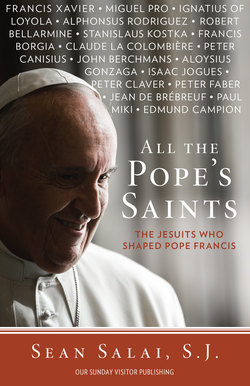

Читать книгу All the Pope's Saints - Sean Salai S.J. - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

Immersed in the World

And may we be accompanied on our way by the fatherly intercession of St. Ignatius and of all the Jesuit Saints who continue to teach us to do all things, with humility, ad maiorem Dei gloriam, for the greater glory of our Lord God.

— Pope Francis, homily on the feast of St. Ignatius of Loyola, July 31, 2013

Desperate and unemployed, the wild-eyed young Spaniard fell to his knees in a cave by the Cardoner River, tears streaming down his face as he begged Jesus to give him a sign.

Convinced by a recent career-ending injury that God was punishing him for years of uncaring selfishness, the young man whipped himself on the back repeatedly, returning to the cave each day for ten months from a flophouse in Manresa where he was staying. His fingernails grew long and nasty, his hair dirty and flowing, but he didn’t care — his life had fallen apart.

Fasting to an extreme, the guilt-ridden man ate nothing for days on end, nearly starving himself to death despite the protests of his confessor. Resisting even the smallest comforts, he went barefoot in all seasons. Despite his beard and rags, he wasn’t much older than thirty, and he was obsessed with rethinking where his life was headed.

Perhaps if he punished himself enough, the young man thought, it would please his angry image of God and put things back the way they were before the injury that nearly killed him.

Only a year earlier, this same man had been physically fit and happily employed, leading a pleasure-seeking life without a care in the world. The privileged youngest child of a large well-off family, he had never really known what it meant to suffer or to struggle, and he had spent much of his life avoiding people who did. As a worldly soldier in his twenties, he thought he had figured out the recipe for happiness: Take whatever you want from others to satisfy your appetites — just don’t get caught. With this attitude, it hadn’t taken him long to become a womanizer, a gambler, and a violent brawler.

This way of life had ended in a battle at the city of Pamplona, where an enemy shell shattered his leg. After the injury terminated his military command and left him with a permanent limp, resulting in surgeries that almost killed him, the young captain had spent several months in bed at his family home, slowly recovering his strength and ability to walk. Filled with shame and confusion on his sickbed, he read the life of Christ and the lives of the saints, struggling to understand what God was saying to him through the recent events of his life.

Several questions now haunted him. What did he really want out of life? Why had God let this happen to him? And where would he be in five or ten years if he went back to his old self-seeking habits?

There didn’t seem to be any rational answers, let alone easy ones. The young man hadn’t spent much of his life thinking about God before Pamplona, but the battle wound and religious books suddenly made his childhood Catholicism feel very meaningful to him. Convinced that his injury was some kind of divine punishment or message, he took a long time to realize God was speaking more through his sufferings than through the vain self-flatteries of his mind.

After getting back on his feet and leaving the care of his family, the young man resigned his military commission, even though his superior insisted he could be promoted to a more comfortable and limited role. Refusing his family’s help and sending their money back, he went to the mountaintop Benedictine abbey of Montserrat to renounce his old life and then made his way to the cave at Manresa. At Montserrat he traded his clothing for rags and became a street person, carrying a walking staff as he proceeded to beg from town to town, sleeping under the open sky and in homeless shelters.

In the riverside cave at Manresa, the young man spent several hours a day contemplating the Gospels and the lives of the saints, imagining himself present with Jesus and with holy men like St. Francis of Assisi and St. Dominic. As he prayed in this way with Jesus and with the Lord’s saints, different thoughts and feelings came up within him, giving him the signs he sought. Gradually, he discerned that God was inviting him to help others rather than to punish his own body, and he left the cave to begin a new life as a Christian street preacher. Although his family was embarrassed by his behavior, he felt certain for the first time in his life that God was not.

An Unlikely Saint

To his family and friends, St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) was the most unlikely person in the world to become a canonized Catholic saint, let alone establish a worldwide religious order. But he is the same young man I have just been talking about — a professional soldier whose battlefield encounter with God’s grace transformed him from a self-centered playboy into a beggar, a priest, and finally the founder of a religious order that exists to this day: the Jesuits.

