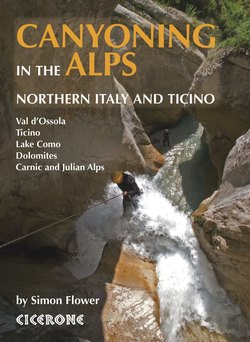

Читать книгу Canyoning in the Alps - Simon Flower - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

No room for error – a technical 100m pitch in Sponde (Route 18 in the Ticino region)

Frequently hidden among a backdrop of lofty mountain peaks, the canyons of the Alps are wild and forbidding natural reserves, where rivers, waterfalls and clear-green pools nestle between towering walls of rock and vegetation. They are the awesome product of tremendous erosive forces, scored deeply into rock over millennia by the movement and melting of glaciers that have long since disappeared.

Unlike the mountains around them, with their bold, universal appeal, the canyons attract a more select crowd, prepared to tackle a unique variety of hazards and challenges. Certainly, mountaineering ability will be called upon, but the fast-flowing alpine streams demand additional skills more familiar to white-water enthusiasts. At times the current can be an intimidating barrier to descent. Very often abseils are under the full flow of water or into plunge-pools seething with waves and undercurrents. Many waterfalls must be (or at least should be) jumped or tobogganed. Some control has to be abandoned to the river – a concept not everybody will be comfortable with. This makes canyoning in the Alps a serious mountain sport, but one punctuated by moments of child-like thrills.

In this book you will find some of the best descents that the Alps (and the sport) have to offer. Many are long, technical and aquatic in nature, geared towards physically fit parties unfazed by white water, rope work and hard labour. While previous canyoning experience isn’t necessary, a background in other mountain sports (such as mountaineering, caving or climbing) is. A number of canyons are suited to people who have never canyoned before, provided they are in the company of more experienced team mates. It is fundamental that you develop your understanding of canyoning hazards and safety and its special descent techniques with experienced canyoners.

The canyons are grouped into five Italian-speaking areas across northern Italy and Switzerland, outlined below. Sitting at their peripheries are the best canyons of Slovenia, Austria and the Valais Alps, which have been included as a bonus. Most are within easy reach of a single base (usually under an hour’s drive), making each area a perfect destination for a week or fortnight’s canyoning holiday. The book also contains practical information needed for organising your stay, including details of walking, climbing and via ferrata possibilities in each area (this is the Alps, after all). Finally, as this sport remains so little known in the UK, some advice regarding the precautions, equipment and techniques specific to the sport is also given.

The 45m pitch of Lodrino Inferiore (Route 33 in the Ticino region)

Val d’Ossola

An area of wild alpine rivers carved into the gneiss and granite peaks west of Lake Maggiore, this region spans from the rugged terrain of Val Grande National Park to the towering giants along the Swiss border. Two canyons in the Swiss Valais region are also included.

Ticino

Switzerland’s sunniest canton is a canyoner’s paradise, famous for its lofty, theme-park-like canyons. The canyoning is only a stone’s throw east from Val d’Ossola, in two broad valleys snaking north from Lake Maggiore. With the canyons so closely huddled together, Ticino probably has the greatest concentration of superb descents anywhere in Europe.

High water levels in Grigno (Route 54) meant that it was several years before the first successful full descent was made

Lake Como

The area around Lake Como offers a mishmash of different mountain ranges and canyoning styles. It encompasses the mighty Bernina and Lepontine Alps on the Swiss border, along with the Orobie Alps and limestone pre-Alps further south. Their differing geology affords the canyons very different characters, ranging from beautiful gneiss playgrounds and sunlit granite cascades to cave-like limestone and serpentinite tombs almost totally devoid of light.

The Belluno and Friuli Dolomites

These wild mountains fall largely within the national and regional parks around Belluno, on the quiet south-eastern edge of an otherwise busy mountain range. The unique, rugged Dolomite terrain is reproduced in the canyons here, which are frequently long, remote and technical in nature.

Carnia and the Julian Alps

The little-visited limestone mountains of north-east Italy offer an excellent introduction to alpine canyoning. The canyons are scattered throughout the Carnic Alps, the Julian Alps and the pre-Alps to the south, with a handful over the borders with Austria and Slovenia. Aside from one or two notable exceptions, their canyons remain within the reach of most cavers and climbers.

Canyoning – a brief history

The beginnings

Canyoning in its modern guise is a relatively recent sport, but its origins can be traced back a century or more to the exploits of a handful of French cavers and explorers. Armand Janet is usually credited with the first technical descent. In 1893 he made a partial descent of the Gorges d’Artuby, a tributary of the Verdon, armed with only a rope and a few planks of wood. In 1905 an expedition led by Édouard Alfred Martel, a man widely regarded as the father of modern speleology (caving), set off in boats to explore the Verdon Gorge itself. At over 20km long and up to 700m deep, it was a serious prospect, with few possibilities for escape or retreat. Janet, who was on his team, had already made an attempt on the gorge nine years earlier but had been pushed back by the Verdon’s considerable current, which was then many times what it is today. The current caused problems for Martel’s team too:

So formidable was this passage that, in fact, we can barely remember anything at all, too preoccupied with paddling the boats clear of rocks. The boulders create three crevasses of furious water, passed quickly and without injury. The boats are all but thrown ashore, where our assistants have just arrived, stunned by our audacity…and our luck. One boat is broken up somewhat.

We are at the bottom of a veritable well; our outstretched arms can almost touch the walls, which loom 400m overhead, shielding us from the sky. Up above the sun is shining; down here, in this aquatic dungeon, it is nearly night; an awesome, unimaginable spectacle.

…More than once the ropes are required to avoid slipping into a water hole, where we would certainly be crushed. At least the splendour of the canyon is unrivalled. But the more it widens, the more the boulders block our way. We must clamber out, boats on our back, to gain a sort of ‘track’ 100m above the river. The going is terrible, virtually a virgin forest, but it seems excellent in comparison to the rocks below.

De Joly clad ready for the Imbut (photo from Memoirs of a Speleologist, Robert de Joly (1975))

Several of the men gave up on the third day, tired and demoralised. The remainder of the team, which included Martel and Janet, arrived exhausted at the ‘Pas de Galetas’ on the fourth day, successfully completing the first descent of the gorge. Only the semi-subterranean passage of the Imbut remained unexplored. Here, for 150m, the raging Verdon waters burrow through the base of the limestone cliffs rather than take a surface route. The passage was dismissed by Martel as too risky a venture; he opted instead to carry boats and equipment along the dry river bed. It was another 23 years before Robert de Joly, Martel’s friend and disciple, returned to investigate.

Wearing a flotation jacket and lead weights around his ankles to keep him upright, he took to the water:

I entered the water and was carried along swiftly. Before long I was in a calm, level passage, surrounded and boxed in on all sides by the mountain. The roof was at least 36 feet high, and the channel width varied from two to five yards.

All of a sudden a kind of wall came into view. Did this mean there was no way out, that the water exited through a siphon? I was seized by fear. It was absolutely impossible to fight back against the current. Should I have heeded the wise, reasonable counsel of my companions instead of throwing myself into such a risky adventure?

Very probably, but he was hauled to safety, lead weights and all, by his team mates as he eventually emerged on the far side.

A ground-breaking descent

In 1906 Martel made the first descent of the Daluis Gorge before making an aborted attempt on Clue d’Aiglun, an imposing and aquatic cleft in the Maritime Alps. In the following year he turned his attention to the Basque Pyrenees, focusing much of his efforts on the imposing Canyon d’Olhadubie. Even by modern standards the Olhadubie retains an air of seriousness, and despite a series of expeditions probing its upper and lower reaches nearly a mile remained unexplored by the time Martel departed from the scene in 1909. Interest in the gorge dwindled until nearly two decades later, when the rising popularity of caving and climbing produced a string of new challengers.

