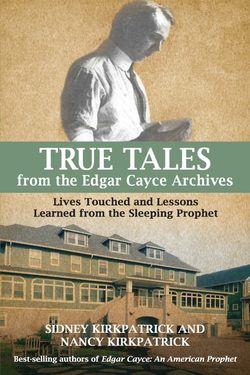

Читать книгу True Tales from the Edgar Cayce Archives - Sidney D. Kirkpatrick - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCING THE PSYCHIC DIAGNOSTICIAN

ОглавлениеHypnosis is widely regarded as an effective therapeutic technique to relieve pain, overcome bad habits, and recall past events. Less understood is its ability to enhance psychic ability. People who are hypnotized routinely perform better in laboratory tests of clairvoyance, telepathy, and precognition. This was the case for twenty-four-year-old Cayce who, with the help of self-taught hypnotist and osteopath Al Layne, produced his first trance reading on March 31, 1901.

Putting Edgar into trance was more difficult than one might suppose for a young man who had already displayed a wide range of other talents. The first attempt to hypnotize him was made by Stanley “The Laugh King” Hart, who invited Edgar onto center stage at Holland’s Opera House shortly after Edgar and his family had moved to Hopkinsville. Although Hart was an ardent spokesman for the alleged powers of hypnotism to cure headaches, treat alcoholism, and eliminate self-destructive behaviors, it was comedy that drew crowds to his performances. He invited members of the audience onto the stage, put them into a hypnotic trance, and ordered them to do embarrassing things. Hart swore just by looking at Edgar that he would make the ideal hypnotic subject, but to everyone’s disappointment, Hart was unable to put Edgar into a trance, and he was asked to leave the stage.

Four years later “Herman the Great” made a second attempt. While visiting the Louisville printing company where Edgar was then working as a clerk—Edgar needed a greater income if he was to marry Gertrude and raise a family—Herman declared the young man would make an ideal subject for hypnotism and asked permission to put him “under.” Edgar agreed to be hypnotized but advised Herman of the previous attempt. The hypnotist was not put off. He told Edgar that the more often a person was hypnotized, the easier it was to put him under, and the deeper he could go.

Hart the Laugh King’s Newspaper Ad, c. 1899.

Holland’s Opera House.

Herman had Edgar concentrate on some object that was held up in front of him while Herman repeatedly made suggestions that he relax and go to sleep. The next thing Edgar remembered was that he was lying on a countertop surrounded by co-workers. He had not only gone under but had done everything that the hypnotist told him to do. Edgar laughed about the experience and promptly forgot about it until a year later when he was hypnotized in Madisonville, Kentucky, while on a business trip with his father, Leslie.

Edgar and Leslie had been in Madisonville only a few hours when state health officials arrived at their hotel and ordered its doors closed. The hotel was being quarantined due to an outbreak of smallpox. No one could come or go for three days. By coincidence, a fellow guest at the hotel was a stage hypnotist who volunteered to provide entertainment.

Like Herman the Great, the hypnotist succeeded in putting Edgar into a trance. Again, Edgar had no memory of what happened because he lost consciousness the moment the hypnotist put him “under.” Edgar knew only what Leslie and the other hotel guests told him when he woke up. According to them, the hypnotist suggested that Edgar play the piano.

Leslie had expected Edgar to simply bang away at the keys like a child pretending to make music. After all, he had never had a single lesson. Only Edgar took the hypnotist’s suggestion literally, exhibiting a skill far beyond what even the hypnotist believed possible. Edgar played beautiful music. The hypnotist, no doubt, believed that he had helped Edgar to discover a latent ability. The truth, however, was more astonishing. Edgar was capable of doing extraordinary things when under trance—the likes of which no one could have imagined.

The incident which led to Al Layne’s entry into the story came in the winter of 1900 when Edgar, on a business trip to Elkton, Kentucky, was prescribed too strong a sedative to treat a migraine headache. Several hours after taking the drug, Edgar was found wandering semi-conscious in the Elkton railroad yard and was brought home to Hopkinsville. Physicians didn’t know how to help, so they put him to bed. He seemed to be fine the next morning. The only problem was that his throat was dry and scratchy, and his voice thin and raspy.

Days passed, then weeks, and eventually months, and his condition became more severe. Unable to communicate, Edgar lost his job as a salesman. Eventually he took a position, arranged for by friends, working in a darkroom in a Hopkinsville photo lab. It would be here where he learned the trade that would lead him to become a professional studio photographer. Here, too, he bemoaned the fact that he was now unsuitable to be a husband and father. In a moment of self-loathing and pity, he begged Gertrude to release him from what had now become their year-long engagement. She deserved more from a potential husband than he could deliver. Gertrude would hear none of it.

