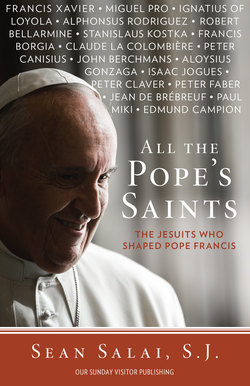

Читать книгу All the Pope's Saints - Sean Salai S.J. - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Trust

The only really effective apologia for Christianity comes down to two arguments, namely, the saints the Church has produced and the art which has grown in her womb.

— Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI)

Sometimes I don’t feel very close to God, but I feel close to the saints who are close to him.

For many dedicated Christians, even Jesuits like me, God can feel abstract and distant at times. Whether we’re talking about the Father, Son, or Holy Spirit, it doesn’t matter. Because I can’t see or touch the Triune God directly, it can be hard for me to sense his presence at certain moments in my life even if I know on an intellectual level that he’s there.

All sorts of things can block my relationship with God and keep me from bringing my messy life to him. At times, I may keep God at arm’s length simply because I don’t want him to see the ugly or broken parts of my soul. Or I may shut him out because I’ve suffered something awful, preventable or not, that makes me doubt the reality of his goodness.

But even when I don’t find it easy to talk with God, I often find it easy to talk with one of his saints, whose deeds and words invariably steer my heart gently back to him. By the example of their trust in God, the saints strengthen my ability to open up to him in trust when nothing else seems to be working.

As high school theology students know, the English word “saint” comes from the Latin sanctus for “holy,” which in turn comes from the Greek hagios for “holy ones.” It occurs in Scripture several times, including the opening address of Paul to the “holy ones” (saints) in Corinth. In this sense, saints include not only all those who are in heaven — whether recognized by the Catholic Church officially or not — but also those on earth who are already leading holy lives.

To become an official saint through the canonization process of the Roman Catholic Church, you have to be dead first. You must die with a reputation for holiness, having lived a life that brought many people around you closer to God. People might then begin praying to you, saving parts of your clothing or body as relics, and telling others about you. Eventually, some people might make formal petition to the local bishop, who would then decide whether to begin the lengthy investigation that could eventually result in you being proclaimed a saint.

The Roman Catholic Church has designated certain canonized saints as “patron saints” with a special connection to various professions, illnesses, nations, and so forth. We pray to these patron saints for certain things in those contexts. For example, St. Joseph was a carpenter, so carpenters and others might pray to him before working with wood. St. Patrick brought the faith to Ireland, so the Irish might invoke him on behalf of their nation.

We also have our individual patron saints. If a boy was baptized Timothy after St. Timothy, then he might pray in a special way to this first-century evangelist and bishop of Ephesus who traveled with St. Paul of Tarsus. The same would be true of a girl baptized Mary, who might pray to the Mother of God for help in doing God’s will in a difficult situation.

Patron Saints

You can learn a lot about Catholics by the patron saints each one of us adopts.

Upon being elected Vicar of Christ in 2013, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, S.J., chose St. Francis of Assisi as his papal namesake after a fellow cardinal asked him to “remember the poor.” Deeply moved by this request, the future Pope Francis recalled the image of the holy beggar who founded the Franciscans and felt drawn to choose him as the patron saint of his papacy. Like St. Ignatius on his sickbed, the world’s first Jesuit pope felt especially close to this saint of the poor.

Many of us have more than one saint in our names. My own name is Sean Michael Joseph Ignatius Salai, S.J. Not to the U.S. government, of course, for whom I am merely Sean Michael Salai. But within the Catholic Church, in which I’ve chosen two of these names for myself, that’s my full name.

Sean, my first name, is an Irish form of John. I received it as a baby without any religious significance or Irish ancestry, but I’ve since adopted St. John the Evangelist as my name saint and December 27 — his feast day — as my onomastico or “name day” to celebrate in a special way. In this case, I might have picked another St. John, but I really like John’s gospel!

I also received my middle name, Michael, without any particular religious significance. But I associate it with St. Michael the Archangel, the warrior spirit who leads God’s army of good angels against Satan’s army of rebellious angels (demons) in the Book of Revelation. When I struggle with the demons of my life, I recite the Prayer to St. Michael the Archangel:

St. Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle.

Be our protection against the wickedness and snares of

the Devil.

May God rebuke him, we humbly pray,

and do thou, O Prince of the heavenly hosts,

by the divine power of God,

cast into hell Satan, and all the evil spirits,

who prowl about the world seeking the ruin of souls. Amen.

