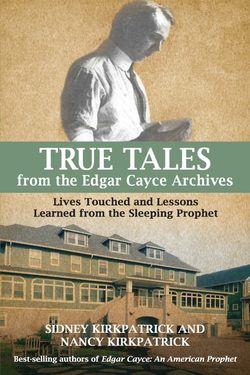

Читать книгу True Tales from the Edgar Cayce Archives - Sidney D. Kirkpatrick - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE YOUNG LADY FROM THE HILL

ОглавлениеEdgar was working at Hopper Brothers Bookstore when he met his former Beverly school teacher Ethel Duke. She recognized him immediately, and after they got to talking, she invited him to a party. It was to be hosted by her cousins, the Salters of Hopkinsville, who routinely held “moonlights” in which their grand antebellum home, known throughout Hopkinsville as “The Hill,” was lit with colorful Chinese lanterns. Guests, mostly young people and students from Hopkinsville’s South Kentucky College, would stroll about the property under the moonlight and stars.

Excited as Edgar was to attend, he was also worried. As he later admitted, he thought the guests would find him “uncouth and uneducated.” The decision, however, was out of his hands. Leslie forbade him to visit the Salter home, if only because its occupants were known liberals. They openly espoused such radical notions as a woman’s right to vote and hold public office. Everyone in Hopkinsville had heard at least one story of how the three older Salter sisters—Elizabeth, Kate, and Caroline—virtually ran “The Hill” and how their dinner guests included Jews, blacks, Hindus, and Native Americans. Leslie may have suspected that all kinds of “subversive” things occurred at The Hill and wanted Edgar to have no part of it.

Edgar abided by his father’s decision. However, this didn’t keep him from finding out more about life at The Hill from his employer Harry Hopper’s girlfriend. Mary Greene, a teacher from South Kentucky College, knew the Salters well and had attended many a moonlight. Among other intriguing things she had to tell him were stories of the family patriarch, seventy-three-year-old Sam Salter, a respected civil engineer, architect, and non-practicing physician from Philadelphia. Since coming to Hopkinsville, he had overseen the construction of the city’s largest building projects, such as South Kentucky College and the Western Kentucky Lunatic Asylum and later became that hospital’s chief building superintendent. He was the radical thinker who set the tone at The Hill. But it was the Salter girls who were in charge. In addition to adding to the family’s extensive personal library and growing their own crops, medicinal herbs, and livestock, all of the Salter children and grandchildren were sent to college, studied foreign languages and music, and were taught the business and professional skills to carry the Salter legacy into the future.

Elizabeth, or Lizzie, the eldest Salter girl, was extremely bright and well read. She married Sam Evans, the owner of the Hopkinsville coal yard and eventually had three children: Hugh, Lynn, and Gertrude, the youngest. The children were still infants when their father died suddenly from a burst appendix, and Lizzie had used the income from selling the coal yard to build a cottage immediately adjacent to The Hill. Though they lived next door, everyone dined together in the larger house and pitched in with chores.

Kate Salter Smith, the next in line, was a gifted musician and could be counted on to entertain at the piano or read poetry. She was also quite the reader, kept up the family library, and was active in theatrical performances at her church. Also thanks to her, the family moonlights included such guests as visiting pastors and distinguished lecturers and musicians who came to speak or perform at the Union Tabernacle or Holland’s Opera House.

Caroline, known as Carrie, was the youngest and most beautiful. A buyer for Anderson’s Department Store, who volunteered part-time as an art teacher at the Hopkinsville asylum, she was not as outspoken as Lizzie and could not write poetry or play music as well as Kate, but she had inherited the full range of Sam Salter’s talents and his fierce sense of independence. Edgar knew Carrie and some of her young cousins because they frequently stopped at the bookstore for college supplies.

The more Edgar learned about the family, the more he regretted not taking Ethel Duke up on her invitation. Thus, when she stepped into the store the following month and issued a second invitation to attend a party at The Hill, Edgar immediately agreed. On this occasion he also caught a glimpse of Ethel’s best friend and second cousin, Gertrude, who sat in a carriage outside. Few words were exchanged that day, but Edgar had the distinct impression that Gertrude, the petite brunette in the back of the buggy, and not Ethel, was issuing the second invitation and was perhaps responsible for the first. His suspicions were confirmed when, disregarding his father’s edict, Edgar polished his shoes, oiled his hair, and attended the party the following Friday at The Hill.