While Ignatius may not have been as flagrant a sinner as St. Augustine or St. Paul, his conversion was just as dramatic to those who knew him best. As a symbol of this change in life, he even changed his first name from Íñigo to Ignatius in honor of St. Ignatius of Antioch (A.D. c. 35 – c. 108), the early bishop and Church father who was martyred by being fed to wild beasts. But even though he eventually started the Jesuit order (Society of Jesus) to which Pope Francis, many others, and I belong, St. Ignatius of Loyola spent nearly half of his sixty-five years on earth as the sort of young man respectable people crossed the street to avoid.

Born into the minor nobility as Íñigo López de Loyola in the Basque region of Spain, the youngest of thirteen children, Ignatius spent the first three decades of his life as a self-appointed tough guy who rarely darkened the doorway of a church. Professing a basic belief in God and knowledge of popular pieties, he was what we might today call a “cultural Catholic.” He was “spiritual but not religious.”

For the young St. Ignatius, God was best kept at a distance, locked up somewhere in a family strongbox marked “open in case of emergency.” As long as God didn’t ask anything of him while he sought his pleasures in life, Íñigo didn’t ask anything of God, and he liked it that way. When life was good, he took God for granted and prayed on his own instead of going to church, because he thought he didn’t need anyone other than himself. He never considered what might happen if life got difficult.

After reaching maturity, Ignatius joined the military service of a duke, hoping to find personal glory in Spain’s expanding global empire during an age of exploration. A self-styled hidalgo, or member of the Spanish nobility, he wore the finest clothing: tight-fitting hose, buckled leather boots, a ruffled shirt, and a gaudy hat with feather on top. This gaudy “look at me” outfit came complete with a buckler, dagger, and sword.

The young Ignatius was Catholic in the sense that many sixteenth-century Spaniards were Catholic, knowing his basic prayers and receiving Communion twice a year. But his faith was completely externalized, being as far from touching his heart as his behavior was from a meaningful relationship with Jesus Christ. His real passions involved satisfying his own wild appetites for life, dancing well and talking big, and seeking to impress the ladies at court and in the taverns. At one point, he was jailed briefly for beating up a priest who owed his family some money, but was released on a technicality.

While Ignatius had great desires for worldly success, his romanticized fantasies about life were turned inward, and it would be an understatement to say he was self-obsessed. His awareness of the world started and ended with himself: He was the writer, director, and star of his own heroic epic. But his life, like so many of our lives today, did not turn out the way he scripted it.

By all accounts, he should not have survived his youth, let alone become a saint to whom Jesuit schoolboys would pray before high school football games some five hundred years later. Ignatius was ill-tempered and unstable, a self-styled soldier of fortune who stared people down in public, looking for any excuse to start a fight. Modern historians believe he fathered at least one child out of wedlock, but later generations of Jesuits seem to have scrubbed the records, and Ignatius himself remains intentionally vague about his early life in his extant writings.

It hardly matters. Like too many of us since the dawn of human history, it’s enough to know that St. Ignatius before his conversion was a man who took what he wanted from life without giving a thought to the suffering of others. He was a man who lived by the illusion that he, not God, was in control of his world and his life.

As Ignatius himself summarized his youth in a third-person autobiography, he was a young man “given over to the vanities of the world, and took a special delight in the exercise of arms, with a great and vain desire of winning glory” (Autobiography of St. Ignatius of Loyola, English translation by Fr. William J. Young, S.J.). But in a gunshot that echoed throughout history, all of that changed when the cannonball smashed his leg during a French military siege at the walled city of Pamplona in 1521.

After barely surviving a series of barbaric surgeries that led him to receive the Last Rites, Ignatius reconsidered the direction of his life on his sickbed, reading the life of Christ and the lives of the saints during his long medical rehab only because there were literally no other books in the family castle to keep his restless mind occupied. Throughout his suffering, and in the pages of these books, he learned compassion and began to open his heart to God’s healing.

