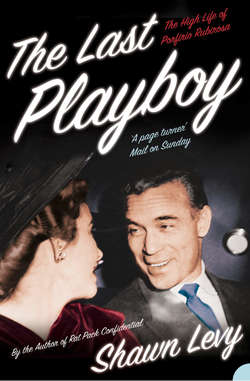

Читать книгу The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa - Shawn Levy - Страница 8

THREE THE BENEFACTOR AND THE CHILD BRIDE

ОглавлениеHis uniforms were always immaculate, as were, when he could finally afford them, his hundreds of suits.

His manner careered unpredictably from obsequious to civil to icy.

His appetites for drink, dance, pomp, and sex were colossal.

His capacity for focused work seemed infinite.

He was a finicky eater.

With his thin little mustache, he looked a cross of Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux and a bullfrog, always with his hair slicked back, always standing erect to the fullness of his five feet seven inches, always tending slightly toward plumpness (as a boy, he was mocked as Chapito: “little fatty”).

He had a massive ego that sat perilously on a foundation of dubious self-confidence.

He remembered everything and forgave nothing, though he might wait years to avenge a grudge.

He wasn’t above physically torturing his enemies and throwing their corpses to the sharks, but he had at his disposal more insidious schemes that involved anonymous gossip, public shunning, and other shames that cut deeper, perhaps, than any punishment his goons might mete out.

His scheming and brutality and cunning and shamelessness and greed and nepotism and cruelty and gall and paranoia and righteousness and delusions of grandeur verged on the superhuman.

He was one of the most ruthless and reprehensible caudillos, or strongmen, ever to hold sway in the Western Hemisphere—and one of the most enduring.

He was Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, and he formed an unholy bond with Porfirio Rubirosa that would crucially shape the latter’s life.

Trujillo was born in October 1891, the third of eleven children of a poor family from San Cristóbal, a provincial capital in the dusty south of the island. The town began as a gold rush camp, then settled into a long, hard haul as one of the island’s many centers for processing sugarcane. It was never an illustrious spot, but for several decades of the twentieth century, it was known by federal decree as the Meritorious City, simply because it was the birthplace of this one man.

By his sixteenth birthday, with only a grammar school education, Trujillo was working full-time as a telegraph operator—and perhaps doing a little cattle rustling on the side, though records of his activities in that sphere would one day disappear. (Likewise, he was convicted of forgery and at another time suspected of embezzlement, but in neither case could it be shown on paper after he’d established his domain over the nation and its historical records.)

By his twenty-second birthday Trujillo was married to a country girl named Aminta Ledesma who was pregnant with a baby daughter who would die at age one and, like her father’s criminal record, be erased from later accounts of his life. A second daughter, with a grander future, came the following year. They named her Flor de Oro—“golden flower” in English, “Anacaona” (the name of a warrior chieftainess of the Jaragua tribe) in the native Taino.

Trujillo first engaged with the hair-raising brand of Dominican politics in the mid-1910s, when he joined an unsuccessful rebellion against one of the nation’s fleeting governments and had to live on the run in the jungle until finally, ragged and starving and underfed and missing a few teeth, he threw himself on the mercy of the authorities. Granted amnesty, he came back home and turned to crime, as a member of a gang called the Forty-four. And then he found honest work in a sugar refinery, first as a clerk and then, providentially, as a security guard.

It was no rent-a-cop position. In the lawless Dominican Republic of the era, the policía of a thriving private business constituted, in many cases, the only local authority of any standing. These forces were charged with keeping the peace and guarding their bosses’ property from theft, but they also fought fires in the cane fields, protected payrolls, made sure workers didn’t defect to rival operations, and mounted and supervised such profitable side businesses as bars, brothels, and weekly cockfights.

It was a position that called for a calculating mind composed of equal parts soldier, accountant, psychologist, and mafioso. Trujillo was perfect for it.

He liked the work so well, in fact, that he decided to become a career soldier, applying at the end of 1918 to join the National Police, the only military force open to a Dominican during the American occupation. His letter requesting induction was a combination of bootlicking, braggadocio, and bald-faced lies: “I wish to state that I do not possess the vices of drinking or smoking, and that I have not been convicted in any court or been involved in minor misdemeanors.”

