Читать книгу Emmet Dalton - Sean Boyne - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The Great War

In the high summer of 1916, the Battle of the Somme was raging in France. This great Allied offensive against the German lines was set to become the bloodiest encounter ever experienced by the British Army in its long history. The fighting at the Somme had been in progress for a couple of weeks when, back in Ireland, on 15 July, 18-year-old Emmet Dalton passed his military examinations. He was judged to be an officer who was qualified for active service with the 7th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (RDF). The following month 2nd Lieutenant Dalton was sent to France. The scale of the carnage meant that the British war machine required a constant supply of young men like Dalton to be hurled into the maelstrom. Soon, the teenaged officer would find himself in the firing line in a major offensive. Having lied about his age on joining up, it appears he continued with the subterfuge. In the official booklet given to each officer, the Officer’s Record of Services, his date of birth is given as 4 March 1896, instead of 1898 – adding two years to his real age.1

In early September Dalton was transferred to the 9th Battalion, RDF, attached to the 48th Irish Brigade. The 48th brigade was part of the 16th (Irish) Division, commanded by Major General W.B. Hickie. Many of the officers and men in the Division were Redmondites, supporters of Home Rule. Like Dalton, there were those who had been shocked and horrified at the news of the Easter Rising in Dublin. The men of the Division were up against a formidable German foe who had already killed many of their comrades, and it seemed to some of them that the rebels back in Dublin had thrown in their lot with this enemy.

For a young man far from home in a dangerous, challenging environment, it can be very reassuring to encounter a familiar, friendly face. Dalton was delighted to meet, among the officers of the 9th, his father’s friend Tom Kettle. The former Irish Party MP had forsaken his post as Professor of National Economy for the rather more dangerous role of a company commander with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Noted for his eloquence and his scholarship, he had achieved considerable prominence in the Nationalist movement and was a co-founder of the Land League.

The 9th Battalion was about to take part in a major offensive to capture what remained of the town of Ginchy. In the few days they were to have together in the advance trenches before the Ginchy operation, Emmet Dalton and Tom Kettle became firm friends, despite the age gap between them. Kettle was 36 years old – twice Dalton’s age. Dalton found Kettle to be a ‘very charming and delightful man’. Dalton recalled sitting with him just before the movement up to the front line for the offensive. ‘He recited to me a poem that he had written to his daughter, and he had it written down in a field notebook.’ Dalton said it was a ‘delightful little poem’.2 To My Daughter Betty, The Gift of God would become one of the most memorable poems to emerge from the Great War.

Kettle could have avoided the assault on Ginchy in which he was to die but he chose to stay with his men. On the night before his battalion moved up to the Somme, Kettle wrote a letter to a friend saying that he had two chances of leaving – one on account of sickness and the other to take a staff appointment. ‘I have chosen to stay with my comrades,’ he wrote. ‘The bombardment, destruction and bloodshed are beyond all imagination. Nor did I ever think that valour of simple men could be quite as beautiful as that of my Dublin Fusiliers.’3 The extent of the bloodletting was brought home to Dalton in a chilling manner when he was walking along a trench. The ground seemed soft and soggy with what appeared to be stones here and there, and he kept slipping. He mentioned the stones underfoot to a sergeant who informed him that they were not stones – they were the remains of men killed in previous fighting.4

The Germans had a firm grip on Ginchy, and British commander Field Marshal Douglas Haig was determined that it would be captured. Previous attempts had been made to seize Ginchy by 7 Division, and they had come from the same direction, Delville Wood. The forces of 7 Division were withdrawn after suffering massive casualties. Now the British top brass decided to attack from another direction, from the south, throwing the 16th (Irish) Division into the fray. The Irish would attack from the newly-captured area around Guillemont. They would also mount an assault in greater strength than 7 Division. The weather was unfavourable – rain was falling. However, good fortune would favour the Irish, in that two new German divisions had been deployed in the sector and effective communications had not been established between them. As a result, the forces holding Ginchy lacked support.5 This lack of coordination helped give the Irish the edge as they advanced, supported by artillery. Nevertheless, the attacking forces would suffer very heavy casualties.

Death of Tom Kettle

Dalton later recalled how he and Tom Kettle were both in the trenches at Trones Wood, opposite Guillemont, on the morning of 8 September 1916.6 The mood was sombre. Their battalion had sustained heavy casualties from German shellfire the day before, losing about 200 men and seven officers. As they talked, an orderly arrived with a note for each officer: ‘Be in readiness. Battalion will take up A and B position in front of Guinchy [Ginchy] tonight at 12 midnight.’ Kettle was in command of B Company while Dalton was second-in-command of A Company.

Dalton recalled in a letter: ‘I was with Tom when he advanced to the position that night, and the stench of the dead that covered our road was so awful that we both used some foot-powder on our faces. When we reached our objective we dug ourselves in, and then, at five o’clock p.m. on the 9th, we attacked Guinchy’ [sic]’.7 It is unclear why the attack was timed for so late in the day. It may have been intended to deprive the enemy of sufficient daylight time to organize a counter-attack. It may also have been because the enemy expected a normal dawn offensive starting time.

The massed ranks of British artillery opened a rolling barrage as the Dubs left their trenches. Dalton recalled the moment that Kettle was hit.8

I was just behind Tom when we went over the top. He was in a bent position, and a bullet got over a steel waistcoat that he wore and entered his heart. Well, he only lasted about one minute, and he had my crucifix in his hands. Then Boyd9 took all the papers and things out of Tom’s pockets in order to keep them for Mrs. Kettle, but poor Boyd was blown to atoms in a few minutes. The Welsh Guards buried Mr. Kettle’s remains. Tom’s death has been a big blow to the regiment, and I am afraid that I could not put in words my feelings on the subject.