These books told him about the selfless love of Jesus Christ, but also about the adventures of great saints like Dominic and Francis of Assisi. It was because God’s love pierced his broken heart through their pages that Ignatius gradually became a penitent, a pilgrim to the Holy Land, and finally a priest who founded the Society of Jesus under Pope Paul III in 1540. Through its missionary outreach, this Society has gone on to establish a vast global network of schools for laypeople, essentially founding modern education as we know it today.

Yet the biggest legacy St. Ignatius left to the world, as far as he was concerned, was the example of his own life and spiritual journey as a path to God. Jesus Christ met Ignatius in his brokenness with mercy and transformed him into a new man. His life would never be the same.

One story in particular captures for me how dramatically God changed the direction of St. Ignatius’s life. Several years after the cannonball wound of Pamplona, a man who had known Ignatius in his younger days happened to encounter the saint begging in the streets. Ignatius’s changed attitude shook him deeply. Unable to believe the holy beggar in front of him and the violent young soldier he had once known were the same person, the distinguished gentleman burst into tears.

Ignatian Spirituality

Today we continue to reap the fruits of St. Ignatius’s gift of Ignatian spirituality to the Catholic Church, a way of finding God in the world rather than in withdrawing from it. Through the directed retreat movement inspired by Ignatius, who wrote the Spiritual Exercises (based on notes he jotted down about his experiences in the cave at Manresa) as a manual for retreat directors, we Jesuits have spread this practical spirituality to laypeople and clergy of all Christian backgrounds worldwide for nearly five hundred years.

Ignatian spirituality, as we Jesuits use the term, refers broadly to a particular way of relating to God in prayer, a way rooted in the experiences of Ignatius and the many Jesuit saints who have followed him. It invites people to embrace a Christ-centered vision of reality rather than a self-centered perspective that leads to anxiety and despair. The question that drives an Ignatian worldview isn’t “how do I see God?” but “how does God see me?” How does God see my family, friends, and the world around me? What is God doing in the concrete circumstances of my life?

The goal of this kind of reflection is not intellectual knowledge or insight, but “felt knowledge” that burns itself into the heart like a red-hot iron, forging a deep personal bond. Ignatian prayer is like sitting wordlessly before a sunset, savoring what we notice about its presence, and applying it to ourselves in conversation with God; it’s not like thinking about the sunset and talking to ourselves about it. It invites us to encounter the living presence of Jesus Christ in prayer, not to remain trapped in our own thoughts. Can I sit with an image of God from Scripture and notice where it stirs me? Can I talk to God about what’s really going on inside of me without presenting only my “good” or idealized side to him?

Many ordinary people have valued the Ignatian focus on discerning God’s presence in our religious experiences rather than in the clouds of theological abstraction. Despite the reputation of Jesuits for being over-educated, St. Ignatius was a practical mystic whose approach to the spiritual life was based on encountering God in our everyday experiences, not on fleeing from them into intellectual fortresses built on the sand of our mental constructs. Ignatius invites us to bring whatever is happening in our lives to prayer, ask God for what we want, and listen to how the Lord responds.

Following his conversion, St. Ignatius embraced Jesus Christ’s call to hate the world, but not in the sense that he rejected God’s creation as inherently evil, splitting earth and heaven into two unrelated realities. For St. Ignatius, the Christian who “hates his life in this world” (Jn 12:25) turns away from selfishness, but not from the messiness of life. So “the world” in this negative sense refers to God’s creation as we’ve corrupted it through our selfish ways rather than to God’s creation in and of itself. If Ignatius knew anything from his own experiences, it was the difference between human selfishness and self-giving love.

Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J. (1881–1955), the French Jesuit geologist and mystic, expresses with particular clarity the Ignatian invitation to embrace God’s creation as good:

In so doing, [the disciple] does not believe he is transgressing the Gospel precept to hate and contemn the world. He does, indeed, despise the world and trample it under foot — but the world that is cultivated for its own sake, the world closed in on itself, the world of pleasure, the damned portion of the world that falls back and worships itself.

(“Mastery of the World and the Kingdom of God” in Writings in Time of War, 83–91)

To live in the world without sensing God in it damns us. While St. Ignatius rejected this sinful sense of worldliness in his own life, he was a practical mystic who nevertheless loved all that is good and beautiful in human experience. He rejected “the world” as corrupted by human sin, but he also loved “the world” as God creates, sustains, and calls it — including all of us — to be.

