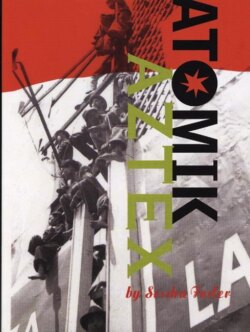

Читать книгу Atomik Aztex - Sesshu Foster - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеIN the early morning hours, the week before the rear end in my van went out, I was driving home after pulling two straight shifts, the streetlamps going north on Soto splintering on my windshield as if the glass itself was shattered in a massive web and then falling out of my peripheral vision like burnt-out flares. I was totally exhausted after a week of pulling back-to-back shifts, not just the hauling of the hog carcasses for 16 hours straight, but the filth, and most of all the noise. I worried about my reaction time, I didn’t want to hit them when the two girls walking thru the warehouse district turned around in my headlights, I didn’t know if I was seeing real people or shadow images projected from the back of my mind or from headlights coming in the opposite direction; this in an industrial area where you never see pedestrians day or nite. For good reason. The women stuck out their thumbs, and the van bounced across the railroad tracks as I swerved to the side of the road, a couple of semis blowing by. I leaned across the passenger seat to unlock the door & push it open. I turned down the radio. “Hey!” the shorter, lighter one said, “Where you headed? Give us a lift?” “I’m headed to the 10. I can give you a lift to town.” She hesitated, craning her neck to scan the darkness in the back of my empty van. “All right!” she barked; I could see she was at least in her late forties, thin brown hair cut short, though she looked like she might be fifty or more. Her face was lined and weathered around the bright blue eyes as if she’d spent a lot of time outdoors. Like her companion, a dark-haired dark-eyed twenty-year-old (whom she told, “Climb in the back”), the older one was dressed in Levi’s and a t-shirt. They didn’t have anything in their hands that I could see. “Where you going?” I turned to ask the younger one; she didn’t answer, casting me a suspicious, fearful glance. Maybe the younger one didn’t speak English. “Hollywood!” the older woman answered, “We’re going to party up in Hollywood!” I nodded, pulling out onto the avenue, heading north. I hadn’t gone a block, stopping at the next light, when the older one, raspy in her harsh, smoked-out voice said, “You like to party? You wanna party with us?” I looked back at the younger one in the rearview mirror, her dark glance bouncing off mine with a nearly audible crack like a billiard ball, as I said, “I don’t think so. Not tonight. Just pulled a double shift at work, you know, kinda tired.” Not to mention that I smelled like shit—that mix of smoke, blood, pig fear, pig excrement and death that coated your skin after a single shift inside the plant, not to mention two shifts back to back. I wouldn’t even want to piss or drink a glass of water until I showered. Then, I knew, I wouldn’t feel like moving at all. The older one studied the side of my face as I drove. My hair was plastered against my temples by grime and sweat. “Come on,” she urged, trying to put some purr in her gravelly throat, “People tell me I give the best head they ever had in their life. Nobody can do it like I can. Why don’t you pull in somewhere up here where it’s quiet and we’ll get down?” I wasn’t going to tell her she looked so turkey-necked mean and tough that the thought flashed thru my mind that maybe she was a cop, the kind of cop who would shoot you in the neck & plant a cheap pistol on your ass if you told her she wuz too ugly. To make conversation, to go the distance, I made small talk, stuff like, “How much you want?” “Twenty.” When I cast the girl in back a glance in the mirror, she was studying the passing street like none of this had anything to do with her. “Ten then,” the older woman said. “Too late in the month,” I had to say, “I’m broke. Don’t get paid till next week.” “Come on,” she said, “You sure? I’m really good.” “That’s okay, thanks,” I said, “but can I give you my phone number? Maybe if you’re around here again, we could make a date. I work nearby at the Farmer John plant.” “I could tell that. Believe me I can tell,” she said. I wrote out Max’s name and phone number on a piece of paper and passed it to her. She looked at it like it was no use to her. “I’m a fore man at the plant; you call that number any night and ask for Max. I got a private office upstairs, and if you come to the main gate, just ask the guard where Max’s office is. What’s your name?” She hesitated a beat, “Vicky.” “All right Vicky, I’ll be waiting for your call, sometime soon, okay?” “Not tonight?” “Not tonight, sorry. But come by the plant another nite, Vicky,” and I met the gaze of the girl in back in the rearview mirror, “Bring your friend, too.”

