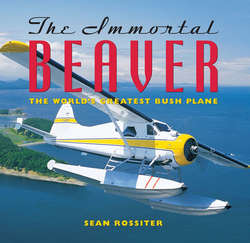

Читать книгу The Immortal Beaver - Sean Rossiter - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Four One thousand mosquitoes

ОглавлениеFacing page, top: The US government paid for Mosquito production at Downsview under for Mosquito production at Downsview under Lend-Lease, partly to have a claim on some of them as photo reconnaissance machine. They were known to the U.S. Army Air Force ax F-8s, Downsview built thirty-nine F-8s. Bottom: The first Downsview Mosquito, B. MkVII (B (or Bomber) KB300, the first of twenty-four of that model built there. It flew for the first time September 23, 1942. Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. demonstrated it in Washington and San Diego. BOTH PHOTOS: PETER M. BOWERS

The de Havilland Canada that had started the war building Tiger Moths and reassembling used and crated Avro Anson trainers was not the same company that built 1, 33 topics of the world’s first operational 400-mile-per-hour combat aircraft, the DH.98 Mosquito.1

The first DHC was a near-cottage industry that had congratulated itself on designing and fabricating streamlined landing-gear skis for the Rapide and a sliding cockpit canopy for the Tiger Moth. It was a small outfit with a managing director, Phil Garratt, who didn’t much care for titles and who knew the name of everyone else in the company.

The second DHC was a fully-integrated industrial organization, primed with government financing, embracing its own subsidiaries, subcontractors and satellite facilities, and even an elected local of the United Auto Workers. Several key engineers from Hartfield had joined the Canadian company, including the chief technical engineer since 1925, W.D. (Doug) Hunter, professionalizing DHC’s production methods. It was this second DHC that, by the end of the war, was fully capable of designing and manufacturing the line of Short Takeoff and Landing (STOL) aircraft that began with the Beaver.

Yet the changes that made the company more capable came at a huge price. In wartime, human costs are secondary to the overall objective. By the time DHC had expanded five-fold and was making its contribution to Canada’s war effort, there was no Phil Garratt at Downsview. He was sent into exile by the company’s new government taskmasters. A number of other company luminaries also left.

The only quibble about Garratt’s management style from those who worked for him is that it was a thing of the past. In his eye-to-eye meetings along the production line, which he toured every day, Garratt treated everyone as an equal—at least as much of an equal as anyone facing a man of his size and bearing could feel. He cultivated the wives of his workers, since they were his allies in getting the best out his work force. Phil was a pretty good listener, and by listening carefully he enlisted everyone in the plant in his personal quest to elevate DHC’s engineering and manufacturing capabilities. And yet, a management style that depends upon daily personal contact is better suited to a smaller company addressing a market niche with carefully conceived products than to the far-flung industry DHC became during the war.

“Phil Garratt didn’t believe in formal organization,” aerodynamicist Dick Hiscocks recalls. “He didn’t like titles. He said, ‘You know what you’re here for. Go and do it.’” Hiscocks remembers appealing to him at one point after the war for more of an organization chart in engineering. “He said, ‘Your job is to be where you’re needed.’”2

“He gave us a lot of freedom. We never punched time-clocks. People came in late and stayed later. We didn’t ask for time off. Of course, you’d come in on Sunday, too.

“Jakimuk encouraged people to come forward with their ideas—like Fred Buller. I wasn’t used to that in a senior man. It was a very co-operative, friendly atmosphere.”

A family is the term many oldtimers use to describe the pre-Mosquito DHC. In fact, a lot of de Havilland was families. There were, among many others, the Burlison brothers, George and Bill, who, with their father, had worked for Canadian Vickers ever since they were building varnished mahogany-planked Vedette flying boats. Or John and George Neal and their sister Kay, each a pioneer there. John was the first Neal to work at DHC, a distinction in itself. George float-certified the Beaver and took the Otter up for its first flight. Kay Neal’s career at DHC personifies the wartime growth of the company. Originally a seamstress, she rose from Betty McNicoll’s dope shop, where she fitted snug fabric skins to stick-and-wire biplanes and painted them with dope to form a tough, slick surface, to fabricating bulletproof rubber fuel tank liners for Mosquitoes in a shop filled with potentially explosive fumes. (No wonder Kay eventually became secretary-treasurer of de Havilland Local 112 of the Canadian Auto Workers in 1949.) Phil knew them all before the wartime surge in employment made knowing every employee’s name out of the question.

