Читать книгу Titian: His Life and the Golden Age of Venice - Sheila Hale - Страница 20

ОглавлениеNINE

Sacred and Profane

Titian appears, and art takes a step in advance, and we feel that there may be some further perfection of which as yet we do not dream.

JOSEPH A. CROWE AND GIOVANNI BATTISTA CAVALCASELLE, THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TITIAN, 1881

The Assumption is a noble picture, because Titian believed in the Madonna. But he did not paint it to make any one else believe in her. He painted it, because he enjoyed rich masses of red and blue, and faces flushed with sunlight.

RUSKIN, MODERN PAINTERS, VOL. 5, 1843–60

A year or so after Titian had refused Pietro Bembo’s invitation to Rome and the Council of Ten had voted to accept his proposed battle scene for the Great Council Hall he received a private commission to paint a picture for Niccolò Aurelio, a secretary to the Council of Ten. Aurelio was the civil servant who in 1507 had signed the payment order to Giorgione for the Fondaco frescos, and it is possible that he helped Titian with the phrasing of his petition and influenced the Council’s decision in his favour. He had risen through the ranks of the ducal chancery, starting his career as an advisory notary with a salary of twenty ducats a year to his present powerful position, which paid 200 plus bonuses. The son of a professor at the University of Padua, he was an educated man and evidently good at his job, which was one of the most important in the ducal chancery. He was a close friend of Pietro Bembo, who had written him a warm letter of congratulation on his appointment and who, some think, may have devised the Neoplatonic programme for one of Titian’s most visually compelling, endlessly fascinating and enduringly popular masterpieces, now known by the much later title Sacred and Profane Love (Rome, Galleria Borghese).

Now in his early fifties, Niccolò Aurelio had fallen in love with Laura Bagarotto, a young and beautiful Paduan widow, who on the face of it could hardly have been a less suitable match. Laura’s late father, Dr Bertuccio Bagarotto, a Paduan nobleman, had been a lawyer and professor of canonical jurisprudence at the University of Padua, and a man of considerable means. But Dr Bagarotto, and some of her other blood relatives – including her maternal uncle, her cousin, her brother and her illegitimate half-brother – as well as her late husband, Francesco Borromeo, were among the members of the Paduan elite who had been singled out as traitors for supporting the short-lived imperialist occupation of their city in the summer of 1509. Within days of the recapture of Padua the family, including Laura, had been rounded up, sent under guard to Venice and thrown into prison. There was a debate in government about whether, given the status of the family, it would be more appropriate to strangle them privately in prison rather than hang them in public. Some escaped or were pardoned. But Laura’s uncle, father and husband were condemned to death, and on 1 December Dr Bagarotto was escorted from prison and hanged between the columns on the Piazzetta. He died protesting his innocence, while Laura and her mother were forced to watch his execution. Her brother, who had been spared, continued to work for the restoration of the family’s good name, and he seems eventually to have succeeded because his late father’s state pension was restored to him in 1519. Meanwhile, however, the family property, including their house in Padua near the Eremitani and Laura’s substantial dowry, was confiscated; and when in 1510 the Council of Ten decreed that the dowries of Paduan rebels be restored to their widows, Laura’s was not among them.

On the day before their marriage on 17 May 1514 Aurelio arranged for the return of her dowry. Valued at 2,100 ducats, it consisted of a white satin gown (which she had probably worn for her first marriage), twenty-five pearls and some real estate near Padua. Any increase in the value of her estate would become the property of her husband, and Aurelio did later develop the land with walled stone buildings. Although the Collegio granted approval of the marriage (another indication that there were doubts about the guilt of the family), the marriage of Laura Bagarotto and Niccolò Aurelio was the scandal of the year. Everyone talked about it, as Sanudo indicated when recording the ‘noteworthy’ event. Had Aurelio married for money? Although his job was well paid, he had no independent means, and his salary was stretched to the limit by the need to provide dowries for two sisters. He had lived with his brother in a house rented for only two ducats a year. Like so many Venetian men he had remained a bachelor, although he had fathered an illegitimate son. Had Laura married him as a means of reclaiming her dowry? Was the young Laura, who had suffered so much tragedy, attracted by the security and respectability of a middle-aged husband with an important job in government? Or was it a marriage of passion? In the three wills he made in the 1520s Aurelio refers to Laura as his most dear, beloved and cherished consort, whom he cannot imagine wanting to remarry after his death. He also expresses tenderness for the entire family, especially their daughter Giulietta, as well as for his natural son Marco and for Francesco, the natural son of his deceased brother Antonio, both of whom Laura had helped to bring up.

