Читать книгу The Guardsmen: Harold Macmillan, Three Friends and the World they Made - Simon Ball - Страница 7

1 Sons

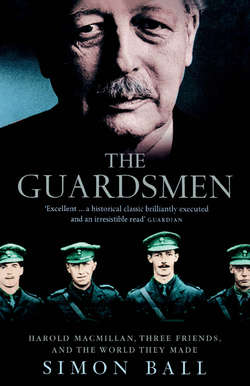

ОглавлениеHarold Macmillan, Bobbety Cranborne, Oliver Lyttelton and Harry Crookshank were members of a remarkable group. The four were born within a year of one another, Bobbety Cranborne, Oliver Lyttelton and Harry Crookshank in 1893, Harold Macmillan, the youngest of the quartet, in February 1894. As Lyttelton himself wrote, ‘Harold Macmillan went to Eton as a Scholar at the beginning of the school year of 1906. Strangely amongst his exact contemporaries at Eton were three boys, Cranborne, Crookshank and Lyttelton, all – like he – destined to be officers in the Grenadier Guards, all destined to survive…and all to be members of Mr Churchill’s governments in war and peace.’1

In the carefully cadenced world of Edwardian society, the four had started out not as a quartet but as two distinct pairs. Cranborne and Lyttelton were patricians, Macmillan and Crookshank ‘new men’. Eton was the clasp, a link sought quite consciously by the Macmillan and Crookshank families, that bound patrician and plebeian together. In the event this link was annealed by the Grenadier Guards.

The Lytteltons and the Cecils were aristocratic families who enjoyed a warm friendship. Not only was Oliver Lyttelton’s father, Alfred, close to Bobbety’s father, Jim Salisbury, but Oliver’s mother, Didi Lyttelton, and Bobbety’s mother, Alice Salisbury, were firm friends.2 In 1875 Jim Salisbury’s cousin, the future prime minister Arthur Balfour, fancied himself in love with Alfred’s sister, May. AJB was disconsolate at her early death from diphtheria, placing an emerald ring in her coffin. Naturally his friends rallied round. They rallied round once more in 1886 to console Alfred in his grief after the death of his wife, Laura, in childbirth just eleven months after their marriage. Alfred Lyttelton subsequently found solace in the love of a young beauty they had adopted into their circle, Didi Balfour. Her physical similarity to Laura was, some of his friends and relations thought, unnerving. Alfred and Didi married in 1892: Oliver was born within eleven months.

Oliver ‘had a hero worship of my father but stood in some awe of him’. It was hardly surprising. Alfred Lyttelton was the beau ideal of the muscular Christian. He was strikingly handsome, clever and well-liked. Beyond that, he was a true sporting celebrity, a natural at any game to which he turned his hand. These included both ‘aristocratic’ and ‘popular’ pursuits. He was a dominant figure at Eton fives, racquets and real tennis. He played football for England. He was best known as a ‘gentleman’ cricketer, second only to W. G. Grace in the England team, in which he played as a hard-charging batsman and as wicket-keeper. In middle age he took up golf with a passion that dominated Oliver’s childhood landscape. In 1899 he bought land near Muirfield and called in Edwin Lutyens to build him a splendid golfing lodge, High Walls at Gullane.3 It was a burden Oliver had to carry as he grew into manhood that, although he was big and tall, he could never approach his father in sporting prowess.

Oliver was, however, doted on by his beautiful but highly strung mother. She was much given to ‘premonitions’. She later became, somewhat to his embarrassment, one of the leading figures in the British spiritualist movement. She forced Alfred to give up High Walls because she could not bear the separations his golfing forays involved. Instead she found a new country home at Wittersham near Rye, where Alfred and Oliver could golf under her watchful eye. At an early age Mrs Lyttelton’s worries affected Oliver’s schooling. He was not sent to prep school as a boarder but instead attended Mr Bull’s in Baker Street with his cousin Gil Talbot, later a close Oxford friend of Harold Macmillan who was killed fighting on the Western Front in 1915.4 At one stage Alfred Lyttelton even wavered in his intention to send Oliver to Eton, where his family had been outstanding figures for generations, considering instead the merits of Westminster, where he would be a day-boy within easy walking distance of home.5

Alfred Lyttelton entered politics in his late thirties soon after his second marriage and the birth of his son. Like his Cecil friends Arthur Balfour and Jim Salisbury, he was a staunch Tory. After a relatively brief apprenticeship he was catapulted straight into the Cabinet by Balfour, who had himself succeeded his uncle, Lord Salisbury, as prime minister the previous year. Although many would feel jealous about such rapid advancement on the ‘Bob’s your uncle’ principle, Alfred in fact entered high office at a difficult moment. The Conservative government was on the ebb tide that would lead to its crushing defeat in the 1906 election. Lyttelton himself, as colonial secretary, was soon embroiled in the unedifying aftermath of the Boer War and in particular the issue of ‘Chinese Slavery’ in South Africa. Lyttelton was excoriated by sections of the press on the issue. He was used to adulation rather than criticism and reacted badly. After hearing him speak in the Commons, Lord Balcarres, a Conservative whip, observed that his speech was ‘able in its way but marred by a certain asperity of voice which is not borne out by his smiling countenance. The result is that the newspaper men think his remarks virulent and acrimonious, whereas members in the House itself (to whom he addresses himself exclusively), see by his face that he does not mean to be disagreeable. Hence the divergence of criticism between MPs and journalists.’6

Neither did Alfred Lyttelton have much taste for opposition. Party managers found the tendency of ex-ministers, of whom Lyttelton was one, to follow the example of Balfour, who lost Manchester and was returned for City of London, to gravitate towards town in search of safe seats comfortably near their homes ‘indefensible’.7 Lyttelton had bought 16 Great College Street, Westminster, in 1895 when he had become an MP; now he bought No. 18 next door and had Lutyens create a substantial house. Defeated at Warwick and Leamington, he was found the excellent seat of St George’s, Hanover Square. This ‘selfishness’ as far as the party in the country was concerned was compounded by ‘indolence’ in the House itself. He was accounted ‘tame and ineffectual’ in the Commons.8

