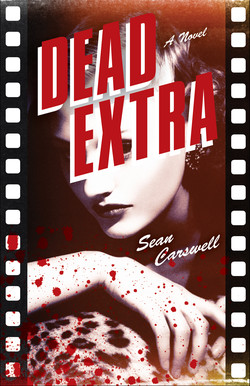

Читать книгу Dead Extra - Sean Carswell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеJACK, 1946

JACK LAY ABOVE his own empty grave. Brown grass poked into the back of his neck. He kept his eyes closed and his breathing slow, but he tried to stay awake. The springtime sun soaked into his darkest suit: a navy blue that could pass for black if not for the clear skies above.

His name was etched in the grave marker closest to him. “John Walter Chesley, Jr.,” it read. “Born March 31, 1920. Died February 8, 1943. Lost over the skies of Germany.” Most days, he felt like crawling into that empty coffin six feet down, but the fact remained. He wasn’t dead yet.

The stone next to it laid out the particulars for the woman Jack had widowed, who then widowed him. Wilma Greene Chesley. Born April 12, 1918. Died July 14, 1944. Wife. Sister. Author.

Jack hadn’t read the book yet.

Footsteps crunched in the grass nearby. A sharp heel dug into the dirt. The flat of the shoe hit the grass. The steady rhythm grew slower as it approached Jack. A shadow covered his face. The woman knelt down. She was so close that Jack could smell the soap she washed with. Cashmere Bouquet. The same brand Wilma used to use.

Quick as cats, Jack rolled away from her and popped up. He stood on the balls of his feet, ready to run or wrestle. Instinctively, his hand went inside of his coat. His fingers grazed the cool grip of his Springfield 1911. He looked across the gravesite.

The woman who had knelt at his side was standing now, flowers at her feet, hand over her chest. Her red hair was parted cleanly down the middle, the curls spun into submission and twisted into a hair comb on the back of her head. The afternoon sun pulled the freckles out from beneath her foundation. Her blue eyes burned underneath a furrowed brow. Christ, she looked identical to Wilma. If not for her broad-shouldered business suit, Jack could’ve convinced himself that he was standing over two empty graves.

It’s peacetime, Jack told himself. Hold it together. He pulled his hand out of his coat, smiled, and said, “Gertie.”

“Jackie?” Gertie glanced down at Jack’s tombstone and the imprint his body had left in the brown grass. “You’re alive, or you’re a ghost?” she asked.

“A little of both, I guess.”

Gertie put a hand to Jack’s face. “You feel alive.”

“That’s what I tell myself every morning. It gets me out of bed.”

“And you’re back?”

“Standing in front of you.”

Gertie pointed to the full vase atop Wilma’s grave. “Those are your flowers?”

“They’re Wilma’s now.”

Gertie looked at Jack. Jack looked at Gertie. The air hung still over Evergreen Cemetery.

Jack squatted down, picked up the bouquet Gertie had dropped, and handed it to her. She sniffed a pink lily. Her brow loosened but her eyes still burned. “So you’re alive and you’re back, Jackie. What now?”

Jack cast a glance over toward the potter’s field. “I don’t know.”

Gertie tossed the flowers on Wilma’s grave. She crossed herself and turned back to Jack. “Let’s get a bite and bump gums.”

Jack had taken the red interurban to Evergreen Cemetery. Gertie had driven. She drove them both to a sandwich joint off Alameda, not far from Union Station. The place was packed. They found a small table jammed between bigger tables. Gertie dug into her sandwich. She’d spent a long day on the lot, putting a shooting script back in order, running from one department to another to make sure everyone had the current changes, juggling a drunk screenwriter, a disengaged director, and the egos of a half dozen actors. This French Dip was the first food she’d touched since before sunrise.

Jack sipped his beer and watched her eat. His years in Germany made him wary of meat in general and suspicious of meats with sauce on them. He still smelled all his food before eating it. In a packed, smoky joint like this, where he couldn’t trust his nose, he let his sandwich sit.

Gertie polished off her plate, pickle and everything. She took in the immediate surroundings. To her left sat a few men in corduroy suits. They talked about fabric prices and young seamstresses. Another man, deeply engrossed in a newspaper, sat to her right. Gertie leaned in and caught Jack’s eye.