In another letter Dalton wrote: ‘Mr. Kettle died a grand and holy death — the death of a soldier and a true Christian.’10 It is said that when Kettle’s aged father Andrew heard the news that his son was missing in action, he responded: ‘If Tom is dead, I don’t want to live any longer.’ True to his word, within two weeks he himself joined his son in death, passing away at eighty-three years of age.

Although there was no trace of the personal possessions that Tom Kettle had with him when killed, happily the poem that he wrote a few days before the battle survived. Perhaps fearing that the end was near, Kettle had written To My Daughter Betty, The Gift of God for his young daughter Elizabeth, born on 31 January 1913. The final, poignant lines are still regularly quoted:

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for Flag, nor King, nor Emperor,

But for a dream, born in a herdsman’s shed,

And for the Secret Scripture of the poor.

Dalton’s daughter Audrey told the author that her father carried a copy of that poem in his wallet with him all his life, until the day he died.

The 8th and 9th battalions of the Dublin Fusiliers led the assault through Ginchy, their objective being the German support trench on the northern outskirts. The town, on a hill, had been well fortified by German engineers. It was defended by the 19th Bavarian Regiment, which had only recently arrived in the sector and was not fully familiar with the positions it was required to hold. About 200 of the German enemy surrendered, while others ran, pursued by the attackers. It was said that because of the loss of so many of their officers, the Irish soldiers, in hot pursuit of the enemy, carried on beyond the objective, and had to be brought back. Eventually the Irish consolidated their positions around the town.

Dalton’s 9th Battalion suffered heavy losses in the attack on Ginchy. Many of the officers were killed or wounded, and Dalton, one of the most junior of the officers, had to take command of two companies – or what was left of the companies. He deployed these as best he could and sent a runner with a message back to command HQ that they were now in control of Ginchy. The order came back that they were to hold their position. The capture of Ginchy gave the 16th Division a prominent salient in the German lines, and it was only a matter of time before the Germans mounted a counter-attack. Bavarian infantry came in on the offensive at 18:20 and 21:00 and met stiff Irish resistance.

As Dalton and his men came under heavy fire, he deployed machine gun teams in key locations to discourage the enemy, even managing to take prisoners after he came face-to-face with enemy forces after dark. Dalton and his men held out until relieved after twenty-four hours by a battalion of the Welsh Guards. Dalton and another officer, 2nd Lieutenant Nicholas Hurst, a noted rugby player from a Church of Ireland family in Bantry, County Cork, were the only officers of the 9th Dublins to walk out of the battle relatively unscathed. The rest were killed, wounded or missing.11 In the aftermath of the battle Dalton served as acting Captain.

For his actions on the day of Ginchy battle, Dalton was later awarded the Military Cross – his nickname afterwards would be ‘Ginchy’. The full citation reads:

At the capture of Guinchy [sic], on the 9th of September, 1916, he displayed great bravery and leadership in action. When, owing to the loss of officers, the men of two companies were left without leaders, he took command and led these companies to their final objective. After the withdrawal of another brigade and [while] the right flank of his battalion was in the rear, he carried out the protection of the flank, under intense fire, by the employment of machine-guns in selected commanding and successive positions. After dark, whilst going about supervising the consolidation of the position, he, with only one sergeant escorting, found himself confronted by a party of the enemy, consisting of one officer and twenty men. By his prompt determination the party were overawed and, after a few shots, threw up their arms and surrendered.

Many years later, Dalton would remember Ginchy as ‘sad … a glorious victory with terrific losses’.12 The 16th Division suffered very heavy casualties in the period 3 September to 9 September – 224 officers and 4,090 men killed or wounded.13

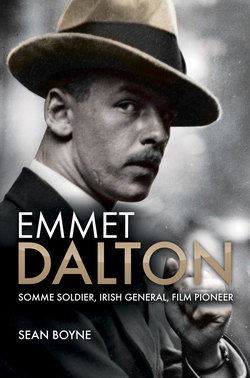

Dalton was wounded in the fighting and was to spend time in hospital in France. While Dalton’s father may have had misgivings about him joining the British Army in the first place, he seems to have had a considerable sense of pride about his son being injured heroically in the war against the Germans. A notice in the Irish Independent on 21 September 1916, that appeared to have been placed by the family, declared: ‘Lieut. Emmet Dalton, Dublins, wounded, is a son of Mr J.F. Dalton J.P., 8 Upper St. Columba’s road, and 2, Talbot St., Dublin.’ The notice was accompanied by a photograph of a youthful Dalton in military uniform, sporting a military-style moustache.

Dalton received treatment for his wounds at The Liverpool Merchants Hospital at Étaples, France. It was one of a number of military hospitals situated in a sprawling base camp near the old town and port of Étaples, which lies at the mouth of the River Canche, in the Pas de Calais region of Picardy. He was one of the officers to receive a letter from a distraught Mrs Mary Kettle seeking details about her husband’s death, and the possible location of his remains. On 14 October Dalton replied to Mrs Kettle, apologizing for the delay in answering the letter. ‘I presume by now that you are utterly disgusted with me for failing to reply to your letter, but I assure you that if I had been in a fit condition I would have replied before now.’ He described the last moments of Tom Kettle, clearly trying to be as sensitive and consoling as possible.

Although an articulate man, decades later, in his RTÉ interview with Cathal O’Shannon, Dalton would struggle to find the words to convey the horrors of the Battle of the Somme: ‘It would be very hard to describe the Somme – I don’t know if there has ever been a battle like it.’ The butcher’s bill for this long-running fight was enormous. It has been recorded that between 1 July and mid-November 1916, the British Army suffered a massive 432,000 casualties – an average of 3,600 for every day of the blood-soaked encounter.

