Читать книгу Advanced English Riding - Sharon Biggs - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHoning the Seat and Position

All advanced riders want to achieve an independent position. Independence means that you’re in total control of your seat at all times, no matter what your horse does—even if she spooks or bucks. This seat allows you to move with any horse’s stride and with your legs lightly against your horse’s barrel, instead of gripping for balance. An independent seat also means you have the ability to maintain a steady contact with your reins, instead of using them as a way to stay on. Most of all, an independent position means you can time your aids correctly and use them effectively.

Checking Your Seat

To sit well, the rider has to be in a vertical line, over his own feet. Think about the best position to take if you are standing on the ground. You won’t stand with your upper body pitched forward or back; you’ll stand with your knees slightly bent, and your hips will be over your feet so your feet, your hips, and your shoulders are aligned vertically. In the saddle, you want the middle of your foot (in the stirrup) to be underneath your hip, with your knee bent to whatever degree your kind of riding dictates. Your shoulders should be in line with your hips and your feet. You also must be balanced laterally, side to side, and have equal weight in the stirrups, with your shoulders parallel to the horse’s shoulders and your hips parallel to the horse’s hips.

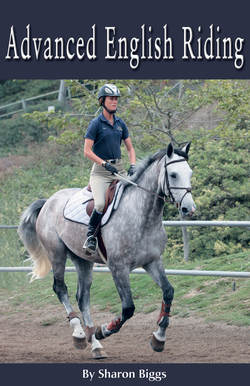

Here is an example of a good dressage position: shoulders, hips, and feet aligned, with shoulders parallel to the horse’s shoulders and hips parallel to the horse’s hips.

As you put your leg on the horse and ask for driving energy from the hind legs, the energy must be able to travel through your seat, which says to the horse, “I want you to stay in this length of stride, in this tempo, and in this gait.” Then your hand has to receive and direct that energy. Riders often want to know how much leg pressure they should use. Remember that a horse can feel a fly on his coat, so your aids don’t have to be huge to get a response; however, they have to mean something, or your horse will ignore you, and deservedly so. Therefore, whenever you use your legs, make sure that what you are asking for is clear and that you receive the correct response. Don’t wait five seconds or more. Repeat the request. Your horse may require a tap from the whip, paired with the leg pressure, until she understands that you mean what you say. Spurs are also a good aid, but make sure your leg position is rock solid before you use them. Spurs used incorrectly can make your horse dull to or, worse, frightened of your leg. The rule of thumb regarding leg pressure is to use just enough to squash a ripe tomato against your horse’s side. And always keep your legs against your horse, close enough to feel her coat against your boots. Hold your legs there at all times, even when posting, because bouncing legs can cause your horse to become dull to your aids.

Good Hands

Although the different styles of English riding require a variety of hand positions, the overall purpose of the hands remains the same: to communicate your intentions to the horse (for example, slow down, turn here, stop). Your hands are, in effect, a telephone and a way to relay your requests. These requests must be clear and easily understood. If not, your horse will be confused and frustrated and will give you the wrong response or ignore you altogether. Tense, unfeeling, or jostling hands create an uncomfortable pressure that even the kindest horse will come to resent. Riders with light, open hands that barely touch the reins are just as at fault; although not as uncomfortable for the horse, lack of contact is tantamount to lack of conversation.

For dressage riders, a good hand position is about more than just hands. The position includes the use of the whole arm: elbow, forearm, and shoulder. The arm must be in an L shape, with the elbow bent. If you hand a rider a stack of books and she lifts only her forearm from the elbow and takes the books, she can hold that L-shaped position for a long time. If she extends that arm out from her body, even four inches, she won’t be able to hold those books for very long because her arms will pull her shoulders forward, and she will be unbalanced.

The proper arm and hand position for dressage: the elbow is bent, and the reins are held between the thumb and index finger and the ring finger and the pinkie.

To avoid holding with tension, imagine that your hands are an extension of your elbows. Riding from the elbow forward will keep you from gripping the rein. If you have to get demanding in your conversation (let’s say, for instance, your horse is getting strong and trying to pull the reins away), you can tighten your elbows and prevent her from running through your hands. Even with firm elbows, you’ll still be able to keep those quiet, soft hands.

