Читать книгу Funhouse - Sergio Kokis - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

8

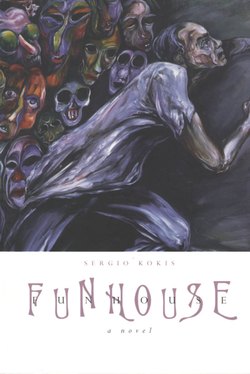

ОглавлениеHOW CURIOUS IT IS to think back to all those things, the finely detailed faces that have remained like scars in my mind, cut off from the ebb and flow of life. But when I look at my paintings, the process is reversed. I can return to the past. Scenes forgotten and events forever erased are reborn with all the clarity of a film. Even if the theme of the canvas seems separate from my own experience, it can still reveal and rekindle memory, and transport me back to the past.

There I come upon the faces of my childhood, the made-up women, the rigor mortis mouths of the dead, the colour and light of a particular place or moment. I had to create this huge complex of shadow and ink tracing in order to finally clear away the debris of long-buried memories. In the process, he who believed himself free finally came to see himself as nothing more than the creation of his predestination — like larva infected by the eggs of midges that believe they will become butterflies but are nothing more than nests and nourishment for graceless, colourless parasites.

Those are my feelings as I resuscitate the things I’d done my utmost to forget. The new identity I’d toiled so hard to acquire has turned into a trap. From now on I will gladly surrender to the role of bit player in a farce conceived in the eyes of a solitary child. All this effort just to return to the starting point. All these paintings just to return to the little boy I had hoped to lay to rest. The people around me hardly notice, so tough has my outer shell become, polished by the buffing of chance. My layers of masks have stratified, and my extremities are sharp. I’ve turned into a reptile of sorts, with a carapace of steely scales protecting a soft, vulnerable body.

Look at this blind soldier surrounded by cripples in a painting that seems to exhale toxic vapour — that’s how I re-en countered one of my classmates, the one who used to tell me how good girls smell. Or this canvas that I’d wanted to symbolize exile, yet which turned into a faithful representation of the drowned, draped by multicoloured garlands of seaweed. All these human machines — the marionettes, the disconnected mechanisms and dismembered dolls which I believed to be allegories of alienation — are nothing but street corpses, ghosts that have come back to tug at my legs in this cold land. My scarecrows are soldiers falling into rank; my agitator is one of the street vendors of contraband junk. My railway station scenes of immobilized crowds turn out to be the landscape of the public health clinic. The man falling before the firing squad is the figure of my father losing his footing on a makeshift scaffold. The women of the Mango district press against me, accompanied by made-up shrews, Holy Virgins with breasts exposed and the statue of St. Anthony surrounded by slashing hordes. The obese stroll nonchalantly among the emaciated with their covetous stares, while the impotent bourgeois stroke the flesh of young ladies seeking their future. The Creole mother and child that vaguely resembles a religious icon is really the young housemaid with her baby, pregnant once more, on a visit to my mother to beg for pardon.

Colour is even more misleading. I realize that the delicate pink-violet tone I applied under the eyes of a young girl was first given to me by the gums of a corpse left too long in the sun. Or that the pale green hue of a mulatto woman’s eyes belongs to the skin of a white woman who’d drowned. Do I delight in the effect of a sunset I’ve successfully completed? Immediately the ecchymotic pustules on a forgotten leg surge back into my consciousness to claim their rainbow colours. In truth, all the reds, yellows, greens and indigos were already there, and far more beautiful, in the sunlight. The tones reflected in the purplish face of a cardinal are identical to the ruddy tinge of an obscene drunkard from my childhood. His eyes, even his licentious grin perfectly match my cardinal’s. The emaciated ivory of a Christ is drawn directly from the pallor of Ambrosio the transvestite who would religiously evoke the vigour of the divine rod in the most scabrous terms. And the gleaming roundness of that death’s head behind a blue veil reminds me of the breast of a pretty young mother lowering her eyes as she unbuttons her blouse to nurse her child. Keeping track of my ideas is a near impossibility, especially late at night. The only way to calm the whirling waters, exacerbated by lengthy exposure to artificial light, is to drown them in alcohol. If I don’t, the flashes of light behind my closed eyes will not let me sleep.

Those flashes against a black sky seem to come from the past, when they mingled with the odour of sulfur and phosphorus. They are the fireworks displays of my childhood, so poor, yet awaited with such anticipation by my eyes thirsting for colour. Father loved the fireworks we would buy on St. John’s day in the little shacks that sprang up all over the city. The shacks themselves were painted in bright colours to tempt the eye and sharpen desire. He would always buy the least expensive, but with a concern for variety. He would light them, teaching me how to set off a multitude of scintillating explosions: sulfur and coppery greens, near-white magnesium yellows, cadmium pinks and purples as pale as the wrappers of expensive candies. I was so fascinated by the flames reflected in the eyes of people watching me that I risked getting burned. The white smoke of these magic matches acted as a soothing balm for my cough, as did tobacco, the moment I left the house. Exploding firecrackers added to the charm, along with the whining of skyrockets, the flowering of Roman candles and the vortex of sparking pinwheels. Then Papa would take us to see other fireworks displays, or watch people releasing rice-paper balloons that swayed to and fro as they climbed upward against the night sky. We were in no hurry. We weren’t supposed to go to sleep early. The winter solstice brought ceremonies that celebrated the moon, and that celebrated other, more secret things, that took place behind closed doors, which children were not to disturb. We sailed through the night in search of coloured lights. The same colours that still gleam in my studio. Suddenly my pipe seems to produce sulfur, and the painting on the easel turns into a sparkler. That fire was my first object of desire, one so intense it’s a wonder I didn’t turn into a pyromaniac.