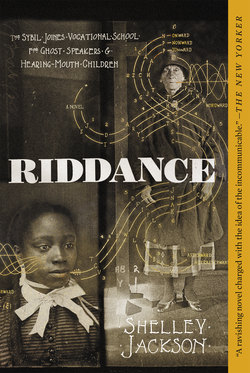

Читать книгу Riddance - Shelley Jackson - Страница 28

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLetters to Dead Authors, #2

Dear Mr. Melville,

It has come to my attention that you are dead. I wish I had known that before writing my last letter; I would have expressed myself differently. I had naturally hoped to persuade you to come to the aid of my school. A testimonial from a great man, a national treasure—

But a corpse cannot write a letter to the Times.

A corpse cannot read a letter, either. That is common sense. Perhaps I am a zany for writing this; perhaps it is true what Mrs. Brock and the other hens at the Harmonial Sisterhood said of me. But is it really so much more sensible to levitate tables, and converse with dead Lincolns, and have your likeness taken with ectoplasm pluming from your nostrils, as Victoria Littlebrow did last August in Chicago, at the home of the Beatific Twins?

Which reminds me: I hope my last letter did not give you the impression that I am one of those Very Veiled Ladies clutching at the cold hands of drowned daughters and overlooking the ice bucket in the medium’s lap. My researches are driven by a passion for inquiry, not by wishful thinking, and are pursued on the very latest equipment, as the Reflectograph; Communigraph; Dynamistograph, or Cylinders of Matla; and many other devices of original design.

My students receive, in addition to vocational training, a superior general education. Here history is taught by people who lived it, Boolean algebra explained by Boole himself. Our students might study thermodynamics with Jim Maxwell or natural selection with Chaz Darwin. Our school is a hive of industry. Even now, from behind the paneling comes a dry, insectile chirring: my stutterers practicing their scales in the next room, under the bloodshot eye of Mr. Lieu. Some of them cannot pronounce the letter A. Some the letter B, or C, or D. And I have lately spotted (in our little town of Cheesehill of all places) an E, and scheme to bring her to us. Eventually we will silence the whole alphabet.

Do you know, once I could not pronounce my own name? It does something to a child, something I intend to do to my students. I have assigned them new names according to their gifts. You are the ’d’ms and ’v’s of a new Eden, I tell them.

Why do I continue to trouble your repose, you may ask: Are there no living authors to whom I can turn for guidance or companionship? Perhaps I am more comfortable with the dead than the living, though there seems to me scant difference between a dead and a living writer. This is not so much because dead writers seem alive still in their words, as because the living ones seem already dead in theirs.

A book is a block of frozen moments—of time without time, which can nonetheless be reintroduced to time, by a reader who runs her attention over it at the speed of living. Just so does a traveler turn a landscape into a sequence of moments, in one of which she glimpses a javelina disappearing into an arroyo, in another, the fence she can hop for a shortcut home. The comparison is not frivolous: In the book, the author’s voice has become a place.

This place is the land of the dead.

I do not mean that figuratively. I consider writers my fellow necronauts, pulling on their Ishmaels and their Queequegs like mukluks and trudging across the frozen tundra of the page.

Incidentally, you would marvel if you could see me, for I am wearing a cunningly constructed device that pulls open the mouth and stretches the tongue, which in my opinion can never be too long. On the latter I am wearing a sort of costume made of paper. One of my principle communicants on the Other Side, Cornelius Hackett, said something today (through my mouth, of course) that I did not quite make out, but that may have been “little dress.” It is also possible, as one student suggested, that it was “littleness” (humility?) or even “fickleness.” Though to what in this world have I been as faithful as I have been, my whole life long, to death?

I will know soon enough if my “little dress” pleases the dead. It certainly pleases me to see, in the mirror, my neatly turned-out tongue jumping in my mouth, like a pupil at morning calisthenics. On the other hand, my shadow on the wall, wagging with the flame, is fearsome. It almost looks like the head of someone who has been partially flayed with a blunt instrument, possibly a spoo—

I just very nearly set my hair on fire with the candle! And then, in putting myself to rights, scorched the ruffle on my tongue. Let this remind me to keep my attention on the task at hand, instead of alarming myself with figments.

I should explain why I chose to make this dress out of paper and not a stouter substance. For while a fiery demise could not reasonably have been foreseen, a watery one would seem eminently likely, the mouth being a soggy sort of cotillion. But I will always choose paper when I can: it is an ideal conductive medium for spirits. I must have sensed this when, as a child, I had the habit of chewing into a cud corners torn from the pages of books.

Only yesterday, on one of my rare visits to town, the Cheesehill librarian splattered me with dung as she drove by in her motorcar, for she is grown very grand now that she is married and her husband a wealthy man.

On the whole, I am glad you are dead; every author should be dead. When I first understood that most of them are, I was a little relieved, for the idea that they might be paring their corns or nibbling almonds while their ghosts murmured prematurely in my ear seemed not only disorienting but a little unseemly. It is hard to yield oneself fully to communion with a person who somewhere may be singing in a saloon,

There was a fiddler and he wore a wig,

Wiggy wiggy wiggy wiggy, weedle, weedle, weedle,

He saved up his money and he bought a pig,

Piggy piggy piggy piggy, tweedle, tweedle, tweedle.

I see, sir, from the jut of your beard (I have your book propped open to your portrait), that you would not have sung such a song even when in the indiscreet condition that is life, but there is no telling what a man may do in the fullness of time and under the influence of spirits—alcoholic spirits, I mean—so it is very good that you are out of the way of temptation; I have seldom known the dead to sing. (That gives me quite a good idea, however—I must speak to our Mr. Lenore.)

But my little dress is becoming sodden and no spirits come. Do not be angry, Mr. Melville, but I wonder why you do not come? One of the ladies of the Harmonial Sisterhood chats regularly with Genghis Khan, and marvels that he speaks such good English, but I would much rather speak to you.

Sorrowfully,

Miss Sybil Joines