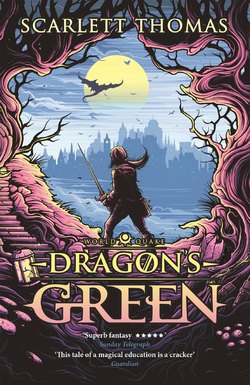

Читать книгу Dragon's Green - Scarlett Thomas - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

The reason Effie had not yet arrived at school that Monday morning in October was because of what had happened the previous Wednesday night. Her father, Orwell Bookend, had come to pick her up from her grandfather’s as usual, but instead of waiting in the car he had come up the two flights of stairs to Griffin’s rooms.

Effie had been sent to the library ‘to study’, but she had hung around in the corridor to try to hear what her father said. She knew something was going on. The week before, Griffin had unexpectedly gone away for three days and she’d had to go straight home after school to help her step-mother Cait with her baby sister Luna instead of studying with her grandfather.

Orwell Bookend had once worn gold silk bow ties and waltzed Effie’s mother around their small kitchen, singing her songs in the lost languages he used to teach. But less than two years after Aurelia’s disappearance, he had started seeing Cait. Then everything changed at the university and he got a promotion that meant he wore dark suits, often with a name badge, and had to go to conferences called things like ‘Offline Learning Environments’ and ‘Back to Pen and Paper’.

‘It’s happened again,’ he had said to Griffin on that Wednesday evening. ‘Your stupid Swords and Sorcery group has written to me. They say you are teaching her “forbidden things”. I don’t know what that even means, but whatever it is, I want you to stop.’

Griffin was silent for a long time.

‘They are wrong,’ he said.

‘I don’t care,’ said Orwell. ‘I just want you to stop.’

‘You’ve never believed in the Otherworld,’ Griffin said. ‘And you think the Guild just administers something like an elaborate game. Fine. I accept that. So why do you care what I teach her? Why do you care what they say?’

‘It doesn’t have to be real to be dangerous,’ said Orwell.

‘Fair enough,’ said Griffin quietly. ‘But all I ask is that you trust me. I have not gone against the ruling of the Guild. Effie is quite safe. Or at least as safe as anyone else is in the world now.’

There was a long pause.

‘I never knew where Aurelia had really gone when she said she’d been to the “Otherworld”,’ said Orwell. ‘But I’m sure it was all a lot more down-to-earth than she made out. In fact I’m certain it simply involved another man, probably from this ridiculous “Guild”. Yes, I know you believe in magic. And maybe some of it does work, because of the placebo effect, or . . . Look, I’m not completely cynical. Obviously Aurelia wanted me to believe in it all, but I just never could. Not on the scale she was talking about.’

Effie could hear footsteps; probably her father pacing up and down. He continued speaking.

‘I don’t know where Aurelia is now. I’ve accepted that she’s gone. I assume she is dead, or with this other man. I don’t even know which I’d prefer, to be honest. But I am not having my daughter get involved with the people who corrupted her. It’s a world full of flakes and lunatics and dropouts. I don’t like it. Do you understand?’

Griffin sighed so loudly Effie could hear it from the corridor.

‘Look,’ he began. ‘The Diberi . . . They . . .’

Orwell swore loudly. There was the sound of him hitting something, perhaps the wall. There were then some quiet words Effie could not pick out. Then more shouting.

‘I don’t want to hear about the Diberi! They DO NOT exist in real life! I’ve already said that I . . .’

‘Well then, you won’t find out what is happening now,’ said Griffin, mildly.

Later that night Griffin Truelove was found bleeding, unconscious and close to death in an alleyway on the very western edge of the Old Town near the Funtime Arcade. No one knew what he’d been doing in that part of town, or had any idea what had happened to him. Cait suggested that he had wandered off and perhaps been hit by a car. ‘That happens to elderly people with dementia,’ she had said. But Griffin didn’t have dementia.

He was taken to a small hospital not far away. The next day, and the one after that, Effie had visited him instead of going to school. Each day he asked her to bring him something else from his rooms. One day it was the thin brown stick she had seen him putting in the secret drawer (which he now called a ‘wonde’, spelling it out so Effie realised it was a word she had never heard before); another day it was the clear crystal. She also had to bring him paper and ink, his spectacles and his letter opener with the bone handle.

On Saturday, Effie had found him sitting up and writing something, or at least trying to. Nurse Underwood, who was the mother of Maximilian, one of Effie’s classmates, kept getting in the way, checking Griffin’s pulse and blood pressure and writing numbers on a clipboard at the end of the bed. Griffin was so weak that he could only manage a word every few minutes. He kept coughing, wheezing and wincing with pain whenever he moved.

