Читать книгу Sew-It-Yourself Home Accessories - Scott Wynn - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

You may ask yourself: Why bother?

I mean, when we have so many other beautiful planes to choose from that could certainly do the job well enough? Planes we are probably more familiar with, marvelously mechanical metal planes of proven reliability. And other styles of planes as well, both beautiful and functional.

Well, simply put, if you’ve got a lot of work to do in solid hardwood, the traditional wood plane excels at efficiently working hardwoods and is better at this than any other style of plane.

Say you have a large plank, maybe a live edge board for a tabletop, and it’s too big to fit in your jointer. The traditional jack plane—maybe preceded by a scrub plane, used with the correct technique—is light, low in friction, comfortable in the hands, and will quickly take the high spots off, leveling one face of the board sufficiently to get good registration through the planer. Or maybe your planer isn’t big enough either. Traditional wood handplanes, used in the traditional sequence, with the blades correctly shaped and with appropriate blade angles, will make this job doable.

Or say you have a nice piece of figured hardwood that just wants to tear up when you go to work it. Only with a high-end two-drum sander will you get results that won’t take hours of sanding to get rid of the ripples, variations at changes in hardness, and streaking that the nonindustrial sanders tend to leave. Again, use of traditional wood handplanes, used in sequence with the correct blade shapes and angles—angles that you can’t find on most planes—will yield crisp, smooth results at a rate competitive with sanding—and without the dust and noise and vibration and sheet after sheet of sandpaper.

After over 40 years using handplanes, many times for hours at a stretch, days at a time, with every style of plane and in every type of wood, I have developed some criteria for planes for doing serious work on hardwood (I’m talking serious work here—not the occasional edge or snipe removal). You can of course challenge these if you wish, but it will give you something to think about—and maybe you can add a few criteria to your own list.

The criteria

Weight is an important consideration: you will be lifting these planes a lot during the day, maybe several hundred times. How often can you curl an 8-pound dumbbell (the weight of a premium #7 Bailey-type plane)? So, the planes should be comparatively light, though a balance between weight and inertia is often desirable.

The sole of the plane should be low in friction; like weight, the cumulative resistance adds up and it is palpably noticeable. It also interferes with feedback with how the plane is cutting.

You need blade angles other than just 45°. I have found that oak works tearout-free with a blade angle of 60° to 65°; walnut likes blade angles of 50° to 55° to finish. So the ideal plane should be available, or be able to be made, in a range of blade pitches; 40° to 65° is ideal, though 45° to 55° will suffice. This is for both reduced resistance when removing large amounts of stock (the low end of the scale) as well as the ability to reduce tearout for fine finishing (the high end of the scale).

Planes should be available in a variety of widths, with blades from 1 ¼" to 2¾" (3.2cm to 7cm) wide; this is because different planes do different tasks and require different width blades (much more on this in the succeeding chapters). In the same vein, you should be able to fit a variety of commonly available blades of different steels because different tasks and even different woods are done more effectively if the steel is matched to the work.

The grip of the plane must not be fatiguing, blistering, or bruising to the hands even after hours of pushing and must successfully transfer all the energy put into it to the cutting action. I have found that the larger the area of the hand the grip engages, the easier it is on the hand.

And, ideally, they should be affordable!

So how do the other styles of planes stack up when measured by these criteria? Let’s start with the Stanley Bailey style plane. If you have a lot of work to do you’ll soon realize these planes are heavier than their wooden cousins: often quite a bit. A traditional Razee-style wooden fore plane, for instance (of which plans and instructions for making are included in this book), is about 4 pounds, while the classic iron Stanley version is a smidgeon over 6 pounds. The premium version of the Bailey plane comes in at 7 ½ pounds (3.4kg)—nearly twice as heavy as its wooden counterpart! Arguments that planes of greater weight are needed to provide increased momentum to power through hardwoods (it’s not needed) have a flip side; they also require greater effort to overcome the inertia of getting the plane moving. Meanwhile you’re lifting twice the weight on every stroke of the plane. (Proper technique says you don’t drag the plane on the return stroke; this adds wear to the blade, though you will see a lot of well-known woodworkers do it. The plane should be lifted or slightly tilted on its side or front edge to reduce wear on the blade.)