1 A.M., or whatever it was, I emerged from the tunnel near Union Station and turned into the Terminal Annex parking lot, the post office open all night, let out the two prostitutes I’d driven out of the City of Vernon. Worried they might get in trouble, I told them they could get a ride in front of the train station and pointed out the taxi stand on Alameda, they nodded and walked up to the corner. I turned my van in the blackness under the big dark eucalyptus trees and went right at the light. The women had crossed Alameda to Sunset, so at least one of them knew the town. A few cars followed me thru the intersection and in the rearview mirror I saw the older one, the smaller, stick her thumb out. I drove up thru Chinatown to my apartment building at the foot of Chavez Ravine. The streets of Chinatown were of course empty, black & reflective in the wet, everything smelling damp and fresh thru my open window. It’s a great thing, that fresh air after you pull two shifts back to back in the plant. I could smell the scorched blood on my skin & clothing, but I kept the window open as I drove, driving into the fresh chilly edge of the wind. Chung Mee’s was closed as I went up Alpine Street (they told me the card games in the back went on till morning, I don’t know, I can’t play Chinese poker), but the lights were still on. In front of the open door, a guy in a white apron swept the sidewalk as I went by and I caught a steaming whiff of rice porridge that roused a sharp hunger. I dwelled on that hunger as I drove up the hill. I expected I’d find old leftovers in the refrigerator, something I would wolf down cold or heat in a frying pan. Failing that, I always had one last can of chile beans in the cupboard. I parked the van with the other vehicles behind the main building and climbed the rickety back stairs to my apartment over two garages where the owner kept old cars and construction supplies. I paused midway up the stairs, not becuz the stairs shook against the clapboard side of the building like they were in danger of collapse, that was nothing new, but because something wuz wrong. My sense of familiarity felt wrong in some way. These old steps, I’d run up them a million times, so what? I scanned the silent parking area, but nothing moved, not even a mouse. Or a cat. No lights in any of the windows, no one moved in the shadows. Had I heard a noise? What was the source of the sudden difference I was feeling? I turned & ascended the stairs, listening. I heard nothing in particular. Inserting my key in the door I stepped into the kitchen, and it came to me. This was my old place, the place I’d lived in some time ago. I don’t know how many years previous, but it felt like a long time. How was it I had returned? I closed the door behind me. It rattled in the familiar old way as it closed, as if trying to irritate the silence of the dark apartment. My hand hovered over the light switch, hesitating. This feeling of deja vu, maybe it was just a feeling. Just a symptom of redoubled fatigue. Just a figment in the mind, like gaping holes you can see in the road after driving all night. That must be it. This deja vu was just an illusory feeling that came from working too hard. I turned on the light and it flickered, as always, before it fully came on. On the kitchen table in the pale glare, a plate of cold chicken and potato salad, silverware on a napkin. An empty glass, a pitcher of iced tea. But how long had it been since I’d come home to dinner waiting for me? How long had it been since I’d come home to someone else sleeping in my bed? I walked quietly across the ugly linoleum into the hallway and leaned into the nearest bedroom. The children breathed softly in their beds. I smelled her presence as I walked into our bedroom. This was the way the apartment had smelled when the wife was living in it. It made the air alive, her inhabitation of it, and I realized she was there, nestled warmly under the covers. “Did you see your dinner?” she murmured sleepily. “Yes,” I said, a hoarse whisper I barely heard. “Take your shower then and come to bed,” she said. “I will,” I said. What do you know, I’d gotten home again somehow.

Sometimes you can wake up from such a deep sleep, exhaustion so deeply embedded in your bones that it’s hard to move, and there’s a momentary confusion. As usual, the late morning or mid-afternoon sunshine filled the curtains with idle heat. The vague memory of my own snores buzzed around in the stillness like forgotten flies. My throat was dry, almost sore. My legs ached for no apparent reason.

My children’s young faces, school photographs in school uniforms, smiled with sweet blankness from the frames my wife had placed atop the dresser. The smiles swam through my yawning, and as I groaned, dropped fast through a ragged sigh. I had swung upright, meanwhile, my feet on the carpet, as my knee made snap crackle pops like Rice Crispies, as it did every morning. The shiny crescent scar itching like it does first thing, as I scratch, and it is apparently 1:22 P.M. by the clock. Better not to consider what it is I might look like, stumbling from the bedroom, rubbing my head, splash water on face.

