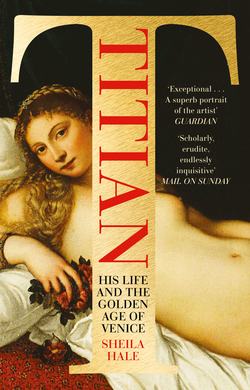

Читать книгу Titian: His Life and the Golden Age of Venice - Sheila Hale - Страница 23

ОглавлениеTWO

Bacchus and Ariadne

… Mad for you, Ariadne, flushed with love …

And, all around, the maenads pranced in frenzy …

Tossing their heads; some of them brandishing

The sacred vine-wreathed rod, some bandying

Gobbets of mangled bullock, others twining

Their waists with belts of writhing snakes …

CATULLUS, CARMINA, FIRST CENTURY BC1

He who wraps the vision in lights and shadows, in iridescent or glowing colour, until form be half lost in pattern, may, as did Titian in his ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’, create a talisman as powerfully charged with intellectual virtue as though it were a jewel-studded door of the city seen on Patmos.

W. B. YEATS, CITED BY RONALD SCHUCHARD, ‘YEATS, TITIAN AND THE NEW FRENCH PAINTING’, 1989

As Alfonso d’Este’s ambassador in Venice, Jacopo Tebaldi was required to spend much of his time shadowing Titian. When Titian was away Tebaldi made it his business to discover where, why and for how long. When Titian was in Venice he haunted his studio. He brought messages from the duke, and sent back up-to-the-minute reports of Titian’s replies, questions, moods and current state of health. The more Titian procrastinated, the more obsessively the duke pursued the painter he now recognized as an unequalled master, and the more Tebaldi had to use his diplomatic skills to see through Titian’s excuses and think up ways of persuading him to deliver the paintings he had promised the duke. Tebaldi was no more interested in art than most ambassadors then or now, but he was a good detective. Not all of his correspondence with the duke survives, but enough remains to allow us, too, to follow Titian, sometimes week by week, over the next years; and to understand the forceful, self-assured, shrewd and charismatic personality of an artist born in a small house in the mountains who from then on would be pursued by the powerful rulers of his day.2 Although we know nothing for certain about his physical appearance before the self-portraits painted when he was in his middle and late years, we can deduce from his relationship with the Duke of Ferrara that this was a man who knew his worth as an artist perhaps even more than he genuinely respected his social superiors.

In January 1520, after eighty-six days in Ferrara finishing the Worship of Venus, Titian returned to Venice. No sooner was he home again than Alfonso began making further demands on his time through Tebaldi. Titian’s studio was crowded with works in progress. He was working concurrently on the altarpieces for Brescia, Ancona, the Frari and probably Treviso, as well as a number of portraits,3 and, so the duke hoped, his Bacchus and Ariadne. But when Alfonso requested him to put down his brushes and arrange for a set of glasses to be made in Murano for the ducal table, Titian ordered the glasses and fixed on a price. The duke wished to know if the furnaces on Murano were capable of producing as well as glass the brightly painted tin-glazed pottery known as majolica ware. By 28 January Titian had prepared the design of a trial vase, which was successfully fired and shown to Tebaldi. On 5 and 11 February Titian and Tebaldi went to Murano where they drew up a contract for twelve vases to be delivered within eight days along with the glasses. The production of majolica had ceased in Ferrara during the Cambrai war, and Alfonso, determined to revive a craft that was particularly dear to his heart, turned to Titian for help. Titian found a master potter and sent him to Ferrara. Then it seemed that there was no artisan in Ferrara who could be trusted with gilding the frame of the Worship of Venus. Titian persuaded an old, experienced master gilder he knew in Venice to go to Ferrara and gild the frame as well as the majolica jars in which the duke’s spices were to be stored. So far Titian had accepted such distractions with good humour. He did not, however, conceal his irritation when he heard that an incompetent person had applied to his Worship of Venus a coat of varnish that had obscured and in places damaged its surface. He agreed to come to Ferrara to restore the painting, but there is no evidence that he did so.

