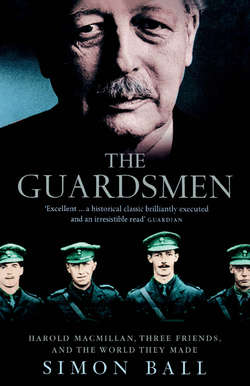

Читать книгу The Guardsmen: Harold Macmillan, Three Friends and the World they Made - Simon Ball - Страница 8

2 Grenadiers

ОглавлениеTo serve in the Guards was to have a very specific experience of the war. They were socially élitist, officered by aristocrats or by those who aspired to be like aristocrats. They were also a combat élite. Robert Graves reported the view that the British army in France was divided into three equal parts: units that were always reliable, units that were usually reliable and unreliable units.1 The Guards were on his ‘always reliable’ list. They were introverted, especially so once an entire Guards division was created in 1915. A junior officer would rarely ever come into contact with a senior officer who was himself not a Guardsman. They had an unshakeable esprit de corps. They were envied by other units. James Stuart, Cranborne and Macmillan’s brother-in-law, who served with the Royal Scots, remembered that ‘the Guards were always regarded by the Regiments of the Line as spoilt darlings’.2

All this mattered. Although the experience of war was one of terrifying loneliness, to succeed one had to be part of a successful team. Seen from a distance, the industrialized slaughter of the Great War seemed to submerge the individual in the mass. Yet this was not the experience of the young officers. The mass was very distant: the platoon, the company, the battalion and especially the battalion officers were the points of reference that mattered. Combatants faced the terror of ‘men against fire’: caught in an artillery barrage or enfiladed by machine-guns, it did not matter whether a man was the best or worst soldier – survival was purely a matter of luck. Yet on other occasions success in close-quarters fighting rested on skill, strength and the will to prevail.

It mattered what one did and with whom. It also mattered when one joined the army. Those undergraduates who volunteered in 1914 reached the front in 1915. Although they were part of the process by which the army transformed itself from a small professional force into a ‘people’s army’, those in the Guards were inoculated against this experience. Many ‘hostilities only’ officers entered the Guards regiments, but ‘dilution’ was strictly limited: the Grenadier Guards had doubled in size from two to four battalions by 1915, but the process went no further for the rest of the war. The new Guards officers were, however, not insulated from the battles of 1915 and 1916. It was in these battles that the army grappled with the problem of how to fight a modern war. It was a bitter experience. Casualties were very high. Nearly 15 per cent of those officers who fought in the battles of 1915 died, nearly one quarter were wounded. Well over one quarter of those who had joined up from Oxford and Cambridge at the start of the war died.3 This cohort’s career as regimental infantry officers was effectively over by the end of the battle of the Somme in 1916.

The horrors of the Western Front were not, as it happened, at the forefront of the minds of four patriotic undergraduates in the first months of the war. Their anxieties were more about their social position in the struggle. Cranborne and Lyttelton had, as usual, a head start because of their connections. Cranborne’s father had a proprietary interest in the 4th Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment, which he himself had taken to South Africa to fight in the Boer War. Salisbury had promised Alfred Lyttelton on his deathbed that he would watch out for Oliver’s interests. He promised to fix commissions for his son and his ward as soon as possible. Little over a week after the outbreak of the war, Lyttelton and Cranborne handed in their applications for a commission.4 Cranborne invited Lyttelton and another friend, Arthur Penn, to Hatfield to await their call-up.5 They whiled away their time with shotguns. The juxtaposition of a shooting party as the preliminary to a war later caused them some grim amusement. Penn, invalided home, having been shot in both legs, wrote up his own game book as, ‘BEAT – Cour de l’Avoué: BAG – Self’.6

Despite Lord Salisbury’s patronage, the trio remained fearful that they would become trapped in the wrong part of the military machine. ‘We are having trouble about our commissions,’ Lyttelton wrote anxiously. ‘The War Office, gazetted six officers, all complete outsiders, yesterday to the Regiment and none of us. The Regiment is furious because they loathe having outsiders naturally, we are angry because it seems possible that we may be gazetted to K[itchener]’s army.’ Salisbury made a personal visit to the War Office and ‘raised hell’.7 The wait was made even more maddening for Lyttelton and Penn by Cranborne’s new-found enthusiasm for playing the mouth organ.8

Salisbury was able to secure commissions for his son and his son’s friends. They joined their regiment at Harwich. It seems the trio had originally intended to stay with the Bedfordshires: Salisbury had hoped that the battalion would be sent overseas as a garrison or to France as a second-echelon formation. This plan was abandoned as soon as it became clear that reserve formations like the Bedfordshire militia would be cannibalized to provide manpower for fighting formations. Cranborne and Lyttelton had ambivalent feelings about not being posted to a line infantry battalion. ‘I am sorry because I must fight,’ Lyttelton wrote, ‘and I am glad…because I should rather dislike going into a regiment – probably a bad one – in which I know no one.’9 On 12 November 1914 their chances of going to France as part of a battalion disappeared: ‘it was the most tragic sight,’ in Lyttelton’s view, ‘seeing three hundred of our best men leaving for the front…without a single officer of their own’.10 Rumours flew around the camp that the battalion would become little more than a training establishment. Lyttelton and Cranborne felt that any obligation they had had to stay with their regiment had been removed. Lord Salisbury had always kept up close links with the Guards, recruiting time-expired NCOs to provide the backbone of his own regiment. With this kind of backing it was relatively easy to effect a transfer. In December 1914 they were commissioned into the Grenadier Guards.