In August 1523, nearly a decade after their marriage, Aurelio was elected grand chancellor by the Great Council. It was the top job in the Venetian bureaucracy, carried a salary of 300 ducats per year plus bonuses, and made Aurelio the most powerful man in government after the doge and the procurators. He beat five other candidates – one of whom, Gasparo di la Vedoa, was the doge’s favourite. Sanudo described Vedoa’s black face when he heard he had failed to carry the election, and such was his distress that he died the next year. Aurelio’s victory enraged a cabal of the losers, and less than a year later his enemies trumped up charges that he had accepted bribes to allow some criminals to escape justice. On 15 June 1524, after attending a banquet with Laura, rumours reached him of a plot. In July he was arrested, tortured on the rack and banished to Treviso for life. But a year later, possibly thanks to an intervention by Bembo, he was permitted to go to Padua, where he was reunited with Laura, who soon bore him a son, Antonio. But Niccolò Aurelio was a broken man. He died on 17 June 1531. Sanudo tells us that Laura honoured his wish to be buried in San Giorgio Maggiore and that it poured with rain on the day of his funeral. She never remarried.1

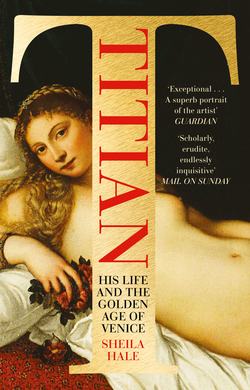

Titian immortalized the love story of Laura Bagarotto and Niccolò Aurelio with a painting that is one of the icons of Italian Renaissance art.2 The earliest references to it are relatively straightforward. In the years after its arrival in the Villa Borghese in the seventeenth century, it was called ‘Beauty Adorned and Unadorned’ and ‘Divine Love and Profane Love, with Cupid fishing in a basin’. Ridolfi described it as ‘two ladies near a spring in which a child is looking at itself’. The title Sacred and Profane was attached to the painting in the eighteenth century. But it was not until the end of nineteenth century that art historians educated in the classics began their attempts to possess by explanation this last and greatest of Titian’s Giorgionesque secular paintings with more and less arcane theories about its meaning and the classical or Renaissance stories it might illustrate.3 Although few have doubted that the naked woman in the painting is Venus, some have seen the two women as representing her double role as goddess of both chastity and carnal love. Some, taking their cue from the eighteenth-century title of the painting, have seen the naked Venus as ‘sacred’ in the sense that she is the celestial goddess of unadorned truth and the higher love, while her clothed counterpart is an earth-bound mortal and therefore ‘profane’.

A more recent and more plausible interpretation4 inverts that theory. Venus may have been the most beautiful of goddesses, but she was notorious for sleeping around and was for that reason the goddess of whores as well as of brides. According to the Neoplatonic theory of love then being propagated by Bembo and Castiglione, carnal love, as encouraged by Venus and her son Cupid, leads step by step to the ideal love in which raging passion, harnessed by the human intellect and capacity for discipline, ascends to the perfect love of God and to Christian marriage in which the purpose of sexual relations is to produce children. It is the clothed bride in Titian’s painting who represents that ideal of what has been called a ‘baptized eros’.5 If this is indeed the meaning of Titian’s painting it could have been suggested by Pietro Bembo’s famous and widely read Gli Asolani, in which a party of young friends discuss the nature of profane and sacred love. Bembo was, as it happened, in Venice at the time of the marriage, travelling on a diplomatic mission, and he would certainly have given a wedding present to his friend Niccolò Aurelio. Poems in praise of marriage were traditional wedding gifts. Bembo, who was also acquainted with Titian, and was not lacking in imagination or appreciation for the art of painting, might have decided instead on a painted poem. If so, we have the greatest Venetian poet of his day to thank for the most sublime Venetian painting about love and marriage.6

