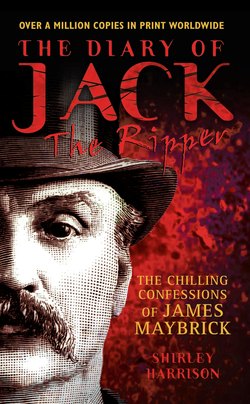

Читать книгу The Diary of Jack the Ripper - The Chilling Confessions of James Maybrick - Shirley Harrison - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MY HANDS ARE COLD, MY HEART I DO BELIEVE IS COLDER STILL.

ОглавлениеIn Liverpool I found a city in which neatly painted Victorian terraces march in orderly rows over the hill, which drops down through acres of council houses to Albert Dock and the River Mersey. Windows were boarded up, shops and offices were derelict and beer cans sprouted on wasteland. Yet the pubs were noisy and full behind their ornately patterned glass and shiny, tiled façades. Liverpool, once a prosperous city, was struggling to survive, its heart torn out by poverty and unemployment. The ships that once served the busiest port in Britain had long since gone.

The city is surrounded by a protective cloak of beautiful parks and fine suburbs. There, the ornate mansions of wealthy Victorian merchants stand, proud mausoleums, recalling an energetic past but occupied today by students and their landladies and the elderly residents of eventide homes. One such suburb, Aigburth, lies to the south of the city centre, on the banks of the Mersey.

Battlecrease House is, as it was when the Maybricks lived there, half of an impressive mansion, built in a time when horse-drawn carriages bumped along the unpaved lane. Now known simply as 7 Riversdale Road, Battlecrease House is a 20-roomed, mushroom-coloured house set well back from the road. It stands opposite the Cricket Club of which James Maybrick was an enthusiastic member. Riversdale Road runs from the Aigburth Road down to the banks of the Mersey and views across the water to the distant Welsh mountains are uninterrupted still.

Maybrick was probably aware of the rumours that a murder had taken place at the house many years before. Nevertheless he moved in, with his young American wife and their two children. In 1889, not much more than a year later, sightseers gathered by the entrance — as they still do — pointing curiously at the upstairs windows of the room where Maybrick died. Some broke twigs from the shrubs surrounding the garden, as mementoes, unaware that the house could have another, even more shocking claim to notoriety.

James Maybrick has never before been associated with the case of Jack the Ripper and, like Michael Barrett, I found myself drawn to retrace the steps of the man whom I suspected had confessed to terrorising London and shocking the world. I walked along the narrow alley at the side of the former grounds of Battlecrease House which leads to tiny Aigburth station where Maybrick had boarded the train into town.

The gravel crunched as I walked up the driveway. I knocked at the door once used by the Maybricks and found myself talking to Paul Dodd, a primary school teacher who grew up in Battlecrease House. As I walked with him around the still splendid rooms, it was easy to imagine the whispered gossip of servants below stairs, to conjure up the immaculate figure of Maybrick himself, with his sandy hair and moustache, striding down the drive, and the coquettish Florie, the sun lighting her golden hair, reading romances in the conservatory.

The house has suffered structurally over the years. It was the only building in the road to escape the bombs of World War II, but was damaged by a landmine, and then by an earth tremor in 1984. A falling tree destroyed the conservatory. Even so, little imagination is needed to reawaken the past.

Through the reception hall and the dining-room, with its stained-glass windows picturing water birds, is the ballroom that opens on to the garden. Intact are the beautiful, ornate ceiling mouldings and the Italian marble fireplace with its exquisite carved grapes and large mirror above. Up the splendid oak staircase were rooms for guests, family and staff, a nursery for the children. Overlooking the cricket pitch is the rather sombre bedroom where Maybrick died. Today it is Paul Dodd’s sitting room.

Later that day I also paced the ‘Flags’, the vast open forum in the centre of Liverpool that was once the hub of Britain’s cotton industry, and visited the grave where Maybrick is buried. The large cross that once capped the headstone was, mysteriously, missing and on a return visit in February 1997 I saw that the stone had been desecrated further by graffiti and a serious attempt to smash it in two.