British politics were moving into an exceptionally bitter phase as the Liberals, or ‘Radicals’ as the Conservatives preferred to call them, attempted to push through their ambitious social, financial and constitutional programme. It seemed to some Conservatives that they were engaged in a class war with enemies such as the Welsh Liberal politician Lloyd George and the socialists of the Independent Labour Party. Yet in the Lyttelton household the political creed of the latter was a suitable subject for humour: ‘I went to the Mission [in the East End of London],’ Oliver told his mother in 1908, ‘but I am still not yet a socialist. The “staff” are particularly nice as is only natural considering they are Old Etonians.’9 Alfred seemed ‘opposed to any actions except quiescence’ and was not in favour of the House of Lords wrecking Liberal legislation. He and his friends, ‘comfortable in rich metropolitan seats’, did not seem to register the depth of the crisis: if the Tories did not resist with all their might and main ‘we should look upon ourselves as a dejected indeed a defeated party’.10

The unpleasantness of politics communicated itself to Oliver: ‘I hope,’ he wrote to his mother from Eton in 1909, the year of Lloyd George’s ‘People’s Budget’, ‘we are very full for Christmas, I don’t mind sleeping on the floor, even if everybody is over thirty. I do hope there won’t be any ghastly election or any other political absurdity this time.’11; Unfortunately the political absurdity was unstoppable. In November Lloyd George described the peers as a useless group randomly chosen from among the unemployed and the House of Lords threw out his budget. That Christmas was ruined by an election in January 1910. The next Christmas was ruined by an election in December 1910. The elections solved nothing. The Liberals were weakened, indeed reliant on Irish nationalists for their parliamentary majority, but still in power. In front stretched the crisis of the 1911 Parliament Act, which was designed to cripple the power of the peers. Electoral failure in 1910 also brought about the fall of Balfour and the advent of the Scottish ‘hard man’ Andrew Bonar Law as Conservative leader. Alfred had tried to persuade his party to avoid conflict. Although he had supported Law for the leadership, once it was clear that Balfour had no stomach for the fight, politics could no longer be an adventure shared by friends.

If the political crisis of 1909 onwards dispirited the Lyttelton family, it reinvigorated the Cecils. Bobbety – ‘a ridiculous name but the one by which I am known to my friends’ – Cranborne grew up in a house full of ‘die-hards’ fighting the good fight for their family and class.12 The dominating figure of his early years was his grandfather, the 3rd Marquess. By his exertions Lord Salisbury had lifted the Cecils of Hatfield from centuries spent as political ciphers back to the heights of power they had enjoyed at the turn of the sixteenth century. He was in all ways an awe-inspiring figure, luxuriantly bearded, of huge stature, lapidary judgement and, in the outside world, prime minister until his retirement in 1902, when Bobbety was nine years old. The Cecils were by then the nearest Britain possessed to an imperial family.

Although Lord Salisbury himself had had to struggle hard and rise through his talents, once he reached the pinnacle he buttressed his rule by employing members of his own family. Although he had to look to his sister’s son Balfour as a political lieutenant and eventual successor, three of Salisbury’s five sons also entered politics: the eldest and his heir, Jim (or Jem), Bobbety’s father, and two younger brothers, Lord Robert and Lord Hugh, known as Linkie. It was said of the Cecil boys that ‘their ability varies inversely with their age’. Jim was thus regarded as the least talented, Hugh as the most. By the time Bobbety was old enough to take an interest in the public lives of his father and uncles, the rolling political salons that were Hatfield and Salisbury House in Arlington Street had become his homes. Yet the memory of the great 3rd Marquess still cast a long shadow. Not only did outsiders persistently compare him to his sons, to their perpetual disadvantage, but they themselves were prey to deep feelings of inadequacy. Since 1883 Jim Salisbury had suffered from periodic bouts of depression brought on by ‘these festering feelings of failure’.13

If Oliver Lyttelton grew up in awe of his father, Bobbety grew up in a household of men in awe of his grandfather’s dominating presence. This perhaps contributed to the family traits of fierce pride in the gens, intractability and odd diffidence. On the other hand, the dominant figure in his early life was not his father but his mother, Alice, the daughter of an Irish peer, whom James Cranborne had married in 1887. Although not a public figure as her friend Didi Lyttelton became after her husband’s death, Alice Salisbury was the undisputed chatelaine of Hatfield. She had no compunction about dabbling in politics: she made herself instrumental in the downfall of the Viceroy of India, George Curzon, by acting as the ‘back channel’ between his enemies and Balfour. More than her secret interest in political affairs, however, she provided the social flair and taste for entertaining on a magnificent scale from which her husband shied. She was to prove, behind the scenes, the mainstay of both her husband and her son.14

Lack of appreciable talent did not stop Lord Salisbury raising his son to ministerial rank as under-secretary of state for foreign affairs in 1900. Quips about Cecil nepotism struck and stuck because they were so obviously true. To nobody’s surprise, least of all his own one suspects, Jim Cranborne was not a success in his performance as a Foreign Office minister. He was not impressive in the House of Commons, never having got over his nervousness at speaking. He was thus ‘forbidden to give answers to supplementary questions’ in case he said something damaging. Unfortunately, since he did not have the parliamentary skill of avoiding a question by saying nothing at length, he simply refused to respond to any inquiry that had not been properly notified in advance and for which he had no clear brief. This procedure caused ire and mirth in the House in equal measure. There was soon in existence ‘a universal belief in Jim Cranborne’s complete and invincible incompetence’.15

In the short term, matters did not seem set to improve. In 1903 Lord Salisbury died and Jim Cranborne succeeded him, becoming the 4th Marquess. His translation to the Upper House was a blessed relief. He felt more at home among men who were literally his peers; he was accorded the respect to which his position in society entitled him, with none of the rowdyism of the demotic Commons. His cousin Balfour brought him into the Cabinet as Lord Privy Seal at the same time as Alfred Lyttelton became colonial secretary in October 1903.

As Jim Salisbury was entering into his inheritance, the Conservative party started to tear itself to pieces over the issue of Tariff Reform, the campaign launched by Joseph Chamberlain in May 1903 to convert the party from laissez-faire to protectionism. Chamberlain hit on a sore point. The party had nearly destroyed itself over the issue of Free Trade in the 1840s, had condemned itself to a generation of political impotence and had only fully re-established itself as the natural party of government under Jim’s father. The Cecils were avowed Free Traders, yet the manner in which they prosecuted their campaign did not initially enhance their reputation.