Although they were a little slower off the mark, Crookshank and Macmillan had similar experiences. Crookshank initially obtained a commission with the Hampshire Regiment.11 Then a ‘course of instruction at Chelsea’ gave him ‘furiously to think, and made me decide for a transfer into the Grenadier Guards, in spite of arguments on the part of the 12 Hants and offer of a captaincy’.12 While Lyttelton and Cranborne were at Harwich, Macmillan was at Southend with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. He too saw that his battalion would be used as a training establishment. His later recollection tallies so closely with Lyttelton’s experience that it has the ring of truth. He hung on, but ‘after Christmas [1914] was over and my twenty-first birthday approaching, I began to lose heart’. As Lyttelton and Cranborne had turned to Lord Salisbury to use his influence, so Macmillan ‘naturally’ turned to his mother: ‘I was sent for and interviewed by…Sir Henry Streatfeild [the officer commanding the Grenadiers’ reserve battalion in London],’ Macmillan recalled. ‘It was all done by influence.’13 Sir Henry had become an old hand at dispensing these ‘favours’. It must have seemed that virtually every English family with social influence and a son of military age was beating a path to his door.14

There were, however, few more decisive ways in which to emerge from the protective carapace of family influence than to join a front-line combat unit on the Western Front. The superior connections of Lyttelton and Cranborne gave them the first crack of the whip. They crossed to France together on 21 February 1915 and joined the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, on duty as part of the 4th Guards Brigade in northern France. They were immediately thrown into the classic pattern of battalion life: alternations between the trenches and billets behind the front line. The trenches they found themselves in were also typical of a quiet but active sector. Each side was using snipers and grenade throwers to harass the other and artillery shelled the positions intermittently.15

Beyond the physical dangers of trench warfare the most striking feature of their new world was the regimental ‘characters’. These were the regular officers who had joined the Guards in the late 1890s. Their years of peacetime soldiering had inculcated them with the proper Grenadier ‘attitude’. Promotion in peace had been glacially slow. At the time when the new arrivals encountered them they were still only captains or majors, the war being their chance for advancement. By the end of it those that survived were generals. They were attractive monsters, the ideals to which a new boy must aspire.

The second-in-command of the 2nd Battalion was ‘Ma’ Jeffreys, named for a popular madam of his subaltern days. A huge corvine presence, Jeffreys was known for his utter dedication to doing things the Grenadier way. He was a reactionary who regretted that the parvenu Irish and Welsh Guards were allowed to be members of the Brigade of Guards. It should be Star, Thistle and Grenade only in his view.16 E. R. M. Fryer, another Old Etonian, described by Lyttelton as the ‘imperturbable Fryer’, who joined the 2nd Battalion in May 1915, regretted that ‘Guardsmen aren’t made in a day and I was one of a very small number who joined the Regiment in France direct from another regiment without passing through the very necessary moulding process at Chelsea barracks’. He found himself being given special, and not particularly enjoyable, lessons by Jeffreys on how to be a Grenadier.’17 Jeffreys was considered to be ‘one of the greatest regimental soldiers’.18

Many years after the fact, Lyttelton admired Jeffreys as an example of insouciant courage. A runner was missing and Jeffreys, accompanied by his orderly ‘in full view of the enemy and in broad daylight, strode out to find him, and did find him. By some chance, or probably because the enemy had started to cook their breakfasts, he was not shot at. Such actions are not readily forgotten by officers or men, and the very same second-in-command, who had without any question risked his life…would have of course damned a young officer into heaps for halting his platoon on the wrong foot on the parade ground.’19 While he was serving with him, however, he admired him as a courageous realist: ‘He is exceedingly careful of his own safety,’ he noted in June 1915, ‘where precautions are possible, but where they are not courageous. Any risk where necessary, none where not.’ When his commanding officer was killed at Festubert, he showed no emotion: ‘after seven months in the closest intimacy with a man whom he liked, you might have thought that that man’s death by a bullet which passed through his own coat would have shaken him. Not at all.’20

‘Boy’ Brooke, who was brigade-major of the 4th Guards Brigade and later CO of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, never spoke before luncheon. He treated his subordinates to ‘intimidating silences, when the most that could be expected was a curt order delivered between clenched teeth, derived from a slow acting digestion, which clothed the world in a bilious haze until the first glass of port brought a ray of sunshine’. After luncheon he was ‘charming, helpful and humorous’.21 Boy could take a dislike to a junior officer. One such, who was ‘rather over-refined and a fearful snob’, ‘should not’, he believed, ‘have found his way into the regiment’. Arriving at the end of a five-hour march, Brooke could not find his billeting party. Eventually the officer ‘emerged from an estaminet, and gave some impression of wiping drops of beer from his moustache. He came up and saluted, and not a Grenadier salute at that. His jacket was flecked with white at the back’ from sitting against the wall of the pub, ‘“Ay regret to inform you, Sir, that the accommodation in this village is quite inadequate”.’ To which Brooke replied, ‘“Is that any reason you should be covered with bird-shit?”’ and had him transferred.22

Lord Henry ‘Copper’ (he was red-haired and blue-eyed) Seymour and ‘Crawley’ de Crespigny, a family friend of the Cecils, were 2nd Battalion company commanders in 1915. Lord Henry had had to take leave of absence from the regiment because of his gambling debts. As a result he had been wounded early in the war while leading ‘native levies’ in Africa. He evaded a medical board and found his way to France. His wounds had not healed and needed to be dressed regularly by his subalterns. He was a notorious disciplinarian.

De Crespigny was also a fierce disciplinarian on duty but notoriously lax off duty with those he liked. He had been a well-known gentleman jockey, feared for having horse-whipped a punter who suggested he had thrown a race. Since his best friend was Lord Henry, he was known to treat officers with gambling debts lightly while damning anyone who reported any of them as a bounder. He suffered greatly with his stomach as a result of the alcoholic excess of his early years.23 ‘Hunting, steeplechasing, gambling and fighting were “Crawley’s” chief if not only interests’, remembered Harold Macmillan. Macmillan ‘never saw him read a book, or even refer to one. To all intents and purposes, he was illiterate.’ Even when ordered to desist, because they made him too visible, ‘Crawley’ always wore gold spurs.24

Whatever private thoughts Lyttelton and Cranborne had about their new life, they kept up a joking façade for their families back in England: ‘The worst of it is that the hotel is very bad,’ Lyttelton reported to Cranborne’s mother, ‘if (as Bobbety and I have hoped) we come to explore the fields of battle after the war with our respective families en masse we shall have to look elsewhere for lodging. By Jove how we shall “old soldier” you.’25 A ten-day stay in Béthune, punctuated by light-hearted ‘regimentals’, boxing matches and concert parties, was merely a prelude to more serious business.