After nearly a full year without any improvement, everyone in Hopkinsville knew about Edgar’s condition. Friends urged him to pay a return visit to Stanley Hart, who was scheduled to appear at Holland’s Opera House. Hart was certain he could affect a cure and was undoubtedly pleased at the prospect of proving himself in front of a paying audience.

Edgar, thin as a rail after a year of laryngitis.

On the night of his performance, Hart invited Edgar onto the stage. When the oil burning footlights were dimmed, Hart stood directly in front of Edgar and told him to concentrate on an object which he dangled in front of Edgar’s eyes. Edgar slipped easily into a trance.

No record exists of what words Edgar spoke, only that he did. His laryngitis was gone. The audience gasped, then began to cheer wildly. Hart had performed his magic.

Or had he? Once Edgar was released from Hart’s hypnotic suggestion, his voice once again became a whisper.

After the show had ended, Hart took Edgar and Gertrude backstage and explained the problem. Edgar could not go deep enough into a trance to take “post-hypnotic suggestions.” More trance sessions would be necessary.

Assured that he could affect a permanent cure, Hart promised that for $200 he would keep trying until Edgar had completely regained his voice. Edgar and his parents, and likely Gertrude, too, agreed to the arrangement even though they hadn’t the money to pay his exorbitant fee. The problem was apparently solved when the editors of the Kentucky New Era newspaper stepped forward. They met with Hart and a Hopkinsville throat specialist who agreed to examine Cayce both before and after the hypnotic sessions. In return for an exclusive, they would see that Hart was adequately compensated.

The sessions did not go as expected. Hart could easily put Edgar into a trance, but the moment Edgar was commanded to wake up, he lost his voice again. Given future events, it is reasonable to conclude that Hart’s appraisal of Edgar’s condition was correct. Edgar’s laryngitis was psychosomatic, a condition which could be helped with hypnosis. However, his condition was also partly physiological. His vocal chords were constricted when he was in a waking state. This was perhaps because Edgar, in a waking state, was trying so hard to suppress his psychic gifts. With his desire to please Gertrude, earn a better income, and lead a normal life, he had strayed far from the promise he had made to the angel of his youth. The “voice” within him was trying to be heard, and the only way to suppress it was to constrict his vocal chords. This condition, too, may also have been treated with hypnosis, but Hart didn’t know how to put the correct suggestion to Edgar when he was under. When hypnotized, Edgar had powers over his own body that were far beyond what Hart, or anyone else, could imagine.

Hart gave up on Edgar. But others took up where he left off. College professor William Girao, who had been in the audience at the Opera House, wrote to John Quackenboss in New York, who was considered one of the foremost experts in hypnotism. The fact that he was also an ardent believer that illness could be healed by a person learning to marshal the forces of the unconscious mind would prove to be most helpful.

Quackenboss took the case on and made repeated visits to Hopkinsville. Before he began his experiments, he questioned Edgar and his parents at length, listened to Leslie’s account of Edgar’s childhood experiences, and took copious notes.

In one experiment, when Edgar was asked to sleep for twenty-four hours, he immediately closed his eyes and went to sleep. Not just this, Edgar appeared to be comatose. He didn’t awaken for twenty-four hours—precisely to the minute. This was a modest breakthrough, as it showed that when Edgar was put into a deep trance, he truly did what was asked of him. However, it didn’t cure his condition.

After Quackenboss gave up, Girao continued to experiment and engaged the help of Al Layne, the only person he knew in Hopkinsville who had training in hypnotism. A delicate middle-aged man with a pencil-thin gray mustache and a prominent bald spot on the top of his head, Layne weighed less than 120 pounds, in contrast to his wife, Ada, a heavy, large-breasted, robust woman. As would soon prove helpful, Layne was predisposed to assist Girao because he knew Edgar personally. Layne’s wife, Ada, employed Edgar’s younger sister Anne Cayce and Gertrude’s aunt Carrie Salter at Anderson’s Department Store.

Though Layne called himself both a hypnotist and physician and operated a small office at the back of Anderson’s Department Store, he had little formal training. The extent of his certification was a correspondence course. Still, he had a modest following of dedicated clients, many of them people such as himself, who suffered stomach ailments and who had found no relief from standard allopathic medicine. Like Professor Girao, he was an ardent believer in a popular slogan of the day, “Every man his own doctor,” and was part of a groundswell of popular interest in what today would be called holistic health. Hypnotism was merely one aspect of a medical treatment that also included osteopathy, the science of manipulating or realigning human vertebrae to permit the body to heal itself, and homeopathy, a treatment based on the use of natural remedies to trigger the body’s own immune response.

Al Layne, taken from a newspaper article, c. 1906.

Al Layne’s newspaper ad, c. 1902.