He was accepted, enrolling as a second lieutenant in January 1919. Within three years, he had attended an officers training school and been promoted to captain. The Yankees liked him: “I consider this officer one of the best in the service,” wrote one evaluating officer. And he continued to advance, sometimes in shadowy fashion. In 1924, the major under whom he served was killed by a jealous husband; most onlookers assumed that the offended party was put onto the scent of his wife’s affair by Trujillo, who eventually replaced the dead man in rank and duties. By the end of that year, with the North American marines having returned home, Major Trujillo was third in the chain of command of a military force that was virtually unopposed in ruling the land.

All that remained now was to take over.

But before he could ascend to full power, there was a domestic matter to resolve: namely, the peasant girl he had married, hardly a fitting wife for a man of his status. Sexually, Aminta had long since been replaced by a string of women, one of whom, Bienvenida Ricart, Trujillo had singled out as a likely next wife. Divorce by mutual consent was, curiously, legal in the almost homogeneously Catholic Dominican Republic at the time, and in September 1925 the Trujillos’ marriage was dissolved by civil decree. Trujillo was ordered to pay alimony, to provide Aminta with a house, and, to his frustration, to leave Flor de Oro to live with her mother—a detail he would revisit.

A full two years later, serving at the rank of brigadier general, he married Bienvenida. But by then yet another concubine had taken a special place in his heart: María Martínez, who in 1929 would trump her rivals by producing a male heir, Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Martínez, a boy stamped for life with the nickname Ramfis, derived from his father’s love of Verdi’s dynastic opera Aida. Through the coming years, just as he navigated with Machiavellian deliberation the political waters of the nation, so would Trujillo manipulate these women, regularly discarding a lower-class mate for a higher as a means of fashioning his image and his fate: a proper tíguere.

He proved as decisive and ruthless in public life as in private. In the next two years, he moved gradually, in the shadows, to solidify a power base from which he might seize control of the country. In 1928, the National Police was transformed by law into a proper National Army, and Trujillo was named its chief. But he had additional resources at his disposal—thuggish gangs that enforced his wishes and maintained a cordon sanitaire of plausible deniability between his official position and the more brutal imposition of his will.

He patiently bided the ineffective presidency of Horacio Vásquez, the military man whose ascent back in 1924 had convinced the North American occupiers that the country could see to itself. As Vásquez’s health failed and his government weakened toward collapse, various groups jockeyed to replace him. Each knew that it would need Trujillo on its side. None, however, fathomed the deep logic of the situation as well as he or recognized that he had fancied himself the best man to rule the country.

Presidential elections were announced for 1930, and it wasn’t clear that Vásquez was out of the running; many notables—including, at times, Trujillo, at least publicly—declared an interest in his reelection. But at the same time, Trujillo hatched an audacious, sinister plan to usurp the presidency. In broad outline, he would confide in an ally in each opposition party his intention to support its cause by staging a rebellion of disloyal troops in—where else?—the Cibao; when Vásquez sent him to quell the rebellion, for he could turn to no one else, Trujillo would instead take command of it, leading it into the capital and overseeing a rigged election that would put his candidate—whoever that might be—in power.

What Trujillo told almost no one was that he was his own preferred candidate, that he was going to pull his support from whichever side came closest to power when it would be too late to stop him, seizing the top spot for himself. He shared his plans with the American diplomats who monitored Dominican politics from a judicious remove while wielding the threat of a second occupation as a means of influencing the nation’s affairs (the Yanks were still impressed with him, if less than enthusiastic about his plan). He also shared his plans with Don Pedro Rubirosa, who declined to take part.

The scheme was so risky that Trujillo hedged against failure by keeping a small fortune in cash at the ready should it fail and he be forced to flee. As it turned out, it went almost exactly as he’d planned. He found credulous dupes in each political camp and played them sublimely: Each man, in his own ambition to usurp the presidency, was certain he had the army’s support. He fomented just the right amount of faux unrest in the Cibao; when Vásquez felt himself nervously in need of a stronger military of his own, Trujillo was promoted to minister of national defense. A little more than a week later, as the phony revolt approached the capital, Vásquez, masterfully gulled, demanded assurances of loyalty from Trujillo and, mollified, directed him to stave off the impending coup. Trujillo sent a token platoon to oppose the insurrection—with orders, of course, to join rather than stop it—and then holed himself up with a more sizable and better-armed force in the chief redoubt of Santo Domingo, the Ozama Fortress. And there he sat implacably, insisting on his loyalty to Vásquez while the besieged president was forced to resign without a shot being fired in his defense.