‘This is an M-codicil,’ he said weakly to Effie. ‘It is for you. I need to finish it, and then . . . You must give it to Pelham Longfellow. He is my solicitor. You will find him, you will find him, in . . .’ Poor Griffin was gasping for breath. ‘It is very important . . .’ He coughed quite a lot. ‘I have lost my power, Euphemia. I have lost everything, because . . . Rescue the library, if you can. All my books are yours. All my things. The wonde. The crystal. Anything that remains after . . . It says so in my will. I didn’t mean this to happen now. And find Dra . . .’

The door opened and Orwell came in and asked his father-in-law how he was.

‘We’d better go,’ Orwell said to his daughter, after a few minutes. ‘The greyout’s going to start soon.’

Every week there were a number of ‘greyouts’ when people were forbidden to use electricity. There were also whole weeks when the creaky old phone network was switched off entirely, to give it a chance to rest. This was why most people now had pagers, which worked with radio waves.

‘OK, just . . .’ began Effie. ‘Hang on.’

Orwell walked over and patted Griffin awkwardly on the shoulder.

‘Good luck with the op tomorrow,’ he said. And then to his daughter, ‘I’ll wait for you outside. You have three minutes.’

Effie looked at her grandfather, knowing he had been trying to tell her something important. She willed him to try again.

‘Ro . . . Rollo,’ said Griffin, once Orwell had left. There was a long pause, during which he seemed to summon all his strength. He pulled Effie close to him, so only she could hear what he said next.

‘Find Dragon’s Green,’ he said, in a low whisper. Then he said it again in Rosian. Well, sort of. Parfen Druic – the green of the dragon. What did this mean?

‘Do not go without the ring,’ said Griffin. He looked down at his trembling hands. On his little finger was a silver ring that Effie had never seen before. ‘I got this for you, Euphemia,’ said Griffin, ‘when I realised that you were a true . . . a true . . .’ He coughed so much the word was lost. ‘I would give it to you now, but I am going to use it and all the other boons I have to try to . . . to try to . . .’ More coughing. ‘Oh dear. This is useless. The codicil . . . Pelham Longfellow will explain. Trust Longfellow. And get as many boons as you can.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Effie, starting to cry. ‘Don’t leave me.’

‘Do not let the Diberi win, Euphemia, however hard it gets. You have the potential, more, even, than I ever did . . . I should have explained everything when I could, but I thought you were too young, and I’d made a promise, and the stupid Guild made sure that . . . Look after my books. I left them all to you. The rest of my things don’t matter much. Save only the things you brought to me here, and the books. Find Dra . . . Oh dear. The magic is too strong. It’s still preventing me from . . .’

‘What magic? What do you mean?’

But all her grandfather could do for a whole minute was cough and groan.

‘I’m not coming back, dear child, not this time. But I’m sure we will meet again. The last thing you have to remember . . .’ said Griffin, finally, again dropping his voice to a whisper. ‘The answer,’ he said, after a long pause, ‘is heat.’

When Effie woke up on Monday morning she had the feeling something terrible had happened. Her father had contacted the hospital late the night before and had then gone there in his car. Effie had begged to go with him, but he had told her to stay at home and wait for news there. No news had come. And to make a bad day even worse, Effie’s step-mother Cait had got up at five o’clock in the morning and, before doing her exercise video, had thrown every edible piece of food in the house into the outside bin. Not even in the kitchen bin – ‘We might be tempted,’ Cait had said darkly, to Luna, the baby, who was not old enough to say anything back – but the actual outside bin.

Everything was gone. All the bread, oats and cereals. All the jam. The sausages. The eggs. All the cheese. The last of the marmalade that Miss Dora Wright (Effie’s old teacher whom Effie had even been allowed to call Dora out of school, and who, before she disappeared, had lived in the apartment beneath Griffin’s in the Old Rectory) had made for them at Christmas. There were no crisps or chocolate – not that you would eat crisps or chocolate for breakfast unless you were really desperate, of course. Nothing.

Cait Ransom-Bookend (she had kept some of her old name when she’d married Effie’s father) read a lot of diet books. She read these books because she wanted to be as thin and beautiful as people on television, even though her actual job was researching a medieval manuscript that no one had ever heard of. The latest diet book was called The Time Is NOW! and told you how you could live on special milkshakes that had no milk in them. These were called ‘Shake Your Stuff’ and came through the post in huge fluorescent tubs. Each tub came with a free book sellotaped to it, usually a romance novel with a picture on the front of a woman tied to a tree or a chair or a railway line. Cait read a lot of these books lately too.

It seemed that something in The Time Is NOW! (which had a chapter called ‘Don’t Let Fat Kids Ruin Your New Look’) had made Cait choose today of all days to throw out all the nice food – food that might make you feel better if you were feeling a bit sad and worried – and present Effie, who usually made her own breakfast anyway, with a glass of greeny, browny gooey liquid that looked like mud with bits of grass stirred in it. Or, worse, something that might come out of you if you had gastric flu. This, apparently, was the ‘Morning Shake’. It was vile. Not that Effie was that hungry anyway. She was too worried to be hungry.