Return to Dublin

Dalton, no doubt to the great relief of his family, was stationed in Dublin for a period following his treatment in hospital. His mother, in particular, fussed over him, sewing leather cuffs onto the sleeves of his uniform.14 By early 1917, Dalton was attached to the 4th Battalion, RDF as an instructor in a musketry course. This was located at Bull Island, off the north Dublin suburbs of Clontarf and Dollymount, which was commandeered by the British Army in 1914 for a military training ground. A School of Musketry was established there complete with rifle ranges and facilities to teach trench warfare tactics. The clubhouse of the Royal Dublin Golf Club was taken over as quarters for officers. Dalton had probably established a reputation as a marksman to be selected as an instructor for this particular course.

In March, Dalton worked as an instructor on another course in his home city – an anti-gas attack course at the Irish Command School, Dublin. Both sides in the war mounted gas attacks, inflicting heavy casualties, and causing much fear and trepidation among troops targeted by chemical weapons.

Awarding of Military Medal by King George

A few weeks after giving the anti-gas course, Dalton travelled to London to collect his award for bravery from the British crown. On 2 May 1917, at Buckingham Palace, King George V awarded a range of decorations to members of the British Army and Commonwealth forces, ranging from the Distinguished Service Cross to the Military Cross. Among the approximately seventy military personnel who received the Military Cross, there were just two from Irish regiments – Second Lieutenant Richard Marriott Watson, Royal Irish Rifles, and Second Lieutenant Emmet Dalton, of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.15 Dalton’s luck held out and he would, of course, survive the war. Marriott-Watson, a poet and only son of the Australian-born writer, Henry Brereton Marriott-Watson, was killed the following March during the retreat from St. Quentin.

Decades later, Dalton reminisced to an American friend about the day he was presented with the Military Cross. Even though he had opposed the Easter Rising, it appears that nationalist sentiment engendered by the Rising had been having an effect on Dalton. The execution of the leaders, and their bravery in facing death, had stirred up public sympathy. He privately told journalist Howard Taubman about his feelings during the ceremony held in the presence of the King at Buckingham Palace. According to Taubman, the protocol was that when the riband with the Military Cross was hung around his neck, Dalton was to bow from the waist down in deference to the King. Thinking about the Easter Rebellion the previous year, he decided not to make the obeisance, and stayed standing ramrod straight in defiance of the court etiquette The moment the last presentation had been made, Dalton bolted from the room and left the palace.16

Dalton was promoted from 2nd Lieutenant to Lieutenant on 1 July 1917, and just over a week later was deployed abroad to Salonika, where allied forces were engaged in hostilities with the Bulgarians. He was now with the 6th Battalion, Leinster Regiment, having been transferred from the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The Prince of Wales’ Leinster Regiment had its home depot at Crinkill Barracks, Birr, in the Irish midlands, and drew its recruits largely from counties such as Longford, Westmeath, Offaly (King’s County) and Laois (Queen’s County). The regiment had been in the thick of the fighting at Gallipoli.

Bulgaria, which occupied a strategic position in the region, had entered the war on the side of the Central Powers, attacking Serbia in October 1915. The 10th (Irish) Division was among the Allied formations deployed to the region. The 6th and 1st Battalions of the Leinster Regiment were located in the Struma Valley. During his service in Salonika, Lieutenant Dalton, like many other Irish soldiers, contracted malaria. While in a rest camp he encountered a Scotsman who had been a professional golfer. The Scot instilled in Dalton an interest in golf that would develop into a life-long passion.17 However, his first opportunity to test his skills on the green would come in an unlikely place, Egypt, a country not then noted for its golfing facilities.

War in the Middle East

In September 1917, the 10th (Irish) Division moved from Salonika to Egypt for service in the Middle East. The British top brass had decided that it was more urgent to confront the Turks in Palestine than the Bulgarians. It was on 14 September that men from the 6th Leinsters embarked on the steamer Huntsgreen. Five days later, after an uneventful voyage, they arrived at the ancient, bustling port of Alexandria. For Dalton and many of the Leinsters, this would be their first experience of the exotic world of Arabia. It would be an interesting period of service for Dalton, and he would learn about living under canvas in the desert and the rugged hills of the region, and the more mobile nature of the war in the Middle East.

On arrival at Alexandria, the 6th Leinsters boarded trains and travelled by way of Ismailia to Moascar where the battalion set up camp with other elements of the 10th Division. The battalion began a programme of desert route marches along with regular bathing in the salt water lakes of Ismailia which, it was hoped, would help cure the malaria that affected many of the men. Dalton would have first glimpsed the commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), General Allenby, when the latter came to inspect the camp, with the men of the battalion lining up outside their tents. Then they marched along the Suez Canal, finally reaching Kantara on 2 October, where Dalton and his comrades put their surplus kit in storage. Allenby had been developing and upgrading railway facilities through the Sinai to facilitate the movement of troops to areas close to the front line. Dalton’s battalion moved by train to Rafah, reaching it on 4 October. Training was carried out by the battalion. The water had to be piped from Kantara and was in short supply. Each man was limited strictly to three-quarters of a bottle a day ‘for all purposes’.18

Allenby’s forces moved into position and on 26 October the Third Battle of Gaza began, on the Gaza-Beersheba front. Dalton would not find himself in the front line at this stage – perhaps because of the malaria that infected many of the men, his battalion was assigned a logistics support role. The men of the 1st and 6th Leinsters were given an unglamorous but vital task – organizing camel convoys to carry water for the men and horses engaged in combat. Each camel carried two fifteen-gallon water tanks known as ‘fanatis’. After the capture of Beersheba, the Leinsters moved up to the town itself. The historian of the Leinster Regiment has left a vivid account of horses almost mad with thirst at Beersheba, and being dragged away by exhausted men after they had the ‘briefest drink’ at the troughs.19

The 6th Leinsters was placed in reserve behind a small hill, as Allenby’s forces continued the offensive on the Turkish positions. Some of the Leinsters had a bird’s eye view of the fighting from observation positions on the hill. When the Turks were forced to retreat, the Leinsters moved up to occupy the Turkish trenches. On 5 November the two Leinster battalions joined the advance on Jerusalem, some forty miles northeast of Beersheba. It was a campaign of movement and manoeuvre, much different from the more static trench warfare that Dalton had experienced on the Western Front. They marched through hill country, bivouacking at night. Sometimes they came under sniper fire from the Turks, who were supported by German units. In one incident Dalton’s superior, Lieutenant Colonel John Craske, commander of the 6th Leinsters, was wounded by a Turkish marksman.20 The 29th Brigade with its two Leinster battalions was in support during some significant operations, including the capture of the Hareira Redoubt, a Turkish fortification, by 2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers of the 31st Brigade.