On 10 March 1915 the 4th Guards Brigade marched north to take part in an attack around Neuve Chapelle. The attack proved to be a bloody disaster. Luckily for the new officers they did not take part. Twice the battalion prepared to go over the top but twice was ordered to stand down. Within their first three weeks at the front, Cranborne and Lyttelton experienced manning the front line, the off-duty regimental routine and the nightmarish possibilities of the offensive. The horrors of war were all too apparent. The battalion returned to trenches near Givenchy that were neither deep enough nor bulletproof. The experience was nerve-jangling. German artillery and mortar fire was effective against these trenches. On one occasion such fire was induced for frivolous reasons: the Prince of Wales visited the battalion and ‘tried his hand at sniping, and…there was an immediate retaliation’. The threat of mines was constant: ‘everyone was always listening for any sound’. In May the first reports of German gas attacks further north at Ypres arrived and there were desperate attempts to rig up makeshift respirators. The visible landscape was grim. ‘The village was a complete ruin, the farms were burnt, the remains of wagons and farm implements were scattered on each side of the road. This part of the country had been taken and re-taken several times, and many hundreds of British, Indian, French and German troops were buried here.’26

Givenchy was also their first sight of ‘war crimes’ or ‘Hun beastliness’. Anyone wounded in trench raids was hard to recover. The Germans fired at the stretcher bearers who tried to reach them. Cases occurred ‘of men being left out wounded and without food or drink four or five days, conscious all the time that if they moved the Germans would shoot or throw bombs at them. At night the German raiding parties would be sent out to bayonet any of the wounded still living.’ It is unclear whether the ‘beastliness’ was solely on the German side. Certainly by 1916 there were clear instances of the British refusing to take prisoners on the grounds that ‘a live Boche is no use to us or to the world in general’.27 Indeed, a memoir written by a private in the Scots Guards about his experiences later in the war was at the centre of German counter-charges in the 1920s about British ‘war crimes’. The private, Stephen Graham, reported that the ‘opinion cultivated in the army regarding the Germans was that they were a sort of vermin like plague-rats and had to be exterminated’. He provided an anecdote set near Festubert, where both Lyttelton and Cranborne fought: ‘the idea of taking prisoners had become very unpopular. A good soldier was one who would not take a prisoner.’28 Even leaving aside ‘war crimes’, the fighting was desperate and personal. Armar Corry, an Eton contemporary of Lyttleton and Cranborne, led a wire-cutting party that ran into a German patrol. Corry shot one of the Germans, as did his sergeant. His private threw a grenade. The German officer leading the patrol drew his pistol and shot Corry’s sergeant, corporal and private. With his entire party dead, Corry fled for his life.29

Whatever the extent of the brutalization Lyttelton and Cranborne were undergoing, they were certainly becoming cynical about their senior commanders. In March a printed order of the day arrived over the name of Sir Douglas Haig, who was immediately pronounced an ‘infernal bounder’. There was ‘much angry comment’ from the junior officers about Haig’s ‘bombastic nonsense’. Looking out from his trench, Lyttelton commented: ‘the attacks on Givenchy had failed…I know the position from which these attempts were launched and a more criminal piece of generalship you cannot imagine.’30 Five days after the launch of the Festubert offensive in May, Lyttelton wrote: ‘There is some depression among the officers at the great offensive…We are rather asking ourselves: if we can’t advance after that cannonade how are we to get through?’31

Their anger at and fear of the incompetence of the army commander was mitigated, however, by a continued belief in the superiority of the Guards. The Indian troops and the Camerons alongside whom they fought may have ‘showed the utmost gallantry in the attack, but their ways are not ours at other times. When it comes to bayonet work they are as courageous as we are, but they haven’t got the method, the care or the discipline to make good their gains, or show the same steadiness as the Brigade.’32 Lyttelton and Cranborne were also buoyed up by each other’s company. ‘I had a very amusing talk with Bobbety yesterday,’ Oliver wrote in April, ‘we nearly always have a good crack now and great fun it is. The more I see of him the more I like him.’ The two young men found themselves convulsed by laughter at the thought that the pictures on the date boxes they received in their food parcels looked exactly like the paintings of an ‘artistic’ acquaintance of theirs, Lady Wenlock.33

Although the Guards Brigade had seen plenty of action since Lyttelton and Cranborne joined their unit in February, it had been used as a support formation rather than an assault unit. The 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards was finally committed to lead an attack on 17 May 1915, eight days after the beginning of the battle of Festubert. Lyttelton and Cranborne had the chance of a brief conversation before the battle began. They were, Lyttelton wrote, ‘pretty cheerful as it was clear that we were in the course of wiping the eye of the rest of the army and justifying the German name of “the Iron Division”’.34 They began moving up at 3.30 in the morning in extremely difficult conditions. The Germans were shelling all the roads leading towards the trenches so the battalion had to move at snail’s pace in dispersed ‘artillery formation’ over open ground. Confusion reigned. ‘When it reached the supports of the front line, it was by no means easy to ascertain precisely what line the Battalion was expected to occupy. Units had become mixed as the…result of the previous attack, and it was impossible to say for certain what battalion occupied a trench, or to locate the exact front.’

It was not until late afternoon that the battalion started to move towards the actual front line. The route was clogged in mud and it was dark before they reached the front trenches. ‘The men had stumbled over obstacles of every sort, wrecked trenches and shell holes, and had finally wriggled themselves into the front line.’ The German trenches captured on the previous day which they passed over ‘were a mass of dead men, both German and British, with heads, legs and other gruesome objects lying about amid bits of wire obstacles and remains of accoutrements’.35 ‘It was a night,’ Lyttelton recalled a week later, ‘I shall never forget.’ The encounter with such carnage sickened him but ‘only turned me up for about ten minutes. After that,’ he admitted, ‘you cease to feel that you are dealing with what were once men…We were trying to drag a body out – it had no head – and I found by flashing a light that one of my fellows was standing on its legs. So I said, “Get off. How can we get it out if you stand on it, show some sense.” Then I flashed my light behind me and I found I had both feet on a German’s chest who had [been] nearly trodden right in.’36

The advance had been so difficult that the commanding officer, Wilfred Smith, decided that he could not launch his attack on the position known as ‘La Quinque Rue’ as he had been ordered. He decided instead to wait until dawn. Ma Jeffreys was put in charge of the front line, commanding 2 and 3 Companies. Cranborne was commanding a platoon in 2 Company with Percy Clive, a Conservative MP serving as a ‘hostilities only’ officer, as his company commander. Held in reserve were 1 and 4 Companies. Lyttelton was thus further back with his platoon in 4 Company, commanded by ‘Crawley’ de Crespigny.