The transition from one type of organization to the other was an intense, painful sidelight to one of the most glorious chapters in aviation history: the often-told story of the DH.98 Mosquito’s secret development in an old mansion, Salisbury Hall. How the project persevered despite the determination of British aircraft production czar Lord Beaverbrook to kill it—Beaverbrook is said to have ordered it closed down three times. How the company’s test pilots, including Geoffrey de Havilland Jr., overcame with spectacular flight demonstrations the Royal Air Force’s early reluctance to embrace the cheeky speedster that would soon interrupt speeches by Hermann Goering and Joseph Goebbels in Berlin, in broad daylight, five hours apart on the same day.3 Mixed emotions remain with the Downsview veterans from the company’s difficult metamorphosis into a prime contractor for what was, until the last year of the wat, the Allies’ fastest aircraft.

Garratt masterminded this growth. In the year leading up to the decision to build the Mosquito, DHC’s staff had grown 140 per cent. By March 1942 the parking lot was being expanded to handle the cars of 2,400 employees, and a new cafeteria had replaced the circus tent in which workers had been lunching. By the end of 1942 DHC’s employees had more than doubled once more.4 Hotson remembers that it seemed at the time that no amount of new square footage would be enough.

Managing that kind of growth requires creativity and the ability to adjust, but as the company grew it became less and less the kind of place where the top banana could walk the production lines every day, let alone know all the employees’ names. The organization chart was being revised monthly. It was no longer a family-type operation. Garratt deserves credit for overseeing such explosive growth, which brought with it new requirements for internal communication, personnel and, above all else, training. But a gentleman with the personal touch is not necessarily the right guy to push production hard.

Lee Murray, Garratt’s predecessor as DHC managing director, who had since become GM at Hatfield, arrived at Downsview at the end of July 1941 to cast his sympathetic eye over the Canadian outfit’s production potential and requirements. “A mound of drawings” is Hotsor’s aptly vague characterization of the Mosquito production materials that soon arrived from the English plant that had run less by modern methods than by its employees’ skills and memories. There would also be shipments of vital parts for twenty-five aircraft and a completed Mosquito Mk.iv to show how it all went together.

Murray’s report led to orders a month later from the British Ministry of Aircraft Production for 400 Canadian-built Mosquitoes. These would soon be designated Mk.XX—an equivalent of the Mk.IV bomber version, powered by the American-built Rolls-Royce Merlin V-12, the Packard Merlin 31.

Soon after, Doug Hunter and Harry Povey arrived from Hatfield after a trans-Atlantic flight that was, for that time, a marvel of time management. “[They had left] England on Thursday and begun work in Toronto on Saturday” is how Fred Hotson summarizes their then-amazing experience. After that, however, flying across the Atlantic lost much of its charm for Hunter. He may have thought his luck couldn’t hold out indefinitely, or perhaps he changed his mind once ocean voyages became less stressful with the demise of the U-boat threat.

Hunter immediately became chief engineer of DHC, a position fully equal to chief design engineer Jakimiuk’s—and, at that moment, more valuable to the company. Hunter was regarded as a typical product of the parent de Havilland company.

“He was a well-educated man. Hunter was not a deep technical engineer but he was a very practical one,” in Dick Hiscocks’s estimation. “He had mastered the art of getting people to work together. During wartime, things were turbulent and nerves were jangled, and he had a very soothing influence on the more temperamental characters in the engineering department. And, like Garratt, he was a very humane man.”

Hunter had begun as a draftsman with one of the original British aircraft companies, the Grahame-White Aviation Co., forerunner of the great Bristol Aeroplane Co., de Havilland’s only British rival as a combined engine and airframe producer. George White acquired the land for the U.K.’s post-World War I display flying centre and today’s RAF Museum, at Hendon. Hotson remembers Hunter as “always immaculately dressed, spoke quietly, flicked his cigarette ashes over his shoulder, and punctuated every conversation with ‘Quite!’”