* * *

At the time of Maybrick’s birth there had been Maybricks in Liverpool for 70 years. They hailed from the West Country and one branch settled in the Stepney and Whitechapel area of London’s East End. Later, when unemployment became bad, some moved on to the busy port of Liverpool.

The parish church of St Peter, in the centre of Liverpool had long been a focus for James’s well-respected family. There had been Maybricks at the organ, Maybricks on the parish council and, when James was born on October 24th 1838, his grandfather was parish clerk.

St Peter’s was consecrated in 1704 as the cathedral church and, according to the Liverpool Courier, was the first building in Church Street, ‘originally surrounded by a picturesque belt of stately elms whose foliage harmonising with the summer livery of hedgerows and the floral beauty of the meadows, completed the charm of rural peace.’ A somewhat different view of the church which dominated so much of Maybrick’s childhood was that it was ‘plain almost to ugliness.’ Inside, the building was lofty, dark and oppressively sombre.

James’ christening, on November 12th, must have been a particularly happy affair for his parents, William, an engraver, and Susannah, who had already lost a four-month old son the year before. They decided to follow the Victorian custom and name the new baby James, after his dead brother. James’ older brother, William, was then aged three.

By the time James was six, his grandfather was dead and his father had succeeded him as parish clerk. Yet despite their childhood involvement with St Peter’s and respect for Victorian convention, none of the Maybrick brothers remained churchgoers as they grew up. Interestingly, though William and James were married in church, the three younger boys defied convention and preferred the registry office.

The family was living at 8 Church Alley, a narrow lane in the shadow of St Peter’s that ran into busy Church Street. It was only a few seconds walk from the road whose name was later to play so large a part in the story — Whitechapel. This Whitechapel, in contrast to its London namesake, was a fashionable shopping street. Just around the corner was the Blue Coat Hospital, a school for poor boys and girls. In Church Street itself James could linger at the Civet Cat, a nick-nack shop that sold exciting foreign toys. Or he could dream of faraway places while peering in the window of Mr Marcus the tobacconist, who ran flag-bedecked train excursions from Liverpool to London.

With the arrival of three younger brothers, Michael, born 1841, Thomas, born 1846, and Edwin, born 1851 (another brother, Alfred, had died at the age of four in 1848), the family moved to a more spacious house around the corner: 77 Mount Pleasant. They led a simple life, with no staff until after James left home, when the 1861 Census credits them with a house-servant named Mary Smith. Nothing is known about the parents’ influence and personality and little about the boys’ childhood or schooling. James probably attended Liverpool College, like Michael, but records were lost during World War II. We do know the boys threw themselves into sport, especially cricket.

However, there were other, more sinister entertainments on tap in the area of the Maybrick family home. Just round the corner, in Paradise Street, was the notorious Museum of Anatomy, reputed to contain the greatest number of preserved anatomical specimens in Britain. In 1850, the year that James was twelve, a four-wheeled landau had driven up Lime Street carrying one ‘Dr’ Joseph Thornton Woodhead, who had just arrived from America with 750 waxen models of anatomical parts and genitalia. The heavily loaded cab overturned, spilling its grisly contents into the street and Dr Woodhead decided, on the spot, to rent nearby premises for their display. In James Maybrick’s young days, the Museum of Anatomy became one of Liverpool’s most popular and shocking ‘sights’. We looked at the catalogues for 1877. They surround the exhibition with typical Victorian religious and moral justification. ‘Man know thyself’ was the legend over the door. Ladies were admitted for only three hours on Tuesday and Friday afternoons. Gentlemen were admitted at all other times. They were warned: ‘If any man defile the Temple of God, him will God destroy.’

These exhibits, intended to ‘advance science and learning’, included freaks of nature and a section on masturbation labelled as ‘self pollution — the most destructive evil practised by fallen man.’ There were full-sized models of operations on the brain and stomach and of a hysterectomy, ‘a young lady in the act of parturition’ and a man ‘discovered in the family way.’ It would not have been diffiult for any visitor to pick up rudimentary anatomical knowledge. I remembered that Nick Warren, editor of Ripperana magazine and himself a surgeon, believes that the Ripper must have had anatomical experience, though whether he was actually a doctor is disputed.