In 1933 the canyon finally fell to Henri Dubosc and a group of active young mountaineers from Pau – Roger Ollivier, Francois Cazalet and Roger Mailly, men who later became household names in Pyrenean climbing history. Ditching hobnailed boots in favour of flimsy fabric plimsolls and clad in just swimwear and a couple of woollen sweaters, they made a full descent of the gorge in just over 13 hours. They opted for a lightweight, alpine-style approach, employing ropes and a pull-through technique rather than the heavy rope ladders of old. It was a landmark in canyon exploration, and was described by Ollivier in his report:

Our equipment, as picturesque as it is rudimentary, throws a note of gaiety into the expedition. No hobnailed boots this time, not even stockings or socks, but simple esparadilles [Pyrenean plimsolls], swim wear, two big pullovers and a pair of old trousers to reduce rope friction. Dubosc sports a pair of amusing red flannel culottes and a curious white hat.

A sling is placed around an enormous block, a 50m rope uncoiled and Dubosc, protected by a life-line, confronts the first cataract. The water pummels his head violently, his pretty white hat carried away. Our companion finally reaches a sort of cauldron, seething with worrying eddies. But he’s landed in water only shoulder-deep. We hurl the sacks unceremoniously down the pitch. The first, which lands with a resounding ‘plouf’, is greeted with a great burst of laughter from Dubosc, who wades off with fervour. I descend last, pull the rope through and rejoin my companions. All retreat is now cut off from above.

The golden years of exploration

Over the next couple of decades exploration quietly continued, but was severely impaired by a lack of suitable equipment and clothing. Although climbing hardware became more sophisticated with each year, protection against the icy waters remained limited until the appearance of neoprene wetsuits in the mid-1960s. With these modern materials the 60s and 70s were a boom-time for canyon exploration, and with vertical caving techniques becoming more widely used caving clubs again led the way. The Sierra de Guara in northern Spain became a hive of activity, culminating in 1981 in the first true canyoning guidebook (Les Canyons de la Sierra de Guara by Jean-Paul Pontroué and Michel Ambit). The book helped popularise the sport among the wider public and ensured an explosion of interest throughout France, Spain and then Italy. By the beginning of the 90s, most canyoning areas of France and Spain were represented by topo-guides, along with a handful of areas along the length of Italy.

The appearance of relatively light and affordable masonry drills during the 1990s meant that more ambitious projects became possible in the harder rock types of the high Alps. A new breed of explorer came to the fore, many of them alpinists and mountain guides willing to push the boundaries. During this time the grand classics of Val d’Ossola, Ticino and Lake Como were opened up, although, as in previous decades, the exact details of exploration remain scanty. Lake Como’s history is perhaps the best documented, owing to Pascal van Duin’s seminal guidebook Canyoning in Lombardia. Van Duin himself has been one of the most prolific modern explorers, as a glance through the list of first descents in Appendix F will testify.

The rising popularity of the sport paved the way for professional canyoning outfits, which could cash in on the improved safety margins of sturdier rigging. Even so, a number of companies had questionable standards and poor safety records. In 1999 the sport gained notoriety following the tragic deaths of 18 paying tourists (mainly Australian) and three guides during a flood-pulse in Saxetenbach Gorge, near Interlaken.

Val Zemola (Route 66 in the Friuli Dolomites), one of Italy’s most famous canyons, was first descended in 1986

The present day

Canyoning ethos in western Europe has shifted firmly from exploration to sport. Certainly, in France and Spain it seems unlikely that any great surprises lie in wait. Both countries have been thoroughly scoured for canyons and the more notable finds published in guidebooks or websites. Elsewhere, canyon details have taken longer to filter through to the wider canyoning community – northern Italy was virtually terra incognita until the first guidebooks emerged at the turn of the 21st century, and central Switzerland appeared on the map only in the last couple of years.

Undoubtedly, there is still more to be found. Of the areas in this guide, Carnia and the Julian Alps hold perhaps the greatest potential, yielding three classic descents during the time this book was written.

Outside Europe, away from the US, Australia and the French and Spanish overseas territories, there is enormous opportunity for making first descents. There are few places on the Earth’s surface that remain as little known as canyons. Even in New Zealand, with its thriving outdoor community and majestic, canyon-rich mountain scenery, the sport has only just taken off. Travel to Asia, South America or almost any other mountainous land you can think of and the canyons are there for the taking. Pack your flags and get out there!

Geology of the Alps (for canyoners)

A brief history of the Alps

The Alps, like all great mountain ranges, were created by the collision of continents. They began rising some 90 million yeas ago as Italy, inching slowly northwards, collided with the southern edge of mainland Europe. The ocean floor that once divided the two continents gradually disappeared, driven into the Earth’s mantle as the gap between them closed. As the land masses collided, their margins buckled, folded and slid over each other to form immense overlapping thrust sheets, or nappes, which pushed northwards as Italy continued to advance. In this way, great rock masses from the Italian plate were displaced far to the north to create mountains in what are now Switzerland, Austria and France. As the Alps rose, the rocks of the ancient seabed were exhumed, now metamorphosised by the immense heat and pressure of the Earth’s interior. Today these hard-wearing metamorphic rocks (the so-called Penninic nappes) form much of the backbone of the Western Alps.

Beautifully shaped gneiss in Massaschluct (Route 1 in the Valais Alps)

Canyon formation

Although plate tectonics are responsible for the formation of the Alps and the distribution of its rock types, the rugged landscape seen today is largely due to glaciation. Over the last two million years there have been a number of periods of glacial advance and retreat that have done much to remodel the region. The last glacial period ended some 10,000 years ago, when the climate changed so quickly that the glaciers retreated into the mountains over only a few hundred years – a mere blink of an eye in geological terms. Colossal sheets of ice were set in motion across the mountains, scouring deep channels into the rock and forming conduits for billions of tons of melt-water – the canyons we see today.

Limestone environments are susceptible to another, more subtle process – karstification. Limestone is one of the few rocks soluble in rainwater (a weak acid), and it gradually dissolves over time to form a number of characteristic landforms, including caves, dissected plateaus and deep slot canyons.

The regions and their rock types

The canyons of Val d’Ossola, Ticino and the north-western shores of Lake Como are for the most part formed in gneiss, a highly metamorphic rock of the Penninic nappes. At extremes of temperature and pressure within the Earth’s interior, minerals of a similar type within the parent rock (here mainly granite) have migrated and aligned together. This gives the rock a beautiful decorative quality with swirls and bands of different colours, polished smooth by the action of glaciers and flowing water. These canyons are often sporting, with deep green pools and gently sculpted waterfalls ideal for jumps and toboggans.

Impressive limestone scenery in Rio Simon (Route 85 in the Julian Alps)

The area around Lake Como is geologically complex, and gneiss is only one of a number of rock types in the area. Valtellina, a broad valley extending east from the northern tip of the lake, is part of a long fault line – a weak point in the Earth’s crust – that runs east–west across the Alps. The fault, known as the Insubric Line, marks the boundary between the Italian and European plates. This weakness has allowed liquid magma to ascend from beneath, cooling slowly within the Earth’s crust to form coarse-grained rocks such as granite and diorite. These have been exposed in a number of places along the fault, creating some of the youngest mountains in the Alps. Among these is Piz Badile, a granite peak on the Swiss border, where a couple of canyons reside. Although granite is hard it erodes quickly on account of its grainy structure, leaving well-rounded canyons open to sunlight.