The dressage rein is held between the thumb and the first and second knuckles of the index finger and passes between the ring finger and the pinkie (held between the first and second knuckles of the ring finger). The thumb creates enough pressure to keep the reins from sliding loose, and each finger stacks evenly on top of the next. In this manner, your sense of touch is much more sensitive than if your reins are held toward the backs of your fingers.

The use of this hand position is very simple. Squeeze your right ring finger against the rein if you want your horse to flex right, and squeeze your left ring finger if you want your horse to flex left. Squeeze one or both reins for a half halt. If you need a stronger aid, say for a sharper turn, think of turning a doorknob. If you want to go right, gently turn your right fist as though you are turning a doorknob to the right. Note: If your horse isn’t responding, check that your reins are the proper lengths. The reins should be short enough to enable you to feel your horse’s mouth.

For hunter and jumper riders, the elbows are held in front of the body. This is because the body position for hunter equitation and jumping has to be more forward. In dressage, with the more upright position, you have the weight of your body to help when using the reins, which gives you more leverage. In jumping, you need a shorter length of rein to achieve the same sort of leverage. Hands should be held an inch apart and an inch above the horse’s crest.

Fingers should be curled inward and closed against the hand in a relaxed manner, and all your fingers should face one another. This position allows the bit to work flush against the horse’s cheek. When your hands are flat and wide, the bit gets pulled away from the horse’s face and does not work as well. Turning your hands down also puts a dead weight on the reins and into the horse’s mouth, encouraging her to lean.

For huntseat, the rider’s elbows are slightly forward and the fingers are curled inward and closed against the hand.

For this hand position, think of using your rein as if your arm were a door: your hand is the knob, your forearm is the door, and the space between your hip and your elbow is the hinge. Your arm and hand (with a straight wrist) together swing around your entire body, moving toward the horse’s hip. This gives you a greater range of motion because you can move your hand from the withers all the way around your body. If you just use your wrist, you have only one or two inches of movement. This is fine in dressage, but when you are jumping a course, you need the ability to make short direction changes faster.

For all disciplines, to keep a soft contact on your horse’s mouth, your hand and arm positions must follow the movement of the horse’s head and neck in each gait. At the walk, your elbows move back as your hips move forward and out as your hips move back. At the trot, the positions remain steady. At the canter and gallop, they move forward and back, along with the motion of your seat.

Riding the Gaits

You may have noticed while lunging your horse that her movements affect the saddle in different ways: the trot makes the saddle move up and down, the canter moves it in a twisting motion, and the walk moves it forward and back. Very simply put, to ride the gaits properly, you must follow these motions with your seat.

The Sitting Trot

In the sitting trot, some horses are very smooth, and their riders don’t have to do much more than sit. Other horses are very bouncy; many riders respond by trying to sit as still as possible, but this never works. The horse is moving so you must move with her. When the horse is in her suspension phase, the sitting trot feels as though you are catapulted up, to a greater or lesser degree depending on the horse; when she comes down from the suspension, you fall back into the saddle. If you are sitting the trot correctly, you learn to absorb that up-and-down movement in your knees, in your hips, and slightly in your ankles. If you brace your leg out in front of you, no shock will be absorbed.

Sit so that your upper body is disturbed as little as possible. Because your upper body is high above the horse, you influence her balance. If your shoulders are flopping from side to side, you may cause her to stagger sideways, which may force her to throw her head up into the air for balance. This is where your core muscles come in. If you flex your back muscles and stomach muscles, you will hold your seat to the saddle.

Try this exercise. While riding in an enclosed space, pick up the sitting trot, and hold the pommel with your outside hand and the cantle with your inside hand (this turns your body in the direction the horse is moving). Alternatively, you can lace a leather strap or the bottom half of an old drop noseband through the D rings of your pommel to create a “cheater” strap. If your horse is calm, tie the reins in a knot, hold them against the pommel, and let your horse follow the arena wall around. It is very important that you don’t grip with your butt, thighs, or calves. If you grip, you are going to bounce because you will be holding yourself down with the wrong muscles. You must use your upper body to press your seat into the saddle. This means keeping your stomach and back relatively still, without tilting forward and back on the pelvis as people often do. Don’t wiggle your stomach, and don’t arch your back and stick your bottom out behind you. Ideally, exert a steady, constant pressure on your seat bones. This technique takes a long time to develop. As you get better, loosen your grip on the strap to teach your back to stay with the saddle. If your horse is trained to go in side reins, you can also repeat this exercise on the lunge.