Reassurance of a ceramic cup, cold coffee in hand as I emerged shirtless from the sliding glass door. I wasn’t sure how to deal with the overwhelming glare of sunshine on this new day; there’s the impulse to go back to bed, but I kept moving forward. Probably there existed some shade, some protection. I paused to sip at the cool caffeination, squinting to get my bearings.

After rubbing my eyes, I got a view of the backyard, the density of bright lawn, avocado and eucalyptus trees hanging semi-bedraggled from the slope above the yard, brush as thick as chaparral on the hill above the retaining wall, chain link fence up top. The flower beds my wife had planted along the foot of the wall and in every corner of the yard projected electric hot pinks, affirmative yellows and red-oranges into the daylight. Some colors so hot I expect they would reflect warmth onto your skin if you held out your hand to them. In spite of their brilliance, she was on her hands and knees at the edge of the lawn, and one of the beds had been literally turned over, laid to waste, dark soil exposed in a new furrow. Her thick dark hair was coiled in a bun at the back of her head that shook gently as she chopped at some roots.

I stifled a yawn, trying to speak, “What are you doing, Xiuh?”

Xiuh drained her plastic cup and placed it on the grass without speak ing. This time of day, she favored Chilean wines, as she worked her way through Trader Joe’s imported specials. Xiuh liked South Africans better than the Australian stuff, but Chilean, she said, was about as good as Californian. She went back to work with the spade, and I thought she didn’t hear me.

“What’s the matter?” I asked. “The flowers look good.”

“Yeah, like you know something about it,” Xiuh said.

“Just seems like a waste to rip them out when they’re still looking good,” I shrugged.

“Look,” she hissed, too furious even to look in my direction, “I don’t bother you when you’re having a good time.”

“All right!” I said jovially. “Would you like me to get you a refill on whatever it is you’re drinking?”

She didn’t answer, but turned to pull out another plant, leveraging the roots with the spade in her left hand and when they snapped free, she shook off the dirt. She tossed the plant onto the pile and shifted slightly to her left. For some reason her empty plastic cup called to mind a time years ago, an empty plastic cup she used to leave on a formica kitchen table when the kids were still living with us, long ago, when we all lived in a rickety apartment with one of those ice boxes always so frosted over that nothing could be put into it or taken out of it, in Chavez Ravine, above Chinatown. Once upon a time we lived in a rickety clapboard apartment the wind rattled on stormy nights in Chavez Ravine, in sight of the bridge for the 110 freeway, and in those days when the kids were small she rode herd on everyone with the tenacity of a sheep dog, writing unwritten lists of numerous things we had to do (I gave up trying to figure out when she’d be done), insisting we attend lectures, meetings and forums in a communist bookstore downtown, at the same time she was attending PTA and school council meetings at the kid’s school, on weekends making picnic lunches so we could all take the bus to the beach or hike in Elysian and Griffith Parks, then when she made friends with a fisherman in the neighborhood, besides getting a yellowtail or barracuda out of the deal once every couple weeks that was the freshest fish we ever ate since we cleaned and cooked it ourselves that same evening, we used to go out sometimes on his boat or borrow his poles and fish from the pier. We had to work the plot in the community garden, or failing to gain access becuz of a bureaucratic rule, make windowbox planters. Why read that trash; the library card was useful for checking out how-to books. She had friends who were musicians we’d go hear play at auditoriums or open air concerts sometimes at benefits for campaigns or political causes, and sometimes she sang as she worked around the house. Funny how Xiuh always used to be the one pushing us out the door to do new things and see what these people were up to and now—nothing; no more interest in any of it. Her empty cup reminded me that I hadn’t heard her sing like that in fifteen years. It took us decades and many thousands of miles to get here, and apparently she’s over it. Nowadays if you mentioned there was Chris Hani speaking about South Africa or Dolores Huerta talking unions on the avenue, or a community meeting in the church basement, she’d shrug and give you a flat stare. If you pressed her on it, she’d become annoyed. Things that had tickled her in the past, now made her upset and angry. If you suggested an outing to the pier, she’d sneer (“Ride the bus all day to come back tired, sunburned and sandy? Hang out with those wacky whities at the dirty beach? The water’s polluted!”), or mention a hike at Elysian Park, she’d complain, what was wrong with me—wasn’t I tired enough from work already? I certainly was. Where had the intervening years gone?