Turkish forces pulled out of the symbolically important city of Jerusalem, clearing the way for Allenby’s forces to occupy the city. In a letter to a relative in the US, Dalton referred, with a note of pride, to the capture of Jerusalem on 9 December. He said that a couple of weeks ago they had taken Jerusalem and tomorrow ‘we are going to do a big offensive, and I hope to come out of it alive’. He said he considered himself ‘really lucky’ to be alive after the amount of war he had seen.21 The Ottoman Turks had captured Jerusalem in 1517. Now the city where Christ once walked was in the hands of the British – and an Irish division had played a role in its capture.

Bad weather delayed Allenby’s next offensive to push the Ottoman Army further north. The 10th Division had to suffer through a bleak, rain-sodden Christmas in the district of Beit Sira, about twenty-five miles northwest of Jerusalem.22 On St. Stephen’s Day, the division attacked the Zeitun Ridge, a well-fortified Turkish position protected by numerous machine gun emplacements. Attacking troops had to negotiate steep ground and deep ravines or wadis. Dalton’s battalion was fortunate. When they advanced to occupy a position at Shabuny, the 6th Leinsters found the Turks had fled, under enfilade fire from the 1st Leinsters and the 5th Connaught Rangers.

On 4 January 1918 the 6th Leinsters moved into an area around Suffa, northwest of Jerusalem, occupying part of the long line held by the Corps, and would stay there for some weeks, living among the stony, barren hills. Dalton was among those who lived in tents. With the occasional heavy rain it was not the ideal time to camp out. The work of the battalion included road making, disrupted by heavy falls of rain. Those not employed on road work were engaged in training.23 One of the roles of the battalion was to repel any counter-attack by the Turks. Dalton, carried out extended reconnaissance patrols on horseback, shadowed by covering parties. Dalton gained considerable experience of negotiating his way on horseback through rough, rocky terrain and the local wadis.

Lieutenant Dalton’s role was that of Assistant Adjutant, engaged in mainly administrative work, such as courts martial arrangements, and drawing maps of the positions held by the various units in the area. He was, apparently, an efficient typist, pounding away on a typewriter and producing circulars for the battalion.24 From mid-January until the following April, Dalton kept a diary, written in small neat handwriting in a military notebook, using just one side of each page.25 A picture emerges from his writings of a rather boyish figure, who regularly writes home to ‘Mamma’ and ‘Pappa’. He was delighted to get letters from his parents, and also from his younger brothers Charlie and Brendan, and from friends. Like many a soldier at the front he read and re-read these precious letters. He was generous in sending a ‘check’ (he uses the American spelling) to his parents to buy presents ‘for the boys’. Apart from writing to members of his family he also wrote to a young woman whom he calls ‘Kittens’ – possibly his childhood sweetheart Alice whom he would later marry. There were other female friends with whom he corresponded – Mai Broderick and May Doyle, as well as a person called Marnie.26 From his diary and from other evidence, Dalton emerges as a prolific letter writer, corresponding with relatives as far away as America.

For a young soldier in the desert hills, far away from home, letters assume enormous importance – the writing of them and the receiving of them. Dalton in his diary makes careful note of letters written and received. Some letters reached him literally months after being posted. He was often homesick, and felt particularly down or even irritable when the mail arrived and there was no letter for him. At one stage he remarked in his diary, ‘I don’t think I would feel so fed up as I do, if I could only see the dear folks at home occasionally…’ However, he also reflects that ‘there are fellows out here who have not been home for two years’.27 Although Dalton was extremely busy at times, he also found spare time to write letters, read novels, or kick a football around. He tried to learn foreign languages but gave up Arabic and Russian as too difficult. To get photographs of loved ones or presents from home in the post was a great morale booster. He was delighted when plum pudding arrived and he shared it with his fellow officers. ‘It was simply topping and everybody was pleased.’ On another occasion he received the Christmas edition of Our Boys, the magazine produced by the Christian Brothers for their students – an event significant enough to be mentioned in his diary.

Dalton was diligent in fulfilling his religious duties, and attended 07:30 Mass every Sunday morning. He was still in his teenage years and his boyish exuberance emerges occasionally from entries in his diary – he notes that he cut the nose of the Padre, Father Burns, while they were playing a game of ‘bombing each other’. There were times when he felt very down, and times also when he felt unwell or suffering from fever – possibly due to malaria.

To compensate for the homesickness, there were interesting sights to see. Jerusalem was not too far away, and was one of the places that soldiers stationed in the region liked to visit on leave. An entry in Dalton’s diary indicates that he was particularly intrigued by the sights of the Holy City – he mentions doing a sketch of the Damascus Gate, which he sent to his father.28 (In another entry he mentions sending drawings to his brother Charlie, probably the next best thing to sending photographs of local scenes. Another drawing, a self-portrait of himself in uniform and wearing a sun helmet, survives in his papers in the National Library.)