Meanwhile, it reached the ear of the duke that a curiosity and talking point in Venice was an exotic animal imported by Giovanni Cornaro who kept it in his beautiful palace on the Grand Canal at San Maurizio. Alfonso wrote to his ambassador on 29 May:

Messer Jacomo. Take care to speak immediately to Titian and tell him to do me a portrait as soon as possible and as though it were alive of an animal called gazelle, which is in the house of the most honourable Giovanni Cornaro. It should fill the entire canvas. Attend to this matter diligently and then send it to us immediately advising us of the cost. And remember to send those spice jars, which were supposed to be sent to us some days ago.

Tebaldi and Titian hastened to Palazzo Cornaro only to learn that the gazelle was dead and its body had been thrown in the canal. They were however shown a painting by Giovanni Bellini in which he had incorporated a portrait of the gazelle, and on 1 June Titian offered to make a copy of it for the duke. If Alfonso accepted the suggestion Titian’s gazelle has disappeared, and the Bellini painting, of which there is no record, was presumably lost in the spectacular fire that destroyed the Cornaro palace in 1532.4

Although Titian was compliant enough to run such errands for the duke, the summer passed with no sign of the paintings he had agreed to provide before leaving Ferrara. Alfonso lost patience. On 17 November he wrote to Tebaldi:

Messer Jacomo. See to it that you speak to Titian, and tell him from us that when he left Ferrara he promised us many things, and up to now we have not seen that he has kept any of them, and among others he promised to do for us that canvas which we especially expect from him [the Bacchus and Ariadne]: and because it does not seem to us worthy of him that he should fail to keep his promises, urge him to behave in a way that will not give us cause to be saddened and angered with him, and to make sure above all that we have the above-mentioned canvas quickly.

Titian replied through Tebaldi that he had not received the canvas and stretcher or the measurements for the Bacchus and Ariadne and had therefore assumed that the duke no longer wanted it, but that once he had the necessary materials and information he would finish it by the next Ascension Day, which would fall in May.

Tebaldi knew perfectly well that Titian was playing for time while working instead on the papal legate’s altarpiece for Brescia. It was common knowledge that he had finished one of the panels, a depiction of St Sebastian that was the talk of Venice. Tebaldi, who was not a high-ranking diplomat for nothing, wisely made a joke of it, telling Titian that his delaying tactics were every bit as clever as his paintings but that he might as well confess that having tasted priests’ money he had lost interest in working for a mere duke. Titian replied that on the contrary he would do anything to please the duke; he would go so far as to make forged money for him. He would never leave the service of the duke, neither for priests nor for friars. He would stand day and night with paintbrush in hand to serve him. But, yes, it was true that he had worked very hard on the St Sebastian, which is in fact one of the few figures for which detailed preparatory drawings, in pen and brush, survive (Frankfurt am Main, Städelsches Kunstinstitut). He considered it to be the finest thing he had done up to that time, and itself worth every soldo of the 200 ducats he had been offered for the entire altarpiece.

Tebaldi decided that that he’d best see this great work for himself. In Titian’s studio he found himself among a crowd of admirers gazing at a painting of a muscular, twisting figure that was unprecedented in Venetian art, and which later became one of Titian’s most celebrated and copied paintings. He had used as his model a side view of the famous Hellenistic sculpture of Laocoön, of which he would have had a reduced plaster copy in his studio, and may also have seen a sketch of Michelangelo’s powerful Rebellious Slave, which had itself been inspired by the Laocoön. Whereas Florentine painters had achieved anatomical accuracy through dissections of human bodies and study of classical models, Titian, using only sketches and reduced models, had rivalled the greatest antique and contemporary sculpture in paint without seeing the originals in Rome. It was also moderately daring at a time when it was beginning to be considered indecorous to use pagan models for Christian subjects.5 Tebaldi sent the duke the following description:

The body is tied to a column6 with one arm high up, the other low down. The whole figure writhes in such a way as to display almost all of the back. In all parts there is evidence of suffering, and all from one arrow that sticks in the middle of the body. I am no judge, because I do not understand drawing, but looking at the limbs and muscles the figure seems to me to be as natural as a corpse.