Recently I seemed to have dreamed a dream about it.

In vast lots under corrugated tin roofing behind the plant it smells like the county fairgrounds at 4 A.M., semi after semi entering row after row of sheds, ramps deployed with a clatter as thousands of hogs are unloaded into the gated pens, grunting, squealing & squawking like sports fans, huffing & puffing as they descend heavily into the concrete pens covered in straw as I sat on the subway next to a sweat begrimed warrior reading the Toltek Times with the headline, STALINGRAD SURROUNDED, ASTROLOGERS FOREKAST DOOM FOR GERMAN 6TH ARMY. My kid brother was a military advisor to Makno’s anarkosyndikalist forces, but I didn’t believe anything I read in our papers about the war. The only thing they were good for was reading between the lines, massaging the temples and listening half-heartedly to fleeting wisps of your flagging aspirations on the patio while the radio played Duke Ellington, Satchmo, Mayan covers of Miskito kalypso and Central Amerikan blues. That’s what I planned to do before my afternoon siesta. I knew my wife had other things planned for me, but if my maneuvers served, I’d soon voyage down kanals of dreams in the birchbark canoe of drowse. I got off at my stop and went through the turnstile, hardening my piglike eyes in my mask as a Warrior of Caste, which kept the riffraff half-Spanish Mexika, Zapotek and Mayan street urchins at a distance, my martial stride emboldened by a purpose that I no longer bothered to feel or even seriously consider but wore like a Clan Elder’s feathered cape at some banquet in my honor, making my way through the disembarking throng without a glance either right or left. I stopped at a kart at the korner of my block and imbibed a pipette of coka krystal and two jolts of expresso, knocking back one after the other without regard to the possibility of kaffeine addiktion, and then a tobacco chaw to cover my breath as I took the back route into my house: north through the service alley behind the kompounds, in through a backdoor to the sunken garden where my sleek ocelots and mangy jaguars prowled, sleek as a shadow myself moving through the stinking, humid, lush jungle foliage, past my authentik replicas of gigantik Olmek heads whose gaze is fixed on the doorway to other levels of existence (admittedly, used largely for recreational trips to get away from the frenetic hustle of overcrowded Teknotitlán), to squat momentarily above the sunken cages where I’m required to tend the usual lot of ritual kaptives. As usual, they locked their eyes on me as I appeared before them in the carefully tended gloom, thinking (this I knew from interview and experience) that I was at once Angel of Death, Olmek were-Jaguar, barbarian lord of the underworld in the service of Satan, vicious slayer of thousands or—for all they knew—millions of their men, women and children, Executioner (“verdugo”) sitting in judgment on their entire doomed civilization, etc. The Europian savages simply had no koncept of how much thought we put into their kareful selektion and processing as centerpieces for State Ceremonials. My own cages, for example, were equipped with the most up-to-date kontemporary stylings, with every modern convenience including running water (overhead sprinklers to wash down both cage interior and prisoners at the same time), electricity (for both lighting and nonlethal elektroshock training), scientifikally determined square footage per prisoner designed for maximum efficiency (derived from ancient texts of the Kalifornia Youth Authority showing how to keep juvenile individuals in personal cages in classrooms) in order to preserve the sakred human characteristics which were of immanent and ultimate importance in the teknospiritual festivities which preserved the benefits of Aztek civilization for the Western World. I knelt by each cage, skanned the upkast faces perfunktorily, making an approximate headcount to make sure the pathetic kreatures hadn’t begun consuming each other or done anything contrary to the Municipal Code for the Preservation of Kaptives. I never liked to get tickets for speeding or slavery. The eyes of the slaves were uniformly light-colored for the most part, gray when the light caught their upturned faces, the vision in their eyes glazed with something like illness, which I took for ignorance in its purest form. Dust swirled in the darkness of their gaze and alighted on their unkept, shaggy heads. Among the adult cages, I thought I crossed gazes with some who evidenced a piercing intelligent hatred, who seemed in their pitiful barbarian krudity to wish they could will me inside the cage with them in order to tangle with me in kombat of some untrained and hopelessly inelegant form. That was always the best sign. No weeping, breakdowns and tantrums among such cages, where the kaptives were adept at plotting futile resistance that played right into our need for passionate Hearts. Such kaptives were of course prime quality and would bring me the greatest return on my account with the Clan Elders, among whom I was known to supply red-blooded Hearts, mostly of Europian stock. You want to enkourage such thinking by treating them with as much supercilious kontempt as you can fake—you must keep your affektions a secret. I passed by the cages of the children without stopping because I didn’t want any noise in the garden to alert my faithful animals to my presence, as any sudden shift in the dreamy pattern of dappled foliage, sacred animalia, chirping jungle birds, invisible ghosts and other half-imagined presences in the garden might alert my wife to my arrival. I hoped to ascend to my hammock on the patio and fall asleep under my newspaper before she found me, knowing that she invariably left me alone when she came upon me napping. I had to give her that, but I was not above using that minimal generosity on her part for my own purposes. I should have avoided the children’s cages entirely however, because something in my passing set off a keening among them which I knew would alert Beppo, my old male jaguar. Even though I was able to get to the switch for electric kurrent and give the row where the children’s cages were situated a stiff debilitating zap which quieted them instantly (I paused for a moment to allow the kurrent to work its magic well into the bone, somebody’s teeth set a-chattering), I heard Beppo’s low cough. Perhaps my wife was otherwise occupied, was all I could hope. Feeble hope, I should give up such pitiful evasions; she and every other woman in my clan seem to be two steps ahead of any scheme I try and fob off on them. In fact, she lay kurled in my hammock herself, the leafy shade soft on her lithe chokolate skin, the big toe of one foot sexily thrust toward the skudding cloudcover of the day. In spite of my better judgment, I paused to take in the scene, and there it was, she had me; though she appeared to be sleeping, her head turned in my direction as if accidentally. A sekond sooner and I might have been able to fade back into the bushes, step behind the massive footing of a giant fig strung with lianas, but now I was stuck kontemplating whether she was asleep behind those sunglasses or not. Not, I thought. Sure enough, momentarily her upper lip kurled in a languorous inward half-smile. Was she pleased to see me, or pleased with herself? Both, perhaps. She cocked her head to one side, removing her shades with one hand and slipping a temple into her mouth, smiling at me as I came up out of the garden. I admitted defeat with every step, I was about to seek forgiveness for the plain bone-head prediktibility of my behavior. I had no right to be as dull, transparent and entranced as I was, in the presence of a woman of her character, and she knew it. She held her hand out to me.