Trujillo allowed his coconspirators in the opposition briefly to enjoy a show of control over the nation. And he equanimously allowed the presidential election to be held, with Vásquez’s party still permitted to run a candidate. But the whole thing was a dark farce. Everyone who might have taken power had been suborned by Trujillo into treason; no one could risk exposing his own deceit by stepping forward to claim the reins. Trujillo used frank acts of intimidation and violence to curb any dissent to his own puppet candidate, Rafael Estrella Ureña, and then simply strong-armed the man out of the race. The sham election was protested even before it occurred: An oversight board resigned en masse a week before the balloting. In May 1930, Trujillo was elected president by a near unanimous (and patently fabricated) majority that would have made the most megalomaniacal despot envious; in August, amid the high pomp he had felt was due him even in his days as a telegraph operator, he was inaugurated.

With epic tenacity and iron severity, Trujillo would so impose his personality on the Dominican Republic and its people that there would be no appreciable distinction between the man and the nation. Stalin, Mao, Castro, Amin, Ceausescu, Hussein, Kim Il Sung: none would have the same degree or depth of impact on the psyche of his people. In the course of time, every home in the country would boast a sign reading “God and Trujillo”—often right out on the roof in huge letters. Santo Domingo would be renamed Ciudad Trujillo; calendars would all be dated according to the Era of Trujillo, with 1930 as Year One; Pico Duarte, at ten thousand feet the highest peak in the Caribbean, would be renamed Little Trujillo—as opposed, of course, to the big one who sat, literally, on the throne in the National Palace; the first toast at any formal dinner, especially those at which he was not in attendance, would be to the health and honor of Trujillo; and he would be spoken of not as the President or the Generalísimo or the leader but, unironically, as the Benefactor.

These ritualistic incarnations of the cult of personality didn’t emerge immediately after Trujillo took power. No, before the tíguere Trujillo could metamorphose from soldier to god, certain parties reluctant to being held in his domain would have to be made to knuckle under. In particular, there was the refined circle of bourgeois families who dominated the social and cultural life of the capital. Educated, traveled, wealthy, born to relative privilege, they looked frankly down their noses at Trujillo with his mean roots, antiquated manners, and precise mien. In 1928, still merely an ambitious officer, Trujillo had stood for election to the Club Unión, one of Santo Domingo’s most elite social institutions, and was admitted because, as everybody who observed the process knew, somebody acting under his orders had tampered with the vote. That he nevertheless went ahead and joined and attended the club was the most desperate sort of social climbing; Trujillo felt the sting of having been forced to embarrass himself and filed it away for future vindication. His revenge was swift: In 1932, after filling the club with military officers, he was elected as its president, transferred the entire membership wholesale to a newly formed premises, and had the genteel old home of the Club Unión razed.

But Trujillo characteristically had another, more cunning scheme for gaining influence over the Dominican elite. If he couldn’t enlist the parents, he would enlist the children. And he found a perfect candidate with whom to begin his campaign: the feckless, French-educated, popular son of the estimable and recently deceased Don Pedro Maria Rubirosa.

In the autumn of 1931, Porfirio was out at a drinking party with friends at the Country Club, another of Santo Domingo’s swank gathering places, when he noticed Trujillo, in full, glistening uniform, presiding over a party of military officers across the room. It was an inauspicious time for the young man: Upon his death a year earlier, Don Pedro had left his son little more than the thin veil of a good reputation—for which, truly, Porfirio had no practical use—and a deathbed wish that he continue his legal education. With the household now dominated by his brother-in-law Gilberto Sánchez Lustrino, a dreary future seemed probable. Obviously the opportunity to return to Paris was negligible, and the seemingly unavoidable legal studies would clearly tear him from the sporting, leisurely life of the streets of Santo Domingo.

Sánchez Lustrino was a true Dominican bourgeois, more dedicated to shows of courtliness and refinement than Don Pedro had ever been, a born-and-bred member of that class of gentlefolk who sneered, sometimes openly, at the pretenses of the rustic new president. And, as Porfirio didn’t care much for his brother-in-law, he was particularly pleased when an aide of Trujillo’s came to the table that night at the Country Club and told Porfirio that the president wanted to see him.

