Читать книгу The Immortal Beaver - Sean Rossiter - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface Beavers return to Dick Hiscock’s watery backyard

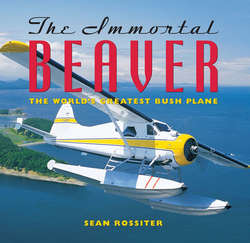

ОглавлениеFacing page: De Havilland Canada Heaven at Kenmore Air Harbor’s dock on Lake Washington, near Seattle. Kenmore has bean rebuilding and chartering Beavers and Otters for more than 30 years, and pioneered many now-tommon Improvements. GREGG MUNRO, KIN MORE AIR HARBOR

Our young American pilot stepped out of the freshly restored, pristine white Lake Union Air de Havilland Beaver onto the dock behind the Bayshore Hotel on Vancouver’s Coal Harbour waterfront. He could not have Keen more than twenty-five, h was all too obvious that he would have been very young in 1967, when he last Beaver was assembled. You like your pilot to be older than the aircraft if at all possible.

“Gotta treat this airplane with respect,” he said, reaching up to steady himself by grubbing the wing bracing strut. “It’s at least ten years older than I am.”

Respect it? He worshipped it. He was still briefing me after the half-hour Right as he helped me and the three other passengers out onto the dock at the company terminal on Lake Union in downtown Seattle. What an honour it was to fly a de Havilland Beaver, the greatest bush plane ever, he said. Did I know that the Beaver was named the year before as one of the ten outstanding Canadian engineering achievements of the past century?

Well, no. I didn’t.

He went on. Did I know we were just past the fortieth anniversary of the Beaver’s first flight on August 16, 1947? And that it is powered by an engine, the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior, that could become the first aero engine still in scheduled use a hundred years after it was designed?

We took off that summer day in 1988 with a lot of noise but no fuss of any other kind. Floatplanes are known for taking forever to get off the water, which is not the airplane’s natural element. Mounties who flew the Norseman, Canada’s first purpose-built bush plane, used to say its takeoff on floats was obscured by the curvature of the earth.

The impression that remains from our takeoff in the Beaver is of being in some cartoon airplane that stuck its nose up, gathered itself by collapsing back on its tail and floats, straightened itself out and leaped into the air.

If the takeoff was not sufficiently spectacular, the landing certainly was. The Beaver practically stopped in the air as it crossed over the Aurora Bridge, one of the stratospheric iron-age engineering wonders that connect Seattle’s seven hills high above intervening bodies of water. The airbrake effect of the flaps as our floats barely cleared the bridge’s streetlights was palpable and caused a faint ripple of alarm among the four passengers. We exchanged brief glances. But the Beaver was fully under control. This kid and his old airplane could fly. We alighted on Lake Union like some mallard skidding, straight-legged and leaning back, along the surface of a pond. Only images from animation describe the Beaver’s takeoff and landing performance.

So it was that, as so often happens with noteworthy Canadian achievements, it took an American to describe and showcase the Beaver to someone who ought to have known about it all along. Canada is such a strange place, so eager to dwell on its failures. There are, by my count, six books on the Avro CF-105 fighter-interceptor, of which six prototypes were made. One of these books is actually entitled Shutting Down the National Dream.

And yet this is the first lengthy account of the most successful Canadian airplane design ever, a design the merits of which Americans were among the first to recognize. The American armed forces bought more than one-half of the 1,631 Wasp Junior-powered Beavers built, and their requirements resulted in significant improvements in the basic airplane. It was the first foreign aircraft ever ordered in peacetime by both the U.S. Air Force and Army.

The de Havilland team had wondered whether to begin Beaver production three years before the Americans ordered it, when the market was still glutted with war-surplus planes. Instead, de Havilland Canada managing director Phil Garratt put aside the Beaver design studies to produce a military training aircraft, the DHC-I Chipmunk.

Building the first: twenty Beavers was considered a “million-dollar gamble,” as the company advertised it. They were right about that. The Royal Canadian Air Force bought none. Eventually, though, Beavers were sold to sixty-five countries, making this tough, hard-working little airplane one of Canada’s greatest export successes after lumber. Half-a-dozen land features in Antarctica are named for the Beaver, from which they were first spotted.

Only now that many of those Beavers sold abroad are returning to Canada, often as corroded hulks, and mostly in the region where they have yet to be replaced as reliable everyday transportation—along the rugged Washington-British Columbia-Alaska coastline—is the Beaver beginning to be fully appreciated as the engineering masterpiece it has been for nearly fifty years. As these hulks are returned to airworthiness, certified to carry twice the load they were originally designed to handle, we can see the Beaver’s unique place in the annals of aviation. No other aircraft in history was flying in greater numbers as it approached its fiftieth birthday than we re flying ten years before, when I flew from Vancouver to Lake Union and back. The Beaver has simply never been replaced. Only a Beaver can replace a Beaver.

Aside from my own revelation about the de Havilland Beaver from a young American whose name I had not the wit to ask, that same weekend happened to be fraught with weighty Canadian-American implications. I returned to Vancouver to see newspapers headlining the fact that the highest scorer in National Hockey League history, Wayne Gretzky, then the country’s greatest sporting treasure, had been sold to the Los Angeles Kings, setting off one of those paroxysms of self-examination that make up of much of Canada’s national discourse.