On 1 December Tebaldi reported to the duke that he had told Titian that he was throwing it away by giving it to a priest who would only take it off to Brescia. Privately Titian may have agreed. Averoldi had ordered a triptych, a format that had gone out of fashion in sophisticated artistic centres and was wasted on Titian, whose genius was for integrated composition. Nevertheless, when Tebaldi made the shocking, but perhaps not entirely unexpected, proposal that Titian should sell the St Sebastian to Alfonso and secretly replace it with a copy for Averoldi, Titian pretended to hesitate. The duke was excited by the thought of possessing a painting that had attracted so much admiration; and on 20 December, after further circuitous conversations with Titian, Tebaldi was able to convey the news that Titian had agreed to the scam, saying, ‘The Duke may demand my poor life of me, and although I would not carry out this swindle [truffa] against the Papal Legate for any man in the world, I would gladly do so for His Excellency if he were to pay me 60 ducats for the St Sebastian.’ Sixty ducats, he couldn’t resist adding, was a bargain considering that the Averoldi altarpiece, for which, as he had previously had occasion to mention, he was to receive 200 ducats, would consist of three figures and the St Sebastian was worth all of them.

Three days later Alfonso came to his senses. He had had more than enough experience of the consequences of offending the papacy and realized that the risk of aggravating Pope Leo, whose sights were set on attaching Ferrara and its hinterland to the Papal States, by swindling his legate in Venice was simply too great. He ordered Tebaldi to convey to Titian that he had changed his mind about cheating the legate:

having thought about that matter of the St Sebastian we have resolved not do this injury to The Most Reverend Legate; and that he, Titian, should think of serving us well with that work which he is supposed to do for us which now weighs more heavily on our mind than anything else, and remind him about that Head7 which he began for us before leaving Ferrara.

The letter was preceded by the delivery to Titian of the canvas for Bacchus and Ariadne and a sweetener of twenty-five scudi.

A few months later it must have occurred to Alfonso that for all the good his sudden rush of common sense had done he might as well have gone along with the St Sebastian swindle. By the summer of 1521 Leo X, having enthusiastically formed an alliance with the twenty-one-year-old Habsburg emperor Charles V, was as committed to driving Alfonso’s French allies out of Italy as Julius II had been. Leo excommunicated Alfonso and imposed an interdict on Ferrara, and while the French and Venetians dragged their heels, his troops attacked and occupied key territories and towns of the dukedom of Ferrara. Even with the cards so heavily stacked against him, Alfonso refused to surrender or disarm. He was saved only at the last minute by an event that could not have been predicted. Leo, who was only forty-six, was found dead in bed on the morning of 1 December. He was overweight, drank too much and had been in poor health for some time, but his death was so sudden that poison was suspected, although it seems more likely that he had contracted malaria on a hunting expedition along the Tiber. He had left the papacy all but bankrupt. But what mattered to Alfonso at the time was that Leo’s death gave him the opportunity to recapture most of his hinterland, including Reggio and Modena. He celebrated with a minting of silver coins on which a shepherd rescues a lamb from the jaws of a lion with the biblical inscription de manu leonis.

Alfonso was less fortunate in his negotiations with Titian, whose work on the Bacchus and Ariadne had been delayed by yet another distraction. This time it was an enormous fresco commissioned in the summer of 1521 by the local government of Vicenza for the loggia of their communal palace. The subject was the Judgement of Solomon, an obvious reference to the administration of justice. It was over six metres wide, more than twice the size of his Miracle of the Speaking Child in Padua, which probably explains the substantial fee of 100 ducats plus six more for painting the vaults of the loggia, and another ten for expenses and three helpers: his brother Francesco, who worked alongside him for thirty days, a certain Gregorio and a Bartolomeo, a ‘master painter’. Nothing more is known about Gregorio and Bartolomeo, who may have been local painters taken on for this job only. Paris Bordone, possibly Titian’s former studio assistant, was working on a much smaller Drunkenness of Noah (for which he was paid twenty-one ducats) adjacent to Titian’s fresco.8 If he was still smarting from Titian’s treatment of him several years earlier (in connection with the San Nicolò ai Frari altarpiece) he was never able to throw off the master’s influence. It was said that when a group of government officials came to survey the completed decorations of the loggia they praised Bordone’s fresco as the equal of Titian’s. If the story is true it may have reminded Titian of the occasion, more than a decade earlier, when Giorgione had been congratulated for painting Titian’s façade of the German exchange house, which everyone considered superior to his own. Giorgione had sulked. Titian by now was too well established, and far too busy, to worry about rivalry, especially from a painter he knew to be his inferior. Alas, we cannot judge either of their frescos because the loggia was destroyed in 1571 to make way for the one designed by Palladio that we see today.