The museum was not closed until 1937 when it was removed to Blackpool and finally, most strangely, to the seaside resort of Morecambe Bay on the Lancashire coast. There, it was re-opened by former Madame Tussaud’s employee, George Nicholson, alongside a waxworks display which included the usual range of historic figures, including, of course, Jack the Ripper. It was here, during the late 1960s that another notorious killer — Peter Sutcliffe, ‘The Yorkshire Ripper’ — spent hours, peering through the peepholes of the Torso Room at the sordid, offensive and by then seedily dilapidated models. There were to be many occasions over the next few years that I sensed the spirits of Peter Sutcliffe and James Maybrick walking side by side.

* * *

From an early age, according to a later profile in The New Penny magazine, Michael was the shining star with the musical gift of ‘harmonious invention’. At the age of 14, one of his compositions was even played at Covent Garden Opera in London and he was awarded a book of sacred music for his performance in the choir of St George’s Church. The dedication reads: ‘Presented to Master Michael Maybrick as a token of regard for his musical perception.’

He was organist at St Peter’s church between 1855 and 1865. William and Susannah encouraged Michael to study and in 1866 he went to Leipzig where it was discovered that he had a fine baritone voice. From there he moved on to the Milan Conservatoire. He made his London debut as a singer in 1869 and appeared with the National Opera Company at the St James’ Theatre in October 1871. He went on to sing during the inaugural season of the Carl Rosa Operatic Company and there is reason to believe that he, and possibly James, had friendly links with the Rosa family. Michael was present at the funeral of Parepa Rosa in 1874. James Maybrick’s physician in New York was a Dr Seguin, whose family pioneered opera in America and were related to the Rosas.

Michael gave himself the stage name Stephen Adams and formed a partnership with the librettist, Frederick Weatherly. Together they wrote hundreds of songs such as ‘Nancy Lee’ and ‘A Warrior Bold’. By 1888 Stephen Adams was Britain’s best-loved composer. ‘The Holy City’, which he wrote in 1892, sold around 60,000 copies a year from publication and remains a firm favourite today. Ironically, he also later wrote a lively ditty, ‘They all Love Jack’.

For his siblings, Michael was a hard act to follow. William became a carver and gilder’s apprentice. Thomas and Edwin went into commerce. By 1858 James Maybrick had gone to work in a shipbroking office in the capital. That period of his life has been a blank to us — until now.

* * *

In 1891, two years after Florence’s trial, Alexander William MacDougall, a tall, distinguished, if loquacious, Scottish lawyer, published a 606 page Treatise on the Maybrick Case in which he asserted, among many other things, that, ‘There is a woman who calls herself Mrs Maybrick and who claims to have been James Maybrick’s real wife. She was staying on a visit at a somewhat out of the way place, 8 Dundas Street, Monkwearmouth, Sunderland, during the trial; her usual and present address is 265 Queen’s Road, New Cross, London SE.’ No. 265 is still there, now a shadow of its Victorian elegance. It was a substantial property with a garden much larger than its neighbours. MacDougall also claimed that Maybrick was known to have had five children prior to his marriage to Florie.

Who was the mysterious ‘Mrs Maybrick’? Census records, street directories and certificates of birth, death and marriage can resurrect the skeleton of any life long after it is over. But it is a long, slow process, fraught with problems, since form-filling is not always accurate and very often dates and details are incorrectly given. Census records for 1891 were not released until January 2nd 1992, according to British custom. Only then could the truth of MacDougall’s assertion be established. Only then was it possible to fill in some of the details of Maybrick’s secret life in London.

We found those details and for the first time established the names of the inhabitants of 265 Queen’s Road. They were Christiana Conconi, a 69-year-old widow of independent means from Durham, her surprisingly young daughter, Gertrude, aged 18, and a 13-year-old visitor. There were two other persons in the household: a lodger named Arthur Bryant and Christiana’s niece, Sarah Robertson, single, listed as aged 44 from Sunderland, County Durham. We realised that these ages did not tally with certificates we unearthed later. Christiana was more probably 74 and Sarah 54.

Was Gertrude really Christiana’s child? We have been unable to unearth a certificate to establish the true parentage of Gertrude, who gave her name on her marriage certificate in 1895 as Gertrude Blackiston otherwise Conconi. Her father is there said to be George Blackiston, deceased, Admiralty Clerk.

