Читать книгу Women in Solitary - Shanthini Naidoo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеTHE LEGACY OF TRAUMA

They say trauma lives in our DNA. It’s simple science, really. We are made up of many parts of microscopic bits. Some of these parts are physical, and others exist on a different level – subtle, intangible parts, in the form of memories, emotions and experiences.

When I think of the lived experiences of the women in this story, I realise that perhaps there is a scientific explanation for why I feel so deeply connected to them and their histories, even though we were born generations apart. Why I feel this in my gut, in a tightening at my throat, in overwhelming sadness.

When you consider a history like South Africa’s and witness the psychological mess we’re in today, why, I have to ask, do South Africans not honour and respect those who suffered for justice and freedom as it is set out for us in the constitution?

Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights.

If those that came before us are in our DNA, and it is mandated in our foundation document, these solemn words should at the very least be in our consciousness as we walk this sweet, flawed path of democracy together.

Democracy. This was not an ethereal concept, something that was yearned for to change our way of life, even though it might have felt like one. And yes, we may have a surface of democracy now, and slivers of light do shine through, but what about the deep, dark substrata below? When we ask, What went wrong? How did we get here? How could such a long road turn onto this path? perhaps one of the answers is that too few of us have the will to dig deeper, to penetrate those layers enough to shift our perspectives.

Fifty years prior to the writing of this book, a certain political trial – which was known as the Trial of 22 – impacted the country’s history not by an outcome, but by the absence of one. It steered the revolution against apartheid in a direction which subtly altered the road to democracy and the dismantling of the apartheid system of segregation. This trial, and others that came before and after it in the long, long struggle, may give us clues to why anger, hurt and unresolved trauma show up fresh and raw as a new wound five decades, a lifetime, later.

If we have to consider bookends to the struggle for freedom in South Africa, starting with Passive Resistance and ending with Armed Resistance, there are reams of stories in between. Along the way were the Women’s March of 1956, the 1960 State of Emergency, the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the Soweto uprising in 1976 …years and years until freedom arrived. What happened every day though? What filled the minutiae of the minutes and days that went on and on for those years?

The Trial of 22 or, as the record would read, The State versus Ndou and 21 others, fits halfway through the story, in 1969. What happened – or didn’t happen – in that courtroom in the Old Synagogue in Pretoria was quietly momentous. It was this trial that edged the movement on towards the ultimate goal, freedom, and yet there is little known or written about it.

It began on 14 October 1969. There were 22 accused, men and women, arraigned before the Supreme Court on 21 charges under the Suppression of Communism Act.

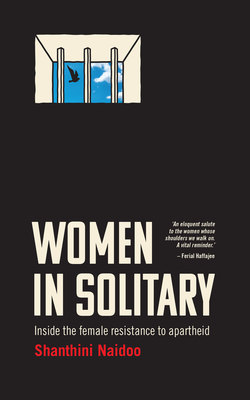

Among the 22 were seven women: Nomzamo Winnie Mandela, Martha Dhlamini, Thokozile Mngoma, Rita Ndzanga, Nondwe Mankahla, Joyce Sikhakhane and Shanthie Naidoo.

It was in April 2018, while reporting for the Sunday Times on Winnie Mandela’s death, that I first read about the trial. It turned out that four of the women, three of them in their 80s, were not only still alive but had attended Winnie’s funeral. Rita Ndzanga, a tiny woman with a waning, husky voice, and wearing a headscarf in ANC colours, delivered one of the many eulogies. The women were quoted in an article or two in the media, and then they went back home to their respective quiet lives.

I wanted to know who these women were, these friends and comrades of Winnie Mandela. What had brought them together at that moment in 1969 and what happened to them afterwards?

Martha Dhlamini and Thokozile Mngoma had since passed on, but I made contact with each of the four remaining women and asked if I could visit them. They promised time when the dust had settled. The lengthy funeral proceedings had taken their toll. They first needed to rest.