This is a prayer of minor exorcism, offering protection (not deliverance from demonic possession) against the influence of evil spirits in our lives, whether they are spirits of temptation and addiction or of compulsion and oppression. At times of internal struggle, no matter how agonizing, I find comfort in reciting these words. As an angel, St. Michael is a pure spirit (he never had a physical body) rather than a human being, so he’s not exactly cut from the same cloth as me, but I pray to him when I need courage and help in difficult battles. The image of Michael’s winged figure clad in armor and stabbing a demon in the head with his sword, seen in many Catholic statues and paintings, can feel mighty comforting when I want God to stab my selfishness and hardness of heart in the head.

St. Michael casts out the “accuser of our brothers,” as the Book of Revelation calls Lucifer (12:10), who condemns us before God as worthy of eternal damnation — this Satan who whispers our sins into our ears to tempt us to despair. Michael drives out the demons of this accuser who tempt us to doubt God’s love for us, to doubt our own goodness, and to doubt the evidence of our religious experience and of all created things that testify to God’s power. Alcoholics and addicts, policemen and murderers alike, have called on St. Michael for help in times of struggle. I have called on him myself in prison ministry, working from 2014 to 2017 in the Catholic chaplaincy at San Quentin state prison in California, where inmates experience a powerful sense of demonic evil.

My third name, Joseph, is my “confirmation name,” a custom from some parts of Europe that has found a home throughout much of the United States. The idea is simple: You pick a saint you like and make his name part of your own when you receive the sacrament of confirmation. It’s pretty cool to pick a name for yourself, and often the bishop or priest even uses this name, rather than your birth name, when confirming you.

During my junior year (2001–2002) at all-male Wabash College in Indiana, I chose St. Joseph for my confirmation name after having some trouble deciding whom to pick. Not having grown up Catholic, I wasn’t sure how to discern what saint inspired me the most. When I asked our local pastor for advice, he just shrugged and said: “When I was a kid, every Catholic boy picked Joseph.” For him, the husband of Mary covered all bases, as St. Joseph is the patron saint of everything from husbands and workers to priests and the universal Church.

When I reflected on St. Joseph in prayer after my confirmation, I found myself admiring his trust in the infancy narrative of Matthew’s Gospel, where he takes Mary into his home and follows God silently despite his initial uncertainty. Since I figured I might have a family of my own one day, Joseph seemed like a good patron saint for me, as he was the patron of fathers too. For a year or two, I prayed to him with a little chaplet (corded rope with medal) and prayer that a friend gave me as a confirmation gift. I was also happy that Joseph was the patron saint of workers, as I certainly hoped to find a job after college!

Five years after my confirmation, when God called me to the priesthood instead of marriage, I had the chance to pick another saint’s name for my first perpetual vows in the Society of Jesus. Unlike some monastic religious orders where men and women replace their first name with a saint’s name, like “Rebecca” becoming “Sister Mary Robert,” I was not required to replace “Sean” with another name like “Aloysius” (Thank God!). But I followed the Jesuit option of choosing a devotional vow name, picking “Ignatius” in honor of our religious founder.

Jesuit Vows

During my two years of Jesuit novitiate from 2005 to 2007, I grew to admire St. Ignatius of Loyola for the depth of his relationship with God and for the life story in his autobiography, which moved me to tears and struck a deep chord in my heart. Like St. Ignatius, I felt God’s grace had led my life in a different direction than I originally planned, guiding me each step of the way to a deeper trust in the divine will.

On August 15, 2007, the Solemnity of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, I ended my two-year Jesuit novitiate by professing my first perpetual vows in the house chapel at St. Charles College in Grand Coteau, Louisiana:

Almighty and eternal God,

I, Sean Michael Joseph Ignatius Salai,

understand how unworthy I am in your divine sight.

Yet I am strengthened by your infinite compassion

and mercy,

and I am moved by the desire to serve you.

I vow to your divine majesty, before the most holy Virgin

Mary and the entire heavenly court, perpetual poverty,

chastity, and obedience in the Society of Jesus.

I promise that I will enter this same Society to spend

my life in it forever.

I understand all these things according to the

Constitutions of the Society of Jesus.

Therefore, by your boundless goodness and mercy

and through the blood of Jesus Christ,

I humbly ask that you judge this total commitment

of myself acceptable;

and, as you have freely given me the desire to make

this offering,

so also may you give me the abundant grace

to fulfill it.