As he approached the group of soldiers who, in contrast to his boisterous friends, sipped their drinks in tightly wound decorum, Porfirio observed that “one man dominated with his energetic mien, his dark and severe gaze, a certain hidden brutality and his impeccable uniform: Trujillo.” But when he was introduced to this forbidding man, a chameleonic transformation occurred before his eyes. “I was stupefied at the change that came over him,” he later recalled. “His severe expression disappeared, and he seemed very pleased to meet the son of an old friend.”*

Porfirio knew that Trujillo had attempted to lure Don Pedro into the byzantine scheme by which he gained control of the country and that his father, partly because of his ill health, partly because he genuinely desired that his nation’s future be decided democratically, demurred. So he wasn’t entirely surprised that Trujillo made mention of his grief at Don Pedro’s passing: “You know, I was very pained by your father’s death. Men like him are what we lack today.”

Likewise, Porfirio wasn’t surprised that Trujillo failed to be impressed by his choice of profession. “Students, always with their noses in books!” he snorted. “If we don’t advance more quickly, it’s because young men like you don’t participate in this great effort.”

But there was a surprise coming: Hard on that admonition, Trujillo gently suggested that Porfirio meet him at the National Palace the next morning to discuss his future, say 10 A.M. The matter agreed, the older man stood and, begging pardon, left the club, but not without a final invitation: “Sit here with your friends. Tonight you are the guests of the President!” Porfirio waved his chums over and they joined the soldiers, who slackened their rigid posture when Trujillo left and drank brandy and champagne with the young men until the early morning hours.

He returned home and prepared for his meeting, his head heavy from the night’s indulgences. At the palace, he found Trujillo characteristically alert, erect, immaculate, and direct.

“Did you enjoy yourself last night?”

“Thanks to you, Mr. President.”

“Very good. Now let’s get to more serious matters. I am going to make you a lieutenant in my Presidential Guard.”

There was no time—or, indeed, reason—for retort. Trujillo immediately sent a lackey to fetch an administrative official, to whom he announced, “I have just named Señor Rubirosa a lieutenant. I want to see him in uniform immediately. Take him to my personal tailor, my shoemaker and my gunsmith. Tonight he’ll enter the military training academy.”

As he was outfitted in the splendor that Trujillo demanded for himself and those closest to him, Porfirio tried to wrap his mind around the situation. “At 22,” he admitted, “this was a windfall … I was sufficiently vain to believe that my personality and the name of my family had occasioned this treatment by the General.” But he managed as well to plumb Trujillo’s deeper motives. Addicted to gossip—especially as a means of dominating its subjects—Trujillo had heard about Don Pedro’s popular boy-about-town and determined to use the young man’s social standing for his own purposes. Porfirio understood it instinctively: “He had resolved to get the golden youth of the island involved in the reform of his army. I seemed a young man well suited for this plan because of the prestige of my father and the esteem that my Parisian education had among young men of my generation.”

At heart, he understood Trujillo because the two were cut of the same material: “The General was a tíguere,” he recollected, “crueler than any of the other tígueres Santo Domingo had known before. This tíguere was smarter than a fox.” In time, their relationship would evolve into a complete symbiosis. Trujillo, capable of the most ruthless acts, would pass virtually all his life in the Dominican Republic to keep his iron fist on its affairs, would commit the most ruthless acts of violence and immorality to suit his pleasure and his power, but would always take especial care to maintain at least a show of public decency. Porfirio, who would eventually emerge as his country’s most visible emissary to the outside world, habitually engaged in a more extroverted and sensational form of tíguerismo, based not on the ruthless wielding of fear but on suavity, dash, ambition, charm, and magnetism. He would provide the sophisticated public face of a brutal regime while Trujillo would, in turn, provide a steely foundation for his stupendous adventures—a mutuality that Trujillo seemed almost to have planned from the start.

It began when, hung over and greedy, Porfirio swallowed the bait dangled before him, allowing yet another of the older man’s schemes to unfold exactly as it had been planned. “Just as Trujillo imagined,” he confessed, “many young men of the Dominican upper classes followed me.”

He didn’t care if he was being used. Military life, contrary to expectations, appealed to him. As he would recall, “Physical efforts filled our days: calisthenics, various sports, arms training, target practice, horseback riding. For a young man like me, it was paradise.” It was made for him: the smart, elaborate uniforms, the camaraderie of fellow junior officers, the freedom from the responsibility to feed or house himself or define his days.