Just east of Piz Badile is Piz Bernina, one of the most celebrated mountaineering peaks in the eastern Alps. Its southern slopes are formed of a distinct grouping of rocks that includes basalt, gabbro and serpentinite. These rocky assemblages are common throughout the Alps. Termed ‘ophiolites’ in the early 19th century (a word derived from the Greek for snake-stone), it would be another 100 years before their significance was understood. They are now believed to be fragments of the ancient ocean crust, scraped off as they dipped beneath the advancing Italian plate. Serpentinite, derived from the deepest layer, is the most significant from a canyoner’s perspective. It has a mottled greenish tinge and waxy polished surfaces similar to soapstone (to which it is closely related). Serpentinite canyons are extremely rare. Perhaps the best known is Cormor on the flanks of Piz Bernina, famous for its sculpted cave-like passages, almost totally devoid of light. There is nowhere else in Europe like it.

To the south of the Insubric Line, from Lake Como to Slovenia, lie the Southern Limestone Alps, home to the limestone areas described in this guide. All limestone (and dolomite) in the Alps originated in the ancient seas that once separated Italy and Europe. It is formed from calcium-rich minerals mainly derived from the shells of marine organisms laid down throughout the Mesozoic Era (the ‘Age of the Dinosaurs’ – around 65–250 million years ago). Owing to the solubility of limestone in rainwater, limestone canyons tend to be narrow, twisting and deeply encased, resembling cave passages open to sunlight. Like their subterranean counterparts, karst features such as stalactites, flowstone and rock arches are common. Distinct bands are often visible on the canyon walls, each representing a different age of limestone formation, although the banding is now rarely horizontal owing to folding and buckling of the Earth’s crust. Older layers underlie more recent ones, and a descent through a limestone canyon may take you through several million years of Earth’s history.

Weather and when to go

Water levels in a canyon are a reflection of weather conditions (chiefly rain, snow and temperature) over the preceding weeks to months. Ideally, it would be possible to plan a holiday when water levels are sensible (or not so sensible, depending on your persuasion) during periods of fine, settled weather. Unfortunately, predicting both water levels and the likelihood of having good weather is difficult, as the weather conditions in any given month differ dramatically from one year to the next. For example, a snowy winter or a wet spring will mean water levels remain elevated in summer, even if the summer is hot and stable. In other years, the spring months will be dry and canyoning perfectly feasible. Recommending when to visit is therefore a little tricky, and the advice given here must be taken with a degree of caution.

In general, the summer months (mid-July to mid-September) are the best time for canyoning in the Italian Alps and Ticino. Days are frequently sunny and periods of prolonged rain unusual. August is the hottest month – often rising to 30°C in the middle of the day – and the cool mountain streams make very welcome retreats. However, this is the peak month for Italian tourism – accommodation is expensive and harder to find, and certain canyons can get busy with groups (although this is much less a problem than in southern France or Spain). Afternoon storms, the canyoner’s nemesis, are also a feature of the Alps in the summer months. This is especially true in northern Italy and Ticino, where the warm, moist air of the Mediterranean meets the cool air of the mountains. More than at any other time of year, it is essential to check the weather forecasts (details given in each chapter) and monitor the sky for signs of cloud build-up.

Bouldery going in Massaschluct (Route 1 in the Valais Alps)

As the summer wears on, water levels usually decrease. Days cool off a little and the crowds go home. Good weather can stretch into October, although tourist facilities start to close down. Without the heat, any rain that falls tends to augment the rivers for much longer, and on the higher slopes it may fall as snow. Although certain canyons may remain feasible into autumn, canyoning in winter conditions is an entirely different sport. Rivers freeze over and narrow passages become choked with snow. Different skills and equipment are needed, such as ice axes, crampons and specialist clothing. It is not within the scope of this guidebook to describe canyon descents at this time of year. Nevertheless, it is a sport gaining in popularity.

Spring is generally too wet for alpine canyoning. Long periods of rain can render all descents impossible, and the canyons draining the higher slopes become swollen with melt-water. Additionally, dangerous pockets of snow can persist in sun-deprived canyons until early summer.

Visiting in early summer is a possibility. June, for example, is often a pleasant time in the Alps. The heat isn’t as intense, the mountains are lush green and there are far fewer tourists around. Rainy days may be more frequent, but certain descents remain feasible or even preferable, depending on your level of expertise and thirst for challenge. Ticino in particular enjoys a slightly longer season than the rest on account of its many hydroelectric installations, which act to moderate the flow of water (see the Ticino chapter for details). Be warned, however – the more aquatic canyons will be very dangerous at this time of year.

Getting there

By air

The Val d’Ossola, Lake Como and Ticino areas are all within a 90-minute drive of Milan. The plethora of cheap flights to Milan’s airports makes it the first choice destination. These are, from west to east – Malpensa, Linate and Orio al Serio (in Bergamo). Malpensa airport is best for Val d’Ossola and Ticino, but there isn’t a great deal in it, and there are also trains from Geneva airport to Domodossola. For the Dolomites, flying to Venice Marco Polo or Treviso are generally better options, as Milan is a three- to four-hour drive away. For Carnia and the Julian Alps, which are further east still, Trieste and Klagenfurt serve as well as the Venice airports. Zurich airport is also convenient for the Ticino area, being about a two-hour drive or train journey away.

By train

All areas are well served by rail (see individual chapters for details). Useful websites are www.raileurope.co.uk and the national rail websites of Italy and Switzerland, respectively www.ferroviedellostato.it (or www.trenitalia.com) and www.sbb.ch.

By car

Anyone intending to drive from the UK or northern Europe should bear in mind that the journey time from Calais to Biasca, in the Ticino region, is about nine hours (if you’re lucky), and involves nearly 1000km of driving and multiple toll booths. Val d’Ossola, Lake Como and the southern Dolomites are about one, two and four hours further on respectively.

Getting around

For most areas, a car is essential given that most canyons are accessed by minor mountain roads not served by public transport. It is often better (and frequently necessary) to have two cars for shuttling people between start and finish, where a long walk would otherwise be necessary. Some canyoners opt for a car and bicycle. On busier roads hitch-hiking may be an alternative to two cars, and is generally quite easy in the Alps. The distance of any shuttle-run is given in the route description for each canyon to help you decide at a glance whether one or two cars are needed. Canyoning by public transport is only a possibility in Ticino, which has a frequent and reliable bus service and where canyons are close to main roads but the buses aren’t cheap.

Almost all the motorways, or autostrada, in Italy are toll roads, and toll booths are reasonably frequent. Cash and credit cards are accepted. There are no toll booths in Switzerland, but all cars driving on motorways (recommended to reduce driving times) are required to have an annual toll sticker, or vignette, displayed in the windscreen. These can be purchased at the border for a modest sum and are valid for 14 months, from 1 December to 31 January the following year. See the Swiss Federal Customs Administration website (www.ezv.admin.ch) for prices.

It is also worth noting that Italian sign-posting is frequently inadequate and inconsistent. Having a sat nav can significantly reduce the amount of time driving aimlessly back and forth!

The approximate driving times and distances between the four areas are given below.

Walk-in along Valle di Darengo (Route 44 at the north of Lake Como) (photo: Simon Flower)

Waymarking, access routes and maps

Approach walks vary from the very straightforward to the virtually invisible or physically brutal. Some approach walks make use of existing walkers’ paths (many of which are numbered in the Italian Alps); others have breathed new life into paths that would otherwise have crumbled away. Splashes of paint are frequently used to make route-finding easier, although the sight of paint should not necessarily reassure you that you’re on the right track. One marker that can be trusted though is the distinctive Associazione Italiana Canyoning (AIC) emblem – a blue spot on a white background (Italy only).

Owing to these route-finding difficulties, a necessarily detailed walk-in description is given in this guide for each canyon, along with a sketch map. Be warned that things change. Depending on a canyon’s popularity, a walk-in may become more or less obvious over time, or may change altogether if a preferred route is found. Access rights change over time too, so what may be freely accessible now may be out of bounds by the time you arrive. Seek local advice if uncertain.