St. Charles College, Grand Coteau, Louisiana,

August 15, 2007

Pope Francis, whose behavior as Holy Father continues to manifest the radical trust of a Jesuit’s lifelong commitment to God, took these same vows on March 12, 1960, and they sustained him up to his final profession of vows following ordination to the priesthood. They are the same first vows that every Jesuit has professed in various languages since the time of St. Ignatius, whose name now forms part of my own.

All of the saints in my name are part of my life’s story. I know them through their relics and writings, through biographies and films like Paolo Dy’s 2016 movie Ignatius of Loyola, and through my experiences of reflecting on the images of their lives in prayer. And if Pope Benedict XVI is right that the best arguments for Catholicism are its saints and the art it has produced, then the artwork depicting my “name saints” manifests God’s love to me in a unique way. In my room, as I write these words, hanging on the wall above my bed are the following icons: St. John the Evangelist, St. Michael the Archangel, St. Joseph, St. Ignatius of Loyola, and Our Lady of the Assumption. Each image has a distinctive iconography or set of artistic features identifying that saint, such as St. Joseph holding the baby Jesus or Mary rising from earth into heaven.

In addition to my icon of Mary, I have a large icon of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, an image dear to our religious order that bears his name. And I have a framed portrait of Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pope who, like many others and me, got to know the great Jesuit saints as he underwent our infamously long training program (it took him eleven years; twelve years for me) in preparation for ordination to the priesthood.

When my life feels like a failure, when I struggle to find God, and when nobody is nearby to talk with me about it, I can always look at these icons and talk with these saints. Their images pull me out of myself and remind me that I am never alone.

Surrendering to God

To live my vocation as a Jesuit, in this day and age, requires a lot of trust. At age twenty-five, I left a career as a newspaper reporter behind, selling a house and giving away a car to enter the Society of Jesus. But in the course of my formation for the priesthood from 2005 to 2017, it helped that I was surrounded by peers who were all making the same commitment, aging and struggling together with me as we grew into our Jesuit lives and priestly vocations.

It also helped that I had my patron saints, both Jesuit and non-Jesuit, to help me grow closer to God in moments of struggle.

On his first All Saints’ Day as supreme pontiff, Pope Francis put his finger on what makes the saints so accessible in drawing us to God:

The Saints are not supermen, nor were they born perfect. They are like us, like each one of us. They are people who, before reaching the glory of heaven, lived normal lives with joys and sorrows, struggles and hopes. What changed their lives? When they recognized God’s love, they followed it with all their heart without reserve or hypocrisy. They spent their lives serving others, they endured suffering and adversity without hatred and responded to evil with good, spreading joy and peace.

This is the life of a Saint. Saints are people who for love of God did not put conditions on him in their life; they were not hypocrites; they spent their lives at the service of others. They suffered much adversity but without hate.

(Angelus address, Solemnity of All Saints, November 1, 2013)

The saints lead all of us to God through their example of holiness. We may not always believe in God very strongly, but the love of his saints feels hard to ignore. If we believe in the reality of their love for God and neighbor, visible in the virtues of their lives, it gets easier for us to believe in God’s love as the cause of theirs. As St. Ignatius says, when we don’t feel any desire to get closer to God, we can at least express a desire for the desire.

Even as a Jesuit, there are times in my prayer when communication dries up and I have trouble visualizing God. At these moments, the Father seems to be away in the sky somewhere, sustaining creation. The Spirit appears to be in my heart, inspiring my religious experiences in a way hidden to me. And Jesus, whom outside of prayer I mostly know from the Bible, where his appearance is not described, and from images painted centuries after his death, is “always” with me somehow in a way that often seems vague.

Even when God feels distant or absent, though, I am able to talk with his friends. The saints lived in time and space, like Jesus, but they left clearer human traces in this world than he did. We have their bodies and relics, their personal effects and baptismal records, copies of their high school report cards and writings, and the testimonies of their friends. They lived ordinary lives like I am doing, without rising from the grave or ascending to heaven, and that makes them feel a little closer to my own human reality.

Many of God’s friends live among us. They are the saints-to-be in my life who remind me of his presence and love. They are the people close to me in daily life, doing their best to get by in this world. Manifesting God’s hands and heart and voice on earth, they make the faith come alive.

All of the saints pray for me, including the long black line of Jesuit saints beginning with Ignatius as well as the saints whose names form part of my own name: Ignatius, John the Evangelist, Joseph, Michael the Archangel, and Mary (Our Lady of the Assumption). All of these witnesses to faith, living and dead, have helped me entrust the messiness of my life to God in prayer. Just as we have different friends for different areas of our lives, there is a different saint for each virtue I desire and for each issue I struggle to bring before God.