The link with Niccolò Aurelio was not rediscovered until the early twentieth century when Sanudo’s diaries were first published7 and a scholar matched the escutcheon on the front of the fountain to an engraving of the Aurelio family coat of arms. More recently, thanks to the interest of academic historians in the material culture of the Renaissance, scholars have noticed what would have been immediately obvious to any sixteenth-century Venetian who saw the painting in the Aurelio household. Sacred and Profane Love is an epithalamium, a poem about a marriage, in the same tradition as Botticelli’s Primavera.8 Venetian brides did not necessarily wear white. Their wedding dresses could be any colour, the main requirement being that they were made of expensive materials and worn with ornate jewellery.9 Titian originally dressed his bride in the red that can still be detected beneath the white he painted over it. She wears the belt, or ceston, that refers to the girdle of Venus, which had the power to bestow sexual attraction on its wearer, but was also a sign of the bride’s chastity; it would have been sent by her betrothed as a tribute of love and a token of marital fidelity. The ceston, like the crown of myrtle in her hair, had been associated with sex and marriage since antiquity. Her hands are protected by gloves, which will be removed just before the ring is slipped on her naked finger. The pot she holds in her gloved left hand was a traditional wedding gift from the husband, associated with childbirth. The fluted silver bowl, the bride’s gift to the groom, would be inscribed with her coat of arms.10 It might be used for sweetmeats, for washing her hands after childbirth or for the baptism of the baby. The fictive relief carving on the sarcophagus of an unharnessed horse was a familiar symbol of unbridled passion – horse, cavallo, was a euphemism for phallus, fallo – which would be tamed by marriage just as the flames of the smoking torch held by Venus have been doused.

Cupid stirs the water in the sarcophagus, which is transformed by the power of love into a life-giving fountain. The water falls through a brass spigot on to the rose bush, the rose being a flower sacred to Cupid’s mother because she pricked her foot on a rose thorn and her blood stained some of the white roses red.11 Rabbits, little symbols of fecundity, race across the beautiful landscape lit by the slanting rays of the evening sun, where a couple embracing in the far distance are pursued by huntsmen chasing after love. Even the lake calls to mind the lake in Venus’ garden at Paphos. The bride, however, seems to be unaware of where she is or of the presence of the goddess who gazes at her encouragingly but must remain invisible to a mortal.

The two women are linked by the similarity of their features – a typical compliment to a bride who in the eyes of her husband is as beautiful as Venus; and by one of Titian’s simplest and most effective chromatic schemes: blood red, the colour of passion, for Venus’ cloak and the bride’s sleeves; the chaste white of her wedding dress echoed by the veil that covers the mons veneris of the goddess. We know from a cleaning and relining completed in 199512 that Titian did not decide on the final colours and composition without his usual trial and error and that he used a canvas on which he seems to have begun a painting of a different subject. He began with the sarcophagus and a naked standing figure in profile on the right. Originally he placed the two girls closer together. There was another large figure behind Cupid. The underdrawings revealed when the old lining was removed are thick and look as though they were rapidly executed with the help of his fingertips. It seems that he worked on the design at speed, propelled perhaps by a rush of inspiration or a deadline. If so, the freshness and originality of the finished masterpiece may owe something to the pressure to complete it on time.

Giovanni Bellini died on the morning of 29 November 1516. He had chosen to be buried in a modest second-hand tomb near the graves of his wife’s family and his brother Gentile in a cemetery attached to the Dominican preaching church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo,13 where he had worshipped and where his funeral was held. ‘His fame is known throughout the world, and old as he was he continued to paint excellently,’ wrote Sanudo (who unfortunately left a blank space for Giovanni’s exact age). Titian, who had not yet delivered the battle scene for the Great Council Hall, may not have received the sanseria he had hoped to be awarded on Giovanni’s death.14 He was, however, immediately commissioned to complete the canvas for the Great Council Hall of the Humiliation of the Emperor Barbarossa, which Giovanni had left unfinished. But more compelling commissions were piling up.