Gradually the story of Sarah Ann Robertson/Maybrick unfolded. She was first found in 1851, at the age of 13, living with Aunt Christiana at 1, Postern Way, Tower Hill, which runs into Whitechapel. Christiana’s father was Alexander Hay Robertson, a general agent, who died in 1847. That same year she married Charles James Case, a tobacconist, their residence being 40, Mark Lane which lies near Tower Hill between the City of London and Whitechapel.

James Maybrick went to London in 1858 and it seems probable that since shipbroking tends to centre on the City itself, this was where he met Sarah Ann. Charles Case died in 1863 and three years later Christiana remarried. Her new bridegroom was a paymaster in the Royal Navy named Thomas David Conconi. Their address was said to be 43, Bancroft Road. One of the witnesses at their wedding signed her name ‘Sarah Ann Maybrick’.

In 1868, Thomas Conconi added a codicil to his will: ‘in case my said wife shall die during my life then I give and bequeath all my household goods furniture plate linen and china to my dear friend Sarah Ann Maybrick, the wife of James Maybrick of Old Hall Street, Liverpool, now residing at No 55 Bromley Street, Commercial Road, London.’

This was the house then occupied by the Conconis. Whether the codicil means that Maybrick was also living with the family is unclear. But according to the 1871 census, Sarah Ann, listed as a ‘merchant’s clerk wife’ [sic] was there. James was not. The street still exists, its modest two-storey houses restored in 1990 are now framed by shiny black railings. Number 55 was demolished for redevelopment after World War 1. Turn right at the end of the street on to Commercial Road and it is but a brisk ten-minute walk to Whitechapel, the scene of Jack the Ripper’s murders.

At Wyoming University, amongst the file of handwritten notes by Trevor Christie, author of ‘Etched in Arsenic’, was one headed ‘Russell’s Brief’. Russell was Sir Charles Russell who later became Florie Maybrick’s leading counsel. It said of James:

At the age of 20 (1858) he went to a shipbroker’s office in London and met Sarah Robertson, 18, an assistant in a jeweller’s shop, she lived with him on and off for 20 years. Her relatives thought they were married and she passed as Mrs M with them. They had five children, all now dead.

Author Nigel Morland, who wrote This Friendless Lady (1957), claims that two of these offspring were born after James’ marriage to Florie. However no source is given for this information and neither have we ever unearthed a marriage certificate for James and Sarah.

When Thomas Conconi died in 1876, at Kent House Road, Sydenham, South London, ‘S. A. Maybrick niece’ of the same address was the informant. When Christiana herself died in 1895 at Queen’s Road, Sarah once again signs herself Sarah Ann Maybrick. But she is listed in the 1891 census as Robertson. However at the time of her own death on January 17th 1927, the records refer to ‘Sarah Ann Maybrick, otherwise Robertson, spinster of independent means of 24 Cottesbrook Street, New Cross.’ She was then living with William and Alice Bills. She was buried, un-named in a common grave in Streatham, London.

In 1995 Keith Skinner, hot on the trail for Paul Feldman, went to meet Alice’s daughter, Barbara. She remembers that Sarah was known in the family as ‘Old Aunty’ and that she was a lonely, sweet old lady who was very good with children. Barbara showed Keith a large Bible which had been given by Sarah Ann to Alice. Inside was written, ‘To my darling Piggy. From her affectionate husband J.M. On her birthday August 2nd 1865.’ Was Maybrick a bigamist?

* * *

Where was James Maybrick in 1871? He was back in Liverpool after the death of his father in June 1870. According to the 1871 census he was with his 54-year-old mother, Susannah, at 77 Mount Pleasant. He was unmarried. His occupation is described simply as ‘commercial clerk’, whereas brother Thomas was a ‘cotton merchant’ and Edwin a ‘cotton merchant/dealer’. He was in business with G. A. Witt, Commissioning Agent, in Knowsley Buildings, Tithebarn Street, off Old Hall Street. Two years later, he was still working with Witt from the same, overcrowded premises, where some 30 cotton merchants and brokers were crammed into one building. Maybrick established Maybrick and Company, Cotton Merchants, around this time and Edwin eventually joined him as a junior partner. The building was finally demolished in the late 1960s to make way for an imposing modern development, Silk House Court. Witt’s main offices in London, which Maybrick visited from time to time, were in Cullum Street, on the boundaries of the City and Whitechapel.