Access to canyons can be complicated – if in doubt (in Italy) look out for the AIC marker (photo: Simon Flower)

Detailed topographic maps are usually unnecessary, but those wishing to buy them will find details in the ‘Practicalities’ section near the start of each regional chapter. They will certainly be needed if you wish to do any walking or via ferrata in the area. On the other hand, a good road map is very useful (1:200,000 or better). There are many such maps available, but perhaps the most convenient are the 1:200,000 Touring Club Italiano maps. These cover the whole area of this guidebook in just two sheets: ‘Lombardia’ (which covers Val d’Ossola, Ticino and Lake Como) and ‘Veneto-Friuli Venezia Giulia’ (which covers the Dolomites, and Carnia and the Julian Alps).

The risks of canyoning

Although most trips will pass trouble free, accidents do happen. Understanding the risks can help prevent accidents and prepare for their eventuality.

High water

Drowning remains the number one cause of death when canyoning. Sudden flooding is the main culprit (see ‘Sudden flooding’, below), and in addition many people underestimate water levels even before committing themselves to a descent. Prolonged periods of rain or a wet spring mean that the canyons will be wetter than normal in the summer, thus increasing their difficulty above the grade quoted in this guidebook. Get an idea of the water levels in the area before attempting more difficult canyons. Keep an eye on the weather a week or two before you arrive, and bear in mind that the flow rate in dam-regulated rivers may change over time (see Route 54 Grigno or Variola Inferiore, in Route 4, for a case in point). Comparing current flow rates in rivers with historical data is a useful trick, but such data is hard to find and will not be easy to access when abroad. For Ticino, hydrological data is available at www.bafu.admin.ch.

An unavoidable soaking in Clusa Inferiore (Route 59 in the Belluno Dolomites)

The main white-water hazards are turbulent plunge-pools. The high air content in white water renders it very difficult to remain afloat or swim in, while downward currents at the base of waterfalls and at the pools’ edges can actively drag a person underwater. Such hazards are better avoided than tackled head on. This can be achieved either by jumping clear of the danger (a solution with obvious risks) or by manipulating the abseil trajectory using deviations or guided abseils (see ‘Canyoning rope techniques’, below). Strong currents elsewhere may sweep people over waterfalls or dash them against rocks. If carried by the current, lying on your back, feet downstream, will reduce the chance of serious injury. Watch out for siphons, potentially lethal hazards that lurk hidden among submerged boulders. The gaps between the boulders create strong currents which can suck body parts in, trapping people underwater.

Sudden flooding

Flooding can be caused by heavy or prolonged rain, snow-melt, or the release of an upstream dam. It is important to assess the risk of each before setting out. If waters rise seek high ground (dry vegetation and trees are a good sign) and wait. Do not be tempted to push on downstream until water levels have returned to normal.

Rainfall

Significant rainfall is brought about by frontal systems and afternoon storms. Fronts may bring prolonged periods of rain to large areas of the Alps, whereas afternoon storms are short-lived and very localised, but frequently severe. The latter are brought about by cumulonimbus clouds, which develop from ordinary cumulus clouds as moist air rises throughout the day, a process accelerated by high temperatures and mountain relief. These storms are more common in northern Italy and Ticino than anywhere else in the Alps, owing to the moist, warm Mediterranean air travelling up from the south. Unlike fronts, which are easy to predict, forecasting afternoon storms is difficult. It is therefore vital to get frequent weather updates and to keep an eye out for cumulonimbus development. Weather reports are available in tourist information offices, campsites and local newspapers. Relevant websites are given in each chapter.

Floods can make a huge difference to the condition of a canyoning route (left: before flooding, right: after flooding)

Snow and glacial melt

Melting snow and ice can lead to dangerously high water levels as the day heats up. This is mainly a problem of canyoning early or late in the season. Few canyons in this guidebook have significant snow fields present in their catchment areas during the summer months.

Presence of upstream dams

Many canyons in the Alps have hydroelectric constructions somewhere along their length. Surprisingly, given the growing popularity of canyoning as a sport, it is difficult to find definitive information on their purge/opening patterns. Put simply, there are three basic types of construction

a grill in the stream bed which pipes away water to a nearby reservoir or power plant

a small dam that traps water first before piping it away

larger-scale dams, holding back millions of cubic metres of water, which is piped off to the power plant. Water may be piped into the reservoir from a number of sources.

When a single river intake closes (due to obstruction, malfunction or maintenance purposes), the water normally diverted away will return to the natural riverbed. Unless the river is large this is unlikely to cause problems for the canyoner. If the whole power plant needs to be shut down, or if rainfall is especially heavy, even the larger reservoirs fill and may be forced to open their overflow gates. A release of such vast amounts of water would be disastrous to unwary canyoners downstream. The smaller dams are also dangerous. They may be ‘purged’ after rainy periods to flush away sand and other debris that could otherwise harm the system. In short, the flow of a river below a hydroelectric installation may suddenly increase without warning, even in times of good weather.

In Switzerland it is usually possible to ring somebody to determine the risk of the dam opening (although the hydroelectric companies still decline all responsibility). In Italy this sort of service is by no means standard, and a certain degree of risk often has to be taken.

Jumps and toboggans

It would be fair to say that anyone who wasn’t prepared to jump or toboggan anything wouldn’t be getting the most out of this sport. As well as being great fun, these techniques speed progression and, in certain circumstances, may actually be safer than abseiling (for example, if an abseil deposits you in the worst of the current). That said, the Fédération Français de la Montagne et de l’Escalade (FFME) reports that half of all rescues arise due to misjudged jumps, with a smaller number attributed to toboggans. Injuries are more likely with jumps over 4m. Abseil to verify pool depth if there is any uncertainty. Note that canyons can change drastically over time – pools silt up or fill with detritus washed down by floods. To reduce the chance of injury, jump with legs together and slightly bent, flexing on entering the water. For toboggans, keep feet together and elbows away from the rock.

Jumping is a useful technique and great fun, but it carries obvious risks (Route 82 in the Carnic pre-Alps)

When toboggans go wrong! The 20m toboggan in Combra (Route 27 in the Ticino region)

Waterfalls and abseils

Use a hand-line to approach exposed pitch-heads, and clip into the anchor while rigging. Tie long hair back to reduce the risk of it being sucked into the descender. Although sharp edges can damage ropes, the majority of abseil problems arise due to high water (see ‘Canyoning rope techniques’ below).

Slippery rock

Falls resulting from slippery or loose rock account for about a third of all canyoning injuries. Some rock types provide good friction but become slippery when wet, particularly when covered in a layer of algae. Good shoes are essential (see ‘Equipment and clothing’, below). Be sure to test out their grip when first entering the canyon.

Rockfall

Rockfall is a greater risk in drier canyons, where loose rocks tend to loiter at pitch-heads. Rocks also get thrown in from above and blown in on windy days (when it is better to avoid tightly encased canyons).

Hypothermia and exhaustion

A warm, well-fitting wetsuit is essential (see ‘Equipment and clothing’, below). The chances of hypothermia are increased if exhausted, so physical fitness, food and fluids are important; it is easy to forget to drink when constantly immersed in water.

Absence or failure of in-situ equipment

The quality and positioning of in situ equipment varies greatly from canyon to canyon and from one pitch to the next. Even good quality rigging may be damaged by floods or rockfall. The quality, state and position of all equipment needs to be scrutinised before deciding whether or not you want to risk your life on it. Where possible avoid single-point anchors. Back up hand-lines with a belay or rig your own. In less frequented canyons, or those that are badly flood prone, be prepared to replace damaged anchors or slings.