While Dalton’s battalion was not engaged in combat at this period, there were regular reminders of the war. One day he saw an aerial fight between a German and a British aircraft – apparently the latter brought down the former without too much difficulty. In the latter part of January, Dalton received a grim reminder of the threat posed by German submarines to allied troopships, when 2nd Lieutenant O’Mahony joined the battalion – he was one of the survivors when the troopship Aragon was sunk by a German submarine outside the port of Alexandria on 30 December 1917, causing the deaths of more than 600. Dalton got a first-hand account of this horrific event from O’Mahony.29

There was a social side to a young officer’s life in the hills. Visits were made to other battalions and regiments, and an officer going to Jerusalem or Cairo on leave would often bring back presents or souvenirs for his associates. Dalton notes that Bill Cooke returned from Cairo ‘with a good supply of cigarettes for me’, and Major Graham returned from Jerusalem with souvenirs for his colleagues. ‘Mullins got a lovely book of pressed flowers. Petrie got a lovely little box of polished olive wood.’ Dalton himself received from Graham several postcards ‘which I intend to send home today’. Lt. Colonel John Craske, the veteran battalion commander, seemed to take a paternal interest in the progress of his subordinate officers, and Dalton notes that Craske attended a dinner to celebrate the award to Captain Monaghan of the Military Cross.30 There was one officer whom Dalton disliked, Major King, with whom he had arguments on those two ever-sensitive topics – politics and religion.

On 4 February Dalton undertook a long reconnaissance tour on horseback with Major King and Lieutenant Haile, and their first port of call was to ‘Connaught Hill’ – the headquarters of the 5th Battalion of the Connaught Rangers, which formed part of the 29th Brigade. Dalton and King paid a visit to Lt. Colonel Vincent M.B. Scully, commander of the battalion. Dalton formed the impression that Scully was rather ‘fogged’, that is uncertain, about his duties in the event of a Turkish counter-attack, a contingency which Dalton considered absurd as he believed the Turks did not have the courage to ‘storm our present position’.31 Dalton records how he and the other members of the party rode on, shadowed by a party providing protection, passing through Kurbetha Ibn Hareith and through the Wadi Eyub. This was an area of rocky hills, with stone walls, bridle paths and olive groves. They watered their horses at a well in a place described by Dalton as Job’s Tomb. Because of a threatening storm they galloped towards home until the ground became very difficult, and he considered they were lucky to get back to base before the storm broke. On another reconnaissance tour, covering fifteen miles, Dalton rode the Adjutant’s spirited horse, and observed that the animal ‘had a mouth like iron and covered my hand with welts’.32

Exasperated by the intermittent heavy rain that sometimes penetrated his bivouac, Dalton remarks after once such occurrence that in the next war he will be a ‘conscientious objector’. There seems to have been limited contact between the military and the Arab population. One day Dalton records that he accompanied the Medical Officer (MO) ‘on his rounds of the natives’. On another occasion he encountered an Arab youth who had fled from the Turks, and for whom he felt sympathy. The youth, who spoke English, told how he was educated by the Christian Brothers – probably a reference to the De La Salle Brothers – in Jerusalem. The youth gave a graphic account of how the Turks ‘robbed the people’. Dalton remarks that he felt for the youth because he was only sixteen years of age. He comments: ‘I used think that Irish Catholics were the most oppressed but I have changed my opinion now.’33

After some weeks in Suffa, Dalton was made an Intelligence Officer (IO), in addition to his duties as Assistant Adjutant, but his work as IO seemed to consist largely of filing intelligence summaries from the division. Nevertheless, this experience would doubtless have given him insights into Allenby’s strategy, and contributed to his military education, giving him a lasting appreciation of the value of intelligence in military operations. Some of the reports he received seem to have been of a very general nature, to do with matters like peace conferences and offensives on other fronts.34

Instructing at the Sniper School, El Arish

On 13 February Dalton records that he was informed by Captain Monaghan that Division had recommended him for good work in regard to Intelligence and that he would leave the Battalion on the 14th, the following day, to take up his next position as Instructor in sniping and intelligence duties at the Army Sniping School, El Arish, in the northern Sinai Desert in Egypt. Dalton had been in correspondence with one of the officers running the school, Captain Chalmers of the 3rd Dragoon Guards, apparently giving Chalmers the benefit of his experience as regards tactics. It also emerged that Dalton kept a notebook on scouting. Chalmers had written to Dalton in January thanking him for his information and asking for more, as he considered that the sniping school benefited from every little piece of information from those ‘on the spot’.35

Dalton appears to have been popular with his fellow officers. On the night before his departure, there was a big attendance of officers from the battalion at a rousing send-off dinner in the mess. Dalton recorded that the main dish on the menu was ‘kid’ – a small goat that had been stolen from the 31st Field Ambulance ‘whose mascot it was’. A plentiful supply of whiskey seems to have added further to the merriment. There was a sing-song and there were farewell speeches and toasts, and Dalton was given a rousing cheer.36 Early next morning, Dalton set off on his long journey to El Arish. He was accompanied by two young fellow officers of the Leinsters, Lieutenants Cooke and Haile, who were being transferred from the infantry to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) at Heliopolis, near Cairo. Dalton may also have been tempted to transfer – he would later reveal that he was of a mind to join the air force. For the first leg of the journey they travelled by road to Latrun, a distance of about twelve miles. A lorry later took them to Ramleigh (Ramallah) where they boarded the night train to Kantara.