The 18th of May dawned misty and wet. Visibility was so bad that the attack was postponed once more. They lay in their waterlogged scrapes all day. Suddenly at 3.45 in the afternoon a peremptory order arrived to attack at 4.30 p.m. Jeffreys had to make hurried preparations. He decided to launch the assault using 3 Company, with one platoon of 2 Company under Cranborne in support. Haste proved fatal. The attacking force was decimated. A short artillery bombardment failed to knock out the German machine-guns. As a result ‘the men never had any real chance of reaching the German trenches…the first platoon was mown down before it had covered a hundred yards, the second melted before it reached even as far, and the third shared the same fate’. Armar Corry was the only officer in the company to survive.37

Cranborne, however, cheated death. He did not lead his platoon forward into this maelstrom. Indeed, he was rendered unfit to do anything by the noise of the battle. Accounts differ about what rendered him hors de combat. The regimental history records that he was ‘completely deafened by the shells which burst incessantly round his platoon during the attack’.38 His own medical report, based on a doctor’s examination on 26 May, states: ‘Near Festubert on 18 May 1915, he became deaf from the noise of rifle fire close to his left ear. He also had “ringing” noises in that ear.’39 Near the stunned Cranborne a fierce argument raged between the remaining officers of the battalion. Percy Clive, Cranborne’s company commander, had realized that the attack was a senseless massacre. When Ma Jeffreys ordered him to lead 2 Company forward once more, Clive refused to obey on the grounds that to advance was plainly suicidal. As a result the battalion stayed put. As the casualties, including Cranborne, were evacuated, the brigade major, ‘Fat Boy’ Gort, came up to investigate. Gort, ‘the bravest of the brave’, who finished the war bedecked with medals including the Victoria Cross, agreed with Clive. Lord Cavan, the Grenadier commander of the 4th Guards Brigade, ordered the battalion to dig in where it lay – they had advanced about 300 yards and come up short of their objective by about 200 yards.40

That night Lyttelton moved up with 4 Company to relieve the shattered remnants of 3 Company: ‘it was pitch dark, raining and cold’. He and another officer went out to try and recover some of the wounded. ‘It was a bad job. Some of these fellows had crawled into shell-holes about twenty feet deep and getting them out was a critical business.’ ‘The whole place,’ wrote Lyttelton as he tried to piece together his experiences afterwards, ‘was a sea of mud, and the scene still remains incoherent in my memory, plunging about for overworked stretcher bearers, falling into shell-holes, losing our way, wet and tired, we felt all the time rather impotent.’41 Opinion among the surviving battalion officers was that the whole affair had been mismanaged. The generals had bungled in ordering them to attack on the afternoon of the 18th with so little warning.42

The battle of Festubert convinced the relatives who had been instrumental in getting men into the Guards that service with a combat infantry battalion on the Western Front was not necessarily a good idea. When Cranborne was shipped home, it was discovered that his injuries were not serious and that he would soon be able to rejoin his regiment. ‘The ear,’ his medical board was told, ‘has been examined by a specialist and has been diagnosed as a course of labyrinthine deafness; prognosis good.’43 He was granted three weeks’ leave. While he was on leave the Cecils’ family doctor diagnosed him with appendicitis. His friends regarded this as an amazing stroke of luck,44 as was clear from the letters of commiseration he received. It must be sore having a bad ear and a bad gut: ‘But,’ one friend serving with a line infantry regiment in France, added, ‘I wonder if you are sorry. For goodness’ sake don’t come out here again.’45 Lyttelton cheerfully chipped in, ‘There is a great deal of satisfaction in hearing from someone whom you have just seen in Flanders, at Park Lane.’46 Another friend, also recuperating from wounds, wrote, ‘I think we are both well out of it for a bit, Bobbety, don’t you agree with me. It was the most unpleasant two months I’ve ever spent and I don’t think you cared for it much – did you?’47

Cranborne attended regular medical boards. On each occasion his leave was extended. There seemed to be enough time to attend to his own affairs. He proposed marriage to Betty Cavendish, the daughter of Lord Richard Cavendish, the younger brother of the Duke of Devonshire. It was an entirely suitable match between two of the great aristocratic families of England, though Bobbety’s father wryly noted that his son’s choice had let him in for some difficult dowry negotiations: Dick Cavendish was notorious for pleading poverty.48 Lord Richard, however, did his new son-in-law a good turn by intervening with the War Office to have his leave of absence extended to the end of the year.49

Families were caught between a desire to see their sons removed from danger and their sons’ desire not to be seen pulling strings to escape the front line. Another junior officer in the Grenadier Guards, Raymond Asquith, son of the prime minister, angrily told his wife that: ‘The PM in disregard of a perfectly explicit order from me to take no steps in that direction without my express permission has tipped the wink to Haig…no one will believe that this [staff] job has been arranged without my knowledge…So in mere self-defence I shall have to try to get back to the Regiment when the fighting season starts.’50 He was right to suspect that people were keeping a spiteful eye on these things. When Asquith himself was killed, one of his father’s Cabinet colleagues wrote to a newspaper editor, ‘As for Lloyd George himself, he risks very little. His sons are well sheltered.’51

Someone was looking out for Oliver Lyttelton. Soon after meeting his mother in Brussels, he was offered a post as ADC to Lord Cavan. Cavan needed an ADC because he was to give up the 4th Guards Brigade and take command of a line division. ‘I feel very weepy reading of your meeting with Oliver and the news of Cavan’s offer,’ wrote Lyttelton’s uncle to his mother. ‘I do hope to heavens there will not be a hitch in Oliver’s appointment and that nobody will put any obstacles in the way or, which is just as important, [he] feel[s] that he oughtn’t to take it.’ If strings had been pulled, that was no cause for shame. ‘After all the boy has had his grilling in the trenches, gone out…and done the brave thing and if some general does choose to pick him out one can only be thankful…Of course there are plenty of risks still but it must be much safer than a platoon leader.’52 His friends agreed that his removal from the front line was a matter for celebration.53