It was a rough world, vigorously characterised in 1870 in the April 30th edition of the local magazine, Porcupine. An article headed ‘Cotton Gambling’ described the ever-more unscrupulous world that had attracted Maybrick. A once prestigious trade changed almost overnight after the cotton famine that followed the American Civil War; it became a business open to ‘anyone, with no capital whatever, anyone with a shadow of credit’, reported the magazine.

In 1868 a system of ‘bear’ sales had been introduced which was similar to that of the London Stock Exchange. This involved ‘selling cotton you have not got in the hope you may cover the sale by buying at a lower price at a later period.’ It brought to the market an element of pure gambling. ‘It is to be regretted’ noted Porcupine that ‘the Cotton Brokers’ Association should have given their sanction to this system of trade and thus lower the tone and character of the market.’

Maybrick was an opportunist who thrived in this world of ruthless competition. In 1874, when he was 35, he went off to start a branch office in the newly booming cotton port of Norfolk, Virginia. Like many others, he divided his time between London and America, working in Virginia during the picking season from September to April, then returning home to Liverpool in the Spring.

Norfolk had been ruined by the Civil War, but its recovery had been energetic. One third of the town’s 37 square miles was water-logged, especially round the mosquito-infested Dismal Creek Swamp. To encourage foreign investment, a piped supply of fresh water was needed. So the water system was modernised and the improved conditions coincided with the opening of the railway connecting Norfolk with the cotton growing states of the Deep South. The town was transformed into a successful international port, nearly half of whose ships plied between Liverpool and America.

In the year that Maybrick arrived in Norfolk, the town’s Cotton Exchange was set up, giving rise to a tidal wave of commerce back and forth across the Atlantic. Three years later, while Maybrick was living in York Street with Nicholas Bateson and a negro servant, Thomas Stansell, he caught malaria. When the first prescription of quinine did no good, a second, for arsenic and strychnine, was dispensed by Santo’s, the chemist on Main Street.

‘He was very nervous about his health,’ recalled Bateson, when he later testified for the defence at Florie’s trial. ‘He rubbed the backs of his hands and complained of numbness in his limbs. He was afraid of paralysis. The last year I lived with him he became worse. He became more addicted to taking medicines.’

When it was his turn to give evidence, the servant Stansell remembered running errands for Maybrick during their time in Norfolk. ‘When I brought him the arsenic, he told me to go and make him some beef tea… he asked me to give him a spoon… he opened the package and took a small bit out. This he put in the tea and stirred it up.’

Stansell was surprised at the quantity of pills and potions in Maybrick’s office. ‘I am,’ the cotton merchant once told him ‘the victim of free living.’

Maybrick’s constant companion at this time was Mary Howard (also described as Hogwood), who kept one of the most frequented whorehouses in Norfolk. Years later, Mary pulled the rug from under Maybrick’s reputation. She gave a deposition to the State Department in Washington in which she said:

I knew the late James Maybrick for several years, and that up to the time of his marriage [to Florie] he called at my house, when in Norfolk, at least two or three times a week, and that I saw him frequently in his different moods and fancies. It was a common thing for him to take arsenic two or three times during an evening. He would always say, before taking it: ‘Well, I am going to take my evening dose.’ He would pull from his pocket a small vial in which he carried his arsenic and, putting a small quantity on his tongue, he would wash it down with a sip of wine. In fact, so often did he repeat this that I became afraid he would die suddenly in my house, and then some of us would be suspected of his murder. When drunk, Mr James Maybrick would pour the powder into the palm of his hand and lick it up with his tongue. I often cautioned him but he answered ‘Oh, I am used to it. It will not harm me.’