After their journey through the Sinai, they arrived at Kantara, situated on the Suez Canal, early next morning. Kantara, formerly a small village with a few mud houses and a mosque on an ancient caravan route through the Sinai to Palestine, now accommodated a massive British military base camp and supply depot. Kantara had grown, due to the British war effort, into something resembling a modern metropolis, with miles of railway sidings, workshops, tarmac roads, electric light, cinemas, hospital facilities, churches and even a golf course. There were clubs, including a very efficient YMCA establishment, and Dalton records that he had a ‘lovely breakfast’ in the officers lounge there. Dalton was disappointed to find that most of his kit that had been put in storage at Kantara had disappeared, but he was issued with a tent and other items from the stores, including silk pyjamas. He was particularly pleased with the latter, describing the pyjamas, in the parlance of the day, as ‘top hole’. After lunch in the mess, Dalton bade farewell to his travelling companions as they continued on their way ‘in very good spirits’ to Cairo.37

Dalton took a train to El Arish, with just one other officer in the carriage. Nurses got on at a stop en route and eventually Dalton tried to break the ice with the ‘nicest looking’ of them by offering her his ‘British warm’ – an officer’s great coat – as it was cold. He was rebuffed, instantly regretting that he had spoken at all. However, another nurse asked him where he was going, leading to a general conversation that developed into a sing song which helped to pass the time.38 It was late when Dalton arrived at El Arish. He began his duties at the school of instruction on 18 February, but found that his own services as a lecturer were not required until a new course started. He was told to assist Lieutenant Springay for the remaining week of the current course – Springay was giving a class on observation. Meanwhile, Dalton decided to take advantage of the golfing facilities at El Arish. On 23 February there is a simple entry in his diary, ‘Played Golf’. This is the first record of Dalton playing the game that would take on a highly important role in his life. He played regularly during his stay in El Arish, and he would recall later that it was in Egypt that he played golf for the first time.

He had some leave and decided do some sightseeing. On 24 February he travelled to Cairo by train via Kantara, and checked into the luxurious Grand Continental Hotel on Opera Square. The Continental was then one of the great hotels in Cairo, renowned for its spacious and very elegant terrace area, where patrons could relax over drinks or a meal. The hotel was popular with members of the British armed forces – earlier in the war, as a young 2nd Lieutenant working in intelligence, T.E. Lawrence had resided there. Having spent a long period of storms and heavy rain living in a tent, Dalton must have revelled in the luxury of a comfortable bed in a good hotel. He records in his diary that he had breakfast in the hotel after a good night’s sleep ‘and a lovely hot bath’.39 He went out to see the exotic sights of Cairo, and the following day continued with his sightseeing, visiting the other great hotel in Cairo, the historic Shepheard’s Hotel, and also the fashionable café, Groppie’s. Some of his fellow officers were also on leave, and he went about ‘buying stuff’ with ‘Timmins and Billie Martin’. Some nurses from Alexandria, where important military hospital facilities were located, were also staying at the Continental, and Dalton had tea and dinner with them. He became particularly friendly with one of the nurses, Sister O’Brien, and he went for a [horse-drawn] garry drive with her, getting half-way to the pyramids. Dalton enjoyed the outing enormously, commenting in his diary that he had a ‘top hole’ time. He and his companion had coffee back at the hotel ‘and went to our respective rooms’.40 The next morning he took it easy in the hotel, playing a game of billiards. He met up with another officer from the 6th Leinsters who was also on leave, Captain Alan Brabazon (22) from a well-to-do Church of Ireland farming family in County Westmeath, and went to Groppie’s for tea. (Brabazon was destined to die the following month from a sniper’s bullet.) Dalton had lunch with another officer called Fry, and in the afternoon went to a social event organised by the wife of General Allenby.

Dalton records in his diary how he was introduced to Lady Allenby ‘and had the pleasure of procuring a cup of tea for her’.41 Probably impressed by Dalton’s charm, she introduced him to Countess Hariaina Pacha, who was accompanied by her daughter. Dalton, who had an eye for attractive young women, was probably more interested in the daughter and he asked her to dance. As they took to the floor the young woman seemed to be mistaken about the identity of her dancing partner. She appeared to think Dalton was a French aristocrat, causing him some embarrassment by addressing him as ‘Monsieur le Duc’. However, he admits that he did not really mind the fact that she was labouring under a slight delusion ‘which my poor knowledge of French was unable to allay’.42 (It is also possible that the young woman was having some fun at Dalton’s expense.)

After his interesting break in Cairo, Dalton returned to El Arish. He resumed his instructor duties, and on 4 March, he mentioned in his diary his twentieth birthday. He felt ‘lonely’ but ‘busy’. He would remain busy over the following weeks, although he still found time to play golf from time to time. As he concentrated on work, the entries in his diary became shorter and less detailed. The topics covered in the courses he gave included observation; scouting; intelligence summaries and aerial photographs. The latter topic indicated a particular interest on Dalton’s part in air reconnaissance, and during the Irish Civil War he would show a particular interest in using aircraft to gain intelligence on opposing forces.

In an offensive in April, when the 6th Leinsters was tasked with taking a high peak area near the village of Kefr Ain, the battalion came under Turkish artillery and machine gun fire and suffered casualties. Among the injured were some of Dalton’s officer colleagues, Lieutenant Hogan, 2nd Lieutenant McDonnell and Captain Powell. Dalton’s sojourn at the school in El Arish meant that he missed out on these engagements with the enemy. While he probably would have wished to be where the action was, El Arish was a safer place in which to be located. Once again, from the point of view of survival, his luck had held out.

Dalton appears to have pleased his superiors in the way he performed as an instructor in the sniping school. A memorandum dated 22 May 1918 drawn up by Captain Percy H. Manbey on behalf of the Major commanding the El Arish School of Instruction, of which the sniping school was part, declared that Lieutenant Dalton has given ‘entire satisfaction’.43 The fourteen-week stint as a sniper instructor inspired Dalton to write a poem, The Sniper. He wrote it on 19 May, towards the end of the course during which he essentially taught men to stalk and kill the enemy. The poem is a grim reflection on the heavy responsibility on the shoulders of a marksman whose job it is to kill an enemy soldier. He knows that his shot will cause a woman’s tears, and that a mother’s heart will be torn apart. But he is also conscious that a comrade died at his side at dawn [at the hands of an enemy sniper], ‘died with a gasp and nothing more…’ He reflects that we are all marked with the hand of Cain. ‘Thus shall it be, a life for a life…’44 He closes with the Latin motto of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, Spectamur Agendo – ‘Let us be judged by our acts.’

