Читать книгу Marking Humanity: Stories, Poems, & Essays by Holocaust Survivors - Shlomit Editor Kriger - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеThese words are being written near the beginning of the new decade of the twenty-first century. The passage of time holds meaning for all of us. It has ushered in a distinct sense of soul searching within the media and general public with reflections on the turbulent and disappointing first decade of the new millennium.

For those of us working in the field of Holocaust studies, time is not an ally but an enemy. We have attended many funerals. We have witnessed the passing of a generation. Each week it seems as if another survivor is lost and that those who remain, strong and valiant as they had once seemed, are growing older. They are more frail and giving way to the ravages of old age.

Those who were 18 years old at the time of the liberation are now well into their 80’s. A few years ago, the men among these survivors celebrated their second Bar Mitzvah,1 the 70th anniversary of their first Bar Mitzvah, which, if it were possible, would have been observed during the war in ghettos, under occupation, under siege, often clandestinely and illegally. (Lest women feel discriminated against, my point is historical. Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan introduced the Bat Mitzvah in the United States for the first time in 1922. It did not become common even in the U.S. until the post-war years; therefore, few, if any, European women were called to the Torah—Jewish Bible.)

No generation has left as voluminous a record of memoirs and testimonies as that of the Holocaust survivors. The USC Shoah Foundation Institute in the U.S. has more than 52,000 testimonies in 57 languages from 32 countries, and it is the largest of the many collections. Yad Vashem in Israel has collected testimonies for the entire post-war period. The Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University has been recording since 1979. The Holocaust Documentation and Education Center in Southern Florida began slightly afterward, and these are just a few of the collections worldwide. Memoirs come across my desk on a weekly and even daily basis. Most tell a story. Some are truly gripping. And even in the simplest of them, the stories they tell convey insight into the darkness that was experienced, as well as the world after the liberation.

But Holocaust survivors have done more than bear witness. As you will notice throughout the biographies of the featured survivors, over the past two decades survivors have become teachers throughout the world, speaking with students in schools that are large and small, secular and religious, public and private, Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and in a few cases—too few cases—Muslim. Many connect with the rich mosaic of students from diverse ethnic backgrounds: black and white, Asian and Hispanic, those from lands touched by the Holocaust, and those in the rest of world whose ancestors barely knew what was happening.

Survivors have been surprised by the way in which they have been received in American classrooms, as well as in Europe and Israel. They speak of suffering and anguish, and students see in them symbols of resilience and even triumph. While they see themselves as defined by a past, youth are moved to discover that even after such a past, involving so massive a loss, one can look forward. No longer young, they are admired for their age. Representatives of the past who often trace their roots back to places that had barely entered the twentieth century, they are respected by those who grew up in the age of computers, digital music players, the Internet, and instant messaging—not because they are of the here and now, but because they lived then and there. The encounter is remarkable.

Shlomit Kriger has compiled the writings of survivors from the United States, Canada, and abroad, survivors of the Holocaust from urban centres and rural communities. Even though their offerings are diverse and their experiences are different, they seemingly speak with one voice, of one experience.

In the immediate post-war years, when the term “survivor” was used it meant only one thing: those who had been in concentration camps. Even then there was a hierarchy, because there was an absolute distinction between death camps and concentration camps. The former were places where Jews were systematically killed—gassed upon arrival. At three such camps, the Aktion Reinhard camps of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor, almost all—99 out of 100—were killed upon arrival; only a few were kept alive to perform basic tasks of the camp: sanitation, sorting of valuables, disposal of corpses, and service to the German masters. Though about 1.5 million Jews were killed in these death camps, there were fewer than 200 survivors. (That is not a misprint; perhaps it is an exaggeration of the number of those who survived. We know of two survivors of Belzec, perhaps 100 from Treblinka, and about 50 from Sobibor who were found alive after the war.)

Auschwitz-Birkenau, which comprised three camps in one—a prison camp (Auschwitz I), a death camp (Auschwitz II or Birkenau), and a slave labour camp (Auschwitz III or Buna-Monowitz)—had many more victims as well as survivors. Some prisoners were kept alive to serve the Nazi industry that had invested heavily in slave labour and wanted to be its economic beneficiary. The Nazis presumed that a virtually limitless supply of slave labour would be theirs indefinitely.

Those who were not in camps were not regarded as survivors then, much as American World War II veterans distinguished between those who served in theatres of combat and those who did not. Child survivors were not considered survivors then. Their parents often protected themselves from fully feeling what happened to their children by saying, “What could they remember? What could they understand?” And refugees, children who had escaped on the Kindertransport (Children’s Transport)—the children of Germany and Czechoslovakia who were fortunate enough to be sent to England and be received by the country just before the war began—were not considered survivors either. Neither were the Jews who survived the war in hiding by “passing” as “Aryans” or by being sequestered by others who often risked their lives and freedom to offer them shelter. Nor those Jews who in the days after the German invasion of Western Poland or following the German conquest of Soviet-occupied Poland in 1941 went counter to the Jewish experience of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and fled east to the Soviet Union. Many were sent to Siberia, where they experienced hardships, cold, disease, famine, even death—but not systematic killing.

That was then.

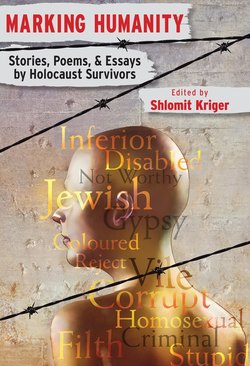

However, given the passage of time, Marking Humanity: Stories, Poems, & Essays by Holocaust Survivors includes—as it should—the writings of all who are now considered survivors. It features those who were children and others who were adults, those who were in camps and who found refuge in England or the United States, some who escaped eastward, and others who lived in hiding. Their writings and memories are varied; yet, their urge to bear witness and their sense of themselves as survivors with a unique tale to tell are the same.

One must welcome this testimony for its richness and diversity, for its inclusiveness and ingenuity. I have read prose far more than poetry and am far more confident in my assessment of an essay than a poem. Nevertheless, I find the contributors’ poetry moving. The insights expressed in a few words leave me wanting more, greater exposition and detail. Still, poetry has the ability to say much with brevity and to bring language to the edge of what can be said and what cannot be said.

As we read and as we hear survivors’ testimonies, we must think of what is said and what is left unsaid, of the spoken or written word and the silence between the words. We must also recognize how many have found healing through expression and how many of these survivors have used art and literature not only to share, but also perhaps to purge. This work offers them one such important opportunity, and we, as readers, can be part of that healing process. But we should also consider what Ludwig Wittgenstein, an Austrian philosopher of Jewish descent, once wrote: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”2 And yet, survivors have chosen with increasing frequency and intensity to abandon silence and to speak of what cannot be spoken.

We who will all too soon live without that living memory of the past must be grateful for that breech of silence even as we are respectful of the unsaid.

Michael Berenbaum

Director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical and Religious Implications of the Holocaust

American Jewish University

Los Angeles, California

1A Bar Mitzvah marks the occasion when a Jewish boy comes of age at 13 years old. According to Jewish Law, he is then obligated to observe the Commandments. For girls, a Bat Mitzvah takes place when they turn 12.

2Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 2nd ed., trans. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness (New York: Routledge, 2001), Prop. 7.