Rope loss or damage

Losing a rope is a nightmare situation. At best it is an expensive mistake. At worst it prevents further descent and escape. A rope may get stuck when pulling through, or entangled in flood debris at the foot of a waterfall. Good rope management is key in preventing this (see ‘Canyoning rope techniques’, below). Ensure that all tackle-sacs have a flotation device (an empty bottle or waterproof drum) and take extra care in high water not to allow them to get swept downstream (do not throw them down pitches unattended!). Ropes also get damaged, for example when abseiling over sharp edges (a rope severs with surprising ease when under load). There are several methods to avoid this (also discussed below). Best practice is to carry a spare rope, so the canyon can be completed safely if a rope is lost.

Canyoning rope techniques

It is assumed that the reader is able to abseil proficiently and has a thorough practical knowledge of basic rope techniques. Therefore they are not described in detail here. Alpine canyons are not the places to learn these skills.

Below is a basic summary of the techniques appropriate to canyoning. Further information can be found in the resources listed in Appendix B.

Single-rope technique

When abseiling, climbers typically use the whole rope, doubled over and thrown down the pitch (the double-rope technique). This technique is both time-consuming (as all the rope has to be paid out, then packed away again) and potentially dangerous in wet canyons, where

turbulent plunge-pools will cause any excess rope to tangle, making the rope difficult to release from a descender

the excess rope may get trapped around submerged branches and boulders

the two strands of rope may twist around each other into a friction knot, making the rope difficult to pull down.

Using single-rope technique in Pontirone Inferiore (Route 29 in the Ticino region)

Using a guide-line to steer clear of the current during a ‘wet run’ in Cormor (Route 49 in the Lake Como region)

Although double-rope technique has its place, single-rope technique is infinitely more suited to canyoning. The main advantage is that the rope length can be ‘set’ to the length of the pitch. Where pitch length is uncertain, the first person can be put on belay using one of the releasable rigs described below. They can then be lowered if the rope turns out to be too short (communicating this need may have to be through pre-agreed shouts, whistle blasts or hand gestures). The remainder of the rope, still in the bag, can either be brought down by the next person, zip-lined down the abseil rope or (if sensible to do so) thrown down to waiting team mates. The two ends of the rope can now be kept well clear of each other, ensuring a trouble-free pull-through.

Another advantage of single-rope technique is that it is easier to steer the course of an otherwise aquatic abseil by means of deviations (where the abseil rope is clipped into intermediate anchors) and guided abseils (a taut line secured between the top and base of a pitch, into which abseiling canyoners can clip their cow’s tails).

The main disadvantage of single-rope technique is the risk of rope damage. Single ropes stretch and bounce more than double ropes, increasing the sawing action over sharp edges. If sharp edges are anticipated, the options are to:

run the rope over a tackle-sac secured to the rigging above (a method which is effective only if the rub-point is near the pitch-head)

pay out/take in rope between abseils to vary the position of the rub-point

use double-rope technique.

Releasable rigs

Although they are more time-consuming to rig, releasable systems should be used when possible in technical canyons. If a team mate gets strung up mid-rope (for example if hair, a glove or wetsuit gets caught in the descender), they can be quickly lowered out of danger.

Methods include

an indirect belay (very quick and simple)

a direct belay (an Italian hitch is often used)

the figure-of-8 block.

The figure-of-8 block works well (see photos 1 to 6 for how to tie one) and is the technique most commonly used on the continent. With the other two methods, the last person down needs to convert the belay to a non-releasable system.

The figure-of-8 block

1 Thread the figure-of-8.

2 Cross the rope (important: not doing so may result in the device being difficult to undo when loaded).

3 Pass a bight of rope up through the large ring

4 Pull the loop down and 5 pass it over the small ring.

6 Pull everything tight. To prevent people abseiling on the wrong end, a quick-draw could be clipped between the small ring of the figure-of-8 and the anchor (do not use an ordinary karabiner for this purpose – it will be difficult to undo under load).

A clove hitch and locking karabiner (top) and a stopper-knot crabbed to the live rope (bottom)

Non-releasable rigs

a clove hitch and locking karabiner (see photo) (important: ensure that the knot lies away from the gate and that the gate is locked – a twist-lock karabiner is recommended here), and

a stopper-knot crabbed to the live rope (see photo). This may be safer in the absence of a twist-lock karabiner, but the knot can be difficult to undo. Also, the rope can be more difficult to pull through from an oblique angle.

All these systems are fairly bulky and have the potential to jam when pulling through. If this is anticipated the last person down can remove the knot or figure-of-8 device, then either use double-rope technique or have the live rope counterweighted by team mates waiting below (the ‘fireman’s belay’).

Whichever method is used, the last person to descend should be confident that the rope will pull-through.

A FEW TIPS FOR ROPE MANAGEMENT

Pack the rope so that you can get easily at both ends in the tackle-sac. This will be useful when tying two ropes together or rigging traverses.

Flake the rope into the tackle-sac rather than coiling it. A three-person approach will speed things up – one to pull down, one to hold the bag open, one to pack.

While a number of knots are suitable for joining ropes together, a double overhand knot (see photo) is quick, simple, safe and easy to undo after loading. It is also asymmetrical, reducing the chances of it jamming. Tie two neatly laid overhand knots very close to each other, with a 30cm tail. Warning Do not use a figure-of-8 knot in this situation. It rolls back on itself, and those with short tails can completely undo at loads as low as 50kg.

At intermediate ledges on multi-pitch abseils, thread the pull-down rope through the next anchor before pulling-through. This limits the chances of the rope getting dropped down the pitch.

A double overhand knot – a quick and effective method of attaching two ropes together (photo: Simon Flower)

ABSEILING INTO TURBULENT PLUNGE POOLS

If abseiling into turbulent plunge-pools, take the following steps to reduce the risks of entanglement and other problems.

Do not tie stopper-knots in the end of the rope.

Do not use prusik loops or shunts to control the rate of descent.

Consider zip-lining tackle-sacs down the abseil rope, rather than abseiling with them.

Try to release the rope from your abseil device before entering the water or, if this is not possible, swim away into calmer water first.

If you anticipate submersion, taking three or four deep breaths beforehand will increase the time you can hold your breath.

Those standing by at the bottom should have a throw-rope ready to pull people out of danger.

Equipment and clothing

Although canyoning requires relatively little equipment, dedicated canyoning equipment is quite difficult to obtain outside the canyoning regions of mainland Europe. In the UK, although climbing shops suffice for many things, caving shops may be a better source for more canyon-specific items such as semi-static ropes, robust wetsuits and tackle-sacs. A list of UK caving shops that may be useful is included in Appendix B. They may also be able to order things if they don’t have them in store.

There is a greater selection of canyoning equipment available on the continent. A good place to start is www.expe.fr or www.resurgence.fr, both online shops in France. Canyoning equipment is also available from smaller shops locally. Details of known suppliers are given in each chapter.

Personal kit

Clothing

For the canyon Rivers in the Alps are cold. Some are glacial melt-water. A full wetsuit is therefore required, as close fitting as possible without being too restrictive of movement. Thickness is important, but a snug 3mm wetsuit with no air pockets is infinitely better than a baggy 5mm one. Surfing wetsuits are fine and readily available, but vulnerable to wear and tear. A tough pair of shorts (or a specialised harness – see below) will prolong the life of the seat, while neoprene pads (available from caving or skateboarding shops) are useful for knees and elbows. Caving oversuits can give excellent protection (and additional warmth), but at the expense of freedom of movement.

Specialist wetsuits are available that have zip-up fronts, fitted hoods and reinforced areas, but these are hard to find in the UK (although you may find something similar in caving shops). Neoprene socks are advised – and the thicker the better. Gloves and neoprene hoods are by no means vital, and the decision to use them will depend on personal preference. Hoods dramatically reduce hearing.