Return to France

The British Army decided that it needed the 6th Leinsters on the Western Front. On 23 May Dalton and his battalion boarded the vessel Ormonde at Port Said and sailed for France, arriving in Marseilles on 1 June. The battalion travelled by train to Aire in northern France, near the border with Belgium, and set up camp. The usual training and fatigue work was carried out, and anti-malaria quinine treatment was administered.45 One of the great advantages of the transfer of the 6th Leinsters to northern France was that all ranks became eligible for leave – some had been serving continuously abroad for three years.46 Dalton was promoted to Captain on 3 July, and was also given the opportunity to visit Ireland on leave.

In the meantime Dalton’s skills as an instructor were called on once again – in July he gave a Lewis gun course to newly-arrived American troops at the Samer Training Area near Boulogne.47 They were part of the rapidly expanding American Expeditionary Force preparing to fight on the Western Front. It was decided that those American units deployed on the British front would use certain British weapons, such as the Vickers and Lewis machine guns, as opposed to their own American-supplied weapons. As a result, American officers and non-commissioned officers needed instruction in the British weapons so that they could, in turn, instruct their own men. Captain Dalton, ever conscious of his American birth, was clearly very pleased to meet the American military men he instructed. To ease them into combat conditions, American units were sent for further training with British forces in front line positions, and there is an indication that Dalton was in action with American troops around this period. In a letter to his American cousin, Frances O’Brien he said that he had the opportunity of fighting alongside United States troops, and in a tribute to their bravery said it was ‘glorious’ to see how the American soldiers fought.48 On 29 June 1918, the Commandant of the VII Corps Lewis Gun School recommended Dalton as ‘a good instructor’.49

In his 4 August letter to his cousin, Dalton wrote that he had received two weeks leave to go home to Ireland, and that he was about to transfer to the Royal Air Force (RAF), as he believed nothing could equal the difficulties and dreadfulness of an infantry soldier’s life. As indicated above, while stationed in Palestine, two of his fellow officers had transferred to the air force, and he may have considered following in their footsteps. Flying also probably appealed to his spirit of adventure. It is unclear if Dalton pressed ahead with an attempt to transfer to the RAF – certainly, he remained in the infantry until demobilized, but in his later army service in Ireland, he would show a keen interest in military aviation and have an appreciation of the value of air support in military operations.

On 10 August, word came through that the 6th Leinsters battalion was to be disbanded. Later in the year, officers and men would go to other regiments such as the Connaught Rangers, while others, including Captain Dalton, transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the Leinsters. Meanwhile, in the latter part of August, Dalton went home to Ireland for a badly-needed two-week break. On 1 October, Dalton officially joined50 the 2nd Leinsters who were in Belgium at this period, taking part in combat operations as the war ground to a close. Once again, Dalton was deployed with a fighting unit. Lieutenant Francis C. Hitchcock of the 2nd Leinsters recorded in his diary for 4 October that heavy rain fell all day and a new draft of officers arrived.’51 It is likely that Dalton was part of this draft. (Hitchcock would later turn his diary into a book, Stand To: A Diary of the Trenches, 1915–1918.52 It remains one of the best memoirs to emerge from the Great War, written with humour and empathy, and giving a most vivid day-to-day account of life as a junior officer in a time of war.)

The battalion moved to Ypres on 5 October. The British II Corps, in alliance with French and Belgian forces, was preparing a major assault on the German lines. The 2nd Leinsters were now part of the 88th Brigade of the 29th Division of II Corps. Hitchcock noted in his diary for 5 October: ‘At 5 p.m. the battalion paraded and moved off for Ypres for another offensive. It was raining heavily when they paraded and marched off.’53 On 13 October the battalion moved into position in trenches for the attack the following day. There was a heavy fog as the attack went in. Dalton’s battalion, 2nd Leinsters, was deployed among the advance troops of the 88th Brigade, fighting in the Ledeghem sector near Courtrai. Details are unavailable of Dalton’s role in the attack. During the fighting on 14 October, two members of the battalion carried out actions that would later win them the Victoria Cross, the highest British award for valour. They were men who Dalton would get to know quite well: Scots-born Sergeant John O’Neill, from Airdrie, Lanarkshire, and Private Martin Moffat, from Sligo. The liberation of the village of Ledeghem by the 2nd Leinsters and other elements of the 29th Division was still being commemorated annually in recent years by local dignitaries and members of the Leinster Regiment Association.

Deployment to Germany

Dalton went on sick leave for the first three weeks of November 1918.54 Meanwhile, after four long years the war was finally drawing to a close. Lieutenant Hitchcock recorded in his diary for 10 November that he and men of the 2nd Leinsters were marching to a rendezvous at the village of Arc-Anière when the Brigadier came galloping up to call out: ‘The War is over! The Kaiser has abdicated.’55 On the following day, 11 November, the Armistice came into force. As the war ended, all over Europe and further afield, one can imagine how parents and loved ones of combatants experienced an enormous sense of relief. Among many there was probably also a sense of anti-climax, as they wondered what had been achieved by such carnage. From later in November, until the following January, Captain Dalton was stationed in northern France. He was with the ‘L’ Infantry Base Depot (IBD), Calais.56 Hitchcock also spent some time at an IBD in Calais, in August 1918. In his memoir, he described the depot as being located ‘on the high ground overlooking the old historical town of Calais’. Accommodation was in tents, around which deep trenches ran at intervals in case of an air raid. The camp had suffered some direct hits ‘and numerous casualties’. There was an officers’ club where meals were provided.57

