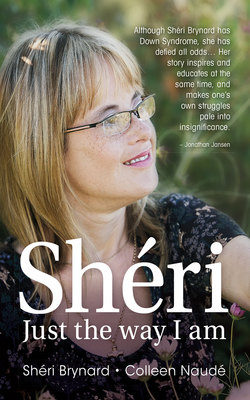

Читать книгу Shéri - Shéri Brynard - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

It is the Lord’s story and I’m part of it

ОглавлениеI was 31 years old when I started thinking that I should write my life story. So much has happened in my life.

I remember the day on the school bus when some of the big boys asked me whether I could run fast. Of course I wanted to show them that I could. When the bus stopped, I got off and ran home. I fell, blood streaming from my knees. I did not want to look back; I was crying so much. I think I heard the boys laughing.

About a year later I wanted to run the 400-metre race for the Red team at school. I was lagging far behind, but then the teacher announced: “All the members of the Red team will now finish with Shéri.” And everyone joined me for the last lap, the boys too.

But when I turned 31, I also remembered how I had met Oprah. It was in 2011 when Prof Jonathan Jansen, then vice-chancellor of the University of the Free State, invited me as guest of honour to meet Oprah Winfrey when she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the university.

And I remembered being trained as an educational assistant at Moteo College.

When I turned 31, I decided I should write down everything that has happened to me since the day I was born. Because it is a story. It is the Lord’s story and I’m part of it.

I borrowed my mother’s diaries and started reading. I looked through albums and asked my mom many questions. This is how my life started:

When my mother heard that she was pregnant, she was ecstatic. She’d always worried that she’d never be able to have children, maybe because she wanted to be a mother so badly. She was 25.

It was a pregnancy without any complications. The most interesting fact was that I moved very little during the last trimester, apparently one of the signs of Down Syndrome.

At some point during her pregnancy, someone from the Department of Genetics at the University of the Free State gave a talk to the biology class that my mother taught at Oranje Girls School. The lecturer explained what caused babies to be born with disabilities.

Afterwards, when my mother told the lecturer that she was pregnant, she said that she would never have given that talk had she known. My mother just laughed and said that it wouldn’t happen to her and, if it did, she would handle it. She was not going to worry without reason.

I found something else in my mother’s diary to be very interesting. Doctors in Germany had discovered that most women who had Down Syndrome babies had picked up a very bad cold when they fell pregnant. My mother thought about that time and remembered that she did indeed have a very bad cold. She even stayed home from work, quite unusual for her.

From around the fourth month of her pregnancy, she regularly visited a gynaecologist. Not one of the ultrasound scans revealed anything out of the ordinary. The heads of Down Syndrome babies are smaller than those of normal children, but mine, although rather small, might just as well have been that of a normal baby. The skin of my neck was also not thicker than normal.

The expected date of my birth was 20 March, but my mother was convinced that I would arrive early. She thought I’d be born on the 14th. She also thought it would be easy. My mother is always positive about everything. Years later she also thought that we would find my dad when he disappeared at the Augrabies Falls.

My mother wrote that on Sunday 14 March she was waiting for something to happen. At 11pm that evening she felt a mild contraction. She was so excited that even the neighbours could have heard her laugh! My dad took her to hospital at quarter to two in the morning and I was born an hour later.

When she heard me crying, she was certain that I was a hundred percent. The doctor let her hold me for a while, and then put me in an incubator. My mother and father then had a good look at me. The sister even said that my eyes looked just like my mother’s. My mom has huge, round eyes.

The rest of that night my mother relived everything. She wrote that she could hardly wait for her mother to arrive the next morning. I was my granny’s first grandchild, and I was given her names. At the end of my crib it said:

Name: Shéri Alida

Weight: 2,9 kg

Length: 47 cm

Day: Monday

Time: 02:52 am

Date: 15 March 1982

Place: Universitas Hospital, Bloemfontein

Doctor: Dr Wim Brummer

At around eight the following morning, my granny arrived and later the paediatrician, Dr Wilhelm Karshagen. He routinely examined all babies who were delivered by gynaecologists. He told my mother that there were problems because my muscle tone was very weak. They sent blood to be tested. The gynaecologist was concerned as well.

