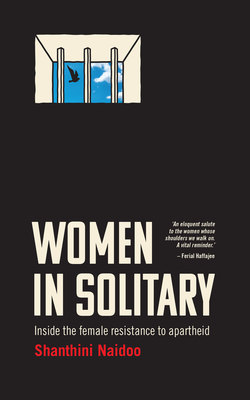

Читать книгу Women in Solitary - Shanthini Naidoo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

Оглавление6 April 2018 – Pretoria Central Prison

It is 4 am and dark, apart from a few dim light bulbs dotted around pathways. April’s autumn wind chills Gauteng, but the shivers that come and go this morning are not just from the crisp air. We are at the old gallows of Pretoria Central Prison. Cold steel, swaying nooses and an eerie breeze keeps everyone quiet. It is as if the memories, the spirits, of all the lives that were snuffed out here still linger.

The death of Winnie Mandela just four days before is on all of our minds and she is part of the reason why photographer Alon Skuy and I are here. We are in search of a narrative about her incarceration in a cell in this building in the 1960s and 70s to include in the Sunday Times’ coverage of her death and memorials.

But it is the anniversary of another death that we are commemorating and remembering today, that of Solomon Mahlangu, the MK freedom fighter who was hanged here on 6 April 1979. It is a sombre but low-key annual family ritual – the re-enactment of his final walk, 39 steps, to the gallows. The last words he uttered were: ‘My blood will nourish the tree that will bear the fruits of freedom. Tell my people that I love them. They must continue the fight.’

The gallows were equipped to hang seven people at once, but historians record that the 22-year-old was alone the morning he was hanged, at 6 am, as the dawn sun was lightening the sky.

The young recruit, fresh out of the ANC’s military training camps in Angola and Swaziland, had been tasked with crossing the border into South Africa with grenades and pamphlets. The Mamelodi student, new to politics and impassioned by the ’76 riots, was so green that he and a friend were easily detected for ‘acting suspiciously’ not long after arriving in Johannesburg. A gun battle with police ensued, in which a bystander was shot, though not clearly, by Mahlangu. It earned him the death sentence. This young life, lost tragically to the struggle against apartheid, is just one of so many atrocities of the era.

As he was led to his execution, Mahlangu would have been walked past the women’s cell block, which, ten years before, had been the home of Winnie Mandela and six other extraordinary women for close to two years.

After the ceremony, the prison authorities had promised to allow us time to locate the women’s cells and so avoid the red tape of seeking permission to access the high-security space on another day.

Now named Kgosi Mampuru II Correctional Centre, the historic and still functioning prison at the corner of Wimbledon and Klawer streets in Salvokop is made up of a number of imposing, flat and khaki-coloured buildings on the outskirts of Pretoria’s central business district. Here, political prisoners were kept among murderers and thieves. It was large enough for prisoners to disappear, particularly in the maze of solitary cells reserved for political detainees.

As the light starts to warm the day after the Mahlangu ceremony, we arrive at the red brick walls surrounded by green lawns and roses near the warders’ tennis court and sparkling swimming pool, a stark contrast to the vicious, dark days the precinct had seen during the apartheid years.

We walk along the cobblestones in search of Winnie’s cell – looking for the grey, blood-splattered walls she’d described in her secret diary – but if we expected to find it as she described it, we are disappointed. We come instead to a stone wall. All that remains of the original building, which dates from 1906, is a singular brownstone wall and a turret, preserved as a heritage structure. We are told that the building had been completely renovated and restyled several times since 1969.

One of the prison’s directors, Rudie Koekemoer, tells us it now houses day-parole and medium-security male prisoners. It has bigger windows, linoleum floors, a TV lounge and cells with cupboards in them, and toilets. ‘We tried to find the warders who might have been here when she was here, but many have died or retired,’ Koekemoer says. Like much of apartheid-era documentation, records would have been destroyed and officers of the time went silently into retirement or their graves.

The Department of Correctional Services has few details of the women’s time in solitary, because they were detainees, not inmates. They had not been convicted of a crime; they were not prisoners who had been charged and were awaiting trial, even though they were detained for that lengthy period. Many would not have received prison numbers.

‘From what she described from her window, her cell would have been on the east side, but the entire building (apart from the heritage wall) was renovated,’ Koekemoer points out. ‘There is no solitary confinement anymore.’

From the winter of 1969 through to the spring of 1970, in conditions so inhospitable that Winnie became gravely ill, she and the six other women who were held here, each in her tiny cement-floored cell, were removed only for sessions of interrogation and torture. Despite their solitary confinement, they stood together in spirit. Everything else around them was aimed at their demise, in physical form or otherwise. An excerpt from Winnie’s prison memoirs reads:

‘I am next to the assault chamber. As long as I live I shall never forget the nightmares I have suffered as a result of the daily prisoners’ piercing screams as the brutal corporal punishment is inflicted on them. As the cane lashes at them, sometimes a hose pipe, you feel it tearing at your own flesh mercilessly. It’s hard to imagine women inflicting so much punishment. I have shed tears … unconsciously and often forget even to wipe them off.

‘These hysterical screams pierce through my heart and injure my dignity so much. The hero of these assaults is barely 23-years-old, very often the screaming voice appealing for mercy is that of a mother twice her age but of course she is white, a matron (at) that, this qualifies her for everything. The prisoner is at her mercy, life and all. She even bangs their heads against my cell wall in her fury. As the blood spurts from the gaping wounds she hits harder.’1

It is an icy morning. We join the other members of the media who have gathered for refreshments. Everyone is chatting about Winnie, sharing the stories that have surfaced in the few days since her death and discussing the impending funeral arrangements.

I accept a hot mug of tea and warm my fingers around it.