For the approach walk In general, the less worn the better; you will only end up having to carry it down the canyon. Shorts worn for the walk-in can be used to protect the seat of the wetsuit in the canyon.

Footwear

Footwear needs to be light, well made and well draining. Trainers are fine but offer little ankle support, while heavy walking boots provide little grip on account of their inflexibility. Rubber wellingtons are tough, cheap and provide fantastic grip, but don’t drain at all and impede swimming. Specialist canyoning shoes (such as those by Five-Ten, Adidas& & & or Etche) are available in the UK, but most shops normally need to order them in specially.

Harness

Any caving or climbing harness is suitable. Caving harnesses are more efficient if you need to prusik and are more durable. A few specialised canyoning harnesses are available in the UK, but again may need to be ordered in. These have a built-in seat protector to help prolong the life of the seat of the wetsuit. Seat protectors compatible with caving harnesses may also be available to buy separately. Check harnesses routinely for signs of wear and tear.

Descender

A number of types are available, but none is perfect (see ‘Choosing your descender’, below). Whichever device you choose, know how to lock it off and add friction mid-descent.

Helmet

Head injuries may result from slipping on wet rock, rockfall and from being tossed about by the river’s current. Always wear a helmet in alpine canyons.

Flotation device

A flotation device, such as those used for white-water kayaking, can provide peace of mind in very wet canyons, although they impede swimming performance.

Self-rescue and rigging equipment

How much of this is carried as personal kit and how much is shared between the group as a whole depends on personal preference. Everybody should have some means of ascending the rope, whether prusik loops, lightweight jumaring devices, or full-size jumars used by cavers. A figure-of-8 can be useful for rigging releasable belays (see ‘Canyoning rope techniques’, above) and will double as a spare descender in case one is lost.

Knife

Use this for cutting rope or freeing companions should they get trapped under the flow of water. Folding knives are available that clip safely to a karabiner, such as that made by Petzl.

Cow’s tails (or lanyards)

These are useful for clipping into the anchors at the top of pitches or traverse lines. A 3m length of 9 or 10mm dynamic rope is sufficient to tie two long cow’s tails. A short cow’s tail is also useful – a quick-draw or similar is recommended.

Descending into Giumaglio’s more vertical second half (Route 19 in the Ticino region)

Whistle

A loud whistle may be useful for communicating over the din of a large waterfall, but it is very annoying for everybody else in the canyon. Use sparingly!

Group kit

Rope

The choice of rope for canyoning is a tricky one. All caving and climbing ropes are safe, but certain types are better suited to canyoning. There are numerous points to consider (see ‘Choosing ropes’, below).

Security rope

This is an optional throw-rope, useful in high water conditions for assisting team mates out of white-water hazards. Have it ready to hand rather than stuffed at the bottom of a tackle-sac.

Tackle-sac with flotation

A sturdy PVC tackle-sac with many drainage holes (or mesh sides) is essential. In general, standard caving tackle-sacs are not suitable. Without drainage holes bags will be excessively heavy and straps will break under the strain. Tackle-sacs should be big enough to accommodate rope and a flotation device, such as an empty bottle or waterproof drum, which should be secured to the bag by some means.

Waterproof drums and dry bags

These are needed to provide flotation to the tackle-sac and to store food, first aid kit (see below), dry clothes, headlamp and so forth. A separate key carrier (for car keys, mobile phone, money, etc) is useful just in case the drum leaks. Dry bags should not be relied upon for flotation – they usually deflate.

Emergency rigging equipment

Carry a length of cord for making anchors. A ‘lightweight’ bolting kit, such as those used for expedition caving, is useful for less popular or flood-prone canyons (most alpine canyons!).

Diving mask or goggles

These can be useful for assessing pool depth and searching for sunken equipment.

Camera

A waterproof digital camera is useful for recording guidebook information, so that the book need not be damaged by taking it canyoning. However, they don’t always take the best photos (see ‘Cameras and photography’, below).

First-aid kit (and mobile phone)

A first-aid kit should include pain-relief medication, gaffer tape and a survival bag as a minimum. A small splint such as a SAM splint is highly recommended. If going to north-east Italy, take fine-tipped tweezers or a specialist tick-removing tool (see the introduction to ‘The Belluno and Friuli Dolomites’ for details). Mobile phones may work in some canyons.

Choosing ropes

There are a number of points to consider.

Number and length

The route summary table (Appendix A) will help in choosing the length of rope needed.

Note that with repeated wet–dry cycles a rope can shrink by ten per cent of its original length, sometimes more. It is advisable to soak and dry the rope a few times, then measure it again before using it. Bear in mind that pitch lengths quoted in this guide assume a pre-shrunk rope. Best practice is to carry a spare rope, so that the canyon can be completed safely if a rope is lost.

Dynamic versus static/semi-static

Semi-static ropes are most suited to canyoning, offering far greater control when abseiling and prusiking. They are dangerous for lead-climbing, but if this need arises (for example, if a rope gets stuck) tying three or more knots next to the harness will increase the dynamic nature of the rope a little.

Colour

Ropes of differing colours would be an advantage to aid with untwisting them before pulling through.

The final encased section in Fogarè Inferiore (Route 62 in the Belluno Dolomites)

Diameter

The diameter affects the weight and durability of the rope. Thick ropes (>10mm) have a longer life span, but are heavy when wet and take up more space in bags. On the other hand, the bounce on thin ropes is greater, thus increasing the sawing action over sharp edges – beware!

Flotability

A few manufacturers produce special canyoning ropes that float, with obvious advantages. However, they are made of polypropylene rather than polyamide, which takes less punishment before breaking. Polypropylene melts at about 160°C and must therefore be used wet.

Choosing your descender

For the lack of a perfect device, the figure-of-8 is most often used by our European neighbours. It is cheap, lightweight, provides a smooth abseil and can be used with single or double ropes. For canyoning a figure-of-8 is better threaded differently to the usual method (see photo). This alternative method enables the device to be kept on the karabiner at all times and therefore reduces the very real risk of it being dropped while loading or unloading ropes.

The figure-of-8: canyoning set-up

The figure-of-8: extra braking

The Petzl Pirana (see photo), designed especially for canyoning, eliminates this risk altogether. It also prevents cross-loading an open screw-gate, a potentially fatal side effect of normal figure-of-8 usage. The rope runs quicker in the canyoning set-up, although there are several methods for increasing friction, such as putting in an extra twist or running a loop back through a karabiner clipped to the harness.

The most significant drawback of figure-of-8 use is that it twists the rope. At the least this can cause problems with rope retrieval, particularly if double-rope technique is used. On longer abseils it can cause a great nest of rope to bunch up beneath the device, making further descent impossible if not noticed in time.

Common alternatives to a figure-of-8 are a rack, a bobbin device and a standard belay device. None of these cause rope twisting, but all have their own drawbacks.

Racks

A rack is heavy and pendulous, time-consuming to rig and very difficult to release in turbulent water. Double ropes can be used, but may jam if previously twisted by figure-of-8 use. Racks are not recommended for aquatic canyons.

Bobbin devices

Bobbin devices give a horrible jerky descent in inexperienced hands (bounce = sawing action) and can’t be used with double ropes. Bobbin devices with an automatic brake (such as the Petzl Stop) provide the most control over any device, but require two hands to operate – not always easy in high water.

Belay devices

Standard belay devices are cheap, lightweight and can be used with double ropes, but controlling speed is difficult and they are easily lost when unloading them in turbulent pools. Belay devices are not recommended for canyoning at all.

In addition to these is the Kong Hydrobot, another specialist canyoning descender, currently unavailable in UK high streets. It is essentially a single-barred rack – much less cumbersome than a standard rack and certainly much easier to rig and release. A central bar keeps double ropes separate, reducing the chances of jamming if twisted. However, it is dangerously slick when used with new or small-diameter single ropes, and applying extra friction or stopping mid-descent is not at all easy or reliable. Use the Hydrobot with caution.