This is a good position for the sitting trot.

Here a strap of leather has been laced through the D rings of the saddle’s pommel to create a “cheater” strap.

Bouncing is a common theme in the early stages of the sitting trot; the important thing to know is that when you bounce up you’ll fall back down into the same place. You can catch yourself with your knees if you happen to fall sideways, but then relax your knees again so your sitting bones can fall on the saddle. If the horse’s back is properly relaxed and her neck is down, you won’t hurt her. A horse will object, however, if the rider pulls on the reins as she bounces.

Another reason people bounce is that their shoulders are stiff. Learn to relax your shoulders with this exercise. Holding the pommel with your outside hand, swing your inside arm up and back in rhythmic circles, calmly and with a soft shoulder, in time with the horse’s movement. Switch arms, and when you are comfortable, circle both arms at the same time, grabbing the pommel when necessary. A variation on this exercise is the shoulder shrug: lightly holding the pommel with both hands, shrug your shoulders up, back, and around in circles.

While riding on the lunge, learn to relax your shoulders with arm circles, as demonstrated.

For a good back-strengthening exercise, hold your arm up and stretch it back while riding a sitting trot, as shown.

To strengthen your back, pick up the sitting trot, hold one arm up straight, and stretch it back to tighten the back muscles.

By this time, you should be able to pick up the reins; however, check to be sure you are ready. Put your hands in the rein-holding position with no reins, and see if your hands jump up and down. If they do, you need to relax your elbows and shoulders. You can also learn to stabilize your hand by resting the bottom part of the hand on the pommel as you sit the trot. (Note: the hunter rider sits in a similar dressage position while sitting the trot, rather than leaning forward in a two-point position.)

The Posting Trot

The posting trot is an important skill to perfect, particularly since we use it so much of the time. An improved posting trot will give you steadier hands, better control of your leg aids, and a softer seat.

A hunter or jumper rider should lean forward and post forward and backward. In the posting trot, the rider’s shoulders should be inclined slightly forward, about 30 degrees from vertical. At this angle, you can move with the horse’s motion, which in turn allows your horse to trot out better. Hunter and jumper riders also use the posting trot as a tool to get off the horse’s back and allow her to stretch her neck out and forward.

A dressage rider, on the other hand, should sit over the vertical with shoulders and hips aligned. The thighs should hang as straight as possible; the knees should be slightly bent. The shoulders should never lean forward. The hips should rise out of the saddle and forward over the pommel and land back in the saddle in the same place. In this position, the rider is able to keep her lower leg quietly against the horse’s barrel throughout the phase of the posting trot so she can use it when needed. This position also helps the horse arch her frame and encourage her haunches under.

The hunter/jumper rider posts the trot with the slightly forward body angle shown here, about 30 degrees from the vertical.

The dressage rider posts the trot by rising and sitting over the vertical as shown, with shoulders and hips aligned.

The Canter

To ride the canter, let’s look at lunging once more. Think about the motion of the saddle as your horse canters. It moves in a twisting fashion. Your seat must move in a similar twisting way in balance with your horse. Some instructors may urge you to ride the canter with a forward-and-back motion, the way a child rides a rocking horse. This is a good visual for the beginning stages of your riding career, but you’ll need to add another piece of the puzzle at this stage of your skills. The horse’s leading leg will cause the twist to be canted more to one side than the other. Therefore, your inside hip should twist farther forward than your outside hip. Hold your shoulders still and allow your lower back to be soft and move with your horse.

The Hand Gallop and the Gallop

Hand gallop means the horse is still “in hand,” or controllable. Lengthening the stride and slightly increasing the speed is your goal. The hand gallop is used in lower levels of eventing; the speed at Novice is set at canter speed, 375 mpm (meters per minute, the universal unit of measurement for gait speed), increasing to 450 mpm at Training. Jumpers compete above 375 mpm, so this gait is used frequently in competition. The hand gallop also can be used as a schooling exercise for dressage horses to produce a more forward and expressive canter.

