Читать книгу Emmet Dalton - Sean Boyne - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

My fascination with the story of Emmet Dalton goes back to my boyhood in 1950s Dublin. It was a drab, grey era, and it seemed to me that Dalton brought a touch of glamour and much-needed excitement to the austere Irish scene by founding Ardmore film studios near Bray, County Wicklow. My parents were great newspaper readers, we were also great cinema-goers, and I read exciting stories about Dalton’s Ardmore venture attracting well-known film stars like James Cagney to Ireland to make movies. Dalton’s own teenaged daughter, Audrey, had become a film star in Hollywood, and in the Irish media this was a great success story. It meant that ‘one of our own’ was appearing in films with some of the biggest names in the movie business.

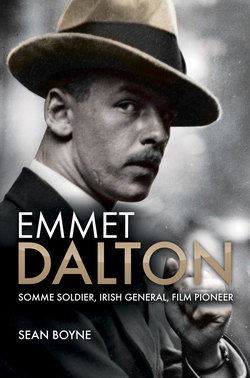

It emerged that Emmet Dalton was a man with an intriguing military past. Sometimes the newspapers referred to him deferentially as Major General Dalton. I cannot recall when I learned that he had won an award for bravery while serving as a junior officer with the British Army in the First World War. The 1950s was an era when official nationalist Ireland seemed reluctant to acknowledge the role of the countless thousands of Irishmen who had fought in British uniform ‘for the rights of small nations’ during that conflict. But I do remember being utterly spellbound reading an interview with Dalton about an exploit during the subsequent Anglo-Irish War when he had thrown in his lot with the IRA. He told how he had bluffed his way into Mountjoy Prison in a hi-jacked armoured car in a vain attempt to rescue a notable IRA leader. The article was accompanied by a large photograph of Dalton, a handsome man with a neatly-clipped, military-style moustache. I thought that something of his calm air of authority and his qualities of leadership came through in that picture.

When the Irish republican movement split on the issue of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Dalton stayed loyal to his friend, the charismatic pro-Treaty leader Michael Collins, known as the Big Fellow, whom he hero-worshipped. Collins, clearly impressed by Dalton’s raw courage and his military experience, had brought him to London as an adviser during the difficult Treaty talks with the British. Back in the 1950s I was unaware that Michael Collins had died in his arms in an ambush at a remote valley near a place called Bealnablath during the Irish Civil War.

I eventually discovered that Dalton had been a student of the Christian Brothers at O’Connell School in Dublin where I was educated myself. Two of the retired Brothers living at O’Connell’s during my era had known Dalton well, I would later discover – one was Brother William Allen. The ethos in the school was strongly nationalist and we were told much about Irish history, especially the 1916 rebellion and the depredations of the Black and Tans. A former teacher at the school, a quiet-spoken man called Joseph Tallon, was brought in by our teacher, An Bráthair Ó Flaitile, to tell us of his own role in the 1916 Rising. (Sadly, I can only remember one quote: ‘We had all been to Confession, and we were all prepared to die.’) So why were we not told about the exciting military adventures of this very distinguished past pupil, Emmet Dalton? I believe it was to do with the Irish Civil War – it was a taboo subject. This was understandable. When I first attended O’Connell’s, it was only thirty years after the end of the ‘brother against brother’ conflict. Despite some reconciliation that had taken place, memories were still strong and emotional wounds were still raw. Former school friends at O’Connell’s had fought on different sides and there was personal bitterness. I was astonished to learn that one of Dalton’s former schoolmates had put him on a ‘death list’ during the war, to be shot at sight. In my ten years at O’Connell’s, I don’t believe I heard the words ‘Irish Civil War’ mentioned even once. As a result, it was only in later years that I began to learn about the remarkable story of Emmet Dalton.

As I talked to people who knew him and delved into the archives, a picture of a rather complex man emerged. He was a tough-minded soldier who in times of war could be a relentless fighter and was capable of making very hard decisions; he wanted to protect his men and he wanted his side to win. He was endowed with physical and moral courage, and at least one person talked of the element of ‘steel’ in his character. He had fine human qualities – he could be sensitive, kind and compassionate, was loyal to comrades and friends, and wrote poetry. He also had a forceful personality, exuded a sense of authority, and had the calm, self-assured air of a natural leader of men. He had a low tolerance for what he regarded as nonsense or subterfuge, and had a reputation for being stubborn. On the other hand, he had great charm and was a pleasant, congenial companion; people liked to be in his company, he was a great raconteur and he was noted for his dry sense of humour. It has been said that old-fashioned patriotism was one of the motives behind his efforts to establish an Irish film industry.

He was a believing Catholic all his life and in his final years took much consolation from his faith. However, some in the church may not have entirely approved of his sideline as a semi-professional gambler, betting heavily on the horses. For a period as a young man he drank heavily, before showing his usual self-discipline by giving up alcohol totally. Apart from some early marital difficulties due to his ‘taking to the drink’, he had a very happy marriage, and was much loved by his children and grandchildren. He loved sport, played soccer in his youth, and was a gifted golfer.

In addition to his other accomplishments, Dalton was one of the founding fathers of the Irish Defence Forces. It could be argued that he was one of the first members of the Volunteer force, that evolved into the Irish Army, to use an armoured car in an operation – albeit an armoured car hi-jacked from the British, as outlined above. He played a key role in procuring the first aircraft and recruiting the first two pilots for the unit that would develop into the Irish Air Corps. He oversaw the takeover from the British of military bases, some of which are in use by our Defence Forces to this day, and played an important role in training and recruitment as the new National Army took shape. He procured the first field guns for that force, and commanded the first artillery bombardment at the start of the Civil War. When he led a daring seaborne invasion of the south coast, pushing the anti-Treaty forces out of their bases in Cork city and county, one of the ships he deployed was a vessel that would later form the basis of a future Irish naval service. It was the most significant amphibious operation of the Civil War, an Irish mini-version of the D-Day landings, and it played a crucial role in turning the tide of war against the republicans. When he accomplished all this the ‘boy general’ of the Free Staters was only twenty-four years old. The more I discovered about this past pupil of O’Connell’s the more interested I became. This biography is the result of that long-standing fascination with the life and times of Major General James Emmet Dalton (1898–1978).