Читать книгу Dead Extra - Sean Carswell - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJACK, 1946

JACK SPENT the afternoon at the central library, digging up all the news he could on Wilma. Her death was barely a blip. The Los Angeles Times had a brief mention: “Local Starlet Dies in Tub.” The cub reporter who typed it up made a meal out of the handful of movies you could find Wilma in if you squinted at the right time. They were all B pictures with tiny budgets. Gertie would drag Wilma to the set on Wilma’s days off and remake her as a nightclub patron or a pedestrian or a Martian or a doll who elicited a wolf whistle or the world’s only red-haired Indian. There’d been one movie Wilma practically carried Jack to so that he could see her perform an actual line. Some mug with makeup for a beard got chased down the street by a dashing fellow. The mug crashed into Wilma. She said, “Saaaay. Watch it!” Jack applauded in the little theater off Figueroa. Someone in the back pelted him with peanuts and told him to can it.

The Times thought those movies the key to Wilma. They mentioned she’d been in over a dozen films prior to getting drunk and falling in her tub. There was no mention of her husband who, at the time, was believed to be dead in Germany. No mention of the book she wrote or her family or anything. All of that came out in the second piece Jack found about her. The obituary that Gertie had obviously written. Gertie would’ve paid by the word for that obit. She’d splurged the extra couple of pennies to add the words “beloved” and “cherished.” They caught Jack right in the back of the throat.

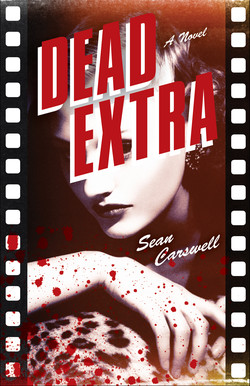

Other than the blurb and the obituary, there was nothing. No mention of a murder, an investigation, of questions raised, of neighbors concerned. Nothing. Just a dead extra and yesterday’s news.

Her book was in the racks. Jack climbed four flights of steps and wandered through a maze of shelves before finding the dusty copy. The card inside showed it hadn’t been checked out since September of 1944. He climbed back down the steps, brought the book to circulation, and checked it out.

He left the library and headed across downtown toward Cole’s. He would have to catch the interurban there and head back this way, past the library again and onto another car up Figueroa, but he needed a walk, some time to think, and maybe some luck at Cole’s. He strolled under the shadow of the Biltmore. Somewhere above the high arches and concrete balustrades were the rooms the hotel gave over to officers back from Europe—not the ones with bombardier badges like his. The ones with brass stars. The ones so far away from the action that, if you ran into them, you knew you’d retreated all the way back.

On the next block, he cut across Pershing Square. His father would talk about this being a meeting ground for fairies back in the ’20s. If the old man was paid to track down a hood or a thief light in the loafers, he’d come down to Pershing Square and start busting heads until he banged into one with a mouth that talked. By the time the war rolled around, the park was a patriotic site. He’d actually been hooked here, walking a downtown beat, pausing to stop under a palm and take in the statue of a soldier from the Spanish American War. A recruiter found him there, told him that his time with the force would count in his favor if he enlisted. He could be a sergeant, dropping bombs out of planes, fighting fascism and taking furloughs on the beaches of southern England.

Well, most of it was a sales pitch. The part about dropping bombs out of planes was true. And he had been a sergeant, for whatever that was worth.

When he reached the Pacific Building, he checked the counter inside of Cole’s, looking for a bare head with a bald spot the size of a yarmulke, looking for an arm stuck to a coffee cup that had been refilled a half-dozen times. This was the time of day when he could always find his old partner Dave Hammond here, like it was his office or something.

Jack didn’t see him at first. The place was buzzing. Customers flitted around from tables and stools like hummingbirds on bougainvillea, waitresses swooped in with food and out with dirty plates. Jack weaved through the tables to the counter, the place with the only open seats in the joint. A few gray-haired gentlemen lingered over their conversations there. And sure enough, though his arm had grown thin and the hair around the bald spot had turned white, Hammond couldn’t be mistaken. Jack took the stool next to him.

Jack didn’t address Hammond. He sat facing forward, waiting for the waitress. He pulled out a pouch of tobacco and started rolling his own. The waitress swung by. “Just coffee,” he said.

Hammond heard the voice and looked to his right. Jack kept his face forward, his hands on his cigarette. He could feel Hammond’s stare, almost hear the internal dialogue. Hammond brought that dialog to the external in no time. “Am I seeing a ghost?” he asked.