Hunter’s travelling companion, Harry Povey, who had been with de Havilland a year longer than Hunter, was slicked-back and rotund to Hunter’s grey-haired and aristocratic spareness. Povey has been described as “an aircraft production engineer without peer.” His first move at DHC was to ask for a new plant to build Mosquito fuselages.

The fuselages were formed in halves over concrete forms, using heat-treatment in huge autoclaves to shape the seven-sixteenths-inch-thick plywood left and right sides. Stiffeners and equipment were added before the halves were joined along the top and bottom.

DHC’s wing subcontractor was the farm-equipment manufacturer Massey-Harris of Weston, which had supplied Anson wings to Downsview. R. B. (Bob) McIntyre began his long association with the DHC engineering department as chief engineer of Massey-Harris, one of the most reliable suppliers the wartime DHC had.5 Their record of delivering Anson wings made Massey-Harris de Havilland’s first choice for Mosquito wings. They delivered the first set May 9, 1942. Always ahead of schedule, McIntyre and his workers became victims of their own efficiency when changes to the specifications of aircraft on the production line obliged Massey-Harris to modify wings already built but waiting in storage at their plant. McIntyre, who was with DHC by 1944, was a first-rate thinker who became a talent magnet for the company, recruiting, among others, Fred Buller.

Aside from the problem-free wings, the Downsview Mosquito program’s early setbacks were all too prophetic. A consistent 2 per cent loss rate for important drawings shipped from England was only the beginning. They arrived as microfilm, which had to be translated into full-size profiles and thence to huge sheets of plywood on the lofting-shop floor in mid-October. Lofting, the process of transferring full-scale drawings to raw materials from which the first parts are made, was a normal part of building any new airplane. It was just that DHC had never done that before. The Mk.IV pattern aircraft, RAF serial DK 287, shipped in mid-September, was delayed and damaged en route. But a fuselage jig did appear from England two weeks before Christmas of 1942, allowing a first fuselage shell and a duplicate jig to be available by mid-March.6

By May 5, 1942, Phil Garratt was on his way to meetings in England with a contract for an additional 1,100 Mosquitoes, financed by the U.S. Lend-Lease program. As the Mosquito’s impressive speed and load-carrying capacities became known, a bidding process began to assert itself for the ones being built at Hatfield, and later at Leavesden and Standard Motors at Coventry. The pressure to expand production was unrelenting. Every air arm that didn’t have Mosquitoes wanted them—even the Luftwaffe. Goering’s insistence on a night-fighter with equal performance led to an impressive German rwin-engine fighter, built largely of wood, called the Focke-Wulf Ta 154 Moskito. Only thirty were built.7

Hap Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Force, wanted hundreds of Mosquitoes and was prepared to trade P-51 Mustangs for them. In fact, the Americans were underwriting Downsview production with a view to siphoning off Mosquitoes built to U.S. specifications for themselves. To meet all these demands, the Mosquito became a jack-of-all-trades: fighter-bomber, photo-reconnaissance aircraft, night fighter, Pathfinder target-marking aircraft. Leonard Cheshire, VC, commander of 617 Squadron, the famous Dambusters, wanted a pair to mark targets for his precision-bombing Lancaster colleagues.

With the first Downsview example near completion, Garratt left his meetings committed to turning out eight more Mosquitoes during the rest of 1942, and to reaching a production tempo of fifty per month in a year’s time.

Despite the close proximity of its serial number to that of the first Canadian-built Mosquito, KB336 is an indication of how quickly models changed on the DHC assembly-line. This B. Mk.20 was part of the fourth batch, and approximately the 265th Mosquito built at Downsview. It is preserved at Canada’s National Aviation Museum, Ottawa. PETER M. BOWERS

KA 117 was one of 338 solid-nosed, eight-gun FB.26s built at Downsview. These versatile machines could also carry 2,000 Ib of bombs. By early 1945 many Canadian-built Mosquitos had logged 50 sorties over Europe. Photographed in England in November 1945, KA 117 had been converted to a dual-control trainer. PETER M. BOWERS

The first Canadian-built Mosquito, RAF serial KB300, flew on September 23, 1942. One month later, Geoffrey de Havilland Jr. demonstrated it at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, the USAAF’s flight test centre; then at Boiling Field, Washington D.C., handy to the Pentagon; and then, that December, at the U.S. Naval Air Station at San Diego. The original Mk.IV pattern aircraft from Hatfield, DK 287, was then made available for intensive evaluation at Wright Field in March 1943.

