Читать книгу Crashing Into Potential - Scott B Harris - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

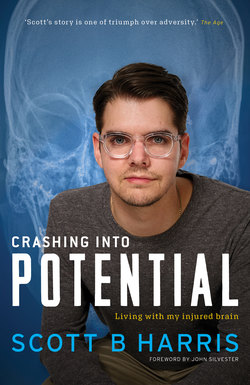

The Accident

ОглавлениеShit happens.

- HARRIS FAMILY

I had a great childhood. Some would say I was an active kid; I spent a lot of time outside running around. Any sport I played, I loved, until I wasn’t the best and then I would quit.

At one point I was kayaking, which I really enjoyed because this was something I was good at. My brother, Brett, and I would be up at 6 am in the middle of winter, out on the river paddling. We both loved it.

When I went to the Australian Championships, I won one gold, two silver and a bronze medal. After that I took six months off due to injury and bad health. When I came back to the sport I was no longer winning. This was the late 1990s and by the naughties, I had given up. I had quit because I wasn’t the best anymore. Now some of the guys who paddled with me then have competed in the Olympics.

It’s easy to look back on your life and think, What if? This question has crossed my mind so many times in the last decade and I have spent hours thinking about it. The conclusion I always come to is that I can’t do anything about it, so just move on. I can’t change the past, so I must move on.

I got my first job when I was fifteen, flipping burgers and making coffee at the local McDonald’s. In my opinion, this was the best job around because not only did I get to work with 120 other kids my age, I also made some lifelong friends. OK, granted, the work was hot and greasy and I hated getting up at 4.30 am when I had to set up in the morning. But it taught me what real work was and that in itself looks unbelievable on a résumé.

After five years, it was time to move on. But when I finished my tertiary education, I was jobless and I had no direction. I had done an Advanced Diploma in Digital Graphics at JMC Academy in Melbourne. My big dream was to work at the marvellous Pixar Studios in California. I could imagine being a part of the next big Toy Storyflick. That was until I discovered this was a dream shared by literally thousands and thousands of other people. With a ‘fixed’ mindset, I believed that the competition was too great, so gave up. I lost interest.

Being lost, I was starting to wonder where my life was going to go from here.

I found a job working at a cafe serving ice cream at Melbourne’s Federation Square, but when winter came around I had no real income because winter in Melbourne is cold, miserable and no one is on the search for ice cream.

After six months I was jobless again until my brother came to the rescue. He is an electrician and his boss was on holidays. They were in need of hands and any hands would do, so I put one up and helped out.

I fell in love with it. I worked for three weeks and earned more money than I had ever seen in one paycheck. So when the boss returned, I asked him if I could do an apprenticeship.

I started working full-time all over Melbourne: from high-rises to industrial estates to private homes. We worked in many of the manholes on the side of the road, connecting fibre networks across the city of Melbourne, sometimes Sydney and even Perth. We did a lot of work in new and old buildings, including old schools from the 1860s. You can imagine how fascinated a young man like myself was climbing through roofs and under buildings that were over 150 years old.

My job was so diverse that I could be working in an old building on Monday, building a new factory on Tuesday, and then every Wednesday I’d head off to trade school with an awesome group of boys. We would put our feet up and have some fun. Our classroom was jam packed with young men all full of testosterone having a day off work together; it wasn’t all that productive but I loved it.

Thursday we’d be under the city working and Friday we’d knock off early. Knocking off required going back to the factory in Eltham and having a beer to recap the week. My life consisted of no responsibility, no worries and all the freedom in the world. At the time, I liked the idea of working for ‘the man’ and not taking life too seriously. Oh, did I mention the RDOs? Yes, every second Monday we got a rostered day off, just because it was fair; that is what the trade union argued, anyway.

This was in 2006 and by 2008 I was loving what I did every day of the week. I loved my work because I made some great mates, I made some great money and I had the weekend to do what I wanted. At that stage, I started to think a bit about what would happen after I finished my apprenticeship, which was the first grown-up thought of my life. I considered travelling overseas and working abroad for a year, as my sister had done years before.