At the time of Giovanni Bellini’s death Titian was also at work across the city in the Franciscan Frari, the other great mendicant church of Venice, on a painting in which Christ’s Apostles express their astonishment, joy and thanksgiving as they witness the miraculous Assumption of His Mother into Heaven. Known as Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari to distinguish it from the many other Venetian churches dedicated to the Virgin, the Frari was and is the largest and most beautiful Gothic church in the city, with the second tallest bell tower after that of San Marco. The arch of its magnificent fifteenth-century monks’ choir, the only one that survives in Venice and one of the few in Italy still in situ, frames the view from the nave of the high altar. Titian had been invited by the energetic new guardian of the church, Brother Germano da Casale, to paint an Assumption of the Virgin for this prominent position, where it would be seen by congregations composed of every class from the poorest Venetians to visiting dignitaries and the richest and most powerful nobles. Titian must have played a part in the design of the frame, apparently completed in 1516, which determined the dimensions of his enormous painting: seven metres high and three and a half wide, making it the largest altarpiece ever attempted in Venice and the focal point of the Frari, where it dominates the view, framed a second time by the arch of the monks’ choir, from the far end of the nave. But size was only one of the challenges Titian would have to meet. His painting would have to be accessible to illiterate worshippers in the congregations of a preaching church. It would have to work against the counter-light streaming through the south-facing lancet windows of the apse. And it would require the ability to organize a team of carpenters to build the support and of assistants to help Titian execute his ideas as the painting progressed.

He decided on panel as a more stable support than canvas, and with his inherited understanding of wood must have enjoyed supervising the carpentry. Twenty-one cedar panels, each three centimetres thick, are held together by sixty walnut pegs and larch struts supported by batons nailed to the back of the support. The nails penetrated the surface of the panel and were renailed backwards at Titian’s request.15 A studio in the convent was set up for him and his team of assistants, where a hundred or more curious friars observed their progress and plagued Titian with their comments before finally recognizing, so Ridolfi tells us, that ‘painting was not a profession for them and that knowing their breviaries was very much different from understanding the art of painting’.

The germ of the composition seems to have been one or more of several chalk drawings by Fra Bartolommeo of flying, twisting virgins, which Titian could have seen on the Tuscan artist’s visit to Venice in 1508. The arrangement of the Apostles seems to have been suggested by Mantegna’s fresco of the Assumption in the Paduan church of the Eremitani. But Titian’s Assunta (as it is usually called) turned out to be entirely unlike any work of art ever seen in Venice or anywhere else, a masterpiece that would unsettle some of his contemporaries and change the direction of European art in a way that was not repeated until Picasso reinvented the art of painting four centuries later. We see it through the veil of its powerful influence on Counter-Reformation and Rococo painting. But to appreciate the impact it made at the time one need only take a boat to the island of Murano, where Giovanni Bellini’s static and stately version of a similar subject, painted less than a decade earlier, can still be seen in the Franciscan church of San Pietro Martire. Bellini’s Virgin stands quietly praying on a cloud-shaped pedestal raised just above the landscape and behind the fathers of the Church, who stand in a semicircle meditating silently on the vision.

Titian’s Virgin by contrast is propelled upward to heaven as though by her own spiralling momentum and is surrounded by a swarm of cavorting baby angels, while the miraculous ascent is witnessed by a crowd of amazed, larger-than-life-size Apostles, all in movement. Her robe and cloak billow about her supple body; her face and raised arms express terror and exaltation as she approaches God the Father, Who has burst through what appears to be the black unknown into the halo of celestial light that encircles her still youthful face. According to Franciscan tradition, which had been sanctified as doctrine by the Franciscan pope Sixtus V in 1496 – but was heatedly contested by Dominicans for centuries to come – the Virgin, like her Son, had been immaculately conceived. Uncorrupted by original sin, she was therefore not subject to decay and death but was physically assumed into heaven as a young and beautiful woman. Since the question of how she had been transported had never been settled, it was left to artists to depict her Assumption as they or their patrons envisaged it.16

One of Titian’s most original decisions was to eschew the traditional landscape background. His Assumption takes place, not in the countryside or in a fictive architectural space, but as though in the church itself. His awestruck, gesticulating Apostles, cast in shadow by the silhouette of the ascending Virgin, could have been members of a real congregation. They react to the supernatural event in a two-dimensional space ‘as natural as nature’17 and as solid as a building that seems to extend the apse beyond its windows. The sharp reds of the robes that mark the base angles and apex of the pyramidal composition flash against the warmer brick and terracotta of the choir and floor of the church. The swag of stormy clouds and rejoicing angels repeats in reverse the arch of the choir screen, thus completing a second full circle around the circle of golden light that out-dazzles the daylight that streams through the apse windows. There cannot be many other works of art that combine such architectonic solidity with such dynamism, or which are in such perfect harmony with the buildings for which they were created.