The First Jesuit Saints

St. Ignatius had his own small circle of friends who inspired him and were inspired by him. As he studied for a master’s degree in philosophy at the University of Paris following his conversion, Ignatius guided his two young college roommates to greater spiritual freedom by directing them in the Spiritual Exercises. Both of these men, Peter Faber (also known as Pierre Favre) and Francis Xavier, eventually joined him on the list of canonized saints.

St. Peter Faber (1506–1546), a pious Frenchman from rural Savoy who was studying for the priesthood when he met St. Ignatius, was the first recruit for what became the Society of Jesus. Scrupulous and deeply spiritual, he learned to trust in God’s merciful love for him through prayer, becoming the first acknowledged master of the Spiritual Exercises. Ignatius, recalling his own scrupulosity, led Faber into a deep awareness of God’s love for him as a sinner.

Pope Francis canonized Faber, a personal role model in his life, as a saint in 2014. The pope knew that a peaceful and free surrender to God’s will in discernment marked Faber as much as it did Ignatius. In this brief prayer, Faber expresses a trusting desire for God to lead his life:

Show, O Lord, Thy ways to me,

and teach me Thy paths.

Direct me in Thy truth, and teach me;

for Thou art God my Savior.

For St. Peter Faber, knowing Jesus as his savior was reason enough to trust him, no matter how many unexpected sufferings life brought him. Indeed, when he took ill and died at forty while preparing to attend the Council of Trent in 1546, he passed away in deep tranquility.

St. Francis Xavier (1506–1552), a hedonistic young nobleman from the opposite political fence of Spain from St. Ignatius, was a harder sell than Faber because he was so stubbornly self-seeking. In many ways, Xavier was a throwback to Ignatius’s younger days, and it was precisely this strong will that gave Loyola such high hopes for him.

Ignatius liked Xavier so much that he wouldn’t leave him alone, hassling him daily with the singsong refrain: “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world and lose his soul?” Finally, during a nocturnal outing, Xavier was scared straight by catching sight of a syphilitic acquaintance dying in the streets. He came to his senses and began to follow the spiritual guidance of Ignatius with enthusiasm, making the Exercises and pledging to do great things.

True to his word, Xavier became the order’s first great missionary when Ignatius chose him to replace a Jesuit who couldn’t travel to the missions in India. When St. Ignatius asked him to go, Xavier famously responded without hesitation: “Here I am, send me.” And St. Francis Xavier left for India knowing he would never again see home, St. Ignatius, or any of his loved ones.

More a man of action than of words, Xavier traveled all over Asia, exploring peoples and places largely unknown to Europeans at the time. He soon ended up in Japan, where Portuguese traders had only recently made contact, pushed farther inland than any European had done up to that point, and established the first Christian missions in a number of fishing villages.

Hearing in Japan of the great Chinese people, Xavier spent the rest of his short life trying to get into that country. But while awaiting a boat to the mainland in 1552, he took ill and died off the southern coast of China on the island of Sancian.

As Xavier’s body retraced his missionary steps backward, being carried in public funeral processions at each stop, the crowds hailed him as a saint, and in India one devout Catholic woman bit off his toe to keep as a relic. The Jesuits, of course, made her give it back.

Like St. Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew, summoned by the angel to flee into Egypt with the Holy Family, St. Francis Xavier placed himself entirely in God’s hands, walking the fields of Asia with a profound sense of trust in God’s protection. There was nobody to translate for him, feed him, or help him understand the cultures he met. He had only his faith in God to drive him.

Recognized later as the greatest missionary since St. Paul, and honored by Christians of all backgrounds, Xavier achieved incredible results because he surrendered to God with a deep intensity known only to the saints. In Asia, he spent every ounce of his energy teaching Catholicism to children and simple persons, reporting so many baptisms at one point that he didn’t even have time to recite his breviary. Isolated by cultural differences and by an unreliable mail system from Jesuit headquarters in Rome, he sewed the few letters he received from St. Ignatius into his cassock, keeping them over his heart to feel their friendship more deeply.

St. Francis Xavier’s radical trust in God appears especially striking in the Act of Contrition he wrote for himself:

My God, I love you above all things,

and I hate and detest with my whole soul the sins

by which I have offended you,

because they are displeasing in your sight,

who are supremely good and worthy to be loved.

I acknowledge that I should love you

with a love beyond all others,

and that I should try to prove this love to you.