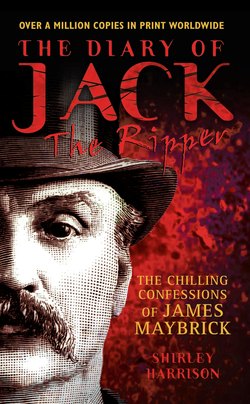

Читать книгу The Diary of Jack the Ripper - The Chilling Confessions of James Maybrick - Shirley Harrison - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PERHAPS IN MY TORMENTED MIND I WISH FOR SOMEONE TO READ THIS AND UNDERSTAND

ОглавлениеLate one May afternoon in 1889, three doctors gathered in Aigburth, a suburb of Liverpool, to conduct a most irregular post-mortem. The body of a middle-aged businessman lay on the bed, where he had died, in his plush and mahogany bedroom, while his young American widow, distraught and confused, was in a mysterious swoon in the adjoining dressing room. Under the watchful eye of a police superintendent, two of the doctors dissected and inspected the internal organs while the third took notes.

The brain, heart and lungs seemed normal and were returned to his body. There was slight inflammation of the alimentary canal, a small ulcer on the larynx and the upper edge of the epiglottis was eroded. The stomach, tied at each end, the intestines, the spleen and parts of the liver were put into jars and handed to the police officer.

About two weeks later the same three doctors drove to Anfield cemetery, where the body had by that time been buried. They arrived at 11 p.m. and, in the yellow light of naphtha lamps, stood by the fresh grave while four men dug up the coffin. Without lifting the body from its container, they removed the heart, brain, lungs, kidneys and tongue for further investigation. An eye witness reported: ‘there was scarcely anyone present who did not experience an involuntary shudder as the pale, worn features of the dead appeared in the flickering rays of a lamp held over the grave by one of the medical men.

‘What everyone remarked was that, although interred a fortnight, the corpse was wonderfully preserved. As the dissecting knife of Dr Barron pursued its rapid and skilful work there was, however, whenever the wind blew, a slight odour of corruption.’

Eventually the authorities concluded that 50-year-old James Maybrick, a well known Liverpool cotton merchant with business connections in London, had been poisoned. His death certificate issued on June 8th shockingly pre-empted the course of justice: it stated — before Florie had even been tried let alone judged — that Maybrick died from ‘irritant poison administered to him by Florence Elizabeth Maybrick. Wilful murder.’

That August, after a sensationally disorganised trial that gripped Britain and America alike, Maybrick’s 26-year-old widow, Florie, was convicted of his murder and condemned to death. She was the first American woman to be tried in a British court.

* * *

Six months before Maybrick’s death, Thomas Bowyer walked through Whitechapel, a squalid neighbourhood in London’s East End. He was on his way to collect the overdue rent of 13 Miller’s Court, let by John McCarthy to Mary Jane Kelly. It was about 10.45 a.m. on November 9th, and cheerful crowds were making their way to watch the passing of the gold coach amid the traditional celebrations that, even today, mark the annual inauguration of London’s Lord Mayor.

There was no response to Bowyer’s knock. Reaching through the broken widow, he pulled back the grubby, makeshift curtain and peered into the hovel that was Mary Kelly’s pathetic home. On the blood-drenched bed lay all that remained of a girl’s body.

It was naked, apart from a skimpy shift. There had been a determined attempt to sever the head. The stomach was ripped wide open. The nose, breasts and ears were sliced off, and skin torn from the face and thighs was lying beside the raw body. The kidneys, liver and other organs were placed around the corpse, whose eyes were wide open, staring terrified from a mangled, featureless face.

Mary Jane Kelly was the latest victim of a fiend who had been butchering prostitutes since the end of August. The killings all took place around weekends and within the same sordid square mile of overcrowded streets that was, and is, one of London’s most deprived areas. The women were strangled, slashed and mutilated, in progressively more brutal attacks.