In fact intervention by figures considerably more eminent even than the Lyttelton clan was to change the pattern of the war for both Lyttelton and Macmillan. As Lyttelton took up his post, Lord Cavan was preparing himself to meet King George at Windsor. Cavan had gone home to visit his wife, who was sick with diphtheria. Calling in at Chelsea barracks, he was shocked when Streatfeild told him that not only would a fourth battalion of Grenadiers be formed, but that it would be sent to France as part of a Guards division. Two days later His Majesty graciously informed Cavan that he would command the new formation. As far as Cavan could tell, the idea had been put to the king by Lord Kitchener. It seemed that his lordship was keen to curry favour by giving the Prince of Wales, who was attached to the Grenadiers, a bigger stage on which to perform. Cavan did not believe that the division had any military logic. He was horrified to discover that the four battalions of Grenadiers were to be formed into a single Grenadier brigade within the division. This, no doubt, seemed a glorious idea in Windsor and Whitehall, but it struck the Grenadier Cavan as disastrous. As he explained to Kitchener, ‘if they went into action we might lose at one blow more officers than we could replace all belonging to one Regiment’. Although Cavan could do little about the fait accompli of a Guards division, he at least averted the potential destruction of the Grenadier Guards by insisting that all brigades contain a mixture of battalions from each Guards regiment.54

Because of the creation of the Guards Division Lyttelton did not leave the Guards for a line division: he became a junior staff officer in the Guards Division. As Lyttelton left the 2nd Battalion, Crookshank joined it, having missed Festubert cooling his heels in a base camp near Le Havre. They were eventually able to meet up for tea and bridge when Lyttelton came back to visit his old unit.55 Macmillan was also affected by the reorganization. Gazetted into the Grenadiers in March, he was assigned to the new 4th Battalion in July 1915. It was almost as if the old Eton pattern remained in place. The two Oppidans had used their influence to be first in and first out. Now the scholars had arrived. If Festubert was the baptism of fire for Cranborne and Lyttelton, Loos was to be Crookshank and Macmillan’s battle.

The first to arrive, Crookshank, had a hot welcome. Three days after he reached the 2nd Battalion they were sent into a set of notorious trenches known as the ‘Valley of Death’. Ten days later they moved to better trenches only to face the threat of a new, and lethally effective, German trench mortar – the Minenwerfer. Even when they retired to billets in Béthune, their luck did not improve. The Germans shelled the town, rendering their rest period ‘a farce’.56 It was in the trenches near Givenchy, however, that Crookshank made his name in the regiment. The battle of Festubert had proved to the satisfaction of both British and Germans that charging enemy machine-gun emplacements was suicidal. The obvious alternative was to approach the enemy underground. Both sides had initiated a large number of tunnelling operations to set mines. The Germans in the Givenchy sector were particularly keen on these operations and had seized the upper hand: they made the Guards’ life both dangerous and miserable through a combination of mines and mortar bombs lobbed into the craters they created. ‘The casualties from mining and bombing in addition to those from rifle fire and shells were very heavy,’ noted the regimental history.

Digging deeper trenches and counter-mines became an unpleasant necessity for the Guards. Percy Clive and Crookshank were leading a digging party into an orchard near the trenches when they were caught in a German mine explosion. By the greatest good fortune they were just short of the mine when it went off. The whole ground moved up in one great convulsion, and when it settled down several men were completely buried. Clive was shot straight up in the air by the blast and came down so doubled up that he nearly knocked his teeth out with his knees. Crookshank, on the other hand, was buried by the earth thrown up in the explosion. It was a perilous situation. He was trapped in an earthen tomb, quite unable to move. No one on the surface could see where he was. If no one came to his rescue he would suffocate. If Clive had rescued Cranborne’s platoon from certain death by disobeying Jeffreys’s order to advance, his quick thinking saved Crookshank also. Although cut, bruised and groggy himself, he had enough presence of mind to work out where Crookshank had been standing just before the mine went off. Clive directed his men to dig hard.57 A brother officer estimated that Crookshank had been buried for twenty minutes before the rescue party dug him out. He was in a state of shock but otherwise unhurt. He ‘won his name’ by his insouciant reaction to his experience. By evening he had returned to duty with the company. ‘He didn’t seem to worry at all at his misfortune,’ in the recollection of an officer in 3 Company, ‘and carried on duty as soon as he had been disinterred, minus, however, his cap, and the one he borrowed from a private soldier didn’t fit, and this was his only trouble!’58 Crookshank’s own account of the incident was suitably laconic: ‘I was…buried for a long time, but rescued in the end.’59

Of any of the quartet Macmillan adapted least well to army life. In his memoirs he famously drew the distinctions between ‘gownsmen’ and ‘swordsmen’, characterizing himself as one of the former who had by force of circumstances become one of the latter.60 Lyttelton and Crookshank threw themselves into the role of regimental officer with enthusiasm, whereas Macmillan tried to re-create an intimate bookish coterie in the trenches. ‘My library is indeed very wide and Liberal,’ he noted with satisfaction, already thinking of posterity. ‘I shall try to send back some which I have read and should like to preserve. I have written inside “France Sept. 1915.”’ ‘I have a friend who was said to have read the Iliad “to make him fierce”,’ he told his mother. ‘I confess that I prefer to do so to keep myself civilized. For the more I live in these warlike surroundings, the more thankful I am for all the traditions of the classic culture compared to which these which journalists would have us call “the realities of life” are little but extravagant visions of a fleeting nightmare, lacking true value or permanency.’61 Macmillan and his friend Bimbo Tennant were delighted, for instance, when they rode over for dinner with a friend at the 1st Battalion to find most of the officers, ‘snorting Generals and Majors’, absent. ‘We had,’ Tennant told his mother, ‘a delightful evening à trois and had one good laugh after another, being all blessed with the same sense of humour, and unhampered by any shadow of militarism.’62 Lyttelton’s letters too were full of pleas for books, but he wanted ‘shockers’ rather than Homer or Theocritus. He even enjoyed Greenmantle by his mother’s friend John Buchan, despite the fact that ‘he hasn’t been within a hundred yards of the truth yet’.63

