Читать книгу Advanced English Riding - Sharon Biggs - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRiding Within the Gaits

Riding in the beginning stages is all about the working walk, the trot, and the canter, but as you advance in your skills, everything becomes more complex. For instance, you must learn how to move seamlessly from one gait to another. You need to include paces in your repertoire; for instance, the walk paces include the free walk, the medium walk, the extended walk, and the collected walk. While jumping, you must learn to adjust your stride within the speed of your canter, hand gallop, or gallop, depending on the style of fence. Advanced riders also need to learn how to advance a horse’s knowledge with a method of training. In dressage, this is primarily the training pyramid or scale. Because this is a universal, integral concept among riders of all disciplines, I urge you to incorporate this technique into your own training sessions.

Transitions

A well-ridden transition seems a simple thing. After all, in essence you are only switching gears: walk to trot, trot to canter, or trot to walk. But many things that appear easy are in actuality very hard to do. What people see in that easy transition is a horse that smoothly changes rhythm; for example, from a one-two, one-two beat in the trot to a one-two-three beat in the canter. Nothing else changes: the horse should continue to move forward with the same energy (unless you’ve halted), remain on the bit or accepting the bit, and stay balanced. But what brings about the shift in gaits is indiscernible to observers. That’s the rider’s job, to make his aids invisible to spectators and obvious only to the horse—to make the whole thing look easy. A great transition is one that is prepared and well trained, but most of all one that shows the true harmony and partnership between horse and rider that has developed over time.

If you’re a dressage rider, bad transitions will keep you stuck in Training Level because the further you advance in the levels, the more important transitions become. If you’re a hunter or jumper rider and you can’t pull off a transition on the flat, you’ll be in trouble when it comes to jumping because you won’t be able to gauge your distances. You’ll come into the fence too deeply or chip in an extra stride. Your hunter won’t make the proper strides between fences, and your jumper will most likely pull rails.

A common fault in the downward transition is that the rider leans back and braces against the horse and uses his stirrups as brake pedals. Or he leans forward and lightens his seat. Because there is no preparation, the result is an awkward transition, or the horse either braces back and ignores the rider completely or responds by going faster. When riders brace and fall to the back of the saddle, their seat drives the horse on and makes her go faster. Everyone instinctively leans back to stop, and that’s good if you’re a beginning rider and you’re going to fall off, but not at this stage in your riding. The answer is to keep your position through your transition.

Using the bit for a brake is another common fault. If this is your issue, go back and review your half halt and make sure you are applying it correctly.

Making an upward transition by chasing the horse until she reaches the required gait is also a common error. For example, instead of simply moving from the trot to the canter, riders gun the horse forward from the walk to a fast trot and then to the canter. In this error, the rider’s seat has shifted too far forward, and he has not started with his horse balanced and accepting the bit. In the upward transition, keep the energy flowing from behind. Ask when your position is correct, and don’t ask for the canter if your horse begins to run. Bring her back and try again, this time with better preparation. You may have also used too sharp an aid to jolt your horse forward. Ask with a softer cue.

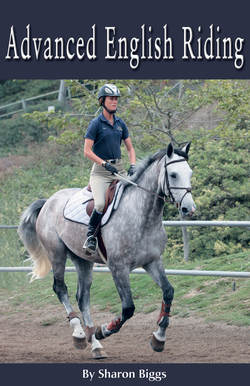

This balanced rider has her horse moving in a controlled canter, ready for a smooth downward transition.

If your horse doesn’t respond to the upward transition, chances are she’s ignoring your aids. Instead of beating a tattoo against your horse’s ribcage, reschool her to a light leg aid. Bring your horse back to the walk, and ask her to trot on. If she won’t go, pair your leg aid with a touch of your whip. If she trots on, pet her and bring her back to a walk. Then ask again with a lighter aid, turning up the volume with your whip until you can put your leg on lightly and she will trot off.

A rule of thumb for hunter and jumper/riders: If your horse is rushing and dragging you to the jump, go back and work on your transitions from the canter to the trot. If your horse is too slow and you feel that you keep getting left behind at the jump, make sure your canter departure from the walk is correct.

The Training Pyramid, or Scale

The training pyramid (also called training scale) is an important concept in dressage training. Failure to understand the dressage pyramid when training or not taking each step into account is a very common rider error. The dressage pyramid is a logical training method: each new step builds on the previous step. It begins with rhythm, followed by looseness, contact, straightness, and impulsion and ends with collection. Skip one criterion, and you won’t be heading up the scale and will have difficulty advancing.

Rhythm: A pattern of steps or strides for each gait, such as the one-two-three in the canter and the one-two, one-two in the trot. The beat should be regular, and each pattern should cover equal ground. To achieve a good rhythm, your horse must be free from any soundness issues and must be able to carry the rider while staying balanced.

Looseness: Physically and mentally free from tension. The horse accepts the rider’s aids and moves forward correctly at the tempo (speed) that the rider requests.

Contact: The horse moves forward toward the bit without apprehension or fear of the rider’s hands. (See chapter 4, Putting Your Horse on the Bit.)

Straightness: The forehand is in line with the hindquarters, and the horse’s weight is evenly distributed on both sides. If your horse is not straight, you will have trouble turning, making circles, and doing lateral work. You can feel the straightness in the ease of accomplishing all of the above.

Impulsion: Thrust or pushing power of the hind legs in the trot and the canter (the walk has no impulsion because it has no moment of suspension). The horse pushes herself through the arena instead of pulling with her front legs. With impulsion, you feel the horse taking a bigger step as you apply your legs. The gait feels stronger and more purposeful.

Collection: Increased bend of the hind legs, with the horse carrying more weight on the haunches and less on the forehand. The horse’s movements are easier to ride. (See the following section.)

Collection

When a horse is collected, she brings her hind legs farther underneath her body and carries more weight in her haunches. The working gait does not require the horse to do this. The working gait also lacks a certain amount of impulsion and engagement of the hind legs. Riders often mistake collection with riding very slowly, but in truth the tempo alters very little. The horse’s neck must not get shorter; in fact, it won’t change in length through the dressage levels. Instead, the horse’s outline will be more uphill because her front end will rise as she takes more weight back onto her haunches. Some of the hallmarks of collection are the ability to ride movements with ease and smooth and steady transitions.

This upper-level dressage horse performs the piaffe, one of the highest demonstrations of collection.

At the early levels of collection, there is only a slight difference between working and collected gaits. The collected trot you see at the lower levels is a different collected trot from that seen at Grand Prix because the horse is stronger at the higher levels. At the higher levels, collection is highlighted in advanced movements such as piaffe and passage. At the lower levels, it is demonstrated in movements such as shoulder-in and the extended gaits.

Strengthening exercises are helpful for collection. Ten-meter circles engage the inside hind leg and develop the muscles. Transitions work to develop the all-important impulsion or thrust from the hindquarters required for collection. Too much work in collection can be tiring, so keep your workout appropriate to your horse’s level of training. And always end your sessions with a stretching circle.

Ride a ten-meter circle to engage the inside hind leg and develop the muscles of the hindquarters, as shown.

Extensions

Many riders are confused about what constitutes an extension. An overstride in the medium and extended walk is a requirement in the dressage tests, but how much overstride is inconsequential; judges take into account the horse’s breed, confirmation, and ability. Clarity of the rhythm, elasticity to the walk, and whether a horse moves over his topline are more important. In the trot, the horse ideally should step over the prints of his front hooves. In the canter, the horse must cover more ground.

The Extended Walk

Pay special attention to the walk because it is the easiest gait to ruin and the most difficult to correct. The extended walk paces include the free walk, the medium walk, and the extended walk. In the free walk, the horse is allowed to lower and stretch the head and neck on a loose or free rein. The medium walk should have an overstride, and the horse should stretch to and remain on the bit. In the extended walk, the horse covers more ground and stretches the head and neck out while still maintaining contact. All the walk paces should march forward with good energy and have a purity of rhythm.

In dressage competition, the walk is valuable. For instance, there are fifty points related to the walk in many of the Training and First Level tests, which incorporate the medium walk, the free walk, and the gaits scores. The free walk score is doubled. The points for the walk are high because the gait is an indicator of the quality and progress of training. A walk that becomes impure in any way or is a little uneven because of crookedness or resistance can hurt the submission score as well.