Edgar, as Layne concluded, was in desperate need of both osteopathy and homeopathy, but it was hypnotism that he and Girao applied first. As in the earlier experimentation with Quackenboss, Edgar went into trance easily and would speak in a normal voice. But as soon as Edgar came out of trance, the laryngitis returned. The only thing new they learned from their efforts was the observation that Edgar was unusually talkative in his trance state. Layne could actually carry on a conversation with him. Edgar would stop talking only when the suggestion was made that he go into a deeper trance, at which point communication would cease altogether.

Layne and Girao put their findings into a letter to Quackenboss. In response, the New York hypnotist said that he had observed a similar tendency when working with Edgar. He noted a particular point in the hypnosis process when Edgar’s unconscious self seemed to “take charge.” An avenue to explore, Quackenboss suggested, was to put Edgar “under” and ask Edgar’s unconscious self what he thought should be done to restore his voice.

Edgar’s parents were reluctant to let their son be hypnotized yet again. He had lost sixty pounds and as Edgar himself admitted, was a “nervous wreck.” Now, along with his Bible, he carried a pencil and pad, which was the only way he could communicate with the outside world.

Gertrude, too, had suffered. Already thin, she now looked anorexic. She had dropped out of college and rarely ventured into public to attend the many social and church gatherings around which her life had previously revolved. She also hadn’t attended Edgar’s hypnotic sessions with Quackenboss, Girao, and Layne. Edgar’s public embarrassment on the Holland’s Opera House stage was humiliation enough.

With Edgar’s blessing, Layne convinced Leslie and Carrie to let him try one more experiment. On Sunday afternoon, March 31, 1901, less than two weeks after his twenty-fourth birthday, he and Layne retreated to the Cayce’s upstairs parlor. Edgar lay down on the family’s horsehair sofa, and Layne pulled up a chair to sit next to him. Edgar’s mother stood alongside Layne. Leslie was seated in a chair across from his son.

Edgar put himself into trance, as he had learned to do from having undergone so many previous experiments. Just as Edgar’s pupils began to dilate and his eyelashes fluttered and when he looked as if he was going “under,” Layne made his first suggestion.

“You are now asleep and will be able to tell us what we want to know,” Layne said. “You have before you the body of Edgar Cayce. Describe his condition and tell us what is wrong.”

Edgar began to mumble, then his throat cleared and he spoke. “Yes,” he said. “We can see the body.”

Layne told Edgar’s father to write down what was being said. Leslie scrambled to do so but was so disconcerted by what was happening to realize that a pad and paper were within easy reach. He instead ran into the kitchen and retrieved the pencil that was tied to the grocery list. Even so, he was too flustered to write anything coherent down on the paper. What Edgar said is today pieced together from the recollections of Edgar’s mother and Layne.

In the normal physical state this body is unable to speak due to partial paralysis of the inferior muscles of the vocal cords, produced by nerve strain. This is a psychological condition producing a physical effect and may be removed by increasing the circulation to the affected parts by suggestion while in this unconscious condition. That is the only thing that will do it.

Layne would note the curious way that Edgar was addressing himself in the third person. He also spoke more slowly than he normally would in a conscious state, enunciating each individual consonant and vowel as if he were translating from some foreign language.

“Increase the circulation to the affected parts,” Layne then commanded.

Edgar replied: “The circulation is beginning to increase. It is increasing.”

Layne leaned over to look at Edgar. Just as the “sleeping” Cayce had said, the circulation to his throat actually appeared to increase. He could see his neck begin swelling with blood to the point that Leslie was compelled to lean over and unbutton his son’s shirt collar. The upper portion of his chest, then throat, slowly turned pink. The pink deepened to become a fire-engine red. A full twenty minutes elapsed before Edgar cleared his throat and spoke again.

“It’s all right now,” Cayce said, still in trance. “The condition is removed. The vocal chords are perfectly normal now. Make the suggestion that the circulation return to normal, and that after that the body awaken.”

Layne did as instructed. “The circulation will return to normal. After that the body will awaken.”

The red around Edgar’s neck faded to rose and then to pink. He woke up a few minutes later, sat up, reached for his handkerchief, coughed, and spat out blood. The blood that came out was not just a drop or two, but enough to soak the thin cotton cloth.

“Hello,” he said, in a clear voice. “Hey, I can talk.”

Edgar’s mother cried with relief. Leslie pumped Layne’s hand. Edgar’s sisters, Anne and Mary, who had been eavesdropping through the keyhole, also found “brother’s experience,” as they called it, “quite exciting!”

Edgar had no memory of the experience. He repeatedly asked to be told every detail of what had happened. What had Layne said? What did I say? How did I look? Unbelievable as the story sounded, his shirt collar was open at his neck, his handkerchief was bloodstained, and he could once again speak in a normal voice.

Layne had conducted Cayce’s first trance reading. He also made the observation which would result in the second. “If you can do this for yourself,” he told Edgar, “I don’t see any reason you can’t do it for others.”

With his voice restored, Edgar and Gertrude finally set their wedding date!

Edgar and Gertrude married on June 17th, 1903.