Alfonso invited Titian to spend that Christmas of 1521 with him in Ferrara and to bring with him the Bacchus and Ariadne, which he could finish over the holidays. Titian, caught off his guard, excused himself, pleading pressure of work. He then went off to Treviso to spend Christmas there, perhaps with the Zuccato family. Tebaldi, realizing that it was useless to expect Titian to change his plans, took it upon himself to make another offer, one that he was certain would please the duke and that he hoped Titian would find too tempting to refuse. He remembered that Titian had once mentioned a wish to visit Rome. Alfonso would be travelling to Rome to kiss the feet of the new pope as soon as one was elected. If Titian would come to Ferrara in good time for his departure Alfonso would be glad to take him along. On 26 December Alfonso responded enthusiastically to Tebaldi’s latest stratagem:

M. Jacomo. If you had the vision of a prophet you could not have said anything more true to Titian. Nevertheless, the minute we have heard news about the new pope we wish to go in person to kiss the feet of His Holiness, assuming that nothing prevents us. So please advise Titian that if he wants to come he must come quickly. We would dearly like his company, but tell him he must not speak of this matter to anyone. And perhaps he should dispatch our picture at his earliest opportunity because there will be no question of his doing any work on our journey.

On 3 January 1522 Tebaldi advised his master that Titian had returned to Venice, but was indisposed with a fever. And yet, when he visited him the next day, he found that he had no fever at all. In fact he looked well, ‘if somewhat exhausted’:

But I suspect that the girls whom he often paints in different poses arouse his appetite, which he then satisfies more than his delicate constitution permits; but he denies it. He says that as soon as he hears the news that a new pope is elected he will, if nothing else prevents it, take a barge and come [to Ferrara] looking forward to accompanying Your Excellency to Rome. But I think he will not bring with him the canvas of Yours. He may change his mind, but he won’t confirm it.

The girl who was exhausting Titian at the time of Tebaldi’s visit to his studio may have been Cecilia. Titian had brought her to Venice from Perarola di Cadore, the hamlet where the ancestral Vecellio sawmills were located, and where her father was the son of a barber, a respectable profession at a time when barbers were qualified to carry out minor surgical procedures. She was living with Titian in the terraced house behind the Frari that he rented from the Tron family,9 and she may already have been pregnant with their first child. Since we know that Titian used friends and members of his households as models we are free to speculate that Cecilia might have been the model for his Flora, that lovely buxom girl, whose skin has the glow of healthy pregnancy and who points to the bulging waistline under her white shift.10 Perhaps he used her face again for the Venus Anadyomene.11 Titian altered that head during the painting, and she has the same colouring and features as the Flora.12 But the most that can be said with certainty is that Flora’s features and colouring were of a type Titian favoured over a number of years and which we see again in the twinned women in his earlier Sacred and Profane Love, in the Young Woman with a Mirror and in the Madonna in the Pesaro altarpiece.