The metal sole has a noticeably higher coefficient of friction with a noticeably higher resistance to the push. You can lubricate the sole but most lubricants, such as wax, wear off in a half dozen strokes and must be repeatedly reapplied.

The blade, with the exception of a couple of expensive high-end versions, is always bedded at 45°, which works ok for a number of woods, but not so good with a lot of common hardwoods; having blade angles that match the type of work to be done, and the type of wood to be planed, can save you a lot of time, effort, and frustration. Blade-width selection, however, is good, as is the variety of blade steels now available, allowing you to customize the type of steel to the kind or work and wood you want to do.

I do have a problem with the handles, however. I find they soon blister my hands. They’re too narrow, focusing the strain on narrow portions of the hand, and they’re often curved and/or angled wrong. I have a vintage #8 and a vintage #6, both with beautiful rosewood handles; the handle on the #6 fatigues while the other does not. They look the same; any difference is almost imperceptible. Others may not have experienced this, but I think if you’re doing significant work with these planes, eventually you will. The ball front knob is too small for doing a lot of work and concentrates the pressure on the center of the hand, which soon blisters, aided and abetted by the screw head in the center of it. The rear handle often allows the hand to slide down to its base and is angled and shaped such that the heel of the hand will start to get badly worn (and sometimes the side of the little finger). Between the weight, the friction, and the blistering handles, these planes are not made for extensive work. They can sit on the shelf for weeks at a time and be used off and on without readjustment or maintenance and they’re great for most of the tasks you’ll find around the wood shop, but they are just not the best choice for heavy work.

The Krenov-style plane, light, made of low friction wood, is a delightful smoother, but I don’t think it’s as versatile a style for all the jobs you might want to use a plane for. Because of the low position of the hand on the plane when making deep cuts to remove stock (as you might with a jack plane), the hand wants to slide forward against the blade. This takes its toll pretty quickly. Also, the selection of blades for this style of plane is limited. Those who favor Krenov-style planes might want to supplement their arsenal of planes with a traditional style jack, and maybe a jointer and scrub, depending on the type and size of work you do.

The Japanese-style plane is light, low friction, comes with some of the best blades you can get, and performs pretty well through most tasks, including stock removal—except when you have to remove a lot of stock in a hard wood. Surprisingly, despite no outward accommodation to the hand, they are not blistering, or even particularly fatiguing. But as a pull-plane, you do have to hold on to it; with a push-plane, if the grips are right, the plane is cradled in large parts of the hands so if you didn’t have to lift it to bring it back very little effort would be expended holding on to it. Additionally, with a push-plane it’s easier to get your body weight down and behind the push; this is more difficult when pulling a plane.

And finally, there is the issue of affordability. The traditional wood plane beats the competition here as you can often find usable vintage planes for a fraction of the cost of even a vintage Bailey—and often at one-tenth the cost of a new premium Bailey. A lot of these planes were made and a lot of them are still out there, and so far non-collectible user planes are still quite affordable. And you can get something on these planes that you can’t get on a new plane: a hand-forged laminated blade—often the best choice for smoothing (more on this later). While newly manufactured versions of the traditional wood plane may be as costly as a decent Bailey plane, they maintain the advantages of lower weight, low friction, good ergonomics while often having improved adjustment mechanisms, and the advantage over a vintage wood plane of not having to invest time to repair them before you can use them.

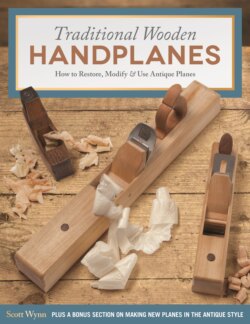

This book is about the traditional wood planes used predominantly in Europe and North America, both vintage and contemporary, and also will touch on the planes of China and Southeast Asia and how they might be useful. It will show you how all these traditional wood planes work, how to set up a flea-market find, as well as how to tune up a new plane to get the best performance out of it. It will talk about the different types and how to use them to their best advantage; which blade angles are best, which blade steel you might want to use, and finally, how to make your own set of planes using some modern techniques that simplify construction and improve performance.