Dolce, writing nearly forty years after the unveiling of the Assunta, was the first to praise it in print:

It seems that she really ascends, with a face full of humility, and her draperies fly lightly. On the ground are the Apostles, who by their diverse attitudes demonstrate joy and amazement, and they are for the most part larger than life. In the panel are combined the sublime grandeur of Michelangelo, the charm and grace of Raphael, and the true colours of Nature.

But in his eagerness to promote and doubtless to please Titian, Dolce gilded the lily, asserting that Titian had painted the Assunta before Giorgione had produced any oil paintings, which would put it a decade earlier than the date that was clearly visible on the frame. He was doubtless right, however, that ‘clumsy painters and the ignorant crowd, accustomed to the cold, dead works of the Bellini brothers and Alvise Vivarini, which were without movement and relief, spoke very ill of the finished work’. Ridolfi repeated an old story, that the friars including even the enlightened Fra Germano objected to the excessively large figures of the Apostles, ‘thereby causing the artist to endure making no small effort to correct their lack of understanding and to help them comprehend why the figures had to be in proportion to the extremely large location in which they were to be seen, as well as to discuss whether it would be advantageous to make them smaller’. (Ridolfi also claimed that the friars came to value the painting only after the emperor’s ambassador tried to buy it for an enormous sum. But about this he must have been mistaken, because the emperor’s ambassador was not in Venice at the time.)

By the time Vasari saw the Assunta it was so obscured by an accumulation of dust and candle grease that he guessed it was on canvas and merely reported that it had not been looked after very well and was too dark to make out. When Sir Joshua Reynolds visited the Frari in 1752, he found it ‘most terribly dark but nobly painted’. It remained shrouded in grime and difficult to see against the light of the lancet windows until in 1817, during the Austrian occupation of Venice, the Assunta was removed from its frame and taken to the newly opened Accademia Gallery where it remained until after the First World War. It was displayed, along with other sixteenth-century paintings brought in from religious foundations and palaces in Venice and the Veneto, in the chapter room of the former Scuola della Carità (the first room at the top of the stairs, now hung with Venetian Primitives), where the ceiling was raised above it to accommodate its height.18 The sculptor Antonio Canova, who formally opened the room to the public in 1822, described Titian’s Assunta as the greatest painting in the world. The gallery was thronged. Artists queued up to copy it, writers to describe it. Some imagined they could hear its music.19

Now cleaned and well lit, Titian’s Assunta is no longer a pilgrimage piece. As happens to all successfully original works of art, its impact has to some extent been diluted by its influence. Titian would be dismayed to know that the more popular painting in the Frari is Giovanni Bellini’s neo-Byzantine Sacred Conversation in the sacristy. But if you stand for a while, perhaps on a winter’s afternoon when you might have the church all to yourself, and watch Titian’s Virgin flying up to heaven beyond the apse, you will notice a detail that sometimes escapes attention: one of the angels flanking God the Father holds a crown. It is with this that He will crown the Virgin, the protector of Venice, as Queen of Heaven, just as He had made Venice, at the end of the long wars of Cambrai, once again queen of cities. It was a time for Allelujas. And if you listen to the painting you may hear a chorus singing in the monks’ choir, accompanied perhaps by both church organs.