Fatigue hung over the funeral in another form. Working on a Sunday newspaper, as the coverage of Winnie Mandela’s passing unfolded, prickles of unease ran through me. Within a few minutes of her death on Monday, 2 April 2018 the electronic daily press was telling the basic story: that she had died at the age of 81; that she was a diabetic who had recently undergone several major surgeries; that she had been in poor health. Then, towards the latter part of the week, bits of hell bubbled up.

When international media picked up on the story, that ‘the wife of Nelson Mandela’ had died, my sense was perhaps that that particular context was needed for global audiences, but the prickles soon turned to full-on rage at how the media chose to remind the world who Winnie was: the fraud charges that were brought against her came up, as did her troubled past and a wayward youth. In fact everything from guerrilla warfare to extra-marital affairs, not forgetting murder, filled media platforms. One South African editorial alluded to Winnie being inebriated and with ‘not-so-good’ people at the time of Mandela’s release in 1990, and questioned why anyone would emulate her. The media offered many faces of Winnie Mandela, without revealing which face was actually hers, but it seemed that history was in danger of relegating her to a philandering drunk, turned-militant ex-wife.

But then, the social media heavens opened – you cannot die in peace in the era of social media – and in one of those rare moments it showed up as a force for good.

Journalist Kyle Findlay analysed some 700 000 tweets which showed that the early conversation around her death was ‘dominated by left-leaning communities who saw Winnie as a militant martyr who was not appreciated in her time and who was the victim of under-handed machinations, both by the apartheid government and by more moderate members of her own party, the African National Congress, the South African liberation movement.2

Many writers, and female writers in particular, stood up against the pejorative narrative and demanded that Winnie’s contribution be recognised.

Researcher Shireen Hassim described how women in the ANC were marginalised from its powerful decision-making structures. She questioned the stereotypes, particularly around Winnie. ‘Unlike male leaders, her personal life was constantly under the spotlight (no doubt aided by a zealous security machinery that kept her under constant surveillance), and she was judged harshly and unfairly for her private choices. Although she was a masterful player of the familial categories of wife and mother, she felt reduced by them too.’3

One of the things I wanted to ask of her detention mates and compatriots, the women with whom she had been jailed and tortured while taking up roles left by the imprisoned male leadership in the 1960s and beyond, was what they thought of how the media was portraying Winnie’s legacy. The answer was that they were incensed. Ma Rita included the publication I worked for among the ‘cruel media’ in her anger and refused to speak to me for months afterwards.

Winnie’s death reminds us that the female narrative of the struggle against apartheid, and in history, is vastly different to that of the male, and we are either not aware of it, or do not acknowledge the extent of it. What of the emotional impact on women like Winnie Mandela and the six other women who had been held with her at the same time prior to that 1969 trial? What led to Winnie’s ‘behaviour’ in subsequent decades? What must it have been like every day in the firing line while male leaders were absent?

Earlier in 2018, at the annual commemoration of the late Rivonia triallist Ahmed Kathrada’s death, the question of missing herstories was raised. In a video recorded shortly before his death in 2017, which was played at the tribute, Kathrada said that his life partner Barbara Hogan, a former minister, former detainee, had not told her story of incarceration and struggle, and he believed it was time. She avoided the question, but it was not the first time it had been raised. HIV advocacy group the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) some years before (2010) had published a brief ode to Hogan, saying: ‘When Barbara was appointed Minister of Health in 2008, most people did not know her. This tribute is written because she is a remarkable (almost anonymous) leader.’