The need to discern prayerfully between creation’s goodness as redeemed by the Trinity’s saving action (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit working together in collaboration with us for our good) and its distortion by sin continues to inform the spiritual vocabulary of Jesuits today. Pope Francis, the most prominent Jesuit of our time, evokes this Ignatian view of “the world” whenever he preaches about the either-or choice between God and mammon, service and consumerism. He described “the world” in its negative sense in his speech to the poor at Assisi, Italy, lamenting the deaths of more than 360 refugees in a shipwreck:

Of what must the Church divest herself? Today she must strip herself of a very grave danger, which threatens every person in the Church, everyone: the danger of worldliness. The Christian cannot coexist with the spirit of the world, with the worldliness that leads us to vanity, to arrogance, to pride. And this is an idol; it is not God. It is an idol! And idolatry is the gravest of sins!

(Speech in the Room of Renunciation in the Archbishop’s Residence, October 4, 2013)

If the pope calls us to reject worldliness, he also calls us to embrace the spirit of God that lies at the heart of Ignatian spirituality. We find that spirit rooted in the virtue of humility, the good habit of seeing ourselves and the realities around us through Christ’s eyes rather than through the lens of self-centered distortions. Later in this same speech on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, the Holy Father distinguished this Christlike humility that forms the hinge of all saintly virtues from the worldly self-interest that makes us oblivious to the suffering of others:

And Jesus made himself a servant for our sake, and the spirit of the world has nothing to do with this. Today I am here with you. Many of you have been stripped by this callous world that offers no work, no help. To this world it doesn’t matter that there are children dying of hunger; it doesn’t matter if many families have nothing to eat, do not have the dignity of bringing bread home; it doesn’t matter that many people are forced to flee slavery, hunger, and flee in search of freedom. With how much pain, how often don’t we see that they meet death, as in Lampedusa; today is a day of tears! The spirit of the world causes these things.

It is unthinkable that a Christian — a true Christian — be it a priest, a sister, a bishop, a cardinal, or a pope, would want to go down this path of worldliness, which is a homicidal attitude. Spiritual worldliness kills! It kills the soul! It kills the person! It kills the Church!

This radical invitation to shift our focus from self-centered to Christ-centered living has not only marked the spirituality of St. Ignatius and Pope Francis, but has influenced many centuries of Christian believers down to the present. Thanks to the publicity of the global media, it has become particularly visible in the papacy of Francis. Yet over the past five centuries, we can see the characteristic humility of this spirituality at work in countless Jesuit saints and others throughout the world, from the famous to the forgotten.

St. Ignatius and Pope Francis

In a homily on the feast of St. Ignatius Loyola at the Gesu, the Jesuit mother church in Rome, Pope Francis emphasized three hallmarks of Ignatian humility: putting Christ and the Catholic Church at the center; letting ourselves be won over by him in order to serve; and feeling ashamed of our shortcomings and sins so as to be humble in God’s eyes and in those of our brothers and sisters.

To help visualize what it means to de-center ourselves and put Jesus Christ at the center of our lives, Francis prayerfully contemplated in his homily the image of the “IHS” seal of the Society of Jesus. This monogram — typically surrounded by a sunburst and featuring the three nails from Christ’s crucifixion beneath it — adorns his own papal coat of arms:

Our Jesuit coat of arms is a monogram bearing the acronym of “Iesus Hominum Salvator” (IHS). Each one of you could say to me: we know that very well! But this coat of arms constantly reminds us of a reality we must never forget: the centrality of Christ, for each one of us and for the whole Society which St. Ignatius wanted to call, precisely, “of Jesus” to indicate its point of reference. Moreover, at the beginning of the Spiritual Exercises we also place ourselves before Our Lord Jesus Christ, our Creator and Savior (cf. EE, 6).