Shuffling in the sticky black blood, shuffling in it, shuffling, singing your death song under your breath, klimbing the steps into the sun, it skours out your insides with light—she makes my heart race; floating out of the undergrowth like a butterfly; the sunshine radiates, splayed on her dusky skin —shuffling in black blood up the steps, each sticky step mucking, mumbling mumbo jumbo to keep the mind’s eye carefree, moving on automatik, sweating already, embracing whirling shadows inside an advancing doom—her mouth is painted black, Aztek-chilango style, she smiles; her teeth flash behind the parting black lips of the married woman—we’ve come out of the mountains of the underworld, underwater worlds of rain and misery in the submarine black light of no moon, new moon burning in water, endless roads of night with vultures inside vast emptiness of lost souls, drowning in flame, krucifixes in a death hand, wailing women who are happy for us—touching her skin is relief from something, I don’t know what, but it’s sudden and all-enveloping like exiting from a canoe after a long period of confinement, a long endless canal, a liberty palpable in the paired eloquence of her hands; it’s an awakening into a suddenly better place, one that had somehow been forgotten in all the hectic traveling of my big important days. Making love to my wife is always a beautiful thing. It’s like stepping out into summer vacation after a long year of Aztek High School, you don’t even want to know about that. But this thing with my wife, it’s always been that way. I don’t know why. It’s not the same with other wives, other women. It’s not like she and I have some perfekt wavelength, some perfekt rapport that makes it work right every time. I’m sure there are other women, probably I’ve koupled with enough of them myself, who are stronger funnier more imaginative krazier more delikate more this or that more scented with exotik fragrances more pronounced in some obvious way in sexual performance. It’s not that obvious with her. The enchantment of her lovemaking is as subtle as the chiaroscuro along her jawline a twilight border that I like when it tastes of her salt. One of the top women in our society because of her tenured position and power in the Akademy of Sakred Aztek Sciences, my wife brokers her own social power with graces, charms and sexual relish. Sex with Xiuhcaquitl always rolls like a ride through the rapids on the river of one’s own helter-skelter destiny. Sometimes she chugs sluggishly like a river tug pushing a loaded barge (tacking back and forth slightly) up a muddy roiling jungle tributary; sometimes she’s desperate, mean and short about it as a cat; sometimes she starts at it slow and she’s a long, long time like she has to voyage a distance within herself and fetch something she’d forgotten some time ago. But her body’s always a blessing when I come to it, a pissing warm tropikal rain, a waterfall into blue pools, flights of egrets across the central kauseway of the kapital on a good day; the benediction of her perspiration on my belly and thighs or calves is sweeter, a sweetness more substantial than the souls flying through the treetops on dark windy nights. She rides her own sensations into a kalm inlet, shifts over me or turns and lifts me above her, moving to increase the Effekt. She and I have been married many years and the sex has always been good. No matter how badly everything else goes in any other part of our lives, including kommunication with our ghosts or treatment of each other, when we make love it’s good as it ever was. Even when we’re not getting along, like nowadays. We’ve been in a slump for a year or so, not as bad as the time when she moved out and was living with some Tlaxklalan mercenary geek, martial arts nerd, skrawny methamphetamine zombie, but these days things weren’t going very well for us, either. So what? So much for the ups and downs of life; I dispensed with these cares making love to Xiuhcaquitl. She rubbed herself against me; she perfumed herself with my fluids at the four points of the human kompass. Done, I left a glistening slime trail across her glowing skin like a meadow snail on a misty morning; Xiuh reklined, tracing little circles on my chest with her fingertips. Then she