At the 2020 inquest into the death of Dr Neil Aggett, an anti-apartheid activist who died on 5 February 1982 while in detention after being arrested by the South African security police, Hogan gave rare testimony about her own detention in a public space. ‘Can I just say that the reopening of the inquest (from 1982) is very painful for everyone sitting here, but it’s timely and I have just spoken of the terrors that I faced and many people faced worse,’ said Hogan. ‘Neil and everyone who died in detention under these terrible circumstances needs to have justice, needs to be heard and have justice done.’4

Hogan was detained in 1981. She was held in solitary for a year, then at trial convicted under the Suppression of Communism Act and sentenced to ten years in prison. ‘I was desperate,’ Hogan said of her period in detention. ‘I wanted to kill myself. I saw no way of my getting out of that situation because I knew of many people who died in detention. I had friends who had been tortured very badly at John Vorster Square. I knew what they (the apartheid security police) were capable of and I just saw myself being tortured to death for information I simply could not provide.’ She had tried to commit suicide by stealing the medication prescribed for her injuries, swallowing it all, and tying the cord from her dressing gown around her neck.

Hers is one of many stories of women like her, activists working for justice, journalists, wives of imprisoned cadres, and the female struggle leaders themselves. The women who participated in the movement are ageing now, and many have passed on. But there are a few who can share the stories of what happened in their minds and to their bodies when they were targeted by the apartheid government systematically to break down the machinery that ran on the convictions of those who believed so steadfastly in it that they would risk their lives and their families. The effects would last for years to come.

These women lived through harassment and abuse that was gender specific. Academic research by Professor Kalpana Hiralal at the University of KwaZulu-Natal reveals how female political detainees were treated particularly harshly. Gender sensitivity was considered a secondary weapon.

Strip searches conducted by male officers, threats and acts of sexual assault – inspection of every orifice by male officers alone in their cells; political prisoners told that their children would be murdered; denial of sanitary material – these were meant to batter women as fiercely as possible, attacking them at their womanhood. Hiralal described how ‘pregnant women were threatened with drinking poison by their captors, another had her breasts slammed in a drawer, repeatedly. The nature of women’s incarceration, interrogation, and the impact on their personal lives highlights not only the gendered aspects of imprisonment but also the heterogeneity of women’s experiences. Apartheid prisons imposed brutal and inhumane prison conditions that denigrated and humiliated women, thus becoming a site of humiliation.’5 But the worst, many women would say, was denial of visits from or news of their children.

Despite these conditions, women were far from compliant. ‘They negotiated their confined spaces through common sense, tenacity and a steadfast belief in their resistance and the justice of their struggle. The courage and sacrifices they made are important in giving greater visibility to both the tangible and intangible contributions women made in the liberation struggle in South Africa. The gendered prison narratives illustrate not only women’s contributions to the liberation struggle in their own right but also how the prison was another terrain of political struggle, resistance, confrontation, and negotiation by women,’6 Hiralal wrote.

There are suggestions that political prisoners have lived with untreated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Writing in a paper entitled ‘Truth and Memory’ for the Khulumani Support Group for people harmed by apartheid, Wendy Isaack wrote: ‘… the political compromises made in the South African transition failed to address violence against women and have left women vulnerable and victimised.’7

For me personally, visions of young women ripped from their lives, their families, mothers taken away by police while their young children watched, are haunting and I don’t believe I am alone in feeling deeply troubled by such images. If we pause to think about these women’s children, with long-absent fathers and routinely missing mothers, we may get an inkling of what wounds the current and subsequent generations of South Africans are still having to bear. If, as the science says, we carry them in our DNA, a deeper exploration will allow a deeper understanding. Few of the older generation have sought psychological help for the emotional trauma they suffered as a result of standing up for their political beliefs. It is my view that the outcomes continue to be reflected in South African society today.

In reading up on the Trial of 22 as much as I could in advance of meeting with the four remaining women who went through it, I soon realised that there is lean and scattered information about it. The bare facts were there, and the court record, which is a terse and unenlightening thing. I was banking on the women still having vivid memories of those harsh months 50 years later and being willing to tell me about them. I had interviewed them each telephonically for the news reports following Winnie’s death, but there was more of the story to tell.

I believed that if I was able to talk to these women, whose lives had been bound inextricably together in the late 1960s, the insights they might be able to offer of that time and their experiences at the hands of the notorious special branch would be a gift that I would not take lightly. I wanted to get to know them, to hear their stories, to better understand the context and the times.