Читать книгу Funhouse - Sergio Kokis - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеTHE MUGGY HEAT OF THOSE DAYS exists only in my memory. Here, flowers of frost coat the windows with a dense grey tracery that grows back as soon as it is scraped away. The intense cold of long Januarys. No snow. Streets of indeterminate colour, dirty-white ice patches, splotches of ochre rust and urine. Everything bears a patina of soot that smoothes over surfaces and dulls the edges of sidewalks. Long-fallen, leftover snow gleams dully, hardened, compacted, glossy. The light is deadened. Some of the thick slabs are deeply fissured, exposing their ferocious skeleton. The sky is the colour of primordial, oxidized lead, but nothing falls from it. The slanting sun that slices the world diagonally has made itself scarce this winter.

Seen from inside, everything looks frozen. But I know the wind is blowing. It is always blowing. Aside from the sporadic whisper of the radiators, the silence is complete.

So complete it takes on the form of a dull humming in my head. If I pay attention to it, the sound of tobacco burning in my cigarette crackles like a brush-fire. I am walled up in my basement apartment, protected by the foundations of the ice-encrusted house. It is as if the world no longer existed.

The mailman has come and gone. I saw him. Actually, I was waiting for him, waiting for him as always, just in case a letter arrived, so I won’t be startled. But he delivers nothing, nothing but bills and flyers. Still I wait, and I’m always disappointed. There is no one to write to me. The last letter from down there showed up fifteen years ago. I can order books by mail, but it’s not the same as a letter. I have no idea what kind of letter would satisfy me, what kind I could expect. Strange news, revelations, someone who remembers me, or maybe another invitation of the kind I refuse as a matter of habit. Anything, as long as it’s personal. But nothing comes. I watch for him, embarrassed to be waiting. Once he’s come and gone, I can return to my thoughts. As consolation, I warm up the coffee and light a cigarette.

And stare out the window. The blank grey world of winter is held fast, suspended in a cotton-wool mist. It reminds me of the handful of childhood snapshots I’ve saved; they, too, are frozen in time, their edges frayed. No matter how hard I stare at the faded sepia images, my past remains closed off. My attempts at bringing it back to life produce only a pale reflection. Even the photograph of who I was remains foreign and artificial. Slowly, I’ve developed a kind of tenderness towards this little boy, gained a bit of sympathy for him. But nothing more. The pictures are the only evidence that a childhood ever existed somewhere in time, far from the icy vision that reaches me through the frosted window.

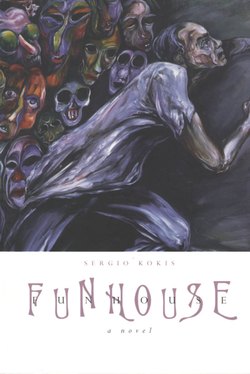

In this exile’s existence that is mine, only a handful of compelling images have kept the colour and movement they had when they were engraved in my mind like wounds. No stories accompany them, the living past has faded, but strangely the images that obsess me have kept all their wild exuberance. These ghosts, this legion of characters pulsating with light, continue to pursue me, demanding reparation. Some of them shriek, their bodies contorted like paralytics, others squat motionless, clutching themselves in silent, pathetic suffering. Others are little more than faces, disguises. One day it may be Carnival, the next day Lent. Many are corpses: inert bodies, nameless dead in a colourless setting. Frigid, grey, brushed with hues of cobalt, or chrome-green edging toward violet. There are children with distended bellies and stick-like bodies. Children who laugh and run like real children, children covered with pustules, teeth rotting, globs of snot dripping from their noses. One is sucking a lump of brown sugar, another is reaching towards a little girl who feigns modesty despite the dress that rides up her thighs. Desiccated old women stink of tobacco, sweat and coffee. No sooner do I close my eyes than these, and thousands of other images, begin to whirl before me like tireless dancers in an infernal fandango. Strange how the surface of things can be so commonplace compared to what we see through closed eyes.

I lower the blinds to keep from being disturbed. Mine is clandestine work. Beneath the raw glare of the spotlights, I surrender to my secret vice. That’s how I’ve tamed the images that are so powerfully resistant to the artifices of reason: I paint them. I turn them into chimeras. The underlying rot loses some of its energy as it burns into pale light. Once these images held me captive; I was their creature. They would appear whenever they wanted to, without warning, and there was nothing I could do about it. The fine dust of time that obscures the details of memory wasn’t enough to relegate them to the past. That’s true no longer. As they turned into objects, my images grew disciplined. True, I’m still a little scattered. Behind the outward calm, my inner world is in constant movement. Possessed, for the images refuse to fall silent, they won’t slip behind me like a guilty conscience haunting the present, or a depression in reverse.

In my studio design, I sit in a dark corner at my table and receive the full reflection of my paintings. Everything is illuminated in my eyes. Cigarette smoke helps give contour to the frozen surfaces, the way heat rising from the earth seemed to moisten the shapes in the sunlight back home. The paintings leaning against the wall are like the masks I wear to capture fleeting visions that are revealed to me even as they vanish. Of course this light, an entirely reñected light, is not real life. It’s a kind of theatre, a pure abstraction. But the images of ghosts can step onto that stage, and cease to haunt me. I’ve found no other way.

Making peace with the blinding light that pursued me came at the expense of everything else. But the price wasn’t too high because, for as long as I can remember, I have been a man of memory. A prisoner of the cinemas of the imagination with no desire to escape. I carry the walls within me. Though I attend to the present, I always compare it with images of the past, to such a powerful degree that new things quickly lose their interest. Once I wanted to escape from solitude. Now I’m happy to go unnoticed, I turn down invitations, play the chameleon and take the intensity of my fellow beings with a grain of salt. Solitude behind a puppet’s congeniality is the only bearable position for someone like me. Meanwhile, the images I have put on the painted surface become less foreign to me, almost mine, ultimately benign, for I am serving them.

When I lower the shades of my studio, it’s like closing my eyes and slipping into a more brilliant reality. I disappear into a world where greyness has disappeared, where the colour of my canvases sharpens and warms the surroundings.

What stunning confusion surrounds me! Throngs of real images crowd around me everywhere like a giant carnival. Against the wall stacked atop one another, rolled or stretched, piled up, stored in boxes, filed in folders, drawn, engraved, painted, pencil-sketched, washed, dried or still gleaming with fresh oil, on panels of wood or zinc, on canvas or paper or huge sheets of particle board. I have moved from the confused scribbling of my childhood into this florid jungle inhabited by multitudes of human reflection. My basement has become a pyramid’s crypt, holding within it a funeral procession of images transformed into simple, harmless, colourful mummies.

As I create in solitude, other apparitions arise through mutual excitement. I have become a maker of images, and by channelling this flood of stagnant waters, I have transformed it into a virtual torrent. What does that matter, as long as I work, without thinking, my mind empty, letting one thing follow the other, automatically.

Sometimes I tap the brakes lightly to avoid losing control. Creation happens by itself. I surrender to the movement just as, long ago, I drifted downstream, lying on the bottom of a rowboat, touching the oars only to steer clear of the riverbank or the rocky shoals.