The chemical element, arsenic, is found widely in nature, usually associated with metal ores. It has claimed innumerable victims, including, it is believed, Napoleon Bonaparte, who was possibly fatally poisoned by arsenic in the colouring of his prison sitting-room wallpaper in St Helena. But it has also had a wide variety of medicinal and other uses. For example, in the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I used arsenic as a cosmetic, applying it to her face to make it more white, just as Florie Maybrick used an arsenical preparation for her complexion. In 1786 Dr T. Fowler reported on the medical benefits of arsenic in cases of fever and sporadic headaches. Fowler’s Solution was a popular tonic in Maybrick’s time. The Greek word for arsenic — arsenikon — means ‘potent’. Maybrick, like many men of his day, believed that it increased his virility. Because he was addictive by nature, he became hooked.

* * *

The year 1880 was crucial for Maybrick, for at the age of 41 he fell in love. He was booked, as usual, to return to Liverpool aboard the SS Baltic. The Baltic was one of the White Star Line’s powerful screw-driven trans-Atlantic steamers, designed to ‘afford the very best accommodation to all classes of passengers.’ The six-day voyage cost 27 guineas.

On March 12th the Baltic, in the command of Captain Henry Parsell, steamed from New York. Among the 220 first-class passengers was the impulsive, cosmopolitan Belle of the South, Florence Chandler, known as Florie. Only 17, she was in the care of her mother, the formidable Baroness Von Roques, and they were on their way to Paris. Also on board was the ladies’ friend, General J. G. Hazard, living in Liverpool and he introduced Maybrick to them in the elegant bar.

Maybrick learned that the lively 5’ 3” strawberry blonde hailed from America’s high society. She had been born on September 3rd 1862, during the American Civil War, in the sophisticated city of Mobile, Alabama. Her mother, Carrie Holbrook, ‘a brilliant society woman’, was a descendant of President John Quincy Adams and Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase.

Among other achievements, Carrie’s swashbuckling Yankee father had founded the town of Cairo, Illinois, which Charles Dickens was to condemn after a visit in 1842 as a ‘place without one single quality, in earth or air or water to commend it.’ Darius Holbrook himself, Carrie’s father, was caricatured as Zephaniah Scadder in Martin Chuzzlewit. Her uncle, the Reverend Joseph Ingraham, had enjoyed an adventurous career as a soldier of fortune and had written blood and thunder novels.

Florie’s father, William Chandler, had been a wealthy merchant and Florie was born in the magnificent family home on Government Street (demolished in 1955 to make way for the Admiral Semmes Motor Hotel). But Florie never knew her father for he died on July 4th 1862, two months before she was born, leaving her and her older brother, Holbrook St John, fatherless. His headstone reads: ‘William G. Chandler. Gifted and good, the Joy, the Pride, the Hope and the Light of our life.’

He was only 33. The entire family was convinced that his wife Carrie had poisoned him and, although there was not a shred of evidence, Carrie was ostracised by Mobile society and moved the children away to Macon, Georgia. Six months later, she married the distinguished soldier Captain Franklin du Barry, but he too died unexpectedly, aboard ship bound for Scotland, soon after their marriage.

From then on for several years little Florie and her brother seem to have been feathers on the wind, blowing this way and that between Paris, England, New York and Cologne. In about 1869 the family lived for two years in a house called The Vineyards, at Kempsey near Worcester. A German governess was educating the children, and local residents remembered Madame du Barry as a fine, handsome woman and good company. The house was always full of visitors.

When she returned to America she entered, with gusto, the ribald social life of New York. It was a frenetic, violent often scandalous time after the Civil War, known as ‘The Flash Age’ and Madame du Barry lived it to the full. She mixed in New York society where families such as the Vanderbilts were her friends. During 1870-71, back in Europe, she was caught up in the Siege of Paris, as a result of which she fell in love again. This time it was the dashing Prussian Cavalry Officer, the Baron Adolph von Roques, who fell prey to her attentions.

But the marriage was a disaster. The couple led ‘an adventurous life’ from Cologne to Wiesbaden and on to St Petersburg, squandering money, incurring massive debts and leaving devastation everywhere they went. Even so, Florie recalled, through rose-coloured spectacles, what must have been the appallingly lonely confusion of that time. She was virtually fatherless and being lodged, as it suited her mother, with relatives and friends. Yet in her autobiography, My Fifteen Lost Years, she wrote:

My life was much the same as that of any girl who enjoys the pleasures of youth with a happy heart… My special pastime however was riding and this I could indulge to my heart’s content when residing with my stepfather, Baron Adolph Von Roques, now retired, was at that time a cavalry officer in the Eighth Cuirassier regiment of the German army and stationed at Cologne.’

