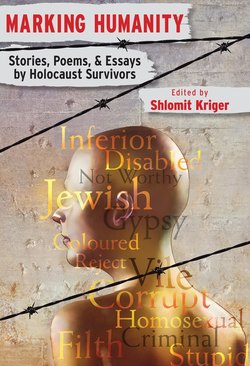

Читать книгу Marking Humanity: Stories, Poems, & Essays by Holocaust Survivors - Shlomit Editor Kriger - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

An Address to Students

ОглавлениеCommencement Speech at El Camino College in Torrance, California, June 2006

Eva Brown

When I was asked to be a keynote speaker at your graduation, I was immediately overcome by amazement and dread. I was amazed that I, a foreigner with a Grade 6 education, was chosen to inspire you, but I dreaded that I would not be able to do so.

I have spent a lot of time worrying about what I could possibly say to you that would mark this momentous occasion. What would you take away from this? Our differences are so great. You are at least 60 years my junior and have at least 14 years of education. You have mastered the electronic world of computers, digital cameras, and cell phones. I can hunt and peck on a typewriter, take photos with my old-fashioned film camera, and would never give up my rotary phone. But the biggest difference is our education; you are graduating from El Camino College, and I graduated from Auschwitz. If your enemies are your teachers, then I have learned so much from the Nazis.

To understand my message, you must first know my story. Seventy-nine years ago, I was the middle child born to a rabbi and his wife in a very small town in Hungary. My childhood was spent with my six siblings. Life was simple and carefree; we played, went to school, and celebrated holidays. But in the midst of this normalcy, German boots were marching across Europe.

In 1944 Hungary was invaded and my life was turned upside down as my father was taken away to a labour camp. My mother, younger siblings, and I were sent to the Putnok ghetto. Struggling with hunger and exhaustion, we did not think things could get worse until the cattle cars came and took us to Auschwitz—a place of unimaginable horrors and atrocities and ferocious beauty and tenacity of the human spirit. It is a bizarre coincidence that this occurred on June 9, exactly 62 years ago today, on a Friday night.

As I watched my mother and seven-year-old brother go to the gas chamber, I could not understand the depravity and madness of human beings that was reflected in Hitler’s “Final Solution.” Everyone’s past was erased. No distinction was made between doctors, lawyers, teachers, shoemakers, and honours students; each identity was reduced to a blue number tattooed on our forearms.

I found solace in the compassion of the Nazi guard that brought me food and a blanket to shield me from the bitter cold. I learned that to make myself valuable was to live. At 16 years of age, I had expected to be dating, going to school, and planning a dazzling future. Instead, I concentrated on discovering talents that would keep me alive: giving manicures, haircuts, and massages to my captors. I became an experimental scientist of my own body and mind. I learned to stay awake during the daily 4:00 AM head count that lasted three hours. I carefully balanced my food intake and energy output so I was able to finish all my work. Death was certain for those who fell asleep or fell behind in their assignments.

Even under these most dehumanizing conditions, we had choices. Some committed suicide by throwing themselves onto the electric barbed wires; others overcame starvation and sickness by sheer force of will in their determination to live. We prayed and comforted each other and vowed to make sure that one day the world would know what had happened to us.

I learned psychology—especially the art of denial and distance. I dreamt of my future; looking beyond the smoke from the gas chambers, I planned my life. I would find my family, get married, buy a house, and have children. I selected my wardrobe and menus; visions of shiny silk dresses, warm woolen coats, stuffed goose, and rich pastries filled my head as I removed gold teeth from dead prisoners. I named my smiling healthy children as I clipped the German officers’ mustaches, and I danced with my dashing husband as I filed their nails. I designed my living room and chose wallpaper for my bedroom as I worked outside in my bare feet as icy rain and snow soaked me.

After the liberation, I reunited with my father and learned that 60 members of my family had been murdered during the war. At age 17 I was struggling to regain footing in a world that had been pulled from under my feet.

I left for America with nothing but a desire to rebuild. I had lost my family, my country, and an entire way of life. But I got married, raised two children, and learned to speak a new language. I worked, paid taxes, and gave money to charity. My fellow survivors and family never talked about our experiences. It was like a bad dream that we forgot after waking up in America.

In the media the Holocaust was sensationalized or sentimentalized—it did not ring true. I remembered the fear in the young Nazi guard’s eyes as he reluctantly carried out his orders. In 1994 I saw the film Schindler’s List and was transported back to that terrible time and place. As I watched the survivors pay tribute to the man who saved them, I vowed to break my silence. After waiting 50 years, I was finally ready to tell my story. While I could not speak for the dead, I would honour their memory by sharing my experiences. Thus, I became a teller of stories.

I volunteered to give testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Institute and the Museum of Tolerance. Speaking as a Jew who comes from far away, I share my family’s story with a diverse audience: Catholics, Muslims, agnostics, the young and old. I speak of loss and redemption and of the evil that people are capable of and the good with which they can heal. The Nazis taught me the power of forgiveness. This enables me to spread my message of tolerance and respect for everyone. People from all walks of life relate to my experiences. I have found that faith and age are not the common denominators. It is by being part of the human family with the realms of emotions that touch us all—grief, terror, despair, joy—that people embrace my determination to ensure that the world will never forget what happened over 60 years ago.

My story is also about the randomness of how we’re placed in life and how we respond. The greatest lesson that I have learned is captured in a quote by renowned physicist Albert Einstein: “There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.” The fact that I am celebrating here with you today confirms that I am living the latter.

Sixty years ago, the world ignored the genocide of the Jews. Today, in America, 25 State curriculum regulations require the Holocaust to be taught and 24 others implicitly encourage it. My life has come full circle. I enjoyed so many opportunities here and always felt that I was riding on a train without a ticket. There was a larger debt to be repaid. For a family that journeyed to this country for freedom, I am finally paying the fare.

Therefore, my message to you is to never give up. Follow your dreams and always have hope. Be involved in your life through your family and friends and through public service. Play a role in making your community and country safe, so that every citizen may enjoy freedom just as I have.