It was coming up to the Spring Racing Carnival – Melbourne’s premier horseracing event – which I had attended for the past two years. That year I went along with a great group of people. We had been mates for years and I had the best time I had ever had at the carnival. I remember that day so clearly.

I got up super early, just as I had on the first day of the carnival in the past. I woke up before my alarm and felt great from the early night I’d had to prepare myself. If the day turned out to be anything like the previous years, it was going to be a big event. I jumped out of the shower as quick as I had jumped in. Grabbing my race attire, I got in the car ready to go, all in the space of about ten minutes. I had a tendency to get overexcited about things I knew would be fun; that’s just who I was.

I was the first to arrive at my brother’s house and he had a beer waiting for me. Brett was already dressed in his suit and was just as excited as I was. I changed into my costume, a perfectly tailored grey suit from Thailand. I put on my new Prada sunglasses and a few sprays of cologne, looked in the mirror and quietly thought, it’s going to be a good day; you’re looking OK today, mate. I went out to the kitchen and said to everyone, ‘Let the games begin.’

While I’d been self-obsessing in the mirror, Ange and Celeste had arrived to join the party. Shortly after, Dave, Chris, Trav, Oki and Kate walked in and really got the ball rolling. It was about 7.30 am at this stage, which was rather early to be starting the antics, but to get a good spot on the grass, smack-bang in the middle of the riffraff, you had to be early. On top of that we still had to find a cab and make our way there. Really, the reason we started so early was because we all knew what was in store for us that day. And this was the first time in three years I was going there as a single man, with no one looking over my shoulder and no one to answer to. I was prepared to get loose.

Beep, beep, ‘Everyone, the cabs are here,’ was the call to head off to Flemington Racecourse. We got there just after the gates opened and made our way to the 300-metre mark at the end of General Admission on the home straight. The grass looked so fresh and the people looked so clean, but you knew that in just six hours time the bomb would go off and everyone would leave the venue looking like there’d been a meltdown. It did every other year – what would have changed? Nothing. To our delighted surprise, solid tables had been installed on the grass that year and we were lucky enough to snag one and enough chairs. It was still a few hours until the first race, but we didn’t really care because we were there in our position, ready to take on the day.

Once the bar had opened, things became very blurry in my mind as to what actually followed. My only memories of that day were the photos that were taken and the fact that I knew I had fun, I knew I was with my friends, and I knew that my wallet was crying due to weight loss. I was hoping for another box trifecta like I’d won the previous year. In my total gambling career I was definitely up, as I had won $1000 the year before and I’d never spent that much on gambling in my life. I really wasn’t a big gambler; the Spring Carnival was the only time that my wallet came out to gamble. I knew that it was dead money as soon as it touched the bookie’s hand. On top of the gambling, which wasn’t all that much in the end, there was the cost of drinks that seemed to go up and up and up each year. I guess that’s just the price you pay when participating in one of Melbourne’s great festivals.

In what seemed like less than a microsecond, I was in a hospital bed, a month later, looking up at Jaclyn, who was my brother’s girlfriend at the time, who was playing ‘Here comes the aeroplane’ with a spoonful of slop. Confused? So was I.

A couple of weeks after the Spring Carnival Derby Day, I had a motorbike accident that resulted in the worst day of my life. This was the absolute hardest time for everyone in my family too. They are forever haunted by the sixteen days I was in a coma, unsure whether I would wake up, let alone be able to live a normal life again. For my part, I was not consciously present and had no memory of it at all.

I was with my mates on Saturday, 15 November 2008, riding my dirt bike on a property in Smiths Gully in Melbourne’s outer northeast. It was at the very end of the day when I decided to go down for one last lap of the paddock before heading back to the house. I was going to meet another group of mates there for some springtime fun in the sun around the pool.