The unveiling took place on 19 May 1518. It was San Bernardino’s day, a public holiday, chosen to allow members of the government to attend. We know the date from Sanudo, whose maddeningly laconic diary entry however tells us nothing more than what we can see from Titian’s signature, ‘Ticianus’, and the inscription on the frame that records Brother Germano’s inspired patronage: ‘In 1516 Fra Germano arranged for the building of his altar to the Virgin Mother of the Eternal Creator assumed into Heaven.’ But Sanudo’s presence at the ceremony indicates that it was an important social event, attended by foreign dignitaries and members of government in their black togas or the brightly coloured robes and stoles worn by those who held high office. The papal legate to Venice, Altobello Averoldi, was evidently impressed: five months later he ordered an altarpiece from Titian for a church in his native city, Brescia. The following year Titian’s first private patron Jacopo Pesaro, to whom Fra Germano had recently conceded patronage rights to an altar in the left nave of the Frari, commissioned Titian to paint the altarpiece for it. Even before the formal unveiling, enthusiastic descriptions of the Assunta in progress may have reached the ears of Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, a keen patron of contemporary artists who had, however, so far failed to recognize Titian as a painter of the first order.

Titian had worked for the duke in 1516, when he lodged with two assistants in the ducal castle from 22 February until the end of March. (The ducal account book of expenditure for that period records that the party was provided with salad, salted meat, oil, chestnuts, oranges, tallow candles, cheese and five measures of wine.) The visit may have had a diplomatic purpose. As the war of Cambrai drew to a close, the Duchy of Ferrara had been linked to its former enemy Venice by the Franco-Venetian treaty negotiated at Blois in the spring of 1513. After the decisive battle at Marignano in 1515, the pope, Leo X, had no choice but to side with the victorious Francis I, who had taken Alfonso under his wing and was conducting exploratory negotiations about the possibility of restoring Reggio and Modena to Ferrara.

Alfonso, who owed allegiance to both pope and emperor but who had more reason to fear the territorial ambitions of the pope, had minted gold coins the reverses of which were inscribed in Latin with the concluding words of the episode told in the three Synoptic Gospels about a Pharisee who, trying to trick Christ, asked: ‘Is it lawful for us to give tribute unto Caesar, or no?’ And Christ replied: ‘Show me a penny. Whose image and superscription hath it? They answered, and said Caesar’s. And He said unto them, Render therefore unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God the things which be God’s.’20 This was the story the duke chose for Titian to paint on the door of a cabinet in which he kept his minted coins and collection of antique Roman coins and medals. It was a very rare subject. Titian’s Tribute Money (Dresden, Gemäldegalerie), indeed, was the earliest Italian rendering of it, and he pulled out all the stops to produce a picture that would allude to the antiquarian interests of the Este dynasty and give an added dimension to the precious contents of the cabinet.

The Tribute Money is Titian’s sleekest, most polished early work. Ridolfi claimed that when the emperor Charles V’s envoy to Ferrara saw it several years later he expressed his surprise that anyone could compete so successfully with Dürer. Vasari – who may have been recording Titian’s opinion rather than his own – described the head of Christ as ‘stupendous and miraculous’, and wrote that all artists who saw it considered it the most perfect painting Titian had ever produced. Although court painters did not normally sign pictures, this was the first of several works for the Duke of Ferrara that Titian, perhaps to emphasize that he was not a court painter, signed ‘TICIANUS F’. He placed his signature on the collar of the Pharisee; and if, as has been suggested,21 this malign figure is a self-portrait, the joke seems remarkably intimate coming from a young painter working for his first foreign prince.

In 1517 Titian received another diplomatic commission from the Venetian government. It was a painting, now lost, of St George, St Michael and St Theodore, which was sent as an official gift to Odet de Foix, the Seigneur de Lautrec, who had commanded the French army at Marignano and was now governor of Milan. Titian was also doing small jobs for Alfonso d’Este, who in August of that year paid him forty-eight lire for a sketch of a bronze horse. Early in the following winter Alfonso, who was planning to rebuild part of his castle, asked Titian to send him a sketch of a Venetian balcony and to supply him with a painting for the ducal bathroom of nymphs bathing. Titian responded to these requests with a letter – it is not in his own handwriting – saying that if his sketches of the balcony were not satisfactory he would do others because he was dedicated, breath, body and soul, to serving His Excellency, and he was honoured to obey him whenever and in whatever way he commanded. As for the Bathing Scene, he had not forgotten it, indeed he was working on it daily and the duke need only let him know when he would like it sent.