Immediately after the crushing election defeat of 1906, Salisbury circularized all Unionist MPs in order to identify them as Free Traders or Tariff Reformers, or ‘food taxers’ as he called them. The move did not receive a warm response. ‘I am bound to say,’ wrote Lord Balcarres, ‘that I resent this catechism from one whose incompetence has been a contributory cause to our disaster. Good fellow as [ Jim] is, his tact is not generally visible: and it would not be unfair to reply that the taxation of food has doubtless injured the Party – though we have suffered largely from nepotism, sacerdotalism, and inefficiency.’16 Lord Robert and Lord Hugh were on the wilder fringes of the party, locked into spiteful conflict with their constituency parties.17

Like Alfred Lyttelton, Jim Salisbury found the inevitable squabbling in a party forced humiliatingly into opposition after years of rule disheartening. Unlike Lyttelton, he subsequently found a great cause and a method of prosecuting it to call his own. The cause was the House of Lords and the method was obstructionism. The method, it is true, predated the cause. In 1908 one of his colleagues recorded that ‘Jem wanted a guerrilla war with the House of Commons’.18 Jim Salisbury had little talent for constructive political achievement, but he found himself to have a genius for saying no. In 1910, for the first time, he became one of the most important men in the party. It was he who convened the meeting of party grandees at Hatfield in December that forced on Balfour far-reaching changes to party organization. He found willing allies in his brothers. It was Lord Hugh Cecil who led his ‘Hughligans’, a band of about thirty MPs dedicated to howling down Asquith and the Liberal leaders and disrupting the House of Commons. George Wyndham, Oliver Lyttelton’s favourite among his father’s circle, drew the memorable distinction between ‘Ditchers’, ‘those who would the in the last ditch’, and ‘Hedgers’, who were ‘liable to trimming’.19 Lord Salisbury found life much more comfortable once he became a committed Ditcher. In 1905, on the grounds that one should not let mere politics interfere with civilized life, he had had Asquith to dine at Hatfield within twenty-four hours of his cousin and chief Balfour’s resignation as prime minister. In July 1911, the same month in which his brother decided to shout Asquith down in the House of Commons, ‘Lord and Lady Salisbury refused the invitation of the Asquiths to dine at the party given to the King and Queen’. Even Salisbury’s fiercest detractors in the party approved: ‘Asquith and his colleagues are out for blood. He has poured insult and contumely on the peers: why break bread or uncork champagne at his table?’20

The passing of the 1911 Parliament Act by the Liberals under the threat that the new king, George V, would be obliged to swamp the Lords with new peers, was a crushing blow. ‘Politics are beastly’, was Salisbury’s comment. Yet the Act guaranteed the House very considerable powers of delay while Liberal dependence on the Irish nationalists gave the peers a much greater excuse for using those powers than they had had for wrecking Liberal social legislation. Many peers were demoralized by their defeat, but Jim Salisbury was suffused in a glow of moral righteousness. Thereafter he never entirely lost his reputation as the keeper of the true flame of Conservatism. This made him a powerful man, though he was not always comfortable with the role. After the war he confided to his son that he found continual calls to save the Conservative party tiresome. One should remember, he told Bobbety, that parties came and went: principles and family were much more durable.

Bobbety Cranborne and Oliver Lyttelton were brought up at the apex of English social and political life. Politics was the constant backdrop to their childhood. To have Cabinet ministers, even prime ministers, in the house was a regular occurrence. From an early age they were aware of the fascination of politics, but also became youthfully cynical about it. Harry Crookshank and Harold Macmillan did not have such easy access to the political élite. Whereas Cranborne and Lyttelton could see the casualties of ambition – the burnt-out drunks like George Wyndham – ambition for the Crookshank and Macmillan families was entirely positive. It was also more impersonal and structured than for the aristocrats. From the start the course was clear: a forcing prep school, leading to a scholarship at Eton, leading in turn to the best colleges at Oxford. The perfectly respectable schools and colleges attended by their fathers simply would not do.

Although the Macmillan and Crookshank pères followed quite different professions, they had arrived at a remarkably similar social location by the time their sons were born. Harry Maule Crookshank was a doctor who had taken advantage of the expansion of the Empire in the last quarter of the nineteenth century to become an imperial administrator. He came from an old Ulster Protestant family of some distinction. The Crookshanks had arrived in Ulster as part of the seventeenth-century plantation of Scottish Protestants. The family took great pride in their most famous ancestor, William Crookshank, who had been one of the thirteen men who shut the gates of Derry in 1688. Since then the family could boast a brace of Ulster MPs. By the nineteenth century, however, Harry Maule Crookshank’s father and grandfather were making their way through soldiering. Both served as officers in line infantry regiments. Before the Cardwell reforms of the 1870s, officers in the British army purchased their rank. The Crookshanks thus had some funds behind them but could not rise to great heights. Harry Maule’s grandfather finished his career as a colonel. His father was a captain at the time of his early death while serving in India. While overseas Harry Maule was to send his son, Harry Comfort, for his initial education in Europe. This seems to have been part of a family pattern, for he himself received his early education in Boulogne before proceeding to a minor public school in Cheltenham. He was not destined for the army but instead studied medicine at University College Hospital, London. Although Crookshank had not joined the British army, he maintained his family’s military tradition. At the age of twenty-one he joined a Red Cross ambulance unit serving in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. He repeated the experience later in the decade, joining a similar unit in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–8. Crookshank’s contact with the Ottoman Empire brought about a fundamental change in his life. In 1882 British forces invaded Egypt to secure the recently completed Suez Canal. Following in the wake of the troops were British officials dedicated to the reform of the corrupt and ineffectual Egyptian state. Between 1883 and 1914 the real power in Egypt lay with the British, led by Lord Cromer.

Harry Maule Crookshank found himself an important cog in Cromer’s machine as director-general of the Egyptian Prisons Administration. Coming from an undistinguished background he was, at the age of thirty-four, relatively young for his responsibilities. In 1883 Crookshank faced a difficult situation. The British regarded the Egyptian prisons they found as utterly barbarous and in urgent need of reform. ‘No report,’ wrote the author of the initial survey of the system, ‘can convey the feeblest impression of the helpless misery of the prisoners, who live for months like wild beasts, without change of clothing, half-starved, ignorant of the fate of their families and bewailing their own.’ The problem of the prisons was part of a wider malaise in a justice system dominated ‘by venality, tyranny and personal vindictiveness’.21 Yet British officials were being somewhat disingenuous in their criticism of the existing Egyptian prison system. The first concern for Cromer’s new administration was not reforming the prisons but bringing Egypt under its own firm control. To this end the 1880s were marked by a system akin to martial law. ‘Brigandage commissions’ ensured that as many potential troublemakers as possible were imprisoned. The combination of Egyptian inefficiency and British efficiency meant that there was massive overcrowding in the prisons: the gaols were at four times their nominal capacity.22