Her writing reveals ingenuousness and a preference for glossing over the true facts which coloured the rest of her life. She could never face unpleasant reality and surrounded herself with cheap fiction, dreams, and, towards the end, with cats. There is no mention in her story that the Baron beat her mother and finally left her in 1879 when Florie was 17 years old.

James Maybrick must have appeared to Florie to be the perfect mix: at once the mature father figure she had never known and a worldly self-assured man with a taste for dangerous living. And she, he must have imagined, was to be his entrance into a class and a way of life that were not his by birth but to which he, nevertheless, aspired. She would bring him cachet among the socially-conscious worthies of Liverpool and, perhaps, a fortune. With breathtaking speed Maybrick swept young Florie off her feet and by the end of the voyage he had proposed. When they disembarked in Liverpool, plans were already being made for a stylish wedding the next year.

There followed a truly action-packed year. But what, I wonder, was really afoot in the Maybrick family at this time? In March 1880 James returned to tell his widowed mother of the hasty engagement. She was by now living in a boarding house run by an old friend, Mrs Margaret Machell at 111, Mount Pleasant. It seems inconceivable that she knew nothing of Sarah Ann or of the children she was alleged to have borne. Did Susannah express disapproval of his behaviour? If so, Maybrick was unmoved and by April was strolling the chestnut-lined streets of Paris with his bride-to-be.

On May 1st his mother died. He was present at her death but living at Ashley Broad Green. Her death certificate states the cause of death, curiously, as ‘Bronchitis Hepatic’.

Ruth Richardson, author of Death, Dissection and the Destitute and an expert on Victorian death certificates said: ‘This is odd. It doesn’t really make sense. I have not seen one quite like it.’ Bronchitis concerns the bronchial tract. Hepatic means ‘of the liver’. But there is nothing which accurately explains what was really wrong with Susannah’s liver. We can only wonder. Did she have a drink problem? Or had she become addicted to drugs like her son? Or could there possibly have been another, more sinister, explanation?

James’s mother was dead. She was no longer able to cast a shadow over the proceedings by revealing ‘any lawful impediment’ why her son should not marry Florence Elizabeth Chandler.

With typical delusions of grandeur, the cotton merchant arranged for the ceremony, 14 months later, to be at the suitably named St James’s Church, not in Liverpool but in Piccadilly, one of the most fashionable settings in London. At the ceremony, which was conducted by the Reverend J. Dyer Tovey, the bride wore a gown of pleated satin and ivory lace and her bouquet was of white columbines with lilies of the valley. The bridegroom, 24 years her senior, wore a white satin waistcoat embroidered with roses and lilies of the valley and a cutaway coat lined with elaborately quilted satin.

Florie’s brother, Holbrook St John, came from Paris to give her away. Although Maybrick’s brothers Edwin, Thomas and Michael were there, he must have been disappointed that there was no great enthusiasm for the match. Michael, who dominated the trio, was sceptical. Guests reported, with some justification, that he did not believe the Baroness’ tales of estates to be inherited but saw in her scheming a crafty plot to secure for herself a settled British home in her old age. (After Florie’s trial, however, she wrote somewhat fancifully to the Home Secretary that Florie had no pecuniary temptation to murder as she had assisted the family for years.)

At the time of the wedding, Maybrick had taken out an insurance policy, with Florie as beneficiary, for £2,000, which he later increased to £2,500. He also set up a trust fund of £10,000, a sum equal today to 40 times this amount, but he never paid in a penny. Florie herself had a small income of £125 a year from her grandmother’s house in New York, and there was occasional income from her late father’s lands near Mobile. There was hardly enough money to finance the kind of façade that the newly married Maybricks wished to present.

From the outset, the match was founded on deception: even the marriage certificate reveals Maybrick in his true colours. His profession he gives as ‘esquire’, his father’s as ‘gentleman, deceased’ and his residence as St. James’s.

Hardly more than a child, why should Florie suspect that his life was based on hypocrisy and deceit? Besides she had known little else herself. Nevertheless she would soon discover the awful truth that there was, already, a ‘Mrs Maybrick’.