At about eleven my father arrived. My mother told him about the doctors’ concerns. That was when he told her that he’d noticed some Down Syndrome traits, but hoped that he’d been mistaken. That evening Dr Karshagen, who later became a friend of the family, and Dr Brummer, who still is my mother’s and my gynaecologist, gave my parents the bad news.

My father and mother were sad, but never bitter. They never asked why.

My mother wrote that the hospital staff were wonderful. She never felt that she was different, maybe just a little special with a special little girl. I was, however, different: all the other women in the maternity ward had normal babies.

My mother said that she had never before experienced so much love, from friends, family, distant acquaintances and even strangers. She received 42 bunches of flowers. People gave, prayed and offered help, and all of this transformed the hurt into a wonderful sense of feeling grateful.

In her diary my mother wrote how dearly they loved me, right from the start. Sure, it was a shock, but they never rejected me, not for a moment. My mother and my father accepted me the way I was and loved me just the way I was.

When my parents told my grandparents, my mother noticed the hurt in my grandmother’s eyes, and tears in my grandfather’s. My granny loved me dearly. I think her love for me was greater than for any other person on earth.

Apparently I was an adorable little baby.

Although Down Syndrome babies usually do not cry a lot, my cries were sometimes heart-rending, especially when my mother was not right on time for the next feeding session. Even at that early stage of my life, food was important to me.

My mother was fortunate enough to have been able to breastfeed me for more than a year.

My weight gain was satisfactory, but I was quite small. My head, which measured 32 cm at birth, quickly grew to 37 cm. My length was also close to that of normal babies. It did not take long before I was less floppy, and I started responding with my eyes quite soon after birth.

My disability led to a couple of funny situations. A very dear friend of my dad kept confusing mongols with morons, who are much dumber than we are! When I was born, the terms “mongol” and “mongolism” were still used. These terms have since become unacceptable, because it’s believed that the words created a negative impression of people with Down Syndrome.

Once, my mother had to explain to an acquaintance that she could not attend a kitchen tea because I had arrived earlier than my due date. When the woman enquired whether everything was okay, my mother told her that there were some problems. The woman then pointed out that medical science had progressed so rapidly that there was no need for my mother to worry; she should have just been relieved that the baby wasn’t a little mongol!

The world does not change when your life changes, my mother always says. The sun still rises, cars still drive around. Nothing changes, even though everything in your life has changed.

Our stay in hospital was fine, even though I developed jaundice. My blood count was the highest of all the babies. At first my mother was proud of my high count, until she learned that it actually wasn’t good at all; it only meant that I was sicker than the other babies!

When we were discharged, a feast awaited us at home. My dad saw to that.

He decorated the entrance hall and organised a picnic, because he thought that we had to start our life as a family with a picnic in our home. I was put down on a blanket next to him and my mother; I had to become used to having picnics.

Our neighbour at that stage, Marlene Sonnekus, gave birth to a little boy ten days after I was born.

My mother told me it was wonderful to watch him develop. He was, of course, much stronger than I was, and he started smiling earlier. Early on, my mother could see when I liked something, but there was still no first smile.

One Sunday evening, when I was about eleven-and-a-half-weeks old, my mother was struggling to help me get rid of nasty winds. But I was very restless and she felt quite helpless.

My father had been to church. My mother knew he’d be able to get me to settle down once he returned. Then, just as she put me down to change my nappy, she very clearly saw a smile, with two beautiful dimples. She could not believe her eyes. And then she noticed that my father had just entered the room. I smiled because I was so glad to see him! From then on I laughed regularly.