Baby Luna had her own shake that was bright pink. She didn’t look that enthusiastic about it either. A pink streak on the wall opposite her high chair suggested that she had already thrown it across the room at least once.

‘Looks awesome, right?’ said Cait.

‘Uh . . .’ began Effie. ‘Thanks. Any news from Dad?’

Cait made a sad face that wasn’t really sad. ‘He’s still at the hospital.’

‘Can I go?’

Cait shook her head. ‘The school rang. You missed two whole days last week, apparently. Your father and I talked about this yesterday. You’re not going to help your grandfather by . . .’

‘Has something happened?’

Cait paused just long enough that Effie knew that something had happened.

‘Your father . . .’ she began. ‘He’ll talk to you after school.’

‘Please, Cait, can you drive me to the hospital now?’

‘Sorry, Effie, I can’t . . . Your father . . . Effie? Where are you going?’

But Effie had already left the kitchen. She walked along the thin, dusty hallway to the bedroom she shared with Luna.

‘Effie?’ Cait called after her, but Effie didn’t respond. ‘Effie? Come back and finish your shake!’ But Effie did not go back and finish her shake. She put on her green and grey school uniform as quickly as possible, buttoned up her bottle-green felt cape, and left the house without even saying goodbye. She could go to school after she’d seen her grandfather.

Effie took the same bus as usual to the Writers’ Monument and walked up the hill to the Old Town, just as if she were going to school, through the cobbled streets, past the Funtime Arcade, the Writers’ Museum, Leonard Levar’s Antiquarian Bookshop and Madame Valentin’s Exotic Pet Emporium until, after cutting though the university gardens, she turned right instead of left and walked down the long road towards the hospital, hoping that no one would notice her uniform and ask where she thought she was going.

Effie had looked up the word ‘codicil’ in her dictionary the night before. It meant ‘a supplement to a will’. She’d had to use her dictionary several more times to work out what this might mean – there was of course no internet to help any more. A lot of people still had out-of-date dictionaries on their old phones, but Effie had a proper dictionary that Griffin had given her for her last birthday. All dictionaries – except for the very new ones – had a lot of old-fashioned words in them, like ‘blog’ and ‘wi-fi’. Things that only existed before the worldquake.

Eventually Effie had found that a codicil was something you could add to a will to change it in some way, and that a will was a legal document that said who got what after someone died. Then she remembered the play they’d read with Mrs Beathag Hide a few weeks before, where an old king kept changing his will on the basis of who he thought loved him most.

But why would Griffin be changing his will now? Was he going to die? Effie couldn’t stop thinking back to him lying there weak and alone in his hospital bed, his long beard looking so fragile and wrong resting on the crisp white sheets. Effie saw him trying desperately to write the codicil, dipping his fountain pen in the bottle of blue ink that made Nurse Underwood tut every time she saw it. On the hospital table was a pile of Griffin’s special stationery that Effie had got from his desk: cream paper and envelopes that looked expensive, but ordinary, until you held them up to the light. If you did this, you would see a delicate watermark in the shape of a large house with a locked gate in front of it. This watermark was on all Griffin Truelove’s stationery.

Effie had never been into her grandfather’s rooms on her own before last week. She hadn’t liked it at all. Everything sounded wrong, smelled wrong – and she kept jumping every time she heard an unfamiliar noise. The heating was switched off and so the place was deathly cold. Effie kept picturing her grandfather in that alleyway, wondering what had made him go there in the middle of the night. People at the hospital said he must have been beaten up by thugs, or just randomly attacked by ‘kids’. But Effie was a kid and she didn’t know anyone who would be likely to attack someone like her grandfather.

And what about his magic?

Because surely that’s when you would use magic? However difficult or boring you pretended it was, and however many lectures you gave on using magic responsibly, or trying all other methods of achieving something first, surely, surely, if someone was attacking you, almost killing you, that’s when you would . . .

What? Turn them into a frog? Shrink them? Make yourself invisible?

Effie realised miserably that after all this time studying with her grandfather, she didn’t even know what magic did. All she knew were lots of things it didn’t do. ‘Don’t expect magic to make you rich or famous,’ for example. Or, ‘Magic is not how you will get your true power, especially not in your case.’ But whatever it could do, her grandfather had not done it when he was attacked. It didn’t make any sense to her.

Of course, the obvious explanation was that magic didn’t really exist. After all, that was what most people in the world seemed to think, despite all the Laurel Wilde books they seemed to read. Orwell Bookend had always said that magic didn’t exist. But then last Wednesday he’d said it was dangerous, and implied that he almost believed in it. What had that meant? Effie wondered yet again how something that didn’t exist could have taken away her mother. How could something imaginary be dangerous? And, furthermore, if magic was so dangerous, why had Griffin not used it on the night he was attacked?