He loved his uniforms, and he looked brilliant in them: pinch-waisted, sharp-jawed, muscular, whippy, with a tight crown of wavy hair, a broad forehead, dark almond-shaped eyes, wide cheekbones, and that café au lait complexion. He wore his hair longer than other soldiers and his boots were more suited to gentlemanly pursuits than to combat or training. If the elite society of Santo Domingo wasn’t yet prepared to accept Trujillo and his military, there were certainly young ladies whose eyes, and more, would readily be caught by the spectacle of this handsome, cultured young officer. He was in his glory.

His golden impression of his new life wasn’t shared at home. His brother-in-law asserted his domain over the household by refusing to allow a soldier to live under his roof. Porfirio simply moved into the barracks.

As a young soldier, he didn’t necessarily comport himself according to the strict standards of self-control that were so important to Trujillo. Having been promoted to first lieutenant and named a member of Trujillo’s personal staff, Porfirio was required to attend all of the deadly dull affairs of protocol of which the president was so enamored. Among these was a formal ball that would be attended by all of the civilian elite of Santo Domingo, a company by whom Porfirio was loathe to be seen in the role of aide-de-camp, a mere lackey. Ordered to attend in dress whites, he showed up instead in khakis, declaring that he hadn’t been told about the day’s dress code until it was too late and that his formal uniform was in the laundry. (“I still recall the look Trujillo gave me,” he would say more than thirty years later.)

With the other junior officers, Porfirio was ordered to stay put behind Trujillo, but he boldly strode over to where a young woman he knew was seated, and he took a chair beside her to chat. A nervous senior officer approached.

“Are you Lieutenant Rubirosa?”

“Yes.”

“The President has sent me to tell you that you may dance if you wish.”

The rest of Trujillo’s military corps gaped in astonishment as Porfirio enjoyed champagne and the company of the ladies for the rest of the evening. They had reckoned he’d be lambasted; instead, he had the time of his life.

That close call with the president’s anger wasn’t quite enough to scare Porfirio into the straight and narrow that was becoming the norm for trujillistos, as the most ardent followers of the president were known. In May 1932, he injured his knee in a one-car accident in San Pedro de Macorís, thirty miles east of Santo Domingo: As if he didn’t care how he’d comported himself he’d been speeding. “The distinguished young military gentleman,” as a fawning newspaper account referred to him, was attended in a local hospital and then transported by ambulance to the capital where he was seen by top military doctors. “The injury doesn’t apparently require additional care,” the report continued. “We are happy to wish him the quickest and most complete recovery.”

His first smash-up!

In July, Trujillo told Porfirio that his presence would be required the following day at the harbor, where a full complement of officers and a military band would greet the arrival of a ship that was returning the president’s daughter, Flor de Oro, from two years of school in France. Trujillo had special need for his audacious, French-speaking aide-de-camp at this particular reunion. “She knows Paris like you do,” he explained. And then, after a pause, he added, “Well, really, not like you do, I would hope.…”

The seventeen-year-old girl who got off that boat was, as she would later remember, “bedazzled” by her reception. “ ‘El Supremo,’” as she referred to her father, “stood there in an immaculate, starched white-linen suit, flanked by shining limousines and his handpicked aides. I noticed one lieutenant instantly—handsome in a Dominican uniform that had a special flair. Even the gold buttons looked real.”

It was, of course, Porfirio. And he, of course, noticed her noticing. “She was enchanting, with dreamy eyes and hair as black as night,” he later recollected in the florid style that overcame him when he wrote of romance.

No words were exchanged between the French-educated youngsters as Trujillo whisked away the daughter with whom he’d had virtually no contact since infancy. For Flor, riding with her father was quite nearly like making a new acquaintance. From the time the North Americans came to occupy the country, Trujillo had left his first wife and their daughter behind. “We knew little of what he did,” Flor remembered. “Three or four times a year, he’d come home, each time more and more overbearing. My proud job was to wash his military belt in the river for 25 US cents.”

Aside from such childish domestic chores, the girl served another purpose for her father: Trujillo spent Flor’s childhood offering different military or political bigwigs the chance to serve as his daughter’s godfather, a singular honor in a Latin family. But he never made the designation official, continually jockeying for a better and more prestigious candidate until the girl was almost fifteen years old and had either to be baptized or to be refused admittance to the French boarding school her father had chosen for her. (To get a sense of Trujillo’s relatively low standing at the time, the lucky winner of this sweepstakes was the family doctor; Flor, for her part, suffered the mortification of being the only baptismal candidate at that particular mass who walked on her own power to the altar rather than be carried as a babe in arms.)