While making bookstore deliveries, Edgar had been inside several of Hopkinsville’s finest homes. They had been built by the wealthy tobacco planters and traders. These homes were more grand and imposing, had more land, and were more conveniently located near the city center. The Hill, however, built by Sam Salter himself, impressed him more than any other. Inside, Edgar was confronted by a rainbow of colors. There were deep purples and blues in the oriental carpets and Chinese porcelains, gold leaf on the picture frames, flaming red window sashes, and velvety greens and browns in the brocade upholstery. But what most captured his attention was the scent of perfume: lavender, primrose, chamomile, and honeysuckle. For a country farm boy, who had grown up in a cabin with a dirt floor, stepping into The Hill was like entering a new, exciting, and distinctly female environment.

Ethel Duke took him by the hand and introduced him to the grey-haired Sam and his wife Sarah, and then to the ladies who ruled The Hill.

Thirty-five-year-old Lizzie, Gertrude’s mother, was as petite and dark-haired as her daughter. She supervised the planting and harvesting of the vegetable gardens and the orchard in addition to seeing that the home was always full of flowers and color. She was also chiefly responsible for The Hill being a forum for political discussion. Elected or aspiring policy makers were always welcome at her frequent salons and dinner parties.

Edgar Cayce, c. 1890s.

Then there was Kate, a fat-cheeked woman with fine hands. He recognized her from Hopper Brothers, and her contribution to the house was everywhere evident in the library, where could also be found the piano which she played so well.

Twenty-year-old Carrie was surrounded by adoring young male suitors. That she hadn’t yet married, Edgar quickly realized, wasn’t for lack of proposals. She simply had hadn’t found the right man and wasn’t willing to settle for second best because she was no longer a teenager. She, too, was a striking contrast to Edgar’s own familiar experience where a woman wasn’t welcome to express an opinion of her own, freely mingle with unmarried men, or use perfume.

Mingling, as Edgar soon realized, was what the moonlight was about. In a matter of minutes he was introduced to clergymen from the Methodist church, railroad engineers, and practically the entire junior class from South Kentucky College. He couldn’t easily enter into the conversation, but he was a good listener, and Ethel Duke filled in gaps in their conversation. All too soon, though, she disappeared, leaving him on the lawn in front of a table with small sandwiches, cookies, and a punchbowl of lemonade. Young people sat on benches and chairs or lay on the ground looking up at the moon. Almost miraculously, Edgar found himself face to face with Gertrude, who took his hand and led him down the carriage path to see her rose garden.

Edgar couldn’t take his eyes off of her. Fifteen-years-old, standing just five-feet tall and weighing eighty pounds, she had silky brunette hair, large brown eyes, an oval face, porcelain white skin with fine, delicate features. This evening she wore an embroidered ankle-length gingham dress that her aunt Carrie had purchased in Springfield for her. “A mere slip of girl” was the way Edgar described her. “Petite, win-some, and graceful” another would say.

How much time Edgar spent inspecting Gertrude’s rose garden, or the full moon overhead, is anyone’s guess. However, in the years to come, he always associated her beauty with roses. He brought her a rose when they later went out on dates and would never plant a garden in any of the homes they lived that didn’t feature at least one rose bush which was produced from stock originating from Gertrude’s plot at The Hill. Today at the A.R.E.’s Virginia Beach headquarters roses from this same stock still grow.

To Edgar’s relief, Gertrude did the lion’s share of talking that night. A romantic, she encouraged him to listen to the sound of tree limbs swaying in the wind. “The souls of lovers, who were cruelly parted,” she is reported to have told him. Eventually she got him to talk about himself and flattered him by suggesting that he was probably so good as a clerk that he would someday own a bookstore himself. A great reader herself, she knew the Hopper Brothers’ inventory nearly as well as he. Clergyman and fiction writer E.P. Roe was her particularly favorite author, something Edgar would note on her next birthday.

Edgar left The Hill that night convinced of two things: that she was most certainly behind Ethel Duke’s invitation and that she knew considerably more about him than he did her. This, too, would soon be confirmed. Thanks to Ethel Duke, who had been a substitute teacher at the Beverly School, and Gertrude’s aunt Carrie, who knew Edgar’s sister Anne from Anderson’s Department Store, Gertrude had been told all about the stories of his ghostly encounters and strange abilities. That Gertrude knew this in advance and was still interested in pursuing a relationship made him all the more enamored of her.

With a chaperone on a date to Pilot Rock, Gertrude is at far right, c. 1902.

No sooner had Edgar attended the party at The Hill than he received numerous other invitations to parties and social gatherings which, by no coincidence, Gertrude was also invited. Still, he remained painfully shy around her, mostly because he couldn’t fathom why a beautiful young woman like Gertrude, from a well-off and well-educated family such as hers, could be interested in a mere bookstore clerk with an eighth-grade education. He wasn’t certain she actually liked him until he accompanied her and Ethel Duke on a picnic to Pilot Rock, a massive limestone outcropping nestled into the Christian County foothills.

They set out from Hopkinsville by wagon with baskets of fried chicken, beaten biscuits, fresh tomatoes, and cake. Outside of town they parked at the foot of the towering rock formation and made the rest of the journey up Pilot Rock on foot. As was customary on this day, and on the many dates they would have in the future, they were accompanied by a chaperone. Their Pilot Rock picnic was followed by a more adventurous trip to a mineral spring (boys and girls bathed separately) and then an exploration, by lantern light, of an abandoned mine.

Edgar and Gertrude soon became a couple, joining one another at parties, church socials, presentations at the Union Tabernacle, and shows at Holland’s Opera House. Both greatly enjoyed sitting in the bleachers whenever the Hopkinsville Moguls took the baseball field. Gertrude’s brother, Lynn Evans, played shortstop. Sunday mornings were devoted to church—Edgar attending the Christian Church and Gertrude the Methodist Church. Afterwards, Edgar would ride his bicycle to The Hill, and they would sit together on the large veranda or in the parlor playing games or reading out loud from books that he had brought from Hopper Brothers.

As a future in-law would later write, theirs was an appeal of opposites. “He [was] excitable, earnest, born of extremes, a social outsider; and she—calm inquisitive, practical, an embodiment of southern gentility. He became charismatic and extroverted [as their relationship developed]; she kept her own counsel. Their immediate rapport held their relationship intact through one crisis after another.”

The first crisis was the disapproval of the senior Salters. Edgar wasn’t educated, had no refinement, and most important couldn’t raise a family working as a bookstore clerk. Even when, several months into the courtship, Edgar received a substantial raise at the bookstore, he was still having difficulty supporting his parents. Leslie hadn’t yet found a job, and Edgar’s mother earned money taking in laundry and working as a seamstress. His sisters helped out as well, but Edgar was the primary breadwinner.

The younger Salter generation—Ethel, Hugh, Lynn, and others—however, embraced Edgar as a brother. They truly enjoyed his company as he did theirs. Hugh and Lynn also engaged him in ways that few others dared. They challenged him to psychically read a deck of playing cards face down (which he did without apparent difficulty). They also tested his uncanny ability to find lost objects (which he invariably was able to do) and to read unopened letters. To them, he wasn’t a freak, but a wonder to behold.

Edgar and Gertrude at the house known as The Hill, c. 1902.

Gertrude’s aunt Carrie wasn’t interested in these activities, but she, too, appreciated his unique abilities. She was more fascinated by his experience with the angel, and how, when praying, he sometimes heard heavenly music. Feeling secure in her company, he shared aspects of himself he had kept hidden. Among other things, he revealed that he could sometimes see colors or patterns of colors around people when the person was feeling strong emotions.

Gertrude didn’t embrace this part of Edgar’s life. Concerned, she discussed the matter with one of her college professors. He told her in no uncertain terms that Edgar would become mentally unstable if he continued to experiment and indulge in psychic-related activities. Likely he would one day have to be committed to the Hopkinsville asylum. This was a particularly difficult thing for Gertrude to put out of her mind. She had only to step out on the veranda of her house to see the asylum’s spires, built by her grandfather, on the horizon. They became a constant reminder of what might be. Unable to remain silent on the matter, she finally discussed the subject with Edgar. He told her the truth. He didn’t like or understand the strange abilities he seemed to possess and wanted nothing more than to live a normal life. He also promised not to engage in further experimentation.