The Petzl Stop, Kong Hydrobot and Petzl Pirana (photo: Simon Flower)

Canyon safety – precautions and pre-trip preparations

To help prevent accidents, and prepare for their eventuality, consider the following points.

Before leaving home

Take out rescue insurance and know how to summon a rescue if needed.

Learn some first aid, ideally with a wilderness slant – rescue can be a long way off.

Get a European Health Insurance Card.

Soak, dry, then remeasure your rope – it could shrink by 10 per cent of its original length.

Familiarise yourself with canyoning risks and techniques, and have the correct equipment.

Keep an eye on the weather a couple of weeks prior to your trip.

Before going canyoning

Familiarise yourself with the route, making a note of specific hazards and escape points. Take a photo of the route in the guidebook, if taking a digital camera into the canyon.

Know where the nearest hospital is.

Leave a call-out, and make sure the person with your call-out knows what to do if you are overdue.

Know your team well and limit party size on long or technical trips. Consider hiring a guide if uncertain.

Assess water levels in the canyon.

Determine flood risk (check the weather forecast, assess for snow-melt and, if possible, phone any upstream dams).

Check equipment for signs of wear and tear, especially harnesses and ropes.

A phone call can save lives (photo: Simon Flower)

Capturing moving targets in poor light is one of the major challenges of canyon photography (Route 33, Ticino)

Cameras and photography

Canyoning presents unique challenges for the photographer, and no camera is ideally suited to the task. While waterproof compact cameras are perfectly adequate for sunny scenes (and are great for getting close to the action), they fall short in low light conditions. Digital SLRs (DSLRs) are capable of far superior photos and perform much better in low light, but are expensive and bulky (especially with the sturdy waterproof box required). The newer mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras are lighter than DSLRs, but lack some of their functionality. (The photographs in this book by Andrew Atkinson were taken with a Pentax K100D digital SLR with an SMC Pentax-DA 14mm f2.8 lens.)

The problem with low light

In low light, a camera set to auto may do one or more of the following.

Increase the aperture This reduces the depth of field, which could result in unwanted blur or ‘bokeh’ (more likely with telephoto lenses).

Decrease the shutter speed This could result in blurred subjects or scenes.

Increase the ISO This makes the sensor more sensitive to light, but images tend to be grainier and less detailed. The large sensors in DSLRs cope far better with high ISOs than the tiny sensors of compact cameras. At ISO 800 (frequently required when canyoning), shots taken with a compact camera often look terrible.

Fire the flash. In-built flashes are not usually powerful enough and often create a snowstorm scene as their light reflects off airborne water droplets. Better to turn the flash off.

Tips to improve photos in low light

Take control over aperture, ISO or shutter speed. This is usually easy with DSLRs, impossible with compacts and long-winded (via fiddly on-screen menus) with mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras.

Buy a camera with good low-light/high-ISO performance, a good image stabiliser and a ‘fast’ lens (ie one with a low f number). Telephoto lenses are best for close-up action, but wide-angle lenses (ideally 28mm equivalent or less) are far more versatile, generally ‘faster’, and retain a good depth of field at wider apertures.

Shoot in RAW (rarely possible with compact cameras). Difficult lighting means photos are rarely perfect straight out of the camera. RAW files can be adjusted later. If your camera lacks RAW, avoid combining a dark canyon interior and bright skies in the same shot.

Deliberately underexposing by 0.5–1.5 stops helps to keep ISOs down and shutter speeds up. Bright areas are less likely to be blown out, while darker areas can usually be recovered later (if shot in RAW).

Some welcome sunshine towards the end of Osogna Intermedio (Route 35, Ticino) (photo: Simon Flower)

Carrying and protecting the camera

Waterproof cameras can be attached (via the wrist-strap) to the chin-strap of a helmet, then tucked down the front of a wetsuit. As well as being secure and quick to hand, the neoprene will protect the seals from excessive water pressure (waterfalls and jumps can cause unprotected cameras to leak).

DSLRs obviously need more sturdy protection. The most convenient is a Peli Case or similar. Plastic sandwich bags are a cheap and effective way of keeping the spray off the camera while in use, and travel towels are a good way to dry hands and lenses. Always use a clear filter to protect the lens (look out for ones with a waterproof coating – others deteriorate quickly).

Mountain rescue, local healthcare and insurance

All the countries in this guide provide an excellent mountain rescue service, but in most of continental Europe mountain rescue is not free. If a rescue is called, you will be charged, usually a considerable sum. Therefore, it is important to be adequately insured. Suitable insurance can be obtained through (for example) the British Mountaineering Council or the UK branch of the Austrian Alpine Club. Other insurers may also cover canyoning, but it would be well worth a detailed check of the terms and conditions as the sport is not well known in the UK.

Canyoning injuries are reasonably commonplace, and (with a lack of mobile phone reception in canyons) rescue is often a long way off. First-aid knowledge (and a first-aid kit) is therefore invaluable. There are many excellent courses available that have a specific slant on wilderness medicine. It is important for teams to be adequately equipped and resourceful, and to have sufficient skills to deal with lesser emergencies themselves. Mountain rescue should be considered only as a last resort for major emergencies.

Emergencies

If in doubt dial the International Rescue Number: 112

Switzerland

Police……………….117

Fire…………………118

Ambulance…………….144

Air Rescue…….1414 (Swiss SIM cards)

…….+41 333 333 333 (other SIM cards)

Italy

Carabinieri…………112

(calls to this number can be directed to other emergency services, in line with other European countries)

State police………….113

Fire…………………115

Ambulance and mountain rescue…………………118

Austria

Police……………….133

Fire…………………122

Ambulance…………….144

Mountain rescue……….140

Slovenia

Police……………….113

All other emergencies, including mountain rescue…………….112

All areas described in this guide are well served by hospitals with emergency departments (detailed in their respective chapters). Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Slovenia offer excellent standards of healthcare.

UK residents should apply for a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which gives the holder a reciprocal right to healthcare when visiting countries of the European Economic Area and Switzerland. However, this does not mean that health care abroad is free. The expected fees are detailed in the table below (travel insurance can help offset some of these costs). This information is subject to change, and updates can be found at www.travelinsuranceguide.org.uk.

HELICOPTER RESCUE

Before phoning, think whether helicopter rescue is feasible.

Is it possible to land or will a winch be needed?

Are there obstacles near the accident site (such as cables)?

When a helicopter approaches:

signal whether rescue is required, and

do not approach the helicopter until the rotor has come to a standstill.

EXPECTED COSTS WITH A EUROPEAN HEALTH INSURANCE CARD

| Italy | Prescriptions – free or non-refundable fixed charge (depending on drug)Doctors – no chargeHospital – treatment free. Possible drug and ambulance fees (depending on area), which may or may not be refundable. |

| Switzerland | Prescriptions and doctors – fee charged but can be reclaimedHospital – refundable fees plus non-refundable fixed charge (the ‘excess’) and a non-refundable daily contribution towards bed and board. Also a charge for 50 per cent of the cost of ambulance transport, including air ambulance. |

| Austria | Prescriptions – non-refundable fixed feeDoctors – fee charged (may be entitled to a partial refund)Hospital – non-refundable fee for first 28 days. Refund may be possible in private hospitals. |

| Slovenia | Prescriptions – non-refundable fees. Charge depends on drug.Doctors – non-refundable feeHospital – free apart from a non-refundable fixed daily fee |

Canyon etiquette

Some of the most highly prized canyons in Europe are out of bounds to canyoners. Many more are at risk of going the same way. Canyons in national parks or other protected areas are particularly susceptible to legislation, but so too are those whose course or access routes pass through private property. The canyoning community lacks the political swing of its mountaineering or speleological counterparts, so once a canyon has been prohibited from use it generally remains so. It is important, therefore, to be responsible and avoid treading on any toes.