Crookshank’s eventual reform programme followed four main lines: old prisons were improved and made sanitary, new prisons were built, prisoners were provided with proper food and clothing and a separate system of reformatories for young offenders was created. The work was long, arduous and not always rewarding. Since the criminal justice system formed the keystone of ‘indirect’ rule, its conduct was the matter of much debate, even conflict, among the British themselves. Crookshank became involved on the side of those pragmatists who believed that as much use as possible should be made of the existing Egyptian system, already reformed on French lines before the occupation. His chief opponent was Sir Benson Maxwell, a naturally disputatious man who served as first procureur-général and believed the system should be purged of any intermediary foreign taint and thoroughly anglicized on the colonial model. Money was always tight. As Lord Cromer recorded in 1907, the year Crookshank left Egypt, ‘These reforms took time: Even now the prison accommodation can scarcely be said to be adequate to meet all the requirements of the country.’ Crookshank’s successor as director-general, Charles Coles, who took over in 1897, had a police rather than a medical background. He implied that his predecessor had been too soft. It was arguable, Coles felt, ‘that prison life is not sufficiently deterrent, and that the swing of the pendulum has carried the Administration too far in the direction of humanity, if not of luxury’.

There is no record of how the Crookshanks felt when Cromer gave credit to Coles rather than Harry Maule as the man ‘to whom the credit of reforming this branch of the Public Service is mainly due’. It was not in Harry Maule’s nature to push himself forward. Indeed, Coles felt that Crookshank had been unnecessarily diffident in his dealings with Cromer.23 It would seem even so that Crookshank’s performance in fourteen years of overseeing the prisons was rated highly enough for him to be given another important and far more agreeable job within the administration. In 1897 he was made controller of the Daira Sanieh Administration. The Daira estates were lands that the former ruler of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, had ‘contrived, generally by illicit and arbitrary methods, to accumulate in his own hands’. By the time the British arrived they amounted to over half a million acres. They were, however, very heavily mortgaged. When the profligate Ismail had got into severe financial difficulties he had borrowed £9.5 million on the security of the properties.

Under the Cromer regime the estates were run in the manner that became standard practice: giving the appearance of authority to Egyptians but severely trammelling their power. The putative administrator of the lands was an Egyptian director-general, but he was joined on a board of directors by two controllers, one British, the post Crookshank took on, and one French. The controllers ‘had ample powers of supervision and inspection. They alone were the legal representatives of the bondholders.’ Cromer regarded Crookshank’s performance as British controller as admirable. The main problem for the board was that the estates were so heavily indebted that expenditure on loan repayments always outran revenue. The first step, taken before Crookshank’s time, was to extract higher revenues from the estates.

From 1892 onwards, the properties started to yield a profit, though there was a brief crisis in 1895 not long before Crookshank’s arrival. By Crookshank’s last years in office, revenue was very healthy indeed, amounting to over £800,000 in 1904–5. Under Crookshank, however, a new policy was instituted. Cromer had close relations with the banker Ernest Cassel. Cassel thought that a great deal of money could be made from the estates. In 1898 the estates were made over to a new company charged with selling them off in lots. By the time Crookshank demitted office, all the lots had been sold, yielding a net profit for the government of over £3.25 million.24 Crookshank was leaving at a good time. When Cromer retired, the speculation in Egyptian land and shares in which Crookshank had been a pivotal figure rebounded into a financial crisis. Cromer’s successor, Eldon Gorst, concluded that the relationship between financiers and Cromer’s apparat had been rather too close for comfort. Profit had not necessarily walked hand in hand with good governance.25 Crookshank slipped into comfortable retirement in the wake of his master. He had been a faithful and discreet servant.

In later life Harry Crookshank was proud of and interested in his father’s official career. He too was to serve as an official in what was by then the former Ottoman Empire. He planned to make Egypt and Turkey his areas of particular expertise when he first entered the House of Commons, though these plans went awry. In many ways it was the position that Harry Maule’s achievements gave him in society that shaped Harry Comfort’s world. In 1890, at the mid-point of his term in the prison administration, Harry Crookshank was accorded the honorific ‘Pasha’. It was as Crookshank Pasha that he was known thereafter. Although his job had not changed, the oriental glamour of his new status helped him to woo a young Vassar-educated American visitor to Egypt, Emma Walraven Comfort.

Crookshank’s marriage to Emma Comfort in 1891 was wholly advantageous. Her father, Samuel Comfort, was one of the founders of Standard Oil, the company created by his contemporary John D. Rockefeller in 1870. By the end the 1870s Standard Oil had come to control the entire American oil market. In 1882 its owners created the ‘Trust’: at the time Crookshank met Emma the conflict between Standard and the ‘trustbusters’ was one of the most important struggles in American political life. Samuel Comfort was a ‘robber baron’ of the ‘Gilded Age’.26 He was rich and Emma was his only daughter. When Harry Comfort Crookshank was born in 1893, his way of life had already been determined. He would never have to work for a living. Money would continue to flow in from the most ‘blue chip’ stocks and shares imaginable, given to or inherited by his mother.

One of Crookshank Pasha’s enthusiasms had a profound effect on his son’s life. In his annus mirabilis of 1891, Harry Maule Crookshank was installed in the Grecia Lodge in Cairo. The lodge’s best-known member was Kitchener, who became master the year after Crookshank joined.27 Like his father Harry Comfort was to be a passionate Freemason. He joined the Apollo Lodge as soon as he arrived in Oxford in 1912, the earliest possible opportunity. His attachment to Freemasonry thus predated his political ambitions. He would pursue his Masonic career with as much enthusiasm and ambition as he embraced Parliament.

Crookshank spent his early childhood in Cairo, but in 1903 he was sent to school in Lausanne.28 In May 1904 he arrived at Summer Fields, a prep school at Oxford, to find Harold Macmillan already installed. Macmillan’s road to Summer Fields had been much less exotic. His father, Maurice, had after a few years schoolmastering joined the family publishing firm. On a trip to Paris he met a young American widow, Nellie Hill. Nellie was the daughter of a Methodist preacher in Indiana. At the age of eighteen she had married into a well-to-do family in Indianapolis. Her husband survived only five months of marriage. Using the money he left her, Nellie decamped for Europe in the late 1870s. She had no fondness for the American Midwest and was happy to move to England with Maurice when they married in 1884. Unlike his new friend Harry Crookshank, Harold was a late child, born ten years later when his mother was forty. By then the family was firmly established in a tall, narrow house in Cadogan Place, the connecting link ‘between the aristocratic pavements of Belgrave Square and the barbarism of Chelsea’. There was also a substantial if inelegant country house in Sussex, Birch Grove.