(Homily on the Feast of St. Ignatius of Loyola, Church of the Gesù, Rome, July 31, 2013)

All the great Jesuit saints, following Ignatius, strove to make Jesus Christ the commander-in-chief of their lives. The Holy Father, recognizing that true humility sees Jesus rather than ourselves at the center of our existence, wants all of us to do the same. Regarding his second point about surrendering oneself to Christ’s loving invitation, Francis noted how this humbling dynamic plays out in the conversion experiences of both St. Ignatius and St. Paul:

Let us look at the experience of St. Paul which was also the experience of St. Ignatius. In the Second Reading which we have just heard, the Apostle wrote: I press on toward the perfection of Christ, because “Christ Jesus has made me his own” (Phil 3:12). For Paul it happened on the road to Damascus, for Ignatius in the Loyola family home, but they have in common a fundamental point: they both let Christ make them his own. I seek Jesus, I serve Jesus because he sought me first, because I was won over by him: and this is the heart of our experience.

In his third point, the pope explores the Ignatian image of “healthy shame” for our sins, by which he means guilt as a natural and healthy response to our hurtful actions, as opposed to psychologically damaging self-hatred. Healthy shame works as a corrective to human egoism:

We should ask for the grace to be ashamed; shame that comes from the continuous conversation of mercy with him; shame that makes us blush before Jesus Christ; shame that attunes us to the heart of Christ who made himself sin for me; shame that harmonizes each heart through tears and accompanies us in the daily “sequela” of “my Lord.”

And this always brings us, as individuals and as the Society, to humility, to living this great virtue. Humility which every day makes us aware that it is not we who build the Kingdom of God but always the Lord’s grace which acts within us; a humility that spurs us to put our whole self not into serving ourselves or our own ideas, but into the service of Christ and of the Church, as clay vessels, fragile, inadequate and insufficient, yet which contain an immense treasure that we bear and communicate (cf. 2 Cor 4:7).

Following a Jesuit tradition, Pope Francis preaches “in threes.” Here he explores three aspects of humility in Ignatian spirituality: putting Christ at the center, surrendering to Christ’s loving service, and feeling healthy shame over sin. But he does not present these aspects as exhaustive of Ignatian spirituality. Instead, he develops them as points for meditation which he sees in the Mass readings for St. Ignatius Day — as images for prayer which strike him as applicable to our own lives. In addition to these points, there are many other virtues in Ignatian spirituality which inform the language of this pope and the way he relates to God.

Spirituality in Action

While many people have noticed the popularity of Pope Francis, few casual observers may realize that the Ignatian spirituality driving his papacy precedes him and will endure long after he is gone. It is the spirituality of St. Ignatius of Loyola that formed Francis, not Francis who formed Ignatian spirituality. If knowing someone’s family helps us to know that person, then we must understand Francis as a son of St. Ignatius to appreciate the sources of his spiritual fire, and we must look at how the Jesuit saints lived to fully grasp how Francis strives to live.

In this book, I will illustrate the world-focused (rather than worldly) Ignatian spirituality of Pope Francis through the stories of great Jesuit saints and their companions. St. Ignatius notes in his Spiritual Exercises that “love shows itself in deeds more than in words” (#230). It is likewise my goal in this book to show Ignatian spirituality in action more than just talk about it. Rather than send readers to encyclopedias to look up Jesuit terminology, or to a theological library for further study, I hope the lives of the saints covered in this book will speak for themselves, inspiring readers to grow in virtue and in relationship with the Holy Trinity. Because Ignatian spirituality is first and foremost about our experiences of God, not our theological insights, I want to share the experiences of Jesuit saints who have helped Pope Francis and others grow closer to the Lord.

Although Pope Francis embodies Ignatian spirituality on a very large stage due to the prominence of his office, there are many Jesuit saints and non-Jesuit saints (both men and women) who have lived this spirituality in a less visible way. The early Jesuits were scrupulous about promoting the canonization of our martyred or saintly members, as St. Ignatius encouraged his missionaries to always write two letters back to Rome — one with all the positive details for publicity purposes and one with all the problems for internal use. And the first Jesuits were forward-thinking in the way they carefully documented everything: When the Society of Jesus was suppressed in 1773, the Jesuit archives filled an entire building, while the Capuchin Franciscan archives barely occupied a single room!