Do not park on private land.

Choose your changing areas well. Nobody wants a group of rowdy foreigners parading naked around their village.

Be courteous to locals and other canyon users alike (see ‘A note on guided groups’, below).

Restrict party size. While large groups are safer in the event of an accident, they are slower (risking hypothermia or benightment) and antisocial for others groups present in the canyon.

Pay heed to local bye-laws and do not trespass. Information presented in this guide may change; seek local advice if there is any doubt.

Respect the environment. With a climate that differs markedly from the world above, canyons are unique ecosystems, populated by plants and animals seldom found elsewhere. Follow the old adage ‘Leave nothing but footprints’, and go quietly so as not to disturb the wildlife. Birds, for instance, are easily disturbed by groups of canyoners whooping and hollering their way down waterfalls.

Take care not to disturb the wildlife

A note on guided groups

Canyoning in the more popular areas of southern Europe generally entails meeting long lines of identically clad adventure tourists, usually waiting around at pitch-heads as others in the group get ceremoniously lowered over on a rope. Thankfully, owing to the length and more technical nature of the canyoning in the Alps, this situation seldom arises here. Guided groups do exist, but are fewer in number and generally smaller in size. Outside the peak holiday season in August you may well meet none at all.

If you do happen across a group, be courteous. Remember that the guides with them may have installed the nice shiny anchors that you’re using, and most will let you pass as soon as is safe. It is bad form to loiter behind in order to find out where all the good jumps and toboggans are!

Finally, if a canyon seems too daunting consider hiring a guide. Local tourist information offices (see Appendix D) usually have details.

Using this guide

Canyon nomenclature

The naming of canyons is by no means consistent. One canyon may have several aliases, even within the canyoning community. Canyons may be named after the river itself or the valley the river runs in, which are not always the same. They may take the name of a nearby village or a nickname given by locals or canyoners. In this guidebook, the name given is that most commonly used by canyoners, but alternatives are supplied where necessary.

Many canyons are divisible into two or three separate parts. Where each part is a distinct trip in its own right, with a well-defined access route of its own, it is named according to local convention, for example Superiore, Intermedio and Inferiore (upper, middle and lower) or 1, 2, 3.

Divided up in this way, there are 101 canyoning trips described in this guidebook. Ninety of these are worthy of specific mention and are numbered 1 to 90 accordingly. Eleven of these routes have an additional canyon nearby described – one not worth visiting on its own, but worth doing if you’re in the area. These additional canyons have ‘a’ in the route number.

Quality rating

This book contains a select group of canyons, chosen from a multitude of others available in the area. While all are celebrated in one way or another, some are more memorable than others. The five-star quality-rating system used in the guide (shown in the box at the start of each route) takes account of both beauty of the canyon and level of sport it offers.

Although the ratings reflect the opinions of many, they are still only a guide. They are subject to personal taste and depend to a great extent on water levels in the canyon at the time of descent. In general though, five-star canyons are unforgettable experiences, providing continual entertainment (particularly jumps, toboggans and atmospheric abseils) in a setting of immense geological grandeur and scenic beauty. They should not be missed. Those with fewer stars have similar appeal but may lack the edge of five-star canyons; the canyon may be less continuous, less aquatic, less scenic or have fewer pools for jumping.

Difficulty and grading of canyons

The canyons in this guide are graded by difficulty using the system employed by the Fédération Français de la Montagne et de l’Escalade (FFME), the Fédération Francais de Spéléologie (FFS) and the Associazione Italiana Canyoning (AIC), which has been adopted by guides and guidebook authors throughout Europe. See below for a full breakdown of the grading system.

Although this grading system is useful in describing the most technically challenging aspect of the canyon, it does not give an idea of how physically demanding the route is or how sustained the difficulties are. The canyons in this guide are therefore also given a basic overall grade (shown in the box at the start of each route), based on the colours used to grade ski-runs. From easiest to hardest, these are green, blue, red and black.

Grading of canyons is not an exact science and the difficulty of any canyon will change depending on the levels of water. Water levels can vary somewhat from year to year, and an ‘easy’ canyon may well become incredibly dangerous after a storm or prolonged rain. However, the grading gives an idea of what to expect in average conditions.

The Route Planner at the back of the book shows the star rating and difficulty rating for each route to help you plan your trip.

Canyon grading system

The grading is calibrated for a party of five people who have no knowledge of the canyon but who have a level of experience and fitness appropriate for it. It is comprised of three parts – vertical character (v), aquatic character (a), and the level of engagement, indicated by a Roman numeral. The letters v and a are followed by a numerical value from 1 (easiest) to 7 (hardest), although the grading is open-ended. Both components may change over time as the quality of rigging (which safeguards climbs as well as aquatic abseils) improves or deteriorates. Engagement is rated from I (frequent escapes) to VI and beyond (few, if any, escapes). The result is a grade in the form v4.a3.IV, meaning the canyon has a vertical rating of 4, an aquatic rating of 3 and an engagement level of IV.

Rope length

With repeated wet–dry cycles a rope can shrink by as much as 10 per cent of its original length, which means that a factory-stamped 50m rope may well turn out to be a few metres short on a 50m pitch. All pitch lengths and rope lengths quoted assume the use of a pre-shrunk rope. It is therefore essential to soak and dry the rope a few times, then remeasure it, before canyoning with it for the first time. The topo should not be relied upon too heavily for individual pitch lengths, given the difficulty of measuring pitches accurately while canyoning.

Descent times

Descent times are only a guide. They are based on a party of four canyoners with a level of experience appropriate for the descent, and assume normal summer conditions.

AIC rigging

The Associazione Italiano Canyoning (AIC) has equipped a number of canyons across Italy. The rigging is generally of a very high standard on double P-hangars and chains in well thought-out positions. The list of canyons equipped is growing – check the ‘Progetto pro canyon’ link on the AIC website.

Low water levels makes Chiadola (Route 69 in the Friuli Dolomites) great for beginners

Tick rating

Tick bites are a particular risk in Carnia and the Julian Alps and in the Dolomites. In these chapters the canyons are given a tick rating, dependent on the chance of encountering ticks during approach walks. Walks are graded 1 = small risk to legs only, 2 = bites to legs guaranteed without protection, or 3 = bites everywhere a possibility (ie a proper thrash in the undergrowth!). Risk is greatly reduced by taking simple precautions (see the introduction to ‘The Belluno and Friuli Dolomites’ for details).

Left or right?

In describing directions on the approach walk or in the canyon, the ‘true’ (or ‘orographic’) direction is given if there could otherwise be confusion. For example the ‘true’ right of a river is the right side of the river when facing in the direction of flow.

TIP

If you are taking a digital camera along, take a photo of the canyon description, topo and access details to refer to if needed, rather than taking this book down the canyon.

KEY FACTS

Time zone GMT +1

Language Italy and Ticino – Italian; Austria and Swiss Valais – German; Slovenia – Slovenian

Currency Euro (€) in Italy, Austria and Slovenia; Swiss Franc (CHF) in Switzerland

Visas Not required for citizens of the EU, US, Canada, Australia or New Zealand if staying less than three months. South Africans require a ‘Shengen’ Visa, allowing travel across the borderless states of mainland Europe.

International dialling code Italy +39 (for landlines, the zero of the area code must be included in the number dialled; for mobile phones it must be excluded); Switzerland +41; Austria +43; Slovenia +386

Electricity Switzerland has a three-pin plug system, while Italy has two-pin plugs with two different diameters. Take a universal plug to be certain.

The spectacular pitch-head at the end of the second encased section of Lodrino Inferiore (Route 33, Ticino)