,395–421.

Domb, Risa. The Arab in Hebrew Prose, 1911–1948. London: Valentine, Mitchell, 1982.

Friedman, Menachem. “Life Tradition and the Book: Tradition in the Development of Ultra-Orthodox Judaism.” In Israeli Judaism, edited by Shlomo Deshen, Charles S. Liebman, and Moshe Shokied. New Bruswick, N.J. and London: Transaction Publishers, 1995, 127–44.

Fuchs, Esther. “Apples from the Desert.” In Modern Hebrew Literature 3–4 (Spring 1988): 46–47.

Furstenberg, Rochelle. “Dreaming of Flying: Women’s Prose of the Last Decade.” In Modern Hebrew Literature 6 (Spring/Summer 1991): 5–7.

Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Goldscheider, Calvin. Israel’s Changing Society: Population, Ethnicity, and Development. Boulder, Co.: Western Press, 1996.

Gunew, Sneja and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. “Questions of Multiculturalism.” In Women’s Writing in Exile, edited by Mary Lynn Broe and Angela Ingram. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1989, 412–20.

Handelman, Dov and Elihu Katz. “State Ceremonies of Israel: Remembrance Day and Independence Day.” In Israeli Judaism, edited by Shlomo Deshen, Charles S. Liebman, and Moshe Shokied. New Brunswick, N.J., and London: 1995,75–85.

Holtzman, Avner. “The Holocaust in Hebrew Literature: Trends in Israeli Fiction in the 1980s.” Modern Hebrew Literature 8–9 (Spring/Fall 1992): 23–27.

Liebrecht, Savyon. Apples from the Desert (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv: Sofriat Poalim, 1986.

———. “The Influence of the Holocaust on My Work.” In Hebrew Literature in the Wake of the Holocaust, edited by Leon Yudkin. Rutherford, Madison, and Teaneck, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London and Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1993, 125–30.

———. Interview with Argaman-Barnea, Amalia (in Hebrew). Yediot Ah’ronot, 6 May 1992.

———. Horses on the Highway (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv: Shifrat Poalim, 1988.

———. On Love Stories and Other Endings (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Keter, 1995.

———. What Am I Speaking, Chinese? She Said to Him (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Keter, 1992.

Lugones, Marcia and Elizabeth V. Spelman. “Competition, Compassion, and Community: A Model for a Feminist Ethos.” In Competition: A Feminist Taboo? edited by Valerie Miner and Helen E. Longino. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1987, 234–47.

Niderland, W. G. “Clinical Observation on the ‘Survivor Syndrome’: Symposium on Psychic Traumatization Through Social Catastrophe.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis 49 (1968): 313–31.

Oz, Amos. My Michael. London: Chatto and Windus, 1975.

Palgi, Phyllis. Death, Mourning, and Bereavement in Israel. Jerusalem: Jerusalem Academic Press, 1973.

Ramraz-Rauch, Gila. The Arab in Israeli Literature. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press; London: I. B. Tauris, 1989.

Rattok, Lily and Carol Diamant, eds. Ribcage: Israeli Women’s Fiction. New York: Hadassah, 1994.

Shohat, Ella. Israeli Cinema: East/West and the Politics of Representation. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989.

Silverman, Kaja. The Threshold of the Visible World. New York and London: Routledge, 1996.

Tammuz, Benjamin and Leon Yudkin, eds. Meetings with the Angel. London: Andre Deutch, 1974.

Wardi, Dina. Memorial Candles: Children of the Holocaust. New York and London: Routledge, 1992.

Yaeger, Patricia. Honey-Mad Women: Emancipatory Strategies in Women’s Writing. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

Yehoshua, A. B. “Facing the Forests.” In Three Days and a Child. New York: Doubleday, 1970.

Yizhar, S. “The Prisoner” and “Hirbet Hiz’ee.” In Modern Hebrew Literature, edited by Robert Alter. New York: Behrman House, 1975.

Yudkin, Leon. A Home Within: Varieties of Jewish Expressions in Modern Fiction. Northwood, Middlesex: Spence Reviews, 1996.

Translated from the Hebrew by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman