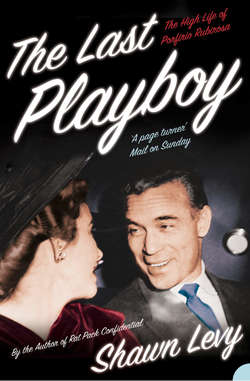

Читать книгу The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa - Shawn Levy - Страница 10

FIVE STAR POWER

ОглавлениеOn the one hand: liberty.

In divorcing Flor, Porfirio had unchained himself from an anchor, but he had also let go of a lifeline.

Yes, she behaved prematurely like an old Dominican dama with her petulant whining about his carousing and his other women, refusing to accept him for the type of man he was.

But: As the daughter of a powerful man, she was a direct conduit to money, security, and stature—and perhaps, given Trujillo’s incendiary nature, life itself. Losing her meant unmooring himself totally from the life he’d known since boyhood, a life implicated in the political goings-on of his homeland.

He lost everything. Before long, dunning letters began arriving at the Dominican embassy in Paris—saddleries and purveyors of equestrian clothing looking for payment on items he’d bought with a line of credit he no longer commanded.

By then, at any rate, he was no longer, technically, an embassy employee. Trujillo had expelled him from the diplomatic corps in January 1938. Virgilio, the generalissimo’s resentful older brother, managed to secure him a temporary appointment as consul to a legation that served Holland and Belgium jointly, but that expired by April. He held on to his diplomatic passport and was occasionally seen around Paris in embassy cars, but he was, literally, a man without a country. He wasn’t about to go home to the Dominican Republic, where his prospects for work were no better than in Europe and his prospects for play considerably worse. Plus, he had already heard from his mother not to risk the trip: Trujillo wanted his head; Paris was decidedly safer.

He was certain in his own mind that Flor hadn’t instigated her father’s fury. Indeed, he would declare that he always harbored warm feelings for her: “After this romantic catastrophe, we stayed good friends.” (They were widely said, in fact, to reignite their sex life whenever Flor, who’d apparently overcome her initial aversion to his lovemaking, was in Europe.) “And,” he continued, “I followed, with friendship, her life.” With friendship and, no doubt, amazement: after divorcing Porfirio, Flor would go on to take another eight husbands, including a Dominican doctor, an American doctor, a Brazilian mining baron, an American Air Force officer, a French perfumer, a Dominican singer, and a Cuban fashion designer. She had a short heyday as a diplomat in Washington, D.C., but during long periods of her life her father disowned her and even had her held under house arrest in Ciudad Trujillo. She would eventually come to dismiss her first husband with a shrug, answering interviewers who asked whether he was handsome or charming with a curt “For a Dominican.”*

And so what to do?

Another man might assess the situation and reckon it was time to think about settling down in France: a wife, a job, kids, a house, responsibility.

Not a tíguere, not with this sort of freedom, not at this time, in this place, with this thrilling sense of possibility and a titillating sense of impending catastrophe. “I was a young man in a Paris that the specter of war had heated up,” he remembered. “I lived a swirling life, without cease, without the pauses that would have allowed me the chance to think and make me realize that giant steps aren’t the only strides that suit a man.”

He spent time at Jimmy’s, a Montparnasse nightclub run by an Italian whose real name too closely resembled Mussolini’s to make for good advertising and who therefore took an American name as a PR maneuver. There, the comic jazz singer Henri Salvador became a friend. Porfirio sat in with his band for late night sessions—his little skill on the guitar and enthusiasm for drums were fondly received—and led parrandas of the musicians and clubgoers late into the night, retiring to this or that partyer’s flat for bouts of drinking and merrymaking that could last until the middle of the next day.

Of course, this sort of traveling circus required funding, and, as its ringmaster no longer enjoyed legitimate work as a diplomat, other strategies emerged. There was the familiar one of living off a woman. La Môme Moineau, the singing, yachting wife of Félix Benítez Rexach, was in Paris and available to him once again as her husband was off earning millions on his various projects in the Dominican Republic. Now, however, she had a fortune to spend on and share with her lover; he drove around the city at various times in one or another of her little fleet of luxury cars; occasionally, he would raise cash by selling off some valuable bijou from her jewel case.

This character—nightclubber, cuckolder, kept man, gigolo, scene maker, skirt chaser, dandy—was not so much a new Porfirio as an evolved one. Nearing thirty, freed of father, wife, and father-in-law—the living connections to his homeland that had thus far defined him—he was no longer an exotic, a Dominican in Paris, but, more and more, a Parisian with intriguingly Dominican roots. He had been an enthusiastic regular in the demimonde; now he was a staple of it. And, free of the constraints of decorum that adhered to him as the son of Don Pedro or the son-in-law of Trujillo, he no longer required so formal and elaborate a name as Porfirio Rubirosa. Anyone who knew him, truly knew him, in Paris after his divorce or, indeed, for the rest of his life, knew him as Rubi. Even more than his mellifluous given name, which he still used to dramatic effect and for official purposes, this new moniker captured his mature essence: the jauntiness, the rarity and high cost, the sparkle and the sharpness and sensuality and the bloody, cardinal allure.

Especially, perhaps, the bloody allure.

Over the years, he would—by virtue of his high living, his obscure origins, his association with Trujillo, his love of thrills and danger—almost inevitably be associated with shadowy events. Most of it was idle gossip. In some cases, such as the Bencosme murder, there were real reasons to think he was involved, albeit peripherally.

And then there was the matter of the Aldao jewels and Johnny Kohane.

For all the munificence of La Môme Moineau, Rubi wasn’t satisfied with his solvency. The life to which he aspired required real capital. He needed a score. In early 1938, while he was still holding, despite Trujillo’s injunctions against him, a diplomatic passport and temporary consular position, Rubi became involved in a scheme to smuggle a small fortune in jewels out of Spain. The goods in question belonged to Manuel Fernandez Aldao, proprietor of one of the most esteemed jewelry establishments of Madrid. In November 1936, when the Spanish Civil War had so turned that Madrid was under siege, Aldao had fled for safety to France and left a good deal of his wealth behind in the form of a safe filled with jewels guarded by an employee named Viega. Two years later, Aldao had need of his resources but was unable to retrieve them himself. He came into contact with Rubi, perhaps through Virgilio Trujillo, and hired him to go to Madrid and use his diplomatic pouch to transport a cache of jewels—and an inventory describing them—back to Paris.

In the time it took for the details of the operation to be worked out, another errand was added to Rubi’s schedule and another conspirator to the plot: Johnny Kohane, a Polish Jew who had also fled Spain without his fortune (some $160,000 in gold, jewels, and currency, he said), was introduced to Rubirosa by Salvador Paradas, who’d replaced him at the Dominican embassy. Kohane had need of his stash, and it was agreed that he would join Rubi on the trip using a passport borrowed from the Dominican embassy chauffeur, Hubencio Matos. In February, the two would-be smugglers got into the embassy’s Mercedes and drove across southern France and, through the Republican-controlled entry point of Cerbere-Portbou, into war-ravaged Spain.

A dozen days later, Rubi returned—alone.

He handed a sack of jewels over to Aldao—a smaller one than the Spaniard expected—and claimed that he’d never been given any inventory to go with it. And he told a hair-raising story about the bad luck he and Kohane had run into outside of Madrid when they were off fetching the Pole’s fortune. They were set upon, he said, by armed men, he wasn’t sure from which side, who chased them and shot at them, killing Kohane. He was lucky, he said, to get out of there with his own skin intact.

What could anyone say? He’d had the moxie to go get the jewels and to get back in one piece. As for Kohane, it was a war zone; he knew it was a dangerous proposition going into it. Suspicion was natural. The car in which Rubi claimed to have been ambushed evinced not a single scratch. But there was no tangible proof that the story, however far-fetched, wasn’t true. Aldao paid Rubi his agreed-upon fee—a platinum-and-diamond brooch—and stewed over the matter for years.

When the situation in Spain finally settled and it was safe to cross back through France, Aldao returned home and looked into the matter of the half bag of jewels and the missing inventory. He wasn’t pleased. There had been an inventory, and Viega had handed it to Rubi; a carbon copy of the original document still sat in the company safe. What the inventory showed was that the bag that left Madrid held jewels worth some $183,000 that never made their way to Aldao in Paris. What was more, a fellow who’d been enlisted to help the Mercedes cross the border swore that he’d never received the platinum-and-diamond bracelet that Aldao had instructed Rubi to give him.

Aldao wrote Rubi in Paris several times to inquire about the missing items but was repeatedly ignored. He sent a Parisian friend to confront Rubi and, as he later declared, his emissary was rudely rebuffed: “The result of the meeting was completely negative, and he was moreover very discourteous to my friend.” Finally, a few years after the fact, he wrote a letter of formal protest to Emilio A. Morel, the Dominican ambassador to Spain. It wasn’t the first Morel had heard of the case—an anonymous letter had found its way to him a year or so earlier, a note, he recalled as so “crammed with inside information” that he believed its author was “a compatriot of Rubirosa’s, actually a principal in the smuggling plan, who felt he had been double-crossed out of a commission from Kohane and took this method of seeking revenge.” Morel dutifully sent notice of these claims against Rubi to the Secretariat of Foreign Relations in Ciudad Trujillo; not only were his inquiries sloughed off, but he, a noted Dominican poet and onetime leader of Trujillo’s own political party, found himself, by virtue of making them, suddenly in the bad graces of the generalissimo. He left Madrid for New York, where he lived out his years in exile. And Aldao got nothing.

Rubi likely had the jewels—and all of Kohane’s assets as well. His finances seemed to have worked themselves out for the decided better. He had been so skint at the start of the year that he would on occasion feign illness so as to summon friends to his house with restorative meals—the only food he could, apparently, afford. After returning from Madrid, however, he spoke of opening his own nightclub and renewed his habit of forming an impromptu club wherever he went; the genius guitarist Django Reinhardt was soon among the players in his ever-expanding, never-ending, ceaselessly moveable feast. Deauville; Biarritz; the French Riviera; and all through the Parisian night: He was ubiquitous, a star. Old friends who encountered Rubi in Paris—among them Flor de Oro and his brother Cesar, now himself a cog in Trujillo’s diplomatic machine—found him exultant, even though they’d been led to expect he’d be sporting a more destitute aspect.

Perhaps news of his self-made success made it back to the Dominican Republic, perhaps he was vouched for by Virgilio Trujillo, but in the spring of 1939, the most amazing bit of fortune landed in his lap: a phone call from Ciudad Trujillo. “The President, who is beside me,” said the official on the other end, “would like to know if you could see after his wife and son, who will arrive in Paris in a few weeks. You’ll have to find a house of appropriate size, accompany them, show them around.”

“I was so stupefied,” Rubi remembered, “that I couldn’t answer straightaway. At first I wondered what sort of trap it was. I couldn’t see one.”

He hurriedly made arrangements to receive Doña Maria and ten-year-old Ramfis and met their boat in Le Havre, where he was startled to find the president’s third wife a full eight months pregnant. Rubi immediately arranged for her to be taken to a clinic where, in comfort, she gave birth to a daughter, Angelita, on June 10.*

In the weeks before and after the birth, Rubi engaged in a full charm offensive, presenting Doña Maria with gifts of jewelry (booty, no doubt, from the Aldao collection) and seeing that the awkward, friendless, unschooled Ramfis was kept happy; the two rode horses together, and it was likely around this time that they began tinkering at polo. As Rubi recalled, the campaign was a success: “Doña Maria wrote to her husband that I was useful, attentive, charming and courteous. Was it due to the sentiment that accompanies pregnancy? Was it due to the change of nations and distance? Trujillo warmed to me.”

The Benefactor had come to recognize that in Rubi he had a truly unique asset: a young, handsome, worldly, cultivated Dominican of notable suavity and negotiable loyalty. Doña Maria, who had no history with the young man, must have impressed her husband with tales of his social skills and tact. And, as Trujillo was soon to discover himself, no Dominican was as enmeshed in the manners and mores of the great European capitals than his scalawag former son-in-law.

The dictator made a grand official tour of the United States in the early part of the summer and then wrote to France to announce that he would be joining his family there. He had his yacht, the Ramfis, sent ahead to Cannes and then sailed to Le Havre himself aboard the Normandie. Rubi was at the dock to meet him. “In the place of a furious father-in-law and an autocrat exasperated by my impertinence,” he recalled, “I found a friendly and agreeable man.”

Trujillo wanted to see the grand sights of Paris—“the elegant Paris, without beans and rice,” as Rubi remembered. But he was perhaps even more interested in the louche part of the city that his former son-in-law, unique among Dominican expatriates, could show him. “Porfirio,” he pronounced, “do not leave my side. I want you to show me everything. You understand? Everything.” Everything included a trip to the top of the Eiffel Tower, where the generalissimo fell under the spell of a girl selling flowers and postcards (presently he courted and bedded her, Rubi remembered, “because he wanted to seduce the loftiest woman in Paris”—“loftiest,” geddit?). The visit included nights out at Jimmy’s, where the generalissimo, unusually in his cups, declared, “We need a Jimmy’s in Ciudad Trujillo, but much bigger, with four orchestras, gardens and a patio open to the sea.” They moved on to Biarritz, where Trujillo expressed a similar desire to re-create the local hot spots back home. And finally the entire Trujillo party relocated to Cannes and a Mediterranean cruise—all the way to Egypt, they hoped—at the launch of which the dictator whispered to his guide, “Porfirio, I am putting you in charge of this entire voyage.”

But it wasn’t to be. The war that Rubi hadn’t foreseen when he was sitting within a few feet of its architect in a Berlin stadium began in earnest. And although the Dominican Republic was still officially neutral in the boiling European conflict, events in the Old World seemed likely to upset the balance of power in the Caribbean. Trujillo felt he had no choice but to leave Doña Maria and the children in Rubi’s care and sailed home on the Ramfis. By the time he reached Ciudad Trujillo, Rubi had safely sent his family after him.

If Trujillo felt cheated out of his grand tour, Rubi was handsomely rewarded for the part he played in orchestrating it. Back in the dictator’s good graces, he was reinstated at the French and Belgian embassies as a first-class secretary.

It was a truly auspicious time to hold such a position. Trujillo, still stung by the beating his image had taken after the Haitian border massacres, had made a grand show of opening his country to refugees from the Spanish Civil War; it wasn’t a huge influx, but the PR bounce was good. When he became aware of the desire of European Jews to relocate to the Western Hemisphere, he saw an opportunity to ingratiate himself with U.S. interests. Although he reckoned Judaism to be synonymous with communism, he declared that the Dominican Republic would accept one hundred thousand European Jews on its soil and demarcated a territory where they would be allowed to settle: Sosùa, a beachside village on the northern coast; a large parcel of his own land would be given over to the enterprise.

Word that Trujillo was accepting Jewish refugees led to a run on Dominican consulates and embassies in countries not yet controlled by the Nazis. A chancer like Rubi, given access to papers that could liberate anybody he favored, was sitting on a gold mine. He sold visas on a sliding scale, getting as much as $5,000 a head, and never concerned himself with how or even if his customers got out of France, much less all the way to the Dominican Republic. As it happened, Trujillo’s offer was chiefly rhetorical: Fewer than one thousand European Jews made their way to Sosùa, and the projected Caribbean Jerusalem eventually became a resort with a little Jewish history sprinkled in.* But from the vantage of Paris, it didn’t matter: Rubi did a thriving business until the Nazis took the French capital. “He got rich selling visas to Jews,” shrugged his brother Cesar. “Didn’t everybody?”

The business wasn’t always pernicious. A Spanish journalist who feared Fascist reprisals against him managed to get a visa out of Rubi for free but had to pay him $5,000 for transport from Paris to Barcelona to Puerto Plata, where a train would take him to Ciudad Trujillo. “When I got to Puerto Plata I learned that there had never been a train from there to Ciudad Trujillo,” he recalled with laughter.

And sometimes the results were profound. Take the case of Fernando Gerassi, a Turkish-born Spaniard who came to Paris in the 1920s and, as an abstract painter in the mode of Kandinsky and Klee, chummed around with such Left Bank icons as Picasso, Sartre, and Alexander Calder. By the late 1930s, Gerassi had fought for the losing side in the Spanish Civil War and found himself living back in Paris under the uncomfortable threat of German ascendancy. And then he had a chance meeting with somebody who could help. According to Gerassi’s son, historian John Gerassi, the painter and Rubi met playing poker and hit it off and Rubi was able to help his new friend by hiring him as a secretary at the Dominican embassy. Then, when the Nazi threat grew more intense, he gave Gerassi a more prestigious title that resulted in safe passage out of Europe not only for him and his family but, as it turned out, for many others.

“My family was leaving Paris because the Germans were coming,” the younger Gerassi recalled. “Rubirosa gave Fernando the position of ambassador from the Dominican Republic, gave him the official stamp. Fernando, in turn, gave eight thousand passports to Spanish Republicans, Jews, whoever he could help, before the Germans caught up. My parents came to America as Dominican diplomats.” Not only did Fernando Gerassi save the lives of his family and the thousands for whom he obtained visas and passports throughout 1940 and 1941, he was, when the United States entered the war, enlisted in the OSS as an operative in Latin America and then Spain. In the latter operation, Gerassi engaged in disruptions of German military traffic, abetting the Allied landing in Africa and receiving commendation and a medal from the U.S. government. “Without your actions in Spain in 1942,” OSS founder William Donovan wrote to Gerassi, “the deployment of Allied troops in North Africa could not have taken place.” Thousands saved, Nazis frustrated, a painter become a humanitarian hero, and all because Rubi found lucrative use in the black market for his Dominican diplomatic privileges. It’s a Wonderful Life with an ironic coating of avarice.

It wasn’t long, though, before larger events scuttled Rubi’s get-rich-live-rich scheme. Starting in June 1940 when the Nazis finally did enter Paris, the status and even the location of the Dominican embassy shifted with disconcerting regularity. The Dominican Republic was still technically neutral in the European war, and it maintained diplomatic relations with the Nazis’ puppet government in Vichy, a liaison that was difficult to maintain as the Germans continually forced the Dominicans to relocate their base of operations: Twice before midsummer the embassy moved, first to Tours and then to Bordeaux, where Rubi was ordered to present himself. “A lady friend accompanied me,” he remembered in his memoirs, failing to mention that it was his partner in greed, lust, and social climbing, La Môme Moineau. “Officially, the Dominican legation was put up in a castle near St. Emilion. I presented myself there. It was filled with refugees—some crying old ladies, children with dirty noses, caged birds, kittens in baskets, and old men who had saved France in Les Esparges or Verdun.” This wasn’t exactly the duty he’d signed up for, and he immediately took advantage of the vacuum of authority—communication with Ciudad Trujillo had slowed to almost nil—and changed his and his companion’s situation: “I stayed in a pension for a few days and then returned to Biarritz.”

Eventually, a Dominican embassy was established in Vichy. Even though it enjoyed a prime location—it was situated in the Hôtel des Ambassadeurs directly across from the Grand Casino—the new embassy wasn’t to Rubi’s liking. “In Paris,” he explained, “life had recommenced. I was neutral. I returned to Paris and then went to Vichy. Paris—Vichy, Vichy—Paris: This was my itinerary during the fall of 1940.”

And so it was that when the French diplomat Count André Chanu de Limur invited him to a cocktail party in Paris that autumn he was available to attend. Truth be told, he might have made the effort to be there no matter where he’d been when he got the invitation: The guest of honor was just the sort of woman he would want to meet: the highest-paid movie star in France, “the most beautiful woman in the world,” as she was billed, twenty-three-year-old Danielle Darrieux.

At fourteen, there was a knowing depth to her eyes, and their audacity drew you to her soft, gamin face. By seventeen, she could play ten years older than she was and had learned how to steal scenes with such mature tricks as slowly unfurling her eyelids when asked a question. She was a bona fide natural, able to channel emotions—joy, sorrow, worry, hope—in such a way that the audience felt them instinctively through her. But she was at her best as a comedienne, with a delicious ability to squinch her features into a smile so that her eyes seemed two merry commas on either side of the aquiline exclamation mark of her nose.

She was a war baby, born in Bordeaux on May 1, 1917, to Dr. Jean Darrieux, a French ophthalmologist and war hero, and his wife, an Algerian concert singer. (Polish and American roots were hinted at in publicity biographies.) After the Armistice, her family relocated to Paris. By the age of four she was playing piano; later, she would take up the cello seriously. But her path toward the conservatory was hindered by two fateful events: In 1924, her father died, leaving her mother to raise three children with whatever income she could earn as a vocal instructor; and in 1930, Danielle was recommended for a screen test. “My mother was distrustful,” she recalled later. “At that time, the cinema was reputed to be a completely depraved world.” But she nevertheless relented and allowed the girl to go.

Danielle auditioned for director Wilhelm Thiele, one of those Viennese maestros so stereotypical of the silent film era: autocratic, high-minded, and lecherous (a few years later, he would pick Dorothy Lamour out of a chorus line). The film he was casting was based on Irene Nemirovsky’s novella “Der Ball” about a teenager whose social-climbing parents plan a grand ball but don’t include her; jealous, she tosses all the invitations into the river. To deal with the vagaries of the new technology of sound film, which still lacked the capability for dubbing dialogue, Thiele employed the then-common practice of shooting two versions at once—a German and a French, with distinct casts made up of actors from each country. Danielle got the part of the headstrong daughter in the French version.

The impression she made was strong enough to guarantee her a full five-year contract. In the next three years she made nine films, mostly comedies in which she appeared as a sparkling ingénue. (She made one crime film, Mauvaise Graine [“Bad Seed”], which was cowritten and codirected by Billy Wilder.) And she appeared on the stage in several productions throughout Europe: in Paris, Brussels, Prague, Sofia, Munich, and, fatefully, Berlin, where, in 1934, she signed a contract to make six films.

The first film covered by that agreement was L’Or dans la Rue (“Gold in the Street”), the French-language version of a German thriller coauthored by a German named Hermann Kosterlitz and a Frenchman named Henri Decoin. It was a fateful meeting of star and writers. Kosterlitz was a Jew who had engaged in a few unwise run-ins with German authorities and would soon be leaving for America, where, as Henry Koster, he would hit paydirt as the man who made Deanna Durbin a star and put Abbott and Costello in the movies; he would keep a savvy eye on Danielle as her star rose. Decoin was a former Olympic swimmer, World War I pilot, and knockabout journalist who had been working as a director and screenwriter for almost a decade; he would become, in 1935, Danielle’s first husband.

The age difference may have raised eyebrows—he was thirty-nine, she just eighteen—but it made sense when Danielle’s fatherless adolescence was taken into account. As she remembered tellingly, “I was always absolutely confident in him, and I obeyed him in all things.” More striking was the way in which they wed their careers, turning them into one of those classic director-actress couples who do their best work together. In a span of seven years starting in 1935 with Le Domino Vert (“The Green Domino”), Decoin directed his wife in six features, establishing himself as a capable hand in a variety of genres and cementing a directorial career that would last into the 1960s.

But Danielle became an international star largely on the work that she made between Decoin’s films; while he worked exclusively with her during this period, she made more than twice as many pictures without him. He gave her the confidence to take on meaty dramatic roles, and she did so brilliantly. The key step in her ascent was the romantic lead in Mayerling