got down to Business. “Let me guess. The Clan Elder, that old monkey’s flaming red asshole, he says it’s a sure bet, this Operation. It’s all there is for it. Wait a minute, wait a second, Zenzón, let me finish—that’s right, he said it’s just a matter of the best Aztek medicine can provide, teknospirituality at its finest and most precise, that grinning toothless fuck, and you hemmed and hawed and finally just shrugged and said, yeah, sure, why not? Eh? What? That’s not exactly what you said?” She allowed for my reply. Then she continued: “So that’s not exactly what you said. But that’s sort of the way it worked out, wasn’t it?” I didn’t answer. I imagine I was staring at the kolor orange through my closed eyelids. “I knew it. I fucking knew it. I knew I should have sent your Double in your place. That old fuck would never have known the difference. I could have assumed total control of the Double’s functions and negotiated the entire meeting. Like I did with the Tlatekatl Kouncil, you would have been in the shit with them, you would have been fussing with them, you would have messed up, you would have said the wrong thing, you would have told them things they didn’t want to hear, they don’t want your rationales, they would have demoted you, kashiered you, erased your pension, taken away your various insignia, stripped your name from the official accounts of the Europian Kampaigns, blotted your face out of the official stelae raised in the towns of stone monuments, assigned you to be piss-pot monitor at some third-rate Tlalok temple in Guatemala, Huitzilipochtli, I skatter jade before you, but they heard my words, my words coming out of your mouth, heard and were made aware of your kontinuing usefulness to the Kause of Our Socialist Imperium and furthermore to their own ascending prestige as Honored Faces Among the People. I saved your butt on that, you still have the sidelines of specialized slave-trade, you have your Unit intact, supporting you, you have a prosperous practice as Keeper of the House of Darkness, you have unkounted and unkountable blessings that you don’t bother to even stop and imagine, and now you’re gonna let some third-rate Clan Elder from your old barrio talk you into this new-fangled Operation just cuz success is going to your head?” “I’m not sure about this success, so-called success,” I sighed, “I’m having second thoughts, third thoughts, strange ideas, funny visions, sideways apocalypses, nervous glitches, chicharrones, juxtapositions, pickled pigs’ feet, moments of spasmodic nerdiness, cloistered hogwilditude, fornicated bowdlerizisms transposed on flights of fancy. I can’t stand myself.” “Just don’t forget who you are and where you came from,” Xiuh kommanded softly, her hand coming to rest gently on my forearm, “Remember that. And think of me, why don’t you? Konsider what this means to me, for once. Huitzilipochtli! Think of what this kould mean for your children’s future.” “Actually, that’s one of the things I have some doubts about,” I began to say. “Oh!” she rushed a finger to her lips, her gaze rising into a middle distance, “I forgot to mention it, but you got an important phone call from Rixtl—he said someone’s trying to kill you and all your men. Yep, he was pretty definite about that. He said he thought maybe it was someone close to you, yet somebody on a whole different world. He said Moquihuix was killed today and that it’s only a matter of time before they kill you all unless you do something about it. So do something about it, won’t you? Please.” “Yeah, yeah,” I sighed again. “Same old shit. More Party business, I’m sure. I was hoping they were just out for me. You better assign more guards over the kidz. Watch it when you take Ahui to soccer.” “Well, you take care of it!” Xiuh urged gently, “It’s your job!” “I will,” I said. I thought the better of telling her about the rest of the day’s events. She pulled her arm free from my side, chicken-winged and bent at a kramped angle in the hammock. One of our old slaves who’d amazingly escaped all Xiuh’s fitful purges of the household staff had grown bored with watching us now that we lay quiet, and we kould hear him scraping the short-handled hoe in the garden. Our fluids had dried and stiffened like flecks of mica on our skin.