It was with heartfelt relief that the Guards left Givenchy and marched south. Now that the Guards Division had assembled, Lyttelton, Crookshank and Macmillan were all present. Lyttelton was mounted at Cavan’s side, Crookshank was marching with the 2nd Battalion, Macmillan with the newly arrived 4th Battalion. They all met up at the end of August. To mark the combination of all four Grenadier battalions in one Guards formation, the regiment held a formal dinner to celebrate the occasion. It was, as Macmillan reported, ‘a most unique dinner party. All the officers of the Regiment who are in France – (that) is in the four battalions or on the Staff…There were 96 of us in all.’64 Even the newest and most temporary Grenadier officer was made to feel part of an exclusive club as well as a great and glorious enterprise. ‘I saw many old friends,’ wrote Harold’s fellow 4th Battalion new boy, Bimbo Tennant, ‘and was very happy.’65 Just as important as the élan of the Guards Division was a sense of a more scientific approach to the new warfare. The battalions carried out practice attacks on mock-ups of trenches under the watchful eyes of Jeffreys and Seymour. The army had realized that rifle and bayonet were not necessarily the most effective tools for trench warfare. Weapons that could give infantry more ‘bang for their shilling’, such as grenades, machine-guns and mortars, were coming into vogue. Macmillan was nominated as a bombing officer and spent his time training troops in his battalion in grenade techniques.66

The esprit de corps of the young officers did little to avert disaster at their next engagement, the battle of Loos. It is doubtful whether the Guards Division’s attack at Loos ever had a chance: ‘it had to start from old German trenches, the range of which the German artillery knew to an inch, while the effect of our own original bombardment had died away’.67 Crookshank and the 2nd Battalion arrived on the battlefield on 26 September 1915. During the 27th they slowly worked their way into the old German trenches, Crookshank in the rearguard. Despite their proximity to the battle, however, the order never came to attack.68 The 4th Battalion, however, bore the brunt of it. It was Macmillan who was to experience the full force of the battle.

Owing to incompetent staff work, the 4th Battalion had spent the 26th uncomfortably sitting on a muddy road while a cavalry corps passed by.69 Next day the battalion officers were gathered together by their commanding officer, Claud Hamilton, and told they were to attack Hill 70 just to the east of Loos. Macmillan’s company commander, Aubrey Fletcher, was sent forward to discover the best route into Loos.70 Macmillan himself did ‘not feel frightened yet, only rather bewildered’.71 At 2.30 p.m. on the 27th the battalion advanced down the road into Loos in dispersed formation. They were immediately and heavily shelled by German artillery. To make matters worse, they were enfiladed from the right by a German machine-gun. As they approached Loos, Aubrey Fletcher led them running down a slope into an old German communications trench. Unfortunately he had taken them the wrong way. The brigade commander came galloping down the road and ordered the battalion not to enter the trench but follow him in an entirely different direction. The result was chaos, with the battalion split in half. In the confusion, neither half of the battalion could find the other. The main body of the Grenadiers attacked Hill 70 with the Welsh Guards. Macmillan was lucky to miss this assault. The Guards swept forward taking heavy casualties, but reached the crest of Hill 70. In the heat of battle, however, the Grenadiers advanced too far over the crest and exposed themselves to fire from the next German line. All who took part in this attack were killed.72

Meanwhile the remainder of the battalion, including Macmillan, under the leadership of Captain Jummie Morrison, had no orders whatsoever. They decided to attach themselves to the 2nd Guards Brigade and attack Puits 14, a German strongpoint to the north. This attack too was a disaster. Unbeknown to the Grenadiers, the 2nd Guards Brigade had withdrawn without them: they thus ‘found themselves completely isolated’.73 They had to try and escape by crawling away from the German line. Jummie Morrison was too fat to be a good crawler. As he and Macmillan tried to take their turn, Macmillan was shot in the head. He was incredibly lucky – it was a glancing blow. He was, however, concussed and no longer capable of taking an active part in proceedings.74 As the small, lost and bewildered force tried to make themselves safer by digging in, Macmillan was shot again, this time in the right hand. The bullet fractured his third metacarpus bone. With his right arm crippled and in excruciating pain, he was ordered by Morrison to go back and find a clearing station. The hand wound proved to be much more serious than the head wound: Macmillan was troubled by his right arm for the rest of his life. Within a few days he found himself in hospital at Rouen, ‘more frightened than hurt’.

The Guards Division’s attack on Loos was hardly a triumph of the military art, the 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards alone having lost eleven officers and 342 men – ‘it has been’, Macmillan recorded, ‘rather awful – most of our officers are hit’. Nevertheless the Guards exculpated themselves from all blame. ‘The Guards Division,’ Macmillan proudly proclaimed, ‘has won undying glory, and I was long enough there to see the lost Hill 70 recaptured.’75 Indeed Jummie Morrison’s sad remnant had been sent to dig in on the hill that night, although in truth the Guards had only captured the western slopes, leaving the Germans in possession of the redoubt. From both Macmillan’s perspective as a platoon officer and from Lyttelton’s rather more elevated position at divisional HQ, it seemed that the Guards elite had been let down by Kitchener’s army. ‘Some of the New Army Divisions are rather shaky,’ Macmillan wrote the day before the Guards went into action, ‘my chief feeling at present is one of thankfulness that I am in the Brigade of Guards. All the way up on the road we were greeted with delight by the wounded and all other troops. And it is so much easier to command men who seem to obey orders with engrained [sic] and well disciplined alacrity as soon as they are given.’