When Trujillo failed to gain custody of the girl upon divorcing her mother, he moved them both to a small house in Santo Domingo and enrolled the adolescent Flor in a nearby boys’ military school. But she soon found herself among the students at the Collège Féminin de Bouffémont, a short distance from Paris.

It wasn’t necessarily a comfortable fit. “Naïve, thin, with legs long as a stork’s, unable to speak French, I was the shy tropical bumpkin,” she remembered, “the classmate of girls who included a princess of Iraq.” There were luxuries: her own thoroughbred horse to replace the burro she rode back home, summer in Biarritz, winter in St. Moritz, regular trips to Paris and the opera, the theater, the museums, and the shops. Still, she felt distant from her father; for most of her life, despite documentary evidence to the contrary, she claimed never to have heard a word from him in all her years away from home.*

Having been transformed, in her own estimation, into “that exotic hybrid, a French-speaking Dominican young lady,” she returned home not sure which father she would be meeting: the one who might hand her a $100 bill and declare “buy some toys” or the one whose volcanic temper aides warned her of in advance of their meetings. “Like the humblest dominicano,” she remembered, “I prospered and suffered under his rule and came to think of him as immortal. I had succumbed to the Dominican neurosis, a willingness to swallow anything because it came from Trujillo.”

The pomp of the greeting that summer morning at the port of Santo Domingo must therefore have reassured her, along with her father’s suggestion that she plan a coming-out party for herself, a major social event in a capital that had fallen increasingly under Trujillo’s sway in all its activities. Among those Flor hoped would attend but didn’t dare invite was that dashing lieutenant; years later she confessed, “It was love at first sight.” Eager to learn more about him, she quizzed her one Dominican friend, Lina Lovatón, a tomboy athlete who had been enrolled in the Santo Domingo military school with her. Lina knew little of Porfirio, and nothing further was learned at the party, during the whole of which the aide-de-camp stood stiffly behind the president, this time in proper uniform.

Soon Trujillo announced that the family and his personal staff would pass the rest of the summer at his estate in San José de las Matas in the western foothills of the Cibao. There, the attraction between the two young people escalated, though it would not always be clear in later years how exactly or at whose instigation. Flor would forever insist that they never spoke during this period, but Porfirio would recall idle conversations in French about Parisian landmarks and “the differences between the life one encountered in Europe and in the Caribbean.” That these initial contacts were, at any rate, fleeting they would both agree.

More was, however, suspected. The childless Doña Bienvenida, jealous of Trujillo’s attentions to this daughter of his first marriage, somehow got wind of the fledgling romance—Porfirio surmised that she overheard the two speaking French in the garden one evening—and warned her husband about the lieutenant’s impertinent behavior. Without a moment’s hesitation, Porfirio was reassigned to confined duty at the fortress in San Francisco de Macorís.

Again, what happened next would be in dispute: Either she wrote him to say that she was stricken at the thought of his departure, which assumes his story that they were already on close terms; or he wrote her, out of the blue, if her account of their merely polite relations is more accurate, to express his despair at being separated from her. (Years later, Rubi explained simply, “As in any good script, we found ways of getting letters to each other.”)

Whichever, the next step was indisputably hers. Learning that she would be attending a dance in her honor in Santiago—midway, more or less, between his new post and Trujillo’s ranch—she snuck off on horseback one afternoon and phoned the fortress to invite him. He accepted and, feigning a sore throat and the need to consult a specialist in the city, made his way to Santiago on the day of the dance.

She spied him first in the town plaza, fittingly enough having his boots blacked. Then at the dance, she was seated among the town’s elite when he walked confidently over and asked her to dance. Defying every principle of decorum, they danced together repeatedly—“five times in a row,” as she recalled—and compounded the sensation by speaking in French and then, during the open-air concert following the dance, walking slowly twice around the plaza, albeit under the vigilant eye of her chaperone.

As far as Porfirio was concerned, that was it: “From that moment I was in love, and Flor was as well.”

And that was it as far as Trujillo was concerned as well.

“The dance wasn’t even over when Trujillo heard,” Flor recalled. When she returned to San José de las Matas, she was met with a storm. Her father sent her directly to her room and began grilling his aides to find out who was responsible for the communications between Porfirio and his daughter and who was responsible for letting the banished lieutenant out of the fortress to attend a dance. Flor was terrified by the degree and intensity of his temper and cowered at the door listening as he sputtered to Doña Bienvenida, “She’s gotten herself mixed up with that good-for-nothing lieutenant!”