Neither Titian nor Alfonso travelled to Rome in January. Although Leo’s cousin Giulio de’ Medici had been the favourite for the papal throne, it was an outsider, the dour and scholarly sixty-three-year-old Dutch cardinal Adrian Dedal of Utrecht, who was elected by the conclave as Pope Adrian VI on 9 January. Adrian, however, did not arrive in Italy until August. Tebaldi meanwhile thought up a more practical suggestion, one more likely to appeal to Titian’s circumstances and temperament. On 4 March he wrote to the duke that he had not bothered to report his many conversations with ‘maestro Titiano’, who always assured him that he would finish the Bacchus and Ariadne, as he had done yet again that very day, when ‘he told me that he wanted to put aside some other pictures and finish Your Excellency’s’:

But, my lord, I doubt very much that he will do so, for he is a poor fellow and spends freely, so that he needs money every day and works for anyone who will provide it, at least as far as I can see. Thus when some months ago Your Excellency sent him those twenty-five scudi, he began the picture on which he had up to that time done nothing, and he worked on it for many days and made good progress, and then left it as it is now. It is my opinion therefore that it would be a good idea if Your Excellency would send him some scudi, so that he has some spending money and can satisfy your wish to have the said painting.13

But the painting was still not ready in June when Titian told Tebaldi he wanted to redo some figures that were not up to standard. When he had done that work he would take it to Ferrara and stay there until it was completed. But, no, he couldn’t name the date. And then he had the presumption to ask a favour of Tebaldi. Titian had a Venetian friend who wanted to go hunting for birds on the banks of the Po, purely for his own pleasure, certainly not for profit. Would Tebaldi be kind enough to solicit a hunting licence from the duke for his friend and a servant? Tebaldi claimed to be reluctant to request a privilege that was rarely granted to outsiders. Titian, who had reason to be optimistic about the duke’s reaction to any suggestion that might hurry him along, assured the ambassador that when he had received such a special indication of the duke’s goodwill he would be so happy that he would put all of his skill and ingenuity into drawing and colouring a pair of figures in the Bacchus and Ariadne. Tebaldi, who was not amused, told him to stop joking and just take the painting to Ferrara as soon as possible.

These were strenuous times for a painter who was rarely able to work fast. Titian had resumed work on Jacopo Pesaro’s altarpiece in the Frari, which he seems to have put aside shortly after his first payments in 1519. In 1522 he received further instalments in April (ten ducats, six lire and four soldi), May (the same amount) and September (ten ducats). As the only major painter working in Venice and the recipient of a broker’s patent he was required by the government, furthermore, to paint his first portrait of a doge, the octogenarian Antonio Grimani, who had succeeded Leonardo Loredan in July 1521, but died after only two years in office. Meanwhile he could not ignore a resolution passed by the Council of Ten on 11 August 1522, a copy of which was delivered to his door by a messenger. The Ten demanded that he complete the canvas ‘fourth from the door in the Hall of the Great Council’ before the following 30 June under pain of losing his chances of a broker’s patent as well as all the advances received so far from the Salt Office. The painting in question was the Submission of Frederick Barbarossa before Pope Alexander III, which Giovanni Bellini had not finished before his death. This time Titian took the threat seriously, and began to spend his mornings, so he informed Tebaldi, working in the palace.

Meanwhile Titian had put his best efforts into Averoldi’s polyptych for Brescia, which was unveiled over the high altar of Santi Nazzaro e Celso on the saints’ feast day in late July 1522.14 Although he had grumbled to Tebaldi about his payment of 200 ducats it was in fact one of the most expensive altarpieces of the time. The St Sebastian that Alfonso d’Este had coveted is the largest figure. The central Risen Christ is another of his most powerfully moving figures; and the Annunciating Angel is one of his most charming and frequently reproduced angels. To achieve the particular black of the donor’s robe as he kneels with the titular saints Titian used no fewer than ten layers of paint and glazes. Since he had accepted the commission it had grown from three to five panels, and the biggest challenge was integrating five separate paintings into a harmonious single polyptych. It was one that he triumphantly met, as he must have thought himself when he signed it ‘TICIANUS FACIEBAT/MDXXII’ (Titian was making/1522).15 This was the first time Titian used the reference to Pliny indicating that great art is never finished.

Alfonso’s Bacchus and Ariadne was still not ready at the end of August, and when Titian showed no signs of moving from Venice there were more irate messages from the duke. On 31 August Tebaldi hastened to Titian’s studio to see the much-coveted painting, and wrote to the duke the only specific description we have of a work by Titian in progress.