Jack slowly turned his head left. When he caught Hammond’s glance, he said, “Boo!”

Hammond jumped in his seat.

Jack smiled. It was a cruel joke, but he couldn’t resist it when the opportunity arose.

“Jack? Holy cow!” Hammond walloped him in the center of his back. “You’re alive!”

“So it would seem,” Jack said.

“I was at your funeral, kid. Christ, what happened?”

“At the funeral?” Jack asked. “I don’t know. I wasn’t there.” He pointed a finger at Hammond. “I hope you cried, though. I hope you turned to Gladys and cursed what a waste it was to lose a great man like me.”

Hammond smiled. He kept his hand on Jack’s shoulder and squeezed hard enough to crush the suit padding. “You son of a bitch. It’s good to see you.”

“You too.”

The waitress poured Jack’s coffee. He ordered a slice of peach pie.

“So what the hell happened over there? How’d you get yourself killed and come back to life?”

Jack lit his cigarette, watched the smoke gather around an overhead lightbulb. He gave Hammond the short version. “The plane I was in got shot down. I took a parachute ride followed by a little tour of Germany on my own. Sometime later, I ran into some Nazis who gave me a place to live for a couple of years. Now I’m back.”

Hammond scratched his balding head. “A little tour? Were you by yourself?”

Jack nodded. “I was the only member of the crew who made it.”

“So you were behind enemy lines? By yourself? For how long?”

“I didn’t count the days. A couple months, anyway.”

“Jesus, Jack. You must’ve seen some shit.”

Jack waved the comment away. He took another drag and felt the burn down deep in his lungs. “What about you? How’s life treating you?”

Hammond smiled. “Good. I got my pension. Little garden in the back. Coffee here in the afternoons to give Gladys a break. It’s the life of Riley.”

The pie came and Jack ate it. While he did, Hammond thumbed Jack’s library book. “I read this,” he said.

“Did you?”

“Sure. You know I always liked Wilma.”

“She was the best.”

“I made her funeral, too. I cried at that one. There wasn’t a dry eye in the house that day.”

Jack lifted his napkin to his mouth and gave his nose a surreptitious wipe while he was there. “Not many people there to cry, as I hear.”

“Oh, there were some. Me. Gladys. Wilma’s twin. A host of hash slingers from the joint she’d been working in at the time.”

“Did my pop make it?”

Hammond looked down at the linoleum counter. He shook his head.

Jack nodded, pushed away his pie plate.

The restaurant fluttered around them.

“What do you think of that story?” Jack asked.

“Which one?”

“Falling face-first in a tub.”

Hammond shook his head. “Hell of a way to go.”

“Fishy, too, huh?”

“How do you mean?”

Jack spun his stool to face Hammond the best he could. “Picture it for me, Dave. You’re five-foot-four in a four-foot-long tub. There’s a wall behind you and a wall next to you. You stand up in the middle. Something makes you slip. And what happens? Somehow, your knees don’t go down. They go up. Somehow your arms don’t go out. Somehow you contort yourself so that you land on your nose, and with enough force to kill you. What does that fall look like to you?”

“Strange things happen, Jack.” Hammond stood from his stool. He dug a handful of change from his pocket and dropped it on the counter next to his half-full coffee cup. “It doesn’t have to add up to anything.”

“It’s suspicious, is all. And you’re telling me you didn’t ask any questions.”

“I asked questions.”

“What did you find out?”

Hammond took a step away from the counter. “I found out not to ask questions, Jack.”

Jack rushed to fish out enough coin to cover the bill. He didn’t want Hammond to slip away this easily. “Hold up, Dave. I’ll walk with you.”

Hammond placed a meaty hand on Jack’s shoulder and pushed him back onto his stool. “Stay and drink your coffee, kid,” Hammond said.

“Are you telling me.… You’re telling me something. What is it? Were you scared off the case?” Jack asked.

“I wasn’t scared. I was just smart enough to know when to back off.” Hammond plopped his fedora onto his head. “Take my advice, kid. Back off.”

“Dave, this is my wife we’re talking about.”

“She’s six feet under. You’re above ground. Let her stay there and you stay where you are.”

“I have to know I’m outmanned before I do that,” Jack said, still sitting.

“You’re outmanned, kid. I’m telling you this because I love you. Play it smart. You didn’t survive months behind enemy lines and years in a POW camp just to get yourself killed over a dodgy story.” Hammond waved goodbye to the waitress. He turned back to Jack. “Ask the twin what happens when you stick your nose in the wrong places.”