The next day, an even more dire fate awaited Porfirio: An officer marched into his quarters and announced that he was to be immediately expelled from the army and stripped of all his gear, including, to his special pain, “my uniforms, which I loved so well.”

This was a staggering blow, and he remembered it with high drama: “I was an outcast in my own country. Ignominiously dumped and rejected by the army. Marked on the forehead with the sign of infamy which no one could ignore.” He entertained the thought of exile but he couldn’t leave the island, he said in his most lugubrious voice, because “to leave would be to lose Flor. And to lose Flor would be to die. But to stay would also be to die.”

This was no exaggeration: Trujillo was entirely capable of having his onetime protégé eliminated and, in fact, he dispatched a team of hit men that very afternoon from his goon squad, who roamed the country in ominous red Packards doing the despot’s bidding.

Had he been stationed in any other city, Porfirio might not have survived the day. But San Francisco de Macorís was, of course, his birthplace, as well as the hereditary seat of both sides of his family. “My uncles and my grandfather united in counsel,” he recalled. “My uncle Oscar gave me a well-oiled pistol. A truck was obtained. It took me to a cocoa plantation owned by one of my uncles, Pancho Ariza, about 10 kilometers away.” For more than a week, he hid in an outbuilding on the farm, “staring into space, ruminating on this cascade of catastrophes.”

He was alone in neither his anguish nor his isolation. Before bolting to his hideout, he sent off a note to Flor describing his situation. The emissary who delivered it was tied by Trujillo to a tree and thrashed, while Flor watched in horror. She locked herself away from this frightening tyrant, refusing to speak with him, refusing meals, and writing letter after unsent letter to the young man who had suddenly come to dominate her dreams. Like the heroine of a pulp novel, she would love Porfirio to spite her father.

“Flor had the same strong blood in her veins as her father,” Porfirio would recall. “A will of iron and an indomitable courage guided her. She was the only one who could stand up to her father, even if he was in a state of fury.” When Trujillo sent an intermediary to speak with her, she replied, “Tell my father that I want to marry the man I love, and I will marry him. Otherwise I would not be worthy of being his daughter.”

At least that would be how Porfirio remembered it—or maybe how he imagined it. Flor’s memory was different: a cruelly imposed isolation; the ceaseless slander of the former lieutenant by her father and stepmother; a strange limbo, like being a nonperson.

In his hideaway, Porfirio grew impatient and decided, on instinct, that danger had passed. “It has always been one of my chief principles,” he later confessed. “I will risk everything to avoid being bored.” He rode back to his uncle’s home in town, shocking his family with his sudden appearance. “You don’t have a lick of common sense,” they admonished him.

But, in fact, the worst of it seemed to have passed. Indeed, the lull emboldened Doña Ana Rubirosa to visit Trujillo to plead for her son. As Porfirio recalled it, his mother stood up to the president by asking, “What secret mark is there against our family that Señor Trujillo cannot tolerate that a Rubirosa would dare put his eyes on his daughter?”

The meeting was barely a quarter hour along when Trujillo slapped his desk and declared, “That’s enough! They will marry right away!”

This was like tripping over a winning lottery ticket on the street. From disgrace and near-death, Porfirio was now slated to marry into the first family of the country. Maybe he was in love, truly, or maybe he was too scared to cross Trujillo a second time by refusing Flor, or maybe he was as bold a tíguere as the Benefactor himself. Whichever, he had heedlessly reached for the impossible by making eyes at the president’s daughter and, through charm, gall, and luck, had seized the prize. At twenty-three, he would be wealthier and closer to power than Don Pedro ever had been.

For Flor it was a stunning shock: “Five dances in a row, two circles around a park, an innocent flirtation, and I was to marry a man I scarcely knew!”

Still, marriage would liberate her, she hoped, from a man she knew all too well; as she admitted, she was “wild to leave my prison, to run like hell from Father, an instinct that was to propel me all my life.”

The nuptials were planned for early December at the fateful ranch house where the abortive courtship transpired. Trujillo orchestrated all the details: the invitations, the ceremony, the party. The best man would be the U.S. ambassador, H. F. Arthur Schoenfeld, whom the groom had likely never met. The ceremony would be performed by the archbishop of Santo Domingo. Flor was sent to the capital to have a dress made; her fiancé stayed with his family in San Francisco de Macorís—and was named, if only for the sake of having a title worthy of his entry into the president’s family, secretary to the Dominican legation in London.