‘That the 21st and the 24th divisions,’ Lyttelton confirmed, ‘completely spoilt the show is I fear true.’ Like Macmillan he felt that, as a Guards officer, he was in a position to patronize the line infantry. ‘I’m afraid,’ he observed with all the assurance of a man of twenty-two, ‘that the New Army is trained too much with the idea: Oh we don’t need discipline. These are not recruits driven into the ranks by hunger, they are patriots, it’s ridiculous to ask a well-educated man of forty to salute an officer of twenty, and so on. The alpha and omega of soldiering and training is discipline and drill.’ ‘However,’ he charitably conceded, ‘those divisions of the New Army who have been blooded did quite creditably, the ninth and the fifteenth. The Territorials, who have some tradition if no discipline, attacked with great gallantry if not very efficiently.’ Alternative accounts circulating in London drew his derision: ‘As to the Guards Division being three hours late it is simply pour rire and goes to prove how very little people know of the war.’76

It was not only the Guards that used the ‘Kitchener’ divisions as scapegoats for the failure of the Loos offensive. Haig also laid the blame at the door of their tactical inadequacies. GHQ’s post-mortem on Loos called for an increase in offensive raids and enhanced training for and use of grenades.77 Thus the Guards found themselves thrust back into low-level but high-intensity warfare in the trenches just north of Loos. The post-Loos battle lines meant that in some places the British and German trenches were only thirty yards apart. There were continuous bombing and sniping duels. For the first time 2nd Battalion snipers were issued with telescopic sights, making the duels even more deadly. Crookshank was an early victim.78 On 23 October his company commander took advantage of visionobscuring mist to send him out at the head of a wiring party. He led his men out and back safely. As they gathered more wire to go out again, a German sniper shot him in the left leg. The bullet seems to have been a ricochet, for although it ended the 1915 campaigning season for him, it did no permanent damage. The next day he was safely ensconced on a hospital train heading back to the coast, ‘very comfortable and everything to eat and drink that we wanted’.79 Comfort levels improved even further when he reached England: he was sent to the officers’ nursing home housed in Arlington Street, next door to Cranborne’s London home.

Crookshank’s wound meant that he missed the arrival of a national celebrity to serve with the 2nd Battalion. Winston Churchill, ejected from the Cabinet in disgrace after the failure of the Dardanelles expedition, was assigned to a reluctant Jeffreys to ‘learn the ropes’ before taking command of his own unit. Lyttelton, visiting the battalion dugout of his old unit, was surprised when the ‘well-known domed head and stocky figure’ emerged out of the darkness. It was their first proper meeting: Churchill, following his defection from the Tory party to the Liberals in 1904, had been persona non grata in the Lyttelton circle during Oliver’s school and university days. That night at dinner Churchill held the floor. ‘We listened – we had to,’ Lyttelton remembered, as Churchill expounded his idea that the ‘land battleship’ or ‘tank’ would break the deadlock on the Western Front.80 Churchill went on to describe to his sceptical audience the first trials of the new weapon that had taken place at Hatfield House. Later he was to present Lord Salisbury with the first tank as a memento to stand in the grounds.

In his letters home Churchill gave a vivid picture of the brutal war fought by the Grenadiers in the winter of 1915. ‘Ten grenadiers under a kid went across by night to the German Trench which they found largely deserted or waterlogged,’ he informed his wife, instructing her for obvious reasons to keep this account to herself.

They fell upon a picket of Germans, beat the brains out of two of them with clubs & dragged a third home triumphantly as a prisoner. The young officer by accident let off his pistol & shot one of his own Grenadiers dead: but the others kept this secret and pretended it was done by the enemy – do likewise. The scene in the little dugout when the prisoner was brought in surrounded by these terrific warriors, in jerkins and steel helmets with their bloody clubs in hand – looking pictures of ruthless war – was one to stay in the memory. C’est tres bon.81

So many regular Guards officers were killed at Loos that ‘even old-fashioned Guardsmen became convinced’ that the ‘patriots’ would have to be used to fill junior command positions: ‘from this time onwards’, noted the official history, ‘the battalions of the Guards Division were officered to a large extent by officers of the Special Reserve with very short training behind them’.82 Lyttelton was one of the first ‘beneficiaries’ of this policy.83 He had never really become comfortable as Cavan’s ADC. Cavan’s other ADC was his brother-in-law, Cuthbert Headlam, who was a good deal older than Lyttelton. Lyttelton was thus very much the youngest and most junior member of the divisional team.84 There was ‘nothing very much to do but fuss about horses and motor cars’. He was thus sanguine when it became clear that his position on the staff was untenable. When the adjutant of the 3rd Battalion went sick with varicose veins in the middle of the battle for Loos, Lyttelton was offered the chance to take his place. ‘It was,’ he admitted, ‘rather unpleasant leaving our comfortable chateau especially as I knew that we were for the trenches and probably for a push…it was certainly not cheering.’85 The offer was, however, too good an opportunity to miss, since he ‘should anyway [have] had to return to duty with the Grenadiers as their losses have been so severe as to amount almost to irreparable’. He consoled his mother with the thought that ‘an Adjutant is far safer than a company officer’.86

To become adjutant of a Guards battalion was quite a promotion. The adjutant was the senior captain in the battalion and in charge of its day-to-day organization. He acted as the staff officer to the commanding officer and was third-in-command in battle. The opportunities for promotion opened up both by casualties and the winnowing out of less forceful officers piqued the ambition of the army’s ‘thrusters’. Although this was really a game for regulars who could aspire to higher command positions, Lyttelton caught the bug. From late 1915 onwards his letters are as much about his ambitions and disappointments concerning further promotion as they are about the routine of trench warfare. He was turning into a first-class ‘thruster’.

The importance of being a ‘thruster’ was brought home to Lyttelton when he arrived at the 3rd Battalion. This was a world away from Jeffreys’s élite 2nd Battalion in which Lyttelton had been schooled. ‘I never realized till that day,’ he wrote after a month with his new unit, ‘how good the 2nd Battalion were.’87 Like the 4th Battalion, the 3rd had been badly mauled at Loos. Only six officers had survived the battle and Lyttelton did not find them an impressive group: ‘I knew some of them but was not writing home about them.’ ‘They were all in a state of “Isn’t it awful” and doing very little to make it less so.’88 As one of those officers later confirmed, ‘I think we felt a bit dazed and were glad enough when we were relieved [in the front line].’ The situation was no better among the other ranks. The battalion had been severely weakened in the summer of 1915 when it had been ‘skinned’ of some of its best NCOs to create the 4th Battalion. After Loos most of the remaining experienced NCOs and nearly 400 men were dead and had been replaced by new drafts.89