“I hear you’ve been at Wilma’s grave every day for the lasts few weeks.”

Well, that explained why Gertie wasn’t very surprised to see him. “Who told you that?” he asked.

“The guy who cuts the graveyard grass,” Gertie said. “He told me you come every afternoon at the same time and lie there in your suit. Said you turn on the waterworks when you think no one’s looking. Said you bring fresh flowers every day, and two times you polished her stone with car wax. That true, Jackie?”

“More or less.” Jack rubbed the side of his cheek to make sure it was dry. “Only I don’t wait until I think no one’s looking to turn on the waterworks. I just let loose when I have to.” Which might be any minute, what with Wilma’s spitting image staring him in the eye.

Gertie scooted even closer. “What do you know about Wilma’s death?” she asked.

Jack shrugged. “Just what they told me at debriefing.”

“Which was what?”

“She fell in a tub.”

“That’s it?”

“Is there more?”

“I think so.” Gertie leaned back in her chair. She took a pre-rolled cigarette, tapped it on her tin case, and placed it between her lips. Jack dug a lighter from his inside coat pocket and offered Gertie a light. She inhaled and blew the smoke out of the side of her mouth. A red fingernail dug a strand of tobacco off her tongue. Her eyes never drifted. She held Jack’s glance. “I think there’s more.”

Of course there was. Jack figured as much from the minute he’d heard the story of Wilma. It didn’t make sense. Wilma was too tall to land nose-first on the edge of a tub. If she slipped, she would’ve fallen out or dropped to her knees or cracked her hip on the edge. The physics of landing nose-first were implausible. Jack was no genius, but he’d always been smart enough to know bullshit when he heard it. So, when the doctor at debriefing told him about his wife’s death, Jack fought back the urge to kill.

Germany had taught Jack something about survival, something about tucking away his rage until he needed it, something about staying in the moment when he needed to be there. He prodded Gertie. “Like what?”

“I identified her body. Mom was off drunk somewhere. You were dead. A cop dragged me out of Musso and Frank’s to have a peek. And that’s all they gave me. A quick peek. It was enough to see bruises around Wilma’s throat.”

Something homicidal rumbled deep inside Jack, threatened to tear him apart. Simple routines helped him keep himself together. He took a pouch of tobacco from his jacket pocket and started to roll a cigarette of his own. “Sometimes blood pools in strange places.”

Gertie tightened her lips into a white line. Her nostrils flared as she took a slow, deep breath. She let the air out. “So I went by Wilma’s bungalow that night. No cops were there. I had a key but it didn’t matter. The lock had been busted. I turned on the lights and stepped into the empty little house and found all kinds of suspicious things. The needle was still down on her Victrola, at the end of a record. There was a little puddle of water in front of it. And right by the front door, speckles of blood. Like someone cut her foot and was running around anyway.”

“She could’ve gotten out of the tub to play the record, then went back in.” Jack dug a fingernail into the worn wooden table in front of him. “The blood could’ve been from any time.”

Gertie reached across the table. She put her hand under Jack’s chin and lifted his glance to meet hers. “Her bathrobe had blood and snot all over the front lapels. If you die naked in a tub, you don’t bleed on your bathrobe.”

Jack’s eyes followed a stream of cigarette smoke snaking its way up to the dark rafters.

“Plus,” Gertie said, “I talked to the neighbors.”

“And?”

Gertie reached into her purse. She pulled out a few sheets of paper. They’d been folded in half and in half again. She passed them to Jack. “This is what I think happened, based on everything I could find and what everyone who would talk to me told me.”

The paper was worn soft. It felt almost like a handkerchief. The typed letters looked to be pressed down by carbon, not ink. A copy. Gertie probably kept the original back at her place. Some of the letters along the folds had been worn away. Jack lit his hand-rolled cigarette. He took a deep drag, made a slow exhale. He angled the paper into a pool of light and read Gertie’s story.

It was too much. Too sudden. Jack could read some of the words, even make meaning out of some of them. Mostly, they were just squiggles on the page. More than he could take right now. He pretended to read and thought of the bruises Gertie had seen, imagined some tony bastard choking the life out of his Wilma. It’s peacetime, he told himself again. Hold it together.