Partly because we Jesuits are such zealous researchers and writers, the long black line of canonized Jesuit saints now stretches further than those of many other religious orders: There are currently about 350 Jesuit servants of God, venerables, blesseds, and saints in the various stages of canonization. And we observe many common virtues of Ignatian spirituality in the lives of these men, springing from the foundational quality of humility that Pope Francis spoke about. In the next chapters of this book, I will look at the following virtues in some of the most prominent Jesuit saints and their companions:

• Trust: Saints who surrendered themselves profoundly to God

• Openness: Saints who dreamed big, listened to God, and went outside the box

• Generosity: Saints who gave without counting the cost

• Simplicity: Saints who learned to have or not have things, insofar as it served God

• Dedication: Saints who followed Jesus even when things got tough

• Gratitude: Saints who saw everything, including themselves, as a gift from God

Finally, I will conclude the book with a reflection on the transformation we seek in reading the stories of these holy people, suggesting some takeaways from the lives of the Jesuit saints for our own spiritual lives.

Why does any of this matter? Well, as I hope to show, the Holy Spirit has given us Pope Francis not just for the present time, but for the future as well. He’s modeling a particular way of relating to God for all Christians as we progress in our journey through this life to the next. If some readers don’t care much for Pope Francis or for his way of speaking about Jesus, they may not like this book very much either, but I hope they will read it in the spirit in which I have written it: with an openness to considering those spiritual influences which have guided the life of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who we now know as Pope Francis.

Ignatian spirituality calls all of us — not just Jesuits or Catholics — to greater trust, openness, generosity, simplicity, dedication, and gratitude in our relationships with God as we journey through salvation history. Like the Jesuit saints who formed him spiritually, the example of Francis invites all of us to develop Christ-like habits in our lives.

The Gift of Ignatian Spirituality

Having given us a Year of Mercy, and nearing the end of what he foresees as a short papacy, Pope Francis will leave the Catholic Church with the ongoing gift of his Ignatian spirituality — a missionary perspective on discipleship that emphasizes passionate engagement with the world, calling upon Christians to value all that is beautiful and good in God’s creation while rejecting all that is selfish and distorted.

From St. Ignatius to Pope Francis himself, this is a spirituality lived by and for hardworking people trying to make it in the world, and it has helped many pilgrims in their life’s journey to God. Through the stories of Jesuit saints both famous and obscure, as well as the oft-unsung lives of the heroic men and women who collaborated with them on mission, I hope this book will challenge all Christians to follow Jesus with compassion and renewed energy.

The way Francis has lived out this spirituality, handed down to him by St. Ignatius and his brother Jesuits over the centuries, is distinctively bold and tender at the same time. Jesuit saints often inspire people with their intense fusion of the intellectual and the passionate, the sensitive and the bold. We sons of Ignatius value an integration of mind and heart that continues to attract people in our hectic world, calling all of us to an intelligent orthodoxy that’s all about tuning in to the broader culture with sympathy for what’s going on, rather than rejecting everything secular out of hand.

My book, then, strives to set the right tone and spirit for a deeper relationship with God. It’s about engaging the world in a positive way, but with our eyes wide open to painful realities. St. Ignatius wanted Christians to be immersed in the world, leading our lives boldly and getting our hands dirty. Like Pope Francis telling pastors to “smell like the sheep,” embracing the model of a “field hospital” church in which we all find solace, faith, and healing, St. Ignatius didn’t want fearful followers praying behind closed doors, safely isolated by creature comforts and clerical privileges from the struggles of ordinary people.

This missionary image of the Catholic Church is not unique to Pope Francis, but distinctive of the Society of Jesus in which he, many others, and I have vowed our lives to God. The message of St. Ignatius is that any person of good will, without reading long theological tomes or taking classes, can hear and speak to God. And the Jesuit saints can show us how to do it.

St. Ignatius of Loyola started his own life as a two-bit “man on the make,” seeing very little beyond the end of his nose. By his own telling, he should have died young in a gutter or a brawl, forgotten to history. But he changed the world and became a saint in the process because he woke up to God’s love in the nick of time. His story reminds us that Jesus Christ remains active in our world, waiting for us to let him draw us closer into his friendship. We need only to put him in the center, surrender to his invitation, and embrace our reality as loved sinners.

If St. Ignatius could do it, why can’t we?