It wasn’t easy for me to get a good job like this in the meat industry. I wasn’t born working in a slaughterhouse. I crossed deserts to get here. I traversed the mountains of the Rumorosa & the Coast Range, skirting secret borders of forgotten history & identity. I sacrificed the Past, relationships & dreams of community. I tore open blisters & stubbed my toe on rocks. Empires lay in ruins along the way. I survived long odds, bad luck & bad trips as one of a select few. I negotiated with coyotes, rubbed elbows with travelers from everywhere, hung out under the watchful eye of the Migra. Lots of people—maybe most—don’t make it this far. When the maroon Buick Riviera rolled over 4 times in the desert outside of Riverside, who do you think climbed out of the trunk & puked on a rock? When 19 other vatos were asphyxiated in a boxcar locked in the Arizona sun, who you think was the last left alive sucking air out of a tiny rust-hole? Who you think tried hardest to live & go on? Who you think kept walking across the desert with water in plastic jugs on both ends of a stick when the rest of them gave up, wandered off to die bloated & black under a bush? Those ain’t my bones unknown out there, not my teeth scattered out there like a broken necklace. Mice ain’t making a nest in my jacket elbow. Sow bugs ain’t sleeping under what’s left of my shoes. Blackbirds ain’t playing tug of war with tufts of my hair. Rattlesnakes ain’t sleeping in my last resting place. A cottontail ain’t hightailing it from a piece of paper with my name on it blowing across a gravel wash. A creosote bush isn’t wearing one of my socks. The wind isn’t whispering my last words. I stayed alert at all times to every possibility in any given moment. I had to keep my mind alive to the multiple chances hidden inside every second. I had to feel the potentiality of the living moment, where every next step could lead to Death or to Life. There are secret worlds hidden in the air, secret possibilities that can keep you alive in the worst of situations. You got to find them or you may not make it. When the odds are all against you, you got to consider that there might be one possible thing you could do. Or one misstep to avoid. Your life depends on it. That’s why I think like this. It’s gotten me this far. I been waylaid, ripped off, lost & turned around, and still I made my way. I offer you suggestions on how to survive. You go thru all this, you too can get yourself a job in some industrial section like the City of Vernon slicing the heads off pigs with the circular saw descending from the ceiling, its yellow electrical cord recoiling overhead, hogs’ heads rolling across the floor (with a helpful kick every now & then) as you reconsider behind dripping plastik safety goggles the fakt your wife really left you in spirit a long time before she departed in the flesh (you can see that now, as the saw bites thru the neck of the next hog, bits of skin shredding as you press the ripping business end all the way thru the spine), I concede I still owe my ex-mother-in-law two grand for a front end repair that didn’t work, my kids who don’t talk to me anymore are now gangbangers or evangelical christians—now that they got it made in Amerika they disdain me, my values, everything I sacrificed & worked for. This thought alone might’ve killed me if I let it. Sometimes I did want to die. “Better watch yourself,” I told myself sometimes when I caught a glimpse of myself, passing blurry by the little windows inset into the steel doors, I muttered to myself, “Sometimes your worst enemy is your self!” You heard that the suicide rate is 100% higher than the murder rate? That guy in the mirror, he was giving me some nasty looks.

Sometimes when 3Turkey’s Apache pickup left the curb, I glanced back over my shoulder to see a little house nicely decorated with flowers, burning brightly.