For the most part, despite Hap Arnold’s enthusiasm, the Americans were unimpressed. Most of the American aircraft industry had long since ceased building with wood. The most influential American Mosquito exponent was Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, the president’s son, who had flown a Mk.IV on reconnaissance in North Africa. By the time the Americans saw potential in a fighter-bomber that was both faster and longer-legged than their P-38, production at DHC, the North American source, was falling far behind schedule. Lee Murray returned from Hatfield in November 1942, this time to stay.

Garratt was able, nevertheless, to address an upbeat message at 1942’s year-end to “the DH Family,” as he habitually referred to the company, reporting that during the past year “we have produced 362 Ansons, 550 Tiger Moths, overhauled 119 aircraft and 209 engines; all of this on top of the development work on the Mosquito.”8 That same December, though, only four DHC-built Mosquitoes took to the air.

The problems were not entirely of DHC’s or Garratt’s making. Twice batches of drawings documenting Mosquito variants were lost at sea. Parts from England were being used to substitute for non-arrivals from subcontractors; when Boeing of Canada was late with horizontal stabilizers, or tailplanes, John Slaughter at Downsview built a couple of sets to keep the project moving. Although the original contract with Britain’s Ministry of Aircraft Production called for Mk.XX bombers, the contract was altered to include fighter-bombers, with six-gun noses and different windshields, among other changes. Downsview was also required to engineer its own dual-control trainer version. Then yet another change in the order occurred: aircraft on the line were to be converted as F-8 USAAF recon machines. (Only forty F-8s were ever delivered.) By mid-April 1943 only a dozen Mosquitoes had been produced, with fourteen more on the line.

The aspect of the Mosquito production gap that was unquestionably internal was the issue of who would run a single production line amalgamated from the Tiger Moth (Plant One, under Bill Calder and Frank Warren) and Anson (Plant Two, under George Burlison), with Dick Moffett as overall production manager. Harry Povey’s status put him in charge of “all production departments,” but neither Moffett nor Burlison approved of his production methods—in particular, the wood jigs that wing man Bob McIntyre of Massey-Harris had already refused to work with.9

Meanwhile, the demand for Mosquitoes grew, Hotson notes, “daily.” Ottawa was becoming concerned. Ralph P. Bell was a dollar-a-year man installed as Director-General of the Department of Munitions and Supply on whose desk the buck for aircraft production in Canada stopped.

Bell sent his assistant to look the operation over and—surprise!—found three different men claiming to be in charge of production. In reply, the DHC board of directors expressed its confidence in Garratt’s management. Bell told the directors he was holding them esponsible for the production holdups.

Two weeks later, lawyer J. Grant Glassco, a government-appointed director of DHC since early 1940, reported his assessment of DHC’S board to Bell. The two men went to see C.D. Howe, Minister of Munitions. Howe, the most powerful man in Canada at the time, appointed Glassco controller of de Havilland Canada by a secret order-in-council June 8, 1943.10 Phil Garratt was out.

Howe brought in as DHC works manager a thin, intense ramrod from his home riding of Fort William, Bill Stewardson. Stewardson “just lived, ate and slept aircraft production.”11 He had spent six years with Canadian Car and Foundry at the Lakehead, most of that time as shop superintendent on CCF’s licensed Hawker Hurricane production program. Soon after, Dick Moffett and George Burlison resigned to take other positions in the war effort. That October, Harry Povey was asked to return to England.

It took until the fall of 1943 before Downsview’s subcontractors other than Massey-Harris began to produce reliably. The events of that year were hard on morale, and a series of bitterly-fought elections brought the United Auto Workers into the company as bargaining agents. During December 1943, Mosquito production hit twenty per month for the first time.

So popular was Phil Garratt with DHC’S oldtimers that his departure was not announced to the workers for nearly a year. In the May-June 1944 issue of The de Havilland Mosquito, which appeared ten months after he was replaced by Grant Glassco, an item appeared on the second-last page headlined “CHANGE IN MANAGEMENT.” That same month of June 1944 Mosquito production was up to fifty-one, the figure Garratt had agreed to be turning out at the beginning of 1943.