Two incidents, however, left Gertrude frightened. One Sunday evening, when Edgar was nodding off on the sofa in the family’s parlor, Gertrude told him to “go to sleep.” Edgar immediately went to sleep and couldn’t be woken up that night or the following morning and afternoon. Not until a frantic and frightened Gertrude shouted, “Edgar, wake up!” did he instantly open his eyes, acting as if minutes, not an entire day, had passed. Somehow or another, Edgar’s unconscious self had responded to her words as a command. It was as if her voice had a hypnotic effect upon him.

Another curious incident took place at the Cayce’s home on Seventh Street. On a particularly cold winter night, Edgar and a friend from out of town were returning from a revival meeting at the Tabernacle. The plan was for his friend to spend the night with Edgar in his bedroom. But when they walked into the Cayce house, they were surprised that extended family had unexpectedly dropped in from Beverly. Leslie had requisitioned Edgar’s bedroom, and there was no place for him or his friend to sleep. Edgar was steaming mad. This was his bedroom. Further, he was paying the rent on the house. While Edgar and his father exchanged angry words, Edgar’s friend bid a hasty retreat.

Edgar, fully dressed, went to sleep on the sofa in the living room. As he later told the story, which was corroborated by family members, at some point after everyone had gone to bed, the sofa upon which Edgar slept burst into flames. He ran outside and rolled in the snow, putting out his burning clothes. By this time everyone else in the house had awakened and helped to haul the burning sofa out the front door as well. As Edgar had not been smoking, the lamps were extinguished, and the sofa had not been near the stove, the cause of the fire remained a mystery. However, evidence suggested that the fire had started in Edgar’s clothes before spreading to the sofa and that somehow or another, the incident was directly connected with Edgar’s state of mind.

But as he and the Cayce family, and Gertrude too, would one day experience when they entered the photography business, fires had a strange way of igniting under unusual circumstances when Edgar was angry. Two of Cayce’s four photo studios would burn down, and a third suffered serious fire damage. In later years, special efforts would be made to fireproof the various storerooms which housed the Cayce trance readings.

The impact that such incidents had on Gertrude were more profound than commonly thought. She would be the last of her family members to receive or witness a trance reading. For the first eighteen months of their courtship and for years to come, she and Edgar would not talk about or discuss anything related to his psychic gifts. This was how she wanted it, and it may have been a condition when Edgar, on March 7, 1897, days before his twentieth birthday, proposed to seventeen-year-old Gertrude.

“It’s true that I love you,” she told him. “But I will have to think about it.”

Edgar naturally wanted to know when he would have an answer, and a part of him still believed she wouldn’t accept his proposal. There were times when Gertrude looked at him, he said, as if he were “a strange fish that ought to be thrown back.”

Perhaps, even in their relative youth, both suspected that theirs would never be a normal life together. They would never simply be Edgar and Gertrude. There would always be a third unseen “other,” what in years to come would simply be called “the Source.” It seemed at times to threaten to end their relationship and as events would unfold, was ultimately what held them together.

On the evening Edgar proposed to her, however, Gertrude was holding her ground for a different reason. One of her aunts had counseled reserve in matters of the heart. She shouldn’t seem too eager. Gertrude went to a calendar in the parlor, closed her eyes, and put her finger on a date. “I’ll tell you on the twelfth.”

Five days later, in a driving rain, Edgar arrived back at The Hill on horseback. Gertrude, after giving the matter consideration, said she would marry him. As Edgar later related the story, he didn’t know what to do next. She was standing in front of him, waiting for him to kiss her. When she asked him why he hesitated, he explained that he had never kissed a woman before. Gertrude showed him how.

The matter of how her voice, in particular, had a profound effect upon him, and other psychic matters, was forgotten for the moment. Like her, he envisioned a day, not long in the future, in which he and she would stroll through the park on a Sunday afternoon, taking turns pushing a stroller, and greeting friends they met along the way. He believed, if he tried hard enough, he could put the strange incidents of his past behind him.

Gertrude and Edgar portrait, c. 1903.