Mary Ann (‘Polly’) Nichols, believed to be the first victim, was a locksmith’s daughter in her early forties who moved from workhouse to workhouse. Then came Annie Chapman, 47, Elizabeth Stride, 44, and Catharine Eddowes, 46. Now there was Mary Kelly, at about 25 the youngest of them all.

Hideous as these crimes were, they might have been forgotten or dismissed as an occupational hazard of the ‘unfortunates’, as prostitutes were called, had the police not been taunted by notes and clues. These came apparently from the murderer who, in one infamous, mocking letter had given himself a nickname that sent shudders through London and far beyond: Jack the Ripper.

No one in 1889 had reason to link the exhumation of James Maybrick in a windy Liverpool graveyard with that earlier blood bath in a squalid London slum, 250 miles away. Neither the police nor the medical men in Liverpool could possibly have connected the doctors’ macabre midnight dissection of a respectable middle-aged businessman and the gruesome disembowelling of a young Whitechapel prostitute. That link was finally made 103 years later, in 1992, when a newly found Diary exposed the possibility that James Maybrick was Jack the Ripper.

* * *

On March 9th of that year, my literary agent Doreen Montgomery, managing director of Rupert Crew Limited, one of the capital’s longest-established and best-respected agencies, took a call from Liverpool. It was from a ‘Mr Williams’. He said that he had found the Diary of Jack the Ripper and would like to bring it to her for publication.

She was naturally cautious. Doreen has been my agent for many years so she suggested I should be present at the meeting; she would welcome a second opinion. In fact ‘Mr Williams’ turned out to be Michael Barrett, a former scrap metal dealer with a taste for drama. He arrived in the Rupert Crew office, wearing a smart new suit and clutching a briefcase. Inside, in brown paper wrapping, was the book which was about to have such a cataclysmic effect on so many of those whose lives it touched and cause uproar in the hitherto peaceful world of Ripper historians. It appeared to be a dark blue, cross grain leather, quarterbound guard book. The binding and paper were of medium to high quality and well preserved. To judge by the evidence of the glue stains and the oblong impressions left on the flyleaf, the book had served the common Victorian practice of holding postcards, photographs, reminiscences, autographs and other mementoes. The first 64 pages had been removed. The last 17 were blank. The writer’s reference to his fear of being caught as early as page three — ‘I am beginning to think it is unwise to continue writing’ clearly indicates that what we are reading is the end of the story — not the beginning. For whatever reason the earlier text has been destroyed. Then followed 63 pages of the most sensational words we had ever read. Their tone veered from maudlin to frenetic; many lines were furiously crossed out, with blots and smudges everywhere. We were sickened by the story that unfolded in an erratic hand, reflecting the violence of the subject.

I will take all next time and eat it. Will leave nothing not even the head. I will boil it and eat it with freshly picked carrots.

The taste of blood was sweet, the pleasure was overwhelming.

Towards the end the mood softened:

Tonight I write of love.

tis love that spurned me so,

tis love that does destroy.

Finally, we read the words:

Soon, I trust I shall be laid beside my dear mother and father. I shall seek their forgiveness when we are reunited. God I pray will allow me at least that privilege, although I know only too well I do not deserve it. My thoughts will remain in tact, for a reminder to all how love does destroy… I pray whoever should read this will find it in their heart to forgive me. Remind all, whoever you may be, that I was once a gentle man. May the good lord have mercy on my soul, and forgive me for all I have done.

I give my name that all know of me, so history

do tell, what love can do to a gentle man born.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dated this third day of May 1889

I was not a Ripper historian, but even after some 40 years as a professional writer I sensed, in this rather drab looking journal, the thrill of the chase! Was it true? Was it a forgery? I listened, still suspicious, anxiously waiting for clues as Michael Barrett talked.

Those who have read the original, hardback edition of my book and the subsequent paperback editions will be aware that some details of Michael’s recollections have changed. We have been accused of altering the story to meet objections and so compounding a lie with a lie. Quite the reverse. Research is organic, it is not static. Over the five years since my first meeting with Michael I have learned a great deal. New information emerges every week and I have revised some of my interpretation of events accordingly, not to pervert the course of history, but to come nearer to the truth.