Yesterday I saw Your Excellency’s canvas, in which there are ten figures, the chariot, and the animals that draw it; and maestro Titian says that he thinks he will paint them all as they are without altering the poses. There will be other heads and the landscape but he says they can be easily finished in a short time, at the longest by next October, when he will have finished everything, in such a way that if Your Excellency does not want additions, the whole thing will be finished and finished well in ten or fifteen days.

Titian, he continues, begs His Excellency to put aside his anger against him, which has made him so afraid that he says, ‘not joking and with a solemn oath’, that he will never again come to Ferrara ‘without a safe conduct in writing’ from the duke. Nevertheless, he does greatly regret having aroused such anger and will finish the work in Ferrara by mid-October. ‘He has said to me three or four times that if Christ were to offer him work he would not accept anything if he had not finished your canvas first.’

But to Tebaldi’s embarrassment Titian did in fact fail once again to keep his word with Alfonso. When he had not met the deadline he had promised to keep with a solemn oath, Tebaldi reported to the duke that he had tried to put the fear of God into Titian with tremendous bravado in the name of His Excellency. But Titian had coolly explained that he had had to change two of the female figures and certain nudes, which he would finish by the end of the month. He would bring the picture then, and finish off some heads and other details in Ferrara. He couldn’t come now because here in Venice he had the convenience of whores and of a man who would pose for him in the nude. He was working in the Hall of the Great Council in the mornings, but would devote the rest of his time to the duke’s picture. At the end of the month Tebaldi wrote that Titian had promised that he would embark for Ferrara without fail on the following Sunday evening and had asked him to arrange for a barge. Giddy with relief, he had told Titian that he would provide ‘one, two, or more barges, as many barges as he wants’, and that he was free to bring along his girls if their presence would calm his spirit. But the duke was to be disappointed yet again. The autumn passed, and Titian failed to take up Tebaldi’s desperate offer. He had received the twenty-five scudi by 2 December, and on the 5th he renewed his promise to visit Ferrara and indicated that he might or might not be induced to bring a figure of a woman that he had finished. Once again he spent Christmas in Treviso, probably with the Zuccati.

Alfonso’s Bacchus and Ariadne was delivered to Ferrara over Christmas by Altobello Averoldi, who had been appointed governor of Bologna and had offered to drop it off on his way to take up his post. Titian, then, may not have been present when his painting, still unfinished, was unpacked from its crate. Although Alfonso had paid for the full range of the most expensive pigments, the overall effect would not be achieved until Titian applied the final scumbles and glazes (most of which have been removed in subsequent restorations).16 Nevertheless those of us who have stood entranced in front of the Bacchus and Ariadne at the London National Gallery may imagine the duke’s reaction to his first sight of the picture that had haunted his dreams for more than two years. This time, possibly at Alfonso’s suggestion – or perhaps at Ariosto’s – Titian had mixed his mythological sources. The subject, like that of the Worship of Venus, was taken from Philostratus. In the Imagines, however, Ariadne was asleep when Bacchus arrived on the island of Naxos, and his unruly followers were ordered to tiptoe in silence so as not to awake her. Titian would certainly have preferred the more dramatic versions as told by Catullus and Ovid, which permitted him to depict the clashing cymbals and general mayhem of the trail of bacchants accompanying their leader on his way back from India. Bacchus, the embodiment of youth, beauty and enjoyment, sees the despairing Ariadne, who has been abandoned by Theseus. He leaps from the side of his chariot. Their eyes meet. Ariadne is at once frightened and seduced. He promises that she will be immortalized as a constellation of stars, which appear in the sky above her. In the exact centre of the foreground the drunken baby satyr, dragging the bleeding head of a dismembered bullock like a toy, gives us a knowing stare. (Titian softened the glaze on one of his eyes with the tip of a finger.) The tigers, which Ovid said might frighten the girl, are wittily transformed into cuddly adolescent cheetahs, portraits of two of the hunting animals in Alfonso’s menagerie. The bearded bacchant on the right is one of Titian’s most obvious quotations of the Laocoön,17 this time snakes and all, and is taken from the same side view he had used for Averoldi’s St Sebastian. Ariadne’s face could be a portrait of Laura Dianti, but the broad-shouldered model for her body, the pose of which was much revised, looks more like a man’s.