As Captain Dalton found, there was a social side to life in the depot. Among Dalton’s papers at the National Library in Dublin is a programme for a dinner dance at the ‘L’ IBD, Calais on 3 January 1919. Listed on the programme for the evening are some of the popular dances of the day – including the Waltz, One Step, Veleta and Lancers. On the back of the programme, a number of officers signed their names, with regiments also given – they include Irish regiments, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Leinsters, and English regiments such as the Essex and the Suffolk.58 No doubt, the end of the war added to the festive atmosphere. A few days later, on 6 January, Dalton entered Germany to serve with the 2nd Leinsters, as part of the Allies’ Army of Occupation of the Rhineland.59 (The occupation was mandated by the Armistice, and was carried out by French, Belgian, American and British troops.) In early 1919, Dalton was with a unit of the 2nd Leinsters stationed in a quiet rural village called Dhunn, about eighteen miles northeast of Cologne. This was in the outpost area occupied by the 88th Brigade. Lieutenant Hitchcock, who had been stationed here for a period and departed before Dalton arrived, found the area depressing. Platoons were billeted in ‘very dirty isolated farms’. It was also ‘bitterly cold and rained continually’.

Lieutenant Hitchcock was delighted to get orders to leave this bleak area peopled by hard-working farmers. He noted that, before departure, they received official news in December of the award of two Victoria Crosses to the battalion.60 The following month, January, somebody had the idea of gathering together, for a photograph, members of ‘D’ Company of the battalion who had been awarded decorations for bravery. The picture was taken outdoors, in a field or garden with a row of tall trees in the background. It is a most remarkable photograph and still survives as a treasured memento in the possession of Emmet Dalton’s daughter Audrey. It shows Dalton and Captain John Moran, both recipients of the Military Cross, with the two winners of the Victoria Cross, Sergeant O’Neill and Private Moffat.

While Dalton was stationed at Dhunn with ‘D’ Company, 2nd Leinsters, he spent time in training and exercises, which no doubt helped to further develop his military expertise. On 14 February 1919, Dalton drew up Operation Orders for the company as part of a battalion exercise involving an advance on the ancient town of Radevormwald.61 (Although Dalton had been promoted to Captain or acting Captain, he describes himself as ‘Lieut. J.E. Dalton’ on the handwritten document, and commanding officer of the company.) ‘D’ Company was to form the advance guard of the battalion advance, and he deployed elements of the company in various roles, in accordance with British military doctrine, outlining the relevant map references. Second Lieutenant Dorgan, with numbers 1 and 2 Sections and a Lewis Gun, was to be in the lead, acting in a ‘Point’ role. Flankers would be provided by no. 3 Section, while Lieutenant Johnson and no. 14 Platoon would form the Vanguard. The Main Guard would consist of two Platoons under the O.C. and his second in command. There would also be Connecting Files, provided by a Section, while two runners, Private Hart and Private Martin Moffat VC, would report to the Battalion HQ and act as Liaison. Experience in such exercises involving the deployment of infantry forces during military manoeuvres would, no doubt, come in useful when Dalton went on to become a senior officer in the National Army during the Irish Civil War. The experience would have been especially relevant as Dalton deployed his forces for the advance on Cork following seaborne landings in August 1922.

While stationed in the Cologne region, Emmet Dalton had a poignant task to fulfil. He went in search of a grave – the last resting place of a close friend, a fellow Irish officer who had been wounded, captured by the Germans and then died as a prisoner of war in October 1918, just before the Armistice. John Kemmy Boyle was, like Dalton, a northside Dubliner, and a fellow student at O’Connell School. The two men had both joined the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1916.

Already highly decorated, on 24 March 1918 Boyle was wounded and taken prisoner by the Germans while serving with 2nd Royal Irish Rifles (RIR). He died in a German Prisoner of War camp of pneumonia just three weeks before the Armistice. He was twenty-one years old. His remains lie in a war cemetery in Germany – Cologne Southern Cemetery. Dalton must, by now, have become used to comrades being killed in the war, but Boyle’s death appears to have affected him deeply. He was so moved that he wrote a very emotional seven-verse poem in memory of his dead friend – the handwritten text, in capital letters, on a single sheet of paper, is still preserved within the pages of his diary, among his papers at the National Library in Dublin.62 The poem is titled ‘Lieut. John K. Boyle M.C., My Dearest & Best Friend R.I.P’, and it is signed at the bottom, ‘J. Emmet Dalton’. The poem is undated, but the opening lines indicate that Dalton was inspired to write the verses after he found Boyle’s grave in Germany. ‘At last I have found your lowly place of rest…’ In the poem, Dalton reflects on his friend living in the ‘Hunnish Gaol’ for months and then dying with no mother or sweetheart or friend by his side. The tough-minded soldier-poet shows a compassionate, sensitive side in these lines in memory of his friend.

As Dalton was being demobilized, he received the usual letter from the British War Office to say that he was released from military duty. In his case, the release was from 4 April 1919. The letter stated that he would be permitted to wear uniform for one month only after date of release, to enable him to obtain plain clothes, but this would not entitle him to a concession voucher while travelling.63 The War Office sent the letter to Dalton at his father’s business address, 15 Wicklow Street, Dublin, where Dalton senior operated an importing concern. (The office would later move to 12 Wicklow Street.) The authorities had been informed that after leaving the army, Emmet would be working for his father on a ‘profit sharing’ basis.

Dalton’s service as an officer in the British Army, while often difficult and sometimes dangerous, had broadened his horizons. He had learned the art of soldiering, the finer points of tactics, strategy and leadership, and had developed abilities as a military instructor. He had quickly matured and acquired new skills – including horse riding. He had been to interesting places, including the Middle East. He had encountered people from outside his Irish Catholic middle-class environment. Among them were men from the ‘other’ community in Ireland, the Protestants, including members of the landed gentry, the middle class and the farming community. It had been a very interesting and challenging time in his life, interspersed with moments of great tragedy and trauma. Twenty-one year-old Emmet Dalton was now returning to a country in turmoil – the Great War had ended but his war-fighting days were far from over.