But a few weeks later Alfonso was persuaded by reports of the Assunta to cancel the Bathing Scene and to offer Titian a much more ambitious commission. On 1 April 1518, in a letter addressed to ‘the Most Illustrious and Excellent Lord, my Lord Duke of Ferrara’ and written by the same hand as the earlier letter about the balcony, Titian acknowledged receipt of a canvas, stretcher and instructions for a painting. Titian’s intellectually sophisticated ghost wrote that he found the subject so beautiful and ingenious that the more he thought about it the more he became convinced that the grandeur of the art of the antique painters was due to the generosity of great princes, who had allowed painters to take the credit for works of art which merely gave shape to the ingenuity and spirit of those who had commissioned them. To say that the soul of a work of art resided in its patron while the artist was merely the physical agent was an extraordinary conceit and certainly not one that would have occurred to any painter, let alone one as proud of his powers of invention as Titian. (Giovanni Bellini had refused outright to paint a subject according to a programme described to him by Isabella d’Este.) So whoever composed that letter must have been a friend whose judgement Titian trusted absolutely. Although there is no way of proving the identity of the author of the letter, the most likely candidate is Andrea Navagero, the poet and classical scholar who had persuaded Titian to refuse Bembo’s invitation to Rome in 1513 and who had himself recently returned from Rome to Venice.22

On 22 April Jacopo Tebaldi, the Ferrarese ambassador in Venice, reported to the duke that he had paid a visit to Titian. He had given him the ‘the sketch of that little figure’ and Titian had taken note of the duke’s further instructions for his painting. Titian wanted to know exactly where the duke proposed to hang it in relation to the other pictures in the room,23 and he promised to begin work on it that very morning. There is no record of Alfonso’s reply. Perhaps he took the opportunity to answer Titian’s question about where the picture would hang, and to see the Assunta with his own eyes when he paid a visit to Venice in early June. We can be sure that the duke nagged the painter in person – the sight of Titian’s astonishing painting of the Virgin flying up to heaven surrounded by angels can only have inflamed his natural impatience – and that Titian disarmed him with his usual courteous but disingenuous assurances that he would make the painting a priority.

If Titian hoped that the government would continue to excuse his failure to make progress with the battle scene while he satisfied the demands of the Duke of Ferrara, he was mistaken. On 3 July 1518 he received a stern warning from the Salt Office. Unless he began immediately on the canvas for the Great Council Hall, which had been neglected for so many years, and unless he continued to work on it until it was finished, their magnificences would have it painted by another artist at Titian’s expense. Titian, who had reason to be confident that there was no other artist capable of or even willing to attempt a painting for the difficult site between the windows facing on to the Grand Canal, seems to have deflected the threat by agreeing to complete Giovanni Bellini’s unfinished Submission of Barbarossa,24 which he did not actually get around to for another four years. His private practice was busier than ever before. His mind was racing with fresher and more compelling ideas. Titian would not be rushed, either by his own government or by the Duke of Ferrara.

He did not complete Alfonso d’Este’s painting until January 1520, twenty months after he had promised to begin it ‘that very morning’. It would be the first of three canvases for the duke with which the artist who had transformed Christian art with his Ascending Virgin surrounded by angels breathed new life into painted fables about the orgiastic revels of pagan gods and goddesses and their freedom to behave in ways that mortal men could only relive in their classically inspired imaginations. For the Worship of Venus (Madrid, Prado) he borrowed his own baby angels from the Assunta and let them loose in an apple orchard where he turned them into a swarm of unruly little pagan cupids tumbling and flying about, gathering and throwing apples, shooting arrows, wrestling, hugging, kissing and dancing before a statue of Venus, the goddess of uninhibited sexual love.25

Titian’s life was about to take a new turn, one that would lead him to international fame and place Venice on the map as an artistic centre to rival the glory days of Florence and Rome. He had never lacked confidence, but now, as he entered his thirties, he knew this about himself: he was more than ready to work for the greatest princely collectors, but he would do so at his own pace; and if he was required to spend time at their glittering courts, he would never stay long enough to be anyone’s court painter, always returning as soon as possible to Republican Venice.