In contrast to the Crookshanks, where the mother’s wealth was paramount, it was Maurice Macmillan who financed the family’s lifestyle. Yet there was no doubt that the ‘master of the house’ was the dominant figure of Nellie Macmillan. Mrs Macmillan threw herself with gusto into the public life of her adopted country. Her milieu was the societies of rich and well-connected ladies devoted to some public cause. Her main efforts were expended on the Victoria League, a body of imperial enthusiasts founded in memory of the recently deceased Queen-Empress, of which, for many years, she was honorary treasurer. She became acquainted with her fellow American imperial enthusiast Emma Crookshank.

For both the Macmillans and the Crookshanks to send a son to Summer Fields was a clear declaration of intent. The establishment had been created so that its pupils could compete for scholarships to the major public schools. Between 1897 and 1916 the school averaged more than five Eton scholarships a year. By the time Macmillan and Crookshank reached College, one in three of their fellow scholars had been to Summer Fields.29 As Henry Willink, who scraped into the same election at Eton as Macmillan and Crookshank, recalled: ‘I had not been skilfully prepared for the Scholarship examination as…boys at Summer Fields were prepared.’30 ‘If,’ as the school history puts it, ‘the boys were not force-fed they were certainly stuffed.’ Summer Fields, where Macmillan and Crookshank became close friends, duly delivered on its promises. Both boys were placed on the list of seventeen that made up the Eton election of 1906.

Eton in 1906 was undoubtedly the most famous and prestigious school in England.31 It was also in many ways the perfect microcosm of the social universe represented by Macmillan and Crookshank on the one hand and Lyttelton and Cranborne on the other. Eton was divided into two unequal parts. In College there were a total of seventy scholars, ‘Collegers’, or ‘Tugs’. Entrance was by the fiercely competitive examination Macmillan and Crookshank had just sat. As a result College was dominated by boys just like them: from families dedicated to the late Victorian cult of achievement through hard work.

There were a much larger number of boys in School, the Oppidans. The year 1906 was a bumper one for School, with 224 new boys, of whom Cranborne and Lyttelton were two. School was of distinctly mixed ability, entrance being governed by family tradition and contacts. As Oliver Lyttelton observed, the masters ‘were inclined to be slightly snobbish…they conceived their role in the State to be that of training and teaching those who were likely to shape its future [and thus]…wanted to have pupils from the great families. The sons of those families would have a start in the race.’32 Initially the Collegers and Oppidans, further divided into their boarding houses, were kept fairly separate. As they progressed through the school there would be more mixing, particularly as they shared the pupil rooms of the Classical Tutors. Lyttelton and Cranborne were members of Henry Bowlby’s house and mixed with Macmillan and Crookshank in his pupil room. It was exactly this mixing that attracted ambitious families to Eton.

The Eton the four boys attended was, on the surface, in a process of dynamic expansion. The school was nevertheless plagued with troubling undercurrents. In 1905 the long headmastership of Dr Warre came to an end. Warre had instituted an extensive building programme completed while the boys were at Eton: the gymnasium was opened in 1907, the hall in 1908 and the library in 1910. Although the fruit of previous expenditure was in the process of realization, the school was thus in a period of financial retrenchment. Warre’s departure also opened the way for a power struggle between his presumed successor, A. C. Benson, a brilliant but depressive homosexual, and the leader of the younger ‘Classics’, the acerbic A. B. Ramsay, known as ‘the Ram’. The most powerful voice on the selection panel, Lord Cobham, was able to usher in his kinsman, Edward Lyttelton, as a compromise candidate.

Oliver Lyttelton was thus faced with every schoolboy’s nightmare – a close relative as headmaster. He was frequently mortified by his uncle’s tendency to trumpet the moral superiority of the Lytteltons – which he later described as ‘washing clean linen in public’. Lyttelton’s embarrassment was accentuated by Uncle Edward’s undoubted peculiarities. No one doubted that he was a perfect Christian gentleman and a fine sportsman, but he was an indifferent classicist and soon became the butt of Collegers whose grasp of Latin far exceeded his own. He was also a health faddist, following a vegetarian diet and lauding the virtues of outdoor living. His healthy tan earned him the nickname ‘the Brown Man’ in an age that valued alabaster complexions. The headmaster’s attempts to keep in check the tendency of Etonians to lord it over the neighbouring population won him few friends in the school and met with limited success. Lyttelton failed to persuade the Master and Fellows to broaden the curriculum at the expense of an unleavened diet of literary classics. The boys, as so often, were dyed-in-the-wool reactionaries when it came to such matters. Macmillan angrily noted: ‘I am rather annoyed at the nonsense that people are talking and writing about “Education”…we are all to learn, it seems, about stocks and shares. Instead of humanities we are to dissect frogs and make horrible smells in expensive laboratories…I do not see that an ignorance of chemistry is any better than an ignorance of Classics.’33 Edward Lyttelton’s career at Eton was ended during the war by a brave if – given the temper of the times – unwise speech proposing that Britain should cede Gibraltar to Germany in return for peace.

Each of the boys had a rather different experience of Eton. Of the four Lyttelton’s is by far the best recorded. The main challenge he faced was the long shadow cast by his father’s glittering reputation at Eton. His solid school career was always found wanting when set next to that of Alfred. He worked hard at everything, becoming house captain of Lubbock’s and achieving entrance to the Classical First where the best scholars, whether Colleger or Oppidan, were taught together. Success had its drawbacks: ‘Everything is rather an ordeal at present,’ he reported home, ‘I mean I am always finding myself in solitary positions of responsibility; either I am leading sixth form into chapel or I am making a speech or I am commanding the company in the Corps or I am president of the debate but I am getting used to them all.’34 Of some importance for the future, he did plenty of soldiering.35 His housemaster, Samuel Lubbock, who had taken the house over from Bowlby when the latter left to become headmaster of Lancing, noticed his efforts with pleasure: ‘He deserves the best report I can give him,’ he wrote to Alfred, ‘certainly the house will never have a better captain…His work has improved to a far greater [extent] than a year ago I thought probable and his marks in trials are quite encouraging.’36 Lubbock also made the rather rash prediction that ‘with really hard work he might just be up to a First at Cambridge’: he subsequently had to admit that his enthusiasm for Oliver’s personality had led him to overestimate his scholarly abilities.

Most pleasing of all, Oliver was finally elected to Eton’s self-selecting elite of senior boys, the Eton Society or ‘Pop’, of which, inevitably, his father had been president, in his final half. It had been a struggle to ingratiate himself. His election, Lubbock reported, ‘does credit to Pop: for great and sound as his merits are, he is rather too clever and too old [for] many average boys: as I have said before he jests rather too frequently and they don’t quite understand all his jokes…and boys are very self-conscious creatures. But he is quick at seeing things and I think he has seen this clearly enough.’37 Unfortunately Lubbock was rather too sanguine on the last point. Three years later Raymond Asquith reported from the trenches that ‘his chief defect to my mind is one inherited from Alfred – telling rather long and moderately good stories and laughing hysterically long before he comes to the point’.38 Fifty-two years later, a former Cabinet colleague wrote that Lyttelton’s sense of humour ‘varied from classical to Rabelaisian or even third form…The only difficulty was that an immediate appreciation of the humorous aspects of any question was inclined to limit the expression of the arguments in mundane terms.’39

It was towards the end of their time at Eton that Oliver and Bobbety became close friends. For many Oppidans there was no presumption that they would go on to university; many drifted away to join the army or to travel on the Continent as a means of finishing their education. Lyttelton bemoaned the fact that by 1910 ‘all my particular pals will be gone except Cranborne’.40 From then on the two started messing together.41

Fifty years on Osbert Sitwell reminded Bobbety ‘that you were a studious small boy’.42 Yet if his scholarly performance was anything to go by, the school inspectors who visited Eton in 1910 might have been thinking of Cranborne when they wrote in their report: ‘we do not forget that Eton’s highest service to the nation is that she educates boys whose circumstances make it difficult or impossible for the school work to be as important in their eyes as it is in the eyes of less fortunate schoolboys’. The main strength of the Eton education was languages and Cranborne left School in 1911 with no firm grasp of any, whether classical or modern.

In College meanwhile Crookshank made good progress. His main problem was a complete lack of sporting prowess. Even Macmillan, a self-confessed duffer at games, was picked for the College team that played the Oppidans at the uniquely Etonian form of football known as the Wall Game. Crookshank was no more than an ardent admirer of those who could play. The Daily Graphic printed a picture of him among the crowd carrying the Collegers’ wall keeper in triumph after College had defeated the School. ‘It is dreadful,’ he lamented in 1917, while serving in Salonika, ‘this is the first Wall Match I have missed since I first went to Eton in 1906. I suppose it had to come some time, but it is rather a bitter blow.’43 Apart from his deficiency in games he excelled in most other areas. He was good at his work, was a fine debater, edited the school magazine and was elected to Pop with rather more ease than Lyttelton. In their final year these two found themselves thrown together quite regularly. They studied classics together, with Crookshank consistently near the top of the class, Lyttelton consistently near the bottom.44 At their final speech day in June 1912, Lyttelton gave a reading from the essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ by de Quincey, Crookshank from Lincoln’s second inaugural. They performed together in a sketch adapted from the Pickwick Papers: Crookshank taking the part of Mr Phunky, Lyttelton of Sam Weller.45

By the time Cranborne, Lyttelton and Crookshank were forming their mature friendships at school, they were no longer boys but young men. The notable absentee was, of course, Macmillan, who was the only one who crashed at Eton. Macmillan and Crookshank had maintained their Summer Fields friendship. Whereas Crookshank flowered at Eton, Macmillan struggled. He was withdrawn by his mother in 1909. Macmillan was tight-lipped about his failure. He devoted a page in his memoirs to Eton as compared to a full chapter in Lyttelton’s. By his own account: ‘During my first half at Eton I had a serious attack of pneumonia, which I only just survived. Some years later, I suffered from growing too fast, and a bad state of the heart was diagnosed. This led to my leaving Eton prematurely and spending many months in bed or as an invalid.’46 Many years later J. B. S. Haldane spread the rumour that Macmillan had, in fact, been expelled for egregious homosexuality. Eton, like all public schools, lived in fear of the nameless vice. One of Edward Lyttelton’s first acts as headmaster was to break a house whose captain had an appetite for buggery. Haldane was certainly in a position to know the cause of Macmillan’s departure. ‘Of course I remember him very well,’ Macmillan acknowledged when he was prime minister. ‘He was in the election above me at College, as well as a pupil of Henry Bowlby. I used to see him after the first war but have not seen him for many years.’47 Haldane was, in all likelihood, motivated by malice. Macmillan himself was certainly malicious about Haldane’s family. Enjoying the discomfiture of Gilbert Mitchison in the House of Commons, his mind was thrown back to Eton. ‘He was Captain of Oppidans in my time and was a silly, pompous and conceited ass even then. As a punishment he married Naomi Haldane, and is now more or less insane.’48 Whatever the truth about Macmillan’s departure from Eton, it certainly denied him the opportunity to mix with boys of his own age at the very time when he was maturing into manhood. This was to presage an unfortunate pattern. His time at Oxford was also cut short, as was his time in the army. Throughout his life Macmillan was to have difficulties in his relations with male contemporaries. The one relationship in which there was never awkwardness was that with Harry Crookshank. That they had been friends even before they reached Eton was significant.

Macmillan returned home from Eton to an even more pressurized environment. A. B. Ramsay, the fearsome Classic, called regularly to give him lessons. He seemed to Macmillan ‘a man of the world, elegant, refined and a most perfect gentleman’, much superior to Dr Lyttelton.49 His mother’s other choices of tutor were somewhat stranger. The first to arrive was a Dilly Knox, friend of Harold’s brother, Daniel. On the face of it, the Knox connection seemed safe enough. Knox père was the fiercely evangelical Bishop of Manchester, known as ‘Hard Knox’ for his no-nonsense approach to educating the young.50 Dilly Knox, on the other hand, was one of those young masters who took the lead in ragging Edward Lyttelton. Knox was a formidable classical scholar but was found too ‘austere’ for Harold. He was replaced by his younger brother Ronnie. Dilly was eleven years older than Harold, whereas Ronnie was only six years his senior. Harold was seventeen, Ronnie twenty-two: they were close enough in age to become intimate friends. Too intimate, in the view of Nellie Macmillan. She ordered Ronnie from the house in 1910. They had already argued about his pay, but this was ‘7000 times more important’. Mrs Macmillan had accused Ronnie of infecting Harold with ‘papism’. The situation was fraught with emotion: ‘I am extremely (and not unreturnedly) fond of the boy,’ Ronnie told his sister, ‘and it’s been a horrid wrench to go without saying a word to him of what I wanted to say.’51 Whatever its dangers, Harold’s high-priced and exceptional tuition did pay off in one sense: he won an Exhibition to Balliol and was thus able to arrive at university at the same time as his Eton contemporaries.

Just as Eton was not just another public school, so the colleges the boys attended at Oxford and Cambridge were notable for their wealth, size and social prestige. Lyttelton and Cranborne could simply follow in family tradition, Lyttelton to Trinity College, Cambridge, Cranborne to Christ Church, Oxford. Family tradition meant nothing to the new men. Crookshank went up to Magdalen College, Oxford, Macmillan followed his brother to the worldly Balliol College, Oxford, rather than his father to the more ascetic Christ’s College, Cambridge.

The traditional patterns established at Eton persisted at university. Lyttelton and Cranborne gravitated to the aristocratic beau monde, giving little thought to their studies. Macmillan and Crookshank were exceptionally serious. Lyttelton quickly discovered the joy of girls. In the Easter vacation of his first year he found himself staying at Lympne Castle, not far from Wittersham, with ‘Dinah’. He regaled his mother with their adventures: ‘Dinah and I…set off to walk to Lympne. After half an hour Dinah fell into a ditch and got wet and being anxious to see me in the same state made a compact with me that we wouldn’t go round any canal. Soon we swam a broad canal having thrown most of our clothes over the other side and we ended up swimming the military canal.’52 He drew a discreet veil over the denouement of their unclothed adventures in the Royal Military Canal. He also abjured his parents’ distaste for horse racing. Lyttelton’s passion for gambling led to inevitable conflicts, unconvincing excuses and anguished reconciliations when he had to borrow money from his parents to settle his debts:

I am so terribly sorry that you should have thought I was ungrateful or anything, that I don’t know what to do. But for the last three days I have been ill, I eat [sic] something that has poisoned me, and I have been bad and very sick but am better today. I am clearing up my accounts and will write you tomorrow at the latest. Darling Mother, for God’s sake don’t think me ungrateful for I simply can’t stand it. I have done ill enough without this: but that you should think me ungrateful or callous is too awful. You can’t realize how I feel towards you both or you couldn’t think such a thing for a minute. So please understand, I am sure you do really.53

Bobbety Cranborne had no such money worries. His set at Oxford consisted of aristocrats, both English and foreign, as well as royalty. He roomed with the Russian prince Serge Obolensky, whom Lyttelton found ‘rather nice and very good looking’.54 Unlike Obolensky, who was a fanatical polo player, Cranborne was not particularly horsy. This did not prevent him living a ‘hearty’ lifestyle. He was a member of the Loders Club, where a requirement for membership was that one was ‘a gentleman, a sportsman, and a jolly good fellow’. Established in 1814 as a debating club, it had long since degenerated into a group that dedicated each Sunday in term to hard drinking. In a mockery of the Oxford-Cambridge polo match, in which Obolensky was playing ‘at some unearthly inappropriate hour’, Bobbety and Prince Paul of Yugoslavia ‘got bicycles and awakened the echoes by playing polo in the street’. When they were arrested, a drunken Cranborne declared that he needed no lawyer and would defend in person the right of freeborn Englishmen to play bicycle polo. In court he ‘said he did not think they had annoyed any of the residents, but had merely entertained them’. For all his pains, they were fined a crown each and costs.55

Cranborne’s academic performance was abject. In his first year he failed in his attempts to avoid his matriculation examination.56 In 1913 he failed his Mods completely, drawing ‘sympathy…qualified by remonstrance and admonition’ from his tutor.57 He decided that he would not bother to try again. In any case, of much more long-term moment than a failure to grapple with the classical authors was his burgeoning interest in international affairs.58 He became close friends with Timothy Eden, ‘a shy, retiring, soft-featured young man’ who was the heir to a baronetcy.59 Eden was part of the more ‘worthy’ side of Cranborne’s Oxford life.60 He ran a ‘Round Table’ devoted to public affairs. He made contact with serious-minded young men like Frank Walters, who later became an official and champion of the League of Nations.61 Through his uncles, both outspoken champions of Anglo-Catholicism, Cranborne also got to know Macmillan’s mentor Ronnie Knox whom he invited to his eponymous country seat, Cranborne in Dorset, during the Easter vacation of 1914.

In 1912 Cranborne’s father decided that he should be sent to South Africa with his prospective brother-in-law, a precocious if pompous MP in his twenties, Billy Ormsby-Gore.62 The choice was important for the future. Most undergraduates tended to travel to France or Germany in the summers to improve their languages. Macmillan went on a reading party to Austria in 1913, Lyttelton ‘studied French in a small house in Fontainebleau, where the food did not live up to French standards’. Crookshank was in Germany with four friends during the summer of 1914 and barely escaped internment: the certificate of British nationality that enabled him to flee was stamped by the British consul in Hanover as late as 31 July. Indeed, Cranborne had intended to go to Germany himself in 1913 with Jock Balfour, an Eton friend, but cried off because of ill-health.63 It was a lucky escape. Both Jock Balfour and Timothy Eden returned to Germany the following summer and spent the war in internment. By choice as well as chance Cranborne was caught up by the glamour of the Empire. His trip with Ormsby-Gore, including a return journey up the east coast of Africa and through the Suez Canal, imbued him with an abiding interest in the continent and a love of southern Africa.64

Crookshank and Macmillan took their time at Oxford much more seriously. Crookshank devoted himself to work and Freemasonry. It was thus ‘simply sickening’ when he ‘only just missed’ his First in Mods.65 The problem was fairly plain: he was a good Latinist but much weaker at Greek. Macmillan’s superb tuition enabled him to overtake his friend: he ‘just managed to scrape a First with some difficulty’.66 Macmillan had other strings to his bow. His renewed relationship with Ronnie Knox brought with it a friendship with Knox’s other acolyte, the Wykehamist Guy Lawrence, and gave his life emotional intensity. ‘It is hard to give a definition or even a description of them,’ Ronnie wrote of the pair in 1917, ‘except perhaps to say that in a rather varied experience I have never met conversation so brilliant – with the brilliance of humour not wit.’ Macmillan and Lawrence ‘had already adopted what I heard (and shuddered to hear) described as “Ronnie’s religion”’. Indeed, serving Ronnie at Mass was a regular element of Macmillan’s Oxford experience.

Knox is often described as leading Lawrence and Macmillan towards Rome. Although Knox had decided by 1915 that the Church of England was illegitimate, he did not become a Roman Catholic until 1917. In fact it was Guy Lawrence who jumped first. ‘God made it clear to me and I went straight to [the Jesuits at] Farm Street…Come and be happy,’ Lawrence urged Knox. Lawrence believed that ‘Harold will, I think, follow very soon’. Harold did no such thing. He told Knox that he was ‘not going to “Pope” until after the war (if I’m still alive)’. This strange response suggests that Macmillan had little real feeling for the religious issues as Knox and Lawrence felt them. If one came to the realization that Anglican rites and orders, however modified, were a ‘sham jewel’, one risked the immortal soul by dying in error. It seems likely that Macmillan was more excited by the cell’s mixture of incense and intimacy than theology per se. In Trinity term 1914 he was poised between another overseas reading party organized by the don, ‘Sligger’ Urquhart, and Knox and Lawrence’s planned retreat in rural Gloucestershire for the summer vacation. Both promised an intimate atmosphere.

Conversion in any case threatened an irreparable breach with his mother, a dyed-in-the-wool anti-Catholic bigot, exclusion from Macmillan money and thus an end to worldly ambition. Macmillan had the sort of open ambition that is displayed by running for office in the Union. In May 1913 he made ‘the best speech we have heard this year from a Freshman’. Returning at the beginning of the next academic year, he made ‘an exceedingly brilliant speech, witty, powerful and at moments eloquent’. He was elected secretary in 1913 and treasurer in 1914. Having held the two junior posts in the triumvirate at the head of the Union, he would still have had time to run for president before the end of his undergraduate career. It is perhaps revealing that his star-struck younger friend Bimbo Tennant believed he had been president of the Union.67

Whereas Macmillan’s second year at university was filled with excitement and expanding horizons, that of Lyttelton and Crookshank was blighted by the deaths of their fathers in July 1913 and March 1914 respectively. While the Crookshanks’ grief was private, the Lytteltons’ was all too public. The golden good fortune that had always followed Alfred Lyttelton was brought to an abrupt end at a time when he seemed to have hit a good seam in politics. At least one knowledgeable observer noted that the kind of business coming before the House in 1913 suited his style. On plans to disestablish the Church of Wales and attempts to hold government ministers to account for their corrupt personal involvement in the ‘Marconi scandal’ ‘he had lately made some good speeches. His extreme moderation gave extra effect to any attack that did come from him.’68 As Oliver put it, ‘I feel the political situation is improving for Dada.’69

The best gentleman cricketer of his generation was felled by a ball bowled by a professional fast bowler in a charity match. Incompetently treated, he died from acute peritonitis a few days later. The prime minister, Asquith, delivered his encomium in the House of Commons. ‘I hardly trust myself to speak,’ he told the House, ‘for, apart from ties of relationship, there had subsisted between us thirty-three years of close friendship and affection.’ Asquith’s oratory rose to the occasion as he famously memorialized his friend as the one who ‘perhaps of all men of this generation, came nearest to the mould and ideal of manhood, which every English father would like to see his son aspire to, and if possible attain’. Thus another heavy burden was laid on Oliver: to be the son of the man who was the perfect son. Fifty years later he would still feel ‘acutely how far short of the example which I was set’ he had fallen. Even in an age of numberless tragedies, those that struck some individuals most grievously were coeval to the war but entirely unrelated to it.

If the celebrity accorded their fathers differed, so too did the private circumstances of Crookshank and Lyttelton. The removal of Crookshank Pasha made no material difference to his family since it was from his wife that his wealth stemmed. There was now created the ménage that would sustain Crookshank for most of the rest of his life. His sister and his mother ministered to his every need, cared for him physically and sustained him emotionally until their deaths in 1948 and 1954 respectively. The Crookshanks’ initial London base was in Queen Anne’s Mansions, a fourteen-storey apartment block that had just been built, ‘without any external decoration…for real ugliness unsurpassed by any other great building in all London’. In 1937 they moved to 51 Pont Street. Visiting them there just after the outbreak of the Second World War, the politician Cuthbert Headlam found ‘the Crookshanks mère fils et fille exactly the same as ever – the women garrulous, Harry as self centred’.70 ‘As you entered through the heavily leaded glass door,’ Harold Macmillan’s brother-in-law remembered, ‘the catacomb like gloom was relieved only by one small weak electric bulb, like the light on the tabernacle “dimly burning”.’ The house was a shrine to the Crookshanks’ life in the 1890s: ‘Eastern objets d’art and uncomfortable Victorian furniture.’71

For Lyttelton the death of his father changed a great deal in his life. Alfred Lyttelton had been a rich man, but his wealth derived mainly from the income he earned not capital he had accumulated. On his deathbed Alfred Lyttelton had commended Oliver to the care of his friend Arthur Balfour. This was a choice based on sentiment or ignorance given Balfour’s spectacular mismanagement of the fortune that he had inherited. It was quite clear that Oliver would have to make his own way in the world. The most obvious way forward was to follow his father into the law: by 1914 he was eating dinners at the Inns of Court and clerking for judges on the circuit.72

Although by the summer of 1914 the future was beginning to be limned, – Lyttleton would be a lawyer, Cranborne would be a lord, Macmillan would be a gentleman publisher – the four were still little more than interested observers of the scene. Their hopes and interests reflected very accurately their position in society. They did not lack talent but none of them was outstanding. If the example of others, grandfathers, fathers and brothers, brought this home to them they nevertheless had a high opinion of themselves. They had a fund of impressions and sometimes inchoate opinions. They were, in a word, undergraduates, and typical of the breed. As Lyttelton himself later put it: ‘At the University I merely became social and an educated flâneur. It was the camp and the Army that turned me into a case-hardened man.’73 The fact that one in four of those who were at Oxford and Cambridge at the same time as this quartet were to be killed in the Great War should not lead us to over-dramatize their pre-war experience. They had not ‘grown up in a society which was half in love with death’. They would have been surprised to have been told that ‘they were afflicted with the romantic fatalism that characterized that apocalyptic age’.74 The picture of a golden but doomed generation is an ex post facto invention.