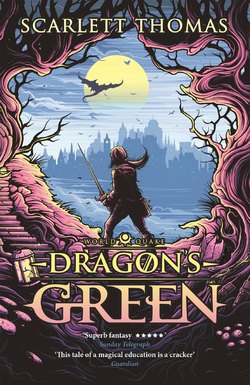

Читать книгу Dragon's Green - Scarlett Thomas - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Mrs Beathag Hide was exactly the kind of teacher who gives children nightmares. She was tall and thin and her extraordinarily long fingers were like sharp twigs on a poisonous tree. She wore black polo necks that made her head look like a planet being slowly ejected from a hostile universe, and heavy tweed suits in strange, otherworldly pinks and reds that made her face look as pale as a cold moon. It was impossible to tell how long her hair was, because she wore it in a tight bun. But it was the colour of three – maybe even four – black holes mixed together. Her perfume smelled of the kind of flowers you never see in normal life, flowers that are very, very dark blue and only grow on the peaks of remote mountains, perhaps in the same bleak wilderness as the tree whose twigs her fingers so resembled.

Or, at least, that was how Maximilian Underwood saw her, on this pinkish, dead-leafy autumnal Monday towards the end of October.

Just her voice was enough to make some of the more fragile children cry, sometimes only from thinking about it, late at night or alone on a creaky school bus in the rain. Mrs Beathag Hide was so frightening that she was usually only allowed to teach in the Upper School. Everything she most enjoyed seemed to involve untimely and violent death. She particularly loved the story from Greek mythology about Cronus eating his own babies. Maximilian’s class had done a project on the story just the week before last, with all the unfortunate infants made from papiermâché.

Mrs Beathag Hide was actually filling in for Miss Dora Wright, the real teacher, who had disappeared after winning a short-story competition. Some people said Miss Wright had run away to the south to become a professional writer. Other people said she’d been kidnapped because of something to do with her story. This was unlikely to be true, as her story was set in a castle in a completely different world from this one. In any case, she was gone, and now her tall, frightening replacement was calling the register.

And Euphemia Truelove, known as Effie, was absent.

‘Euphemia Truelove,’ Mrs Beathag Hide said, for the third time. ‘Away again?’

Most of this class, the top set for English in the first form of the Tusitala School for the Gifted, Troubled and Strange (the school, with its twisted grey spires, leaky roofs, and long, noble history, wasn’t really called that, but, for various reasons, that was how it had come to be known), had realised that it was best not to say anything at all to Mrs Beathag Hide, because anything you said was likely to be wrong. The way to get through her classes was to sit very still and silent and sort of pray she didn’t notice you. It was a bit like being a mouse in a room with a cat.

Even the more ‘troubled’ members of the first form, who had ended up in the top set through cheating, hidden genius or just by accident, knew to keep it buttoned in Mrs Beathag Hide’s class. They just hit each other extra hard during break time to make up for it. The more ‘strange’ children found their own ways to cope. Raven Wilde, whose mother was a famous writer, was at that moment trying to cast the invisibility spell she had read about in a book she’d found in her attic. So far it had only worked on her pencil. Another girl, Alexa Bottle, known as Lexy, whose father was a yoga teacher, had simply put herself into a very deep meditation. Everyone was very still and everyone was very silent.

But Maximilian Underwood hadn’t, as they say, got the memo.

‘It’s her grandfather, Miss,’ he said. ‘He’s ill in hospital.’

‘And?’ said Mrs Beathag Hide, her eyes piercing into Maximilian like rays designed to kill small defenceless creatures, creatures rather like poor Maximilian, whose school life was a constant living hell because of his name, his glasses, his new (perfectly ironed) regulation uniform, and his deep, undying interest in theories about the worldquake that had happened five years before.

‘We don’t have sick grandparents in this class,’ said Mrs Beathag Hide, witheringly. ‘We don’t have dying relatives, abusive parents, pets that eat homework, school uniforms that shrink in the wash, lost packed lunches, allergies, ADHD, depression, drugs, alcohol, bullies, broken-down technology of any sort . . . I do not care, in fact could not care less, how impoverished and pathetic are your unimportant childhoods.’

She raised her voice from what had become a dark whisper to a roar. ‘WHATEVER OUR AFFLICTIONS WE DO OUR WORK QUIETLY AND DO NOT MAKE EXCUSES.’

The class – even Wolf Reed, who was a full-back and not afraid of anything – quivered.

‘What do we do?’ she demanded.

‘We do our work quietly and do not make excuses,’ the class said in unison, in a kind of chant.

‘And how good is our work?’

‘Our work is excellent.’

‘And when do we arrive for our English lesson?’

‘On time,’ chanted the class, almost beginning to relax.

‘NO! WHEN DO WE ARRIVE FOR OUR ENGLISH LESSON?’

‘Five minutes early?’ they chanted this time. And if you think it’s not possible to chant a question mark, all I can say is that they did a very good job of trying.

‘Good. And what happens if we falter?’

‘We must be stronger.’

‘And what happens to the weak?’

‘They are punished.’

‘How?’

‘They go down to Set Two.’

‘And what does it mean to go down to Set Two?’

‘Failure.’

‘And what is worse than failure?’

Here the class paused. For the last week they had been learning all about failure and going down a set and never complaining and never explaining and how to draw on deep, hidden reserves of inner strength – which was a bit frightening but actually quite useful for some of the more troubled children – and not just being on time but always five minutes early. This is, of course, impossible if you are let out of double maths five minutes late, or if you have just had double P.E. and Wolf and his friends from the Under 13 rugby team have hidden your pants in an old water pipe.

‘Death?’ someone ventured.

‘WRONG ANSWER.’

Everyone fell silent. A fly buzzed around the room and landed on Lexy’s desk, and then crawled onto her hand. In Mrs Beathag Hide’s class you prayed for flies not to land on you, for shafts of sunlight not to temporarily brighten your desk, for – horrors – your new pager not to beep with a message from your mother about your packed lunch or your lift home. You prayed for it to be someone else’s desk; someone else’s pager. Anyone else. Just not you.

‘You, girl,’ said Mrs Beathag Hide. ‘Well?’

Lexy, like most people who have just come out of a deep meditation, could only blink and stare. She realised she had been asked a question by this incredibly tall person and . . .

She had no idea of the answer, or even, really, the question. Had she been asked what she was doing, perhaps? She blinked again and said the first thing – the only thing – that came into her mind.

‘Nothing, Miss.’

‘EXCELLENT. That’s right. NOTHING is worse than failure. Go to the top of the class.’

And so for the rest of the lesson, Lexy, who ideally just wanted to be left alone, had to wear a gold star pinned to her green school jumper to show she was Top of the Class, and poor Maximilian, who couldn’t even remember exactly what he’d done wrong, had to sit in the corner wearing a dunce’s hat that smelled of mould and dead mice because it was a real, antique dunce’s hat from the days when teachers were allowed to make you sit in the corner wearing a dunce’s hat.

Were teachers allowed to do this now? Probably not, but Mrs Beathag Hide’s pupils were not exactly queuing up to be the one to report her. Maximilian, despite being one of the more ‘gifted’ children, was often Bottom of the Class, and now he was on the verge of being sent down to Set Two. The only person doing worse than Maximilian was Effie, and she wasn’t even there.