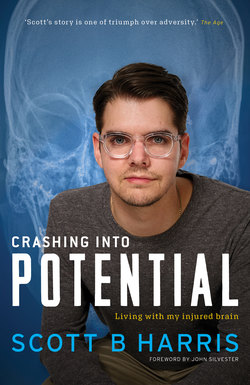

Читать книгу Crashing Into Potential - Scott B Harris - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеScott Harris’ world changed forever as he gunned his powerful trail bike while hugging the left side of a hilly track on a private property at Christmas Hills, northeast of Melbourne. Blindsided by the peak and deafened by the noise of his 450cc KTM bike, he had no idea his mate was heading towards him literally, as it would turn out, at breakneck speed.

Decisions we make in a blink of an eye can change our lives. November 15, 2008, was such a moment for Scott, then aged just 23.

He took the brunt of the oncoming bike head on, suffering catastrophic, near fatal and life altering injuries. Scott was flown to the Royal Melbourne Hospital, and no one was sure in those first few days if he would survive. His face had detached from his skull as all the bones were smashed, leaving him close to unrecognisable, even to his mother. Later plastic surgeons would insert ten metal plates in his cheeks, jaw and skull.

The first piece of good news was that while his neck was broken in two places, the spinal cord was intact. And when the odds started to swing in his favour, his parents, Victor and Debra, were told that while his body could be somewhat repaired, no one knew what would be left of their vibrant young son’s mind.

For sixteen days he was in a coma, and when he regained consciousness had post-traumatic amnesia – a sort of twilight zone where the patient has no short-term memory. To place it in perspective, a footballer who suffers a severe concussion may be in that state for a few hours. Scott was there for forty days.

Finally, he started to show positive signs. He had to re-learn how to talk, walk, eat and swallow, and undergo a series of operations replacing nerves destroyed in his neck, shoulder, arm and hand. In effect, the apprentice electrician was rewired.

At first, his rehabilitation was remarkable as he regained his balance, motor skills and some independence. Then he hit a plateau. As the recovery slowed his frustration increased, leaving him battling depression.

As a teenager he was a top white-water kayaker. He played footy, soccer, hockey, went skateboarding, wakeboarding, snowboarding and enjoyed water-skiing. At sport he wanted to excel but would lose interest if he were not the best. Now, facing his greatest challenge, he knew quitting was not an option.

His journey recorded in this book is one of courage, recovery and self-discovery, but more than that it is one of character. To write this book Scott had to turn himself into a detective to fill in the blanks from his long days in the twilight zone following his crash. Scott always tried to push boundaries; on the water or snow he was the one who would try the most outlandish trick. Post accident he continues to push the boundaries, this time against his injured brain, retraining his mind, travelling the world, returning to snowboarding and playing one-armed golf.

The Scott who has come out the other side is a different person. Before the accident, life revolved around parties, sport, friends, romance and his apprenticeship. Now he is deeper, determined to tell his story to help others overcome their own life challenges. His very character has changed. How much is due to the brain injury and how much to his frustrating, determined and rewarding journey from an intensive care bed to independence no one knows.

Once he dwelled on what he couldn’t do. Now he rejoices in what he can. A lesson for us all, perhaps.

He knows some of his dreams now can never be fulfilled, but he has new ones. Scott has become an accomplished public speaker and has spent time in schools and universities sharing his story of living with an injured brain. According to Royal Melbourne Hospital’s head of neurology, Professor Andrew Kaye, this is precisely the group that needs to listen, as the majority of brain trauma victims are males aged eighteen to twenty-five.

Specialists are amazed at how far Scott has come, although the journey is far from over. He could have disappeared into a world of depression; instead he chose to fight and learn to cope with what is a lifelong condition.

He was lucky – when he was clinging to life, the air ambulance was available and he received the best surgical and rehabilitation treatment available. In the end it was down to him. He had the guts to battle back and prove his injuries have not left him a lesser person.

The Harris clan is loud, self-opinionated, generous and gregarious. They love to talk – preferably at the same time. I should know. I married one of them – Victor’s sister. Scott Harris is my nephew. And I’m proud to know him.

This is Scott’s story and in these pages there are lessons for us all.

JOHN SILVESTER