Titian’s two assistants delivered another consignment of his effects by 30 January 1523 when the ducal accounts record payments for a barge that had delivered a painting on panel18 sent from Venice by ‘Maestro Titiano to His Most Illustrious Highness’, and for the porters who had carried the panel and Titian’s trunk from the port of Francolino to the castle. His assistants were lodged at the castle inn, where they consumed twenty-four meals, for which the host was reimbursed from the Este bank on 7 February. Titian meanwhile had made a second brief visit to the court of Alfonso’s nephew, Federico Gonzaga,19 the twenty-three-year-old 5th Marquis of Mantua. He went with Alfonso’s permission – it was normal practice for the two courts, which were so closely related by blood and geography, to exchange artists – but on the understanding that the completion of Bacchus and Ariadne and other works for the duke must take priority and he could therefore not stay for long in Mantua. He set off from Venice for Mantua on 26 January, carrying with him a letter of recommendation from Federico’s ambassador in Venice, Giambattista Malatesta:

Most Illustrious and Excellent Signor and my most cherished patron. The present bearer is maestro Ticiano, most excellent in his art, and also a modest and gentlemanly person in every respect, who has postponed many of his works of the moment to come to kiss the hand of Your Excellency, as you have deigned to request me. Whereby I cannot do otherwise than recommend him.

The letter was a formality. Federico had been asking Malatesta to invite Titian to his court since Christmas of the previous year, when he had hoped that ‘Maestro Tutiano pittor’ might spend the holidays with him. Titian had refused but promised the ambassador that he would certainly be in Mantua to kiss the hand of the marquis by the end of the first week in January. When he finally reached Mantua, late as usual, the marquis greeted him warmly, and before he reluctantly allowed him to depart for Ferrara ordered some work, which he seems to have wanted or needed to be done very soon. There is a note of urgency in the letter he wrote to his uncle on 3 February for delivery by Titian along with some presents; and its tone is very different from Alfonso’s temper tantrums:

Most Illustrious and excellent Lord Uncle – Having asked Titian, the bearer of these presents, to execute certain works for me, he declares that he cannot serve me at present because he has promised to do some things for Your Excellency which will take a long time. For this reason I send him to attend you. But I beg you to send him back at once to expedite the work that I want from him, which will take only a few days, and as soon as he has done that he will return to the service of Your Excellency, who will have done me a most singular favour, and to whom I stand greatly recommended.

Federico Gonzaga had come of age less than two years before Titian’s visit. Twenty-four years younger than his uncle Alfonso, he was a more sensitive, more self-indulgent and altogether more polished character. While he was still under the regency of his mother Isabella d’Este, Baldassare Castiglione, who would later be Federico’s ambassador in Rome, praised him in an early version of The Courtier as one of the most gifted of the sons of illustrious lords, ‘who may not have the power of their ancestors but make up for it in talent … In addition to his excellent manners and the discretion he shows at so tender an age he is said by those in charge of him to be wonderful in wit, desire for honour, courtesy and love of justice.’ He was a godson to Cesare Borgia, and as a boy of only ten had been sent, as a pledge for his father’s loyalty, to the magnificent court of Julius II, where he was pampered and indulged by the warrior pope and his cardinals. He developed a taste for luxury, especially the work of goldsmiths and jewellers, and his interest in painting was stimulated by the masterpieces by Michelangelo who was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and by Raphael, who made a sketch of him in armour and included a portrait of him in the School of Athens. At seventeen his father had contracted for him a dynastic marriage to Maria Paleologo, the eight-year-old daughter of the Marquis of Montferrat, to be consummated when the bride reached fifteen in 1524. (By that time, however, Federico, who was a notorious womanizer, had conceived a passion for Isabella Boschetti, the wife of one of his courtiers.) He and his mother kept a palace in Venice, where they often went for pleasure and where Federico was a member of one of the companies of the hose.