In the canter, the rider’s inside hip twists a bit farther forward than her outside hip, with still shoulders and a soft lower back, as demonstrated here.

The hand gallop and gallop positions are very similar to the jumping, or two-point, position. In this position, you no longer sit in the saddle. You take the seat, your third point of contact, away and ride from the heel up to the knee. Looking up and straight ahead will make you a much softer, much more forward rider. The most important concerns are that your hands are low, that the foundation of the position is in your lower leg, and that you’re not using the horse’s mouth for balance.

Hold the reins in the usual way in the hand gallop. In the gallop, hold your reins in either the half bridge or the full bridge. For the half bridge, stretch one rein across the horse’s neck so that you’re holding two pieces of leather in one hand. For the full bridge, stretch both reins across the horse’s neck so that both hands are holding two pieces of leather. The reins will be pulled across the horse’s crest instead of hanging in a loop alongside the neck. The bridges are also very useful tools in terms of safety. If your horse were to stumble, the bridge can keep you from falling because your arms won’t collapse on either side of the horse’s neck.

This is the correct hand position for the full bridge used in a gallop.

This is the correct hand position for the half bridge used in a gallop.

The gallop is the gait at which event riders shine. In fact, most cross-country work is performed at the gallop. Preliminary eventing speed is set at 520 mpm, Intermediate speed at 550 mpm, and Advanced speed at 570 mpm. Knowing how to ride at a specific eventing speed is an important skill. To learn what each speed feels like, set up a meters-per-minute track. You will need a measuring wheel (available at tack stores, hardware stores, or home improvement centers); stakes with flags; and a long, even stretch of ground with decent footing. Measure out the distance on the gallops, and place a stake in the ground for whatever speed you want to learn: 375 meters out from the start of your gallop for the canter; 400 to 450 meters for the hand gallop; 520, 550, and 570 meters for the upper levels. Wear a watch and time yourself from the starting point. You should reach your chosen stake in one minute.

The best way to gallop is to begin slowly and build up to it gradually. This is advisable because some horses get high on the speed, and a fast start can undo the hard work you’ve put into training an obedient horse that listens to your aids. When you’re eventing, leave the start box at a trot, then go into a canter, then a hand gallop, and then the gallop to ensure that your horse is still listening and rideable.

When jumper riders gallop in a class against time, they treat the gallop much the same as the hand gallop, a little bit quicker but not so fast that they knock the fence down. To practice, gallop toward the fence, and then slow down or “balance up” a few strides in front of the fence to allow your horse to get her legs underneath her to jump.

Galloping requires a lot from a horse, and she can injure herself badly if her body isn’t used to concussion at top speed. Think long and hard about whether galloping is right for you and your horse. The once-a-week rider should not gallop: galloping is for people who ride their horses five times a week. If you think galloping is for you, you must work up to it by conditioning your horse. Most event riders gallop once every five days, but your horse may not be up to this schedule. Warm up with ten to twenty minutes of trotting, then begin with three minutes at the hand gallop, two minutes at a walk, and another three minutes at the hand gallop. Then, after a few weeks or months (consult a trainer if you are unsure how to test your horse’s fitness level), progressively increase the gallop speed to 450 mpm for three minutes, followed by the two-minute walk and then the second gallop at 500 mpm for three minutes. This interval training builds your horse’s cardiovascular system and soft tissue.

You should also outfit your horse in the appropriate bit for galloping, one that gives you adequate control. For some horses, this might be a simple snaffle; for others, it might be something stronger. A flash or figure-eight noseband is important because it ensures the horse will keep her mouth closed, which will also help you maintain control. If the horse’s mouth is open, no bit will work. Your horse should also be wearing brushing boots for protection. Polo wraps can come undone or slip, and a horse can trip or fall if she steps on a loose wrap.

Refrain from galloping in wooded areas. It’s hard to gauge your speed and see what’s ahead or coming at you in the other direction. Before you gallop, walk the area to check for holes and debris and to make sure the ground is not too hard, deep, or slippery. Understand that your speed (when you’re practicing) will depend on what the land and conditions allow. You can turn only so sharply or go downhill safely at only certain speeds. As you go faster, the balance of the horse should always stay the same.

This horse is properly equipped for galloping, with a flash noseband on the bridle and brushing boots on the legs.