R.D. “Dick” Hiscocks, the aerodynamicist who shaped the Beaver, happens to live on the other side of Vancouver’s Stanley Park from the Bayshore. From his apartment he often hears Beavers revving up for takeoff. They can be distinguished from other piston-engined aircraft by the unbelievably loud Rrrr-aapp sound made by the Wasp Junior’s two-blade propeller, whose tips at full power approach the speed of sound.

Issued October 5, 1982, this Canadian stamp honours the Beaver prototype, CF-FHB. It is one of four stamps issued by Canada Post to commemorate aircraft that opened up the nation’s vast northern regions. The others pictured were the Fairchild FC-2WI, Noorduyn Norseman, and Fokker Super Universal. The artist is Robert Bradford. CANADA POST

The story of the Beaver’s origins is one of the early successes of niche marketing. Hiscocks is the first to say that the Beaver was a team effort. The renaissance man who would become de Havilland Canada’s greatest design engineer, Fred Buller, was responsible for most of what went underneath Hiscocks’s blunt-nosed shape. Garratt, the managing director, had been thinking about a bush plane even before the Downsview factory’s huge wartime contracts were cancelled in 1945, leaving the company with a superior design and production staff and the facilities to mass-produce advanced aircraft. Garratt envisioned an all-metal bush plane and had a preliminary design drawn by his chief design engineer, W. J. Jakimiuk, even before the war ended. Jakimiuk, a war refugee from Poland, happened to be a pioneer of European all-metal aircraft construction. Buller and Hiscocks, young engineers with rich wartime experience, reworked Jakimiuk’s ideas. As the design took shape over the next two years, Canada’s bush-flying community was intensively consulted—especially the pilots of the Ontario Provincial Air Service. Asked for his opinion, the dean of western Canadian bush flying, Punch Dickins, endorsed the design by agreeing to sell it.

The Beaver’s success was no accident. Extraordinary talent, capably directed from above and guided by the ideas of the people who would fly it, made the Beaver a milestone of aircraft engineering.

As we flew low over the San Juan Islands in the Lake Union Air Beaver—low enough to see people washing cars—I wondered whether our youthful pilot, knowledgeable as he was, fully understood the ancient design origins of the machine he was flying. The Beaver looks older than it is, an artful mix of sheer utility and conscious flair. Its ancestry extends back to the first fighters to engage the Luftwaffe at the dawn of World War II. It has the gracefully S-shaped trademark de Havilland fin that adorned the company’s wartime Tiger Moth trainer and Mosquito bomber. The Beaver’s throttle, propeller and fuel mixture levers move vertically in grooves in the middle of a “Streamline Moderne” dashboard—more of a dashboard than an instrument panel. The Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior powerplant is, by today’s standards, colossally noisy. And it is very close at hand.

“You hear big pilots say, ‘Why did you have to put the engine so close?“’ Hiscocks chuckles. “Well, the plane wouldn’t balance any other way.”

Radials also run rough, so everything vibrates. Other aircraft have been described as 10,000 parts flying in close formation, but very few of the others are still in the air.

The Beaver survives because it has enough thoughtful features to have been a reinvention of the bush plane. Four doors instead of the more usual one, the rear ones wide enough to roll an oil drum through. Most aircraft have their gas tanks in the wings, feeding the engine by gravity, but that means pumps, hoses and rickety ladders for refuelling. The Beaver’s tanks are under the floor, with fillers low on the fuselage. The fuel-drain stops are oversized so they can be unscrewed with mitts on. Engine oil can be thinned within the engine for easier cold-weather starts. Oil can be added in flight, although the process can be messy, from a filler spout located near the base of the control column.

Chief pilot Bill Pennings of Vancouver’s Harbour Air, who has logged a remarkable 10,000 hours on the company’s fourteen Beavers, says he has flown snowmobiles in them, a useful capability in the north, by removing the cargo doors on each side and letting the ski--doo’s front and back hang out. He has a 1991 Bush Pilots calendar in which the September photo shows a float-equipped Beaver towing a loaded barge. Heh-heh-heh....

Nearly a thousand of the Beavers built, by Hiscocks’s estimate, are still busy, an amazing number considering that they are used in the most forbidding parts of the world and are veterans of two wars. Half of those survivors are in Canada. They are worth about ten times the factory price, about $250,000, still a bargain compared with, say, the single-engine Cessna Caravan at $1.5 million. Dozens of little improvements have made it a better airplane. Today’s Beaver is cleared to carry more weight than when it came out of the factory at Downsview.

Dick Hiscocks talks about the immortal Beaver much as Leopold Mozart must have talked about his son Wolfgang. Likewise, the Beaver is a thing unto itself, an immediate success that is still irreplaceable along British Columbia’s convoluted coastline, darting through mountain passes into small bays and coves, alighting on the water and getting out again where few other aircraft venture.

By definition, of course, a classic comes close to perfection. Its essentials cannot be improved upon. Twice de Havilland attempted to increase the Beaver’s performance by installing yet more powerful engines. Neither time did the new model catch on—although the Turbo Beaver was the victim of a decision by new owners of the company to close the production line. An old aviation saying, often applied to the wartime de Havilland Mosquito, is that if it looks right, it will fly right.

Dick Hiscocks 1 ves in one of the most admirably sited apartment buildings anywhere: the one closest to Stanley Park’s southeastern edge. He overlooks an urban wilderness, where bush pilots fly executives to downtown office towers. He can see a continual parade of Beavers on final approach for landings in Burrard Inlet. They take off with a sound that reverberates around the grain elevators that line Burrard Inlet. One by one, the Beavers are returning to Dick Hiscocks’s saltwater backyard pond.