I got to the end of the paddock, turned around and rode back up the hill. It was not a tricky hill at all, but it had a little bend in the track before opening up to a landing about 100 metres long. I was going fast. If you’ve ever ridden a motorbike you will know the rush I would have been feeling at the time. The best way to start that hill was to give it full throttle and keep it pinned all the way to the top, because the top was my best chance to pop onto the back wheel and nearly wet my pants with excitement.

We had touched on the idea of riding down another track on that hill to avoid having an accident, but this wasn’t a rule and it wasn’t set in stone. I chose the one with the bend. I was in the wrong place at the wrong time on the wrong day of my life. I ran right into my mate who was riding down the same track at the same second that I was. Boom. Lights out. Hindsight’s a bitch when it wants to be.

The carnage looked like two angry wildebeests had fought in the wild, except our wildebeest were two KTM 450cc dirt bikes. Another mate was following behind me and saw everything happen. He said it was like watching a finishing move in Mortal Kombat in slow motion. He could see what was happening but was helpless to stop it. We hit each other head-on and when I say ‘head-on’, I mean ‘HEAD-ON’. Our front wheels were aligned perfectly and you could see the imprint of his wheel in mine. The mate following threw his bike down and ran to help.

He knew that both of us were in serious trouble. He was shouting in my face, ‘SCOTT, SCOTT, SCOTT...’ No response. He ran over to our mate and did the same thing, like a sequel to a horror movie. Neither of us was responsive. Another two mates, brothers who lived at the property, finally caught up with us. The first guy to arrive felt his heart sink because for a split second he thought it was his own brother who was in trouble on the ground and not moving.

From the time of the accident until the air ambulance flew me away, everything ran like clockwork. One mate, Dave, rode off straight to the house to ring 000, his brother, Ryan, rode to the front gate and our other mate stayed with the two of us to make sure we were still breathing. There were five of us riding that day, and two of our lives depended on the teamwork of the other three. I am so grateful that I had the mates I had with me, and I am really proud of the teamwork that they put in that day.

Sam, the mate I hit, stood up at one point, took one step and then hit the deck. He was extremely lucky because, unknown to anyone, he had broken his neck. A few more steps could have left him bound to a wheelchair for the rest of his existence on earth. I, contrary to popular belief, was the luckiest at the time because I was knocked out cold and didn’t budge. With the state my neck was in, any slight movement could have left me writing this book through a voice-activated dictaphone.

The ambulance arrived within fifteen minutes, only to find that there was no way to drive down through the goat tracks from where they were to the other end of the property. Right then another star moved into alignment. Out of four air ambulance helicopters that operate in the whole state of Victoria, the two that were close enough were told to turn around and come to our aid. This was perfect because time was definitely not on our side. It took them only twenty minutes to get there, which, if you think about it, is amazing because there are only four helicopters covering 237,629 square kilometres of land in Victoria. To put that into perspective, that’s nearly England, Ireland and Switzerland combined.

Once they had landed, it was time to remove my helmet, which was the only thing holding my skull together and stopping it from exploding. I still have that helmet, with a coating of crusty blood on the inside. It’s a token from God on a day in history that could easily have resulted in many lives destroyed.

There were many, many people that saved my life that day. Four paramedics, four police, many doctors, many nurses, dental surgeons, neurosurgeons, neurologists, radiologists, a whole plastics team; the list goes on. But the guys that I truly owe my life to on that dark but sunny, spring day are my mates. The three boys that were there with Sam and me came together and put in some pretty amazing teamwork, and for that I am truly grateful.

The accident wasn’t just brutal on me; Sam had intense damage to his body too. His injuries included several fractured vertebrae and bones, a punctured lung, lacerations and a dislocated knee. He experienced severe blood loss, resulting in seven blood transfusions. Sam has also been recovering both mentally and physically from this accident and has since changed his career path. This accident made him realise how vulnerable and fragile life is and he no longer wanted to waste his time doing anything that didn’t make him happy. He decided his passion was flying aircraft so he got his pilot’s licence and now flies planes for a living. How cool’s that?