“Nice story,” he said. He folded the pages and stuffed them into the inside pocket of his jacket. “You write like Dashiell Hammett. You should be a novelist.”

“This isn’t about my writing.”

Jack nodded. “So you think she was murdered.”

“Of course she was murdered, Jackie.”

Jack felt the weight of the Springfield on one side of his coat and the weight of Gertie’s story on the other. “And who was the man?”

Gertie pushed her empty plate aside and leaned her elbows on the table. She looked over Jack’s right shoulder as if she were hoping to find someone there who was entirely smarter and more reasonable than her former brother-in-law. “If I knew that, I’d do something about it.”

Jack pulled his uneaten sandwich closer. He wrapped it back up in its wax paper and stuck the whole thing in his outside jacket pocket. She must’ve tried to do something, Jack figured. Nearly two years had passed. Gertie must have followed trails until she was scared or bullied off. Jack would try to get that part of the story later.

He said, “Let’s say she was murdered. Just for the sake of argument, let’s say that.” He rubbed the back of his neck, felt the tension in his taut muscles. “Then what?”

Gertie burned into Jack with her blue eyes. “Then you find out who did it.”

“I find out who did it? Me?”

“Why not you? You were a cop.”

“I was a shitty cop. I never investigated anything.”

“You know the right people. You can get into the right places, find some answers.”

“I knew people. I don’t know them anymore.”

“Of course you still know them.”

“It’s been too long. Everyone thinks I’m dead.” He thought, but didn’t add, I’m mostly inclined to believe them.

“Excuses, Jack. You’re just giving me excuses.”

Jack shook his head. “I’m not sure what you want from me. I don’t know what you think I can do.”

Gertie stubbed out her cigarette and tapped her bun to make sure every hair was in place. “You can find the bastard who killed your wife, Jack.”

He took stock on the red car home. For two of the past three years, he’d been in a POW camp in Germany. There were also the months he spent alone behind the lines in Germany, and the months he spent after the camp, trying to make it home. The Army paid him a lump sum for those years. It wasn’t a fortune, but it was enough money to give him time to think. He didn’t want to go back to the force. He was no cop and he knew it.

He could’ve taken over his father’s PI business, but he was even less of a dick than a cop. And his father never really investigated anything. The old man had spent a life as a hired thug. Not much more.

The PI license was still around the house on Meridian Street. Same name as Jack’s, only missing the junior. Jack Senior wouldn’t be using it anymore. Like almost everyone else, he’d died while Jack was in Germany.

A baby in the back of the interurban screamed out. Her mother cooed and held the child close. Jack looked at the little boy swaddled in a blanket, snot dripping from his nose, spit gathering around his mouth as he screamed. Jack looked at the mother, with loose strands of hair falling onto her face and dried mucus smeared on her shoulder. A thought flashed across his mind before he could tuck it away: I dropped a bomb on that baby. That baby and his mom. He glanced around the car, saw men in factory blues, mechanics with motor oil wedged in the cracks of their skin, seamstresses with that sewing squint, maids and men in business suits, and women with bags of groceries. I killed the German equivalent of every one of them, Jack thought. I killed them all and slept through the night.

The next thought Jack didn’t want to think but couldn’t keep from bubbling up was this: wartime and Germany and Nazi soldiers weren’t the only things that drove him to kill. The war had taught him that most people can’t kill another person. Even when soldiers are getting shot at, even when their lives are on the line, most can’t shoot back. Or, really, they can shoot back, but they subconsciously shoot high or low or wide. Most men can’t shoot to kill. Most humans can’t kill other humans. But some can. For whatever reason. And Jack was one of those people who could. So it wasn’t that he didn’t want to find out what happened to Wilma. It wasn’t that he didn’t want her killer to pay. He just feared the horror show once he did find out. He wanted the killing to stop. For the rest of his life.

Jack pulled out his packet of tobacco and started to roll a cigarette. Small routines helped.

He’d have to find ways to keep his thoughts in check if he was going to look for the man who murdered Wilma.