On December 2, a caravan of trucks bearing flowers and bridesmaids wended from the capital to the wedding site. The groom was flown in on a military plane. The next day, after the civil and religious ceremonies in the town, the wedding party began late, at 4:30, on what turned out to be a rainy afternoon.

In the photographs of their wedding day, the newlyweds look frightened and tiny, despite their finery and the attendant pomp. Rubi stands with shoulders thrust back and tiny waist forward, a pompadour stiff on his head and a grin set in the baby fat of his cheeks. Flor is a head shorter, with wide-set eyes and a toothy smile; she holds a hand protectively across her breast, cradling her bouquet. They might be a prom couple on their first date.

As the photo attests, the wedding wasn’t a completely comfortable experience for the groom, who hadn’t once laid eyes on his prospective father-in-law since before being sent away for flirting with Flor. “During the ceremony,” he recalled, “I saw Trujillo again for the first time. Instead of his happy air, he was cold and quiet.” Nor was the bride entirely at ease, recalling that “Father hadn’t spoken to me since my engagement.”

But it was a lavish celebration nonetheless, with music, champagne, food, dignitaries, and a trove of gifts, which the bride said “would have filled a house.” (Conspicuously absent was the bride’s mother, still shunned by Trujillo as if dead.) By 7 P.M., the newlyweds were headed to Santo Domingo in one of their presents from the Benefactor, a cream-colored, chauffeur-driven Packard with their initials embossed in real gold on the doors.

Two days later, the capital’s most prestigious newspaper, Listín Diario, carried an account of the wedding written by someone whom the editors referred to as “an esteemed and distinguished friend of ours.” The author was, in fact, Trujillo, who would employ this and other newspapers throughout the tenure of his reign to carry, pseudonymously, compositions of his own, often using them to undermine or frankly smear someone who had fallen out of his favor. He could be vicious and snide in his writings, but this time, his tone was florid and precious:

Distinguished personalities of the country added to the glow of the nuptial ceremony … beneath the cool pines of the marvelous setting of San José de las Matas, an ambiance rich in exquisiteness.… The bride, who is a flower because of her perfumed name and because of the charms that flower within her, lit up a precious wedding dress.… It was one of the most aristocratic weddings ever recorded in the social annals of the Republic. The genteel couple have united their pulsing hearts in emotion. They have our most sincere and cordial wishes for their personal journey and their eternal happiness.

According to the report, the couple would live in “a handsome chalet within the bounds of the presidential mansion in the aristocratic and comely ‘faubourg’ of Gascue” in Santo Domingo—another gift from Trujillo.

But it was to a temporary home they retired that evening, their first as husband and wife and another experience that they would remember differently.

“When we left for our honeymoon,” Porfirio remembered, “I felt like the happiest of all men.”

Flor, on the other hand, was a nervous wreck. However much she had talked with her mother, her stepmother, or her older friends, she was entirely unprepared for the night’s activities. She wore a pink negligee into the bedroom and was startled into apoplexy by the sight of her husband’s erection. “I ran all around the house, and Porfirio chased me,” she remembered.

Somehow she talked him out of consummating the marriage that night, but she couldn’t keep him at bay forever. She let him have his way, however awfully. “I didn’t like it because I bled so much, and my clothes were ruined,” she confessed. “In time, he began to make love to me in different ways, but when it was over my insides hurt a lot. He was such a handsome boy and so charming that I let him do whatever he wanted. But he took so long to ejaculate that by the end I was a little bored.”

Et voilà the maiden marital bed of a man who would become famous as one of the great lovers of his time.

* A legend would evolve that the two men met after Porfirio had captained the Dominican national polo team to a victory over Nicaragua, but Porfirio’s equestrian life only truly began after he met Trujillo, and polo wasn’t played in the Dominican Republic, certainly not at the international level, until the 1940s, when he was himself instrumental in introducing it.

* Among the surviving correspondence was a letter from Flor de Oro at Bouffémont dated October 29, 1931, in which she thanked her father for his recent telegram and declared that she was looking forward to the fulfillment of his promise to bring her home for the coming summer. He responded three weeks later with a thoughtful and tender note in which he praised her maturation and indicated that he’d heard good things about her academic progress from the headmistress of her school.