The worst problem by far, it so happened, was the commanding officer. Lieutenant-Colonel Noel ‘Porkie’ Corry was the senior battalion commander in the brigade. He had specifically requested Lyttelton’s assignment to his battalion. Corry’s son, Armar, had not only been at Eton with Lyttelton but had also served with him in the 2nd Battalion, where he gained the reputation of an audacious trench raider, finally falling victim to a severe face wound during the pre-Loos skirmishing of August 1915. He was to lose his life at the Somme in 1916. Corry père was another matter entirely. Behind the lines he cut quite a dash.90 The trenches, however, had broken his nerve. He was an incompetent, a coward and a drunkard.91 Even worse for Lyttelton, he was desperately trying to deny his inadequacies both to himself and to his superiors by blaming others for the shortcomings of his unit. The situation was excruciatingly dangerous. Like the 2nd Battalion, the 3rd was expected to undertake aggressive skirmishing. Such operations were potentially deadly enough when carried out by brilliant young ‘thrusters’ under the command of equally brilliant officers like Jeffreys; they were doubly so when run by incompetents. Just before Lyttelton arrived, the battalion had been surprised by a German attack as they ham-fistedly tried to change over forward companies. ‘The Germans had got possession of the whole battalion’s front’ and had to be ejected by the Coldstream Guards.92

As the 3rd Battalion moved back into the trenches near Loos Lyttelton’s heart sank. The manoeuvre was carried out in a farcical manner. Porkie was ‘rather like a monkey on hot bricks and one could see he was no good’. He didn’t seem to know what his battalion was doing and blamed everybody else for the confusion. He fastened on to the problem of sandbags. ‘It was so simple,’ noted a frustrated Lyttelton, ‘send a party for sandbags with an officer and let them follow us up the trench. Meanwhile let us go on. But he would have it that the whole battalion should go off and get the sandbags…come back and go on.’ Lyttelton was forced to stand in a trench arguing with his commanding officer. His arguments prevailed but they wasted precious time, moving neither forwards nor backwards, until the Germans started to shell their communications trench. As Lyttelton noted viciously: ‘this bit of shelling put the wind up Porkie’ and all talk of sandbags was abandoned in the rush to a safer position.93

Things became even worse when the battalion was given the chance to ‘recover its name’ by carrying out a bombing attack on ‘Little Willie’, on one of the flanks of the formidable German strongpoint known as the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Before the attack could go in, the battalion was ordered to dig a trench over to the Coldstreams to ensure that grenades could be moved up quickly and safely enough to keep the attack going. Lyttelton soon realized that Corry was in no hurry to push on with work on the trench since once it was completed the battalion would have to go ‘over the top’ on its raid. Lyttelton decided that ‘if anything was to be done I should have to command the Battalion’. Although he was ‘enjoying myself beyond measure’ at the taste of command, he could not persuade his fellow officers to speed up the sapping by taking the risk of climbing out of the trench and digging over ground at night. ‘This was awful,’ he realized, ‘because Porkie has got a poorish reputation for ability and is supposed to be likely to cart you.’ He had taken responsibility and now risked being made a scapegoat for failure. Since the trench was not finished in time the Coldstreams had to step in once more and carry out the operation for the Grenadiers. Lyttelton ‘could have cried with chagrin and disappointment’. He had never been ‘so bitterly despondent as I was that morning’. It was more ‘loss of name to the battalion’.94 The post-mortem was equally depressing. The captain who had been digging the trench had in fact ‘carted’ Corry to John Ponsonby, the commander of the 2nd Guards Brigade, before Corry could blame anyone else. Corry ‘looked grey and hopelessly rattled and walked up and down swearing, accusing, excusing, asking me questions no-one could answer like a child. “Do you think the Brigadier thinks”…“It’s all the fault of the Coldstreams, they didn’t help”.’ Then the word came down the line that the brigadier was not particularly worried by the trench-digging fiasco, ‘which restored Porkie’s morale at once’.95 At the next opportunity he got ‘very tight, and began to talk the most awful rot’.96

The wake-up call of the failed bombing operation did nothing to make Corry change his ways. He always seemed to find routes to avoid action. All he did was waste time by looking through a periscope, claiming ‘he can see Germans everywhere’. His boasting was incessant: ‘if he goes up alone, which is rare’, Lyttelton complained, ‘he always comes back having had the narrowest shave and having behaved with the utmost coolness’. The drinking continued to get worse, often leaving him incapable by the afternoon. He claimed credit for work done by his subordinate officers. To add insult to injury, Lyttelton noticed with the eye of an experienced gambler, he even cheated at poker.97

The commanding officer and adjutant of an infantry battalion perforce had an intimate relationship. Pressed daily into close contact with Corry, Lyttelton came to loathe him. While enjoying the increased responsibility thrust on his shoulders, he was placed in a dilemma. ‘I wish to heaven he would be sent home but all the time I have to work to keep him on the job and not let him flout.’ He began to despair that his superiors had not noticed Corry’s incompetence clearly enough to relieve him of his command. By December he had made up his mind that he would ‘cart’ Corry as soon as he made a mistake that was clear and important enough to be laid at his door.98 He rightly suspected that Corry was not the only one being blamed for the battalion’s plight. Many of the other junior officers in the battalion thought he himself was ‘too casual and conceited’.99 He was, they charged, a ‘bully and a toady’.100 What he thought of as a difficult balancing act they saw as sucking up. A badly run unit was corrosive of relationships on all levels.

Fortunately for Lyttelton’s reputation, the standards of the Brigade of Guards had not in fact slipped as much as he was coming to believe. Even without his dropping his commanding officer in the soup, senior officers had noticed that Corry was not up to the job. He was an old comrade of many of them, but he had to go. At the turn of the year, as Lyttelton was settling in to bear the same yoke he had carried through the autumn and winter of 1915, suddenly Corry was gone and Lyttelton found himself in temporary command of the battalion. Within days Ma Jeffreys arrived in a black temper. He had been confidently expecting promotion and command of a Guards brigade.101 ‘I hate,’ he confided to his diary, ‘going to yet another temporary job, but I am told that it is in the best interests of the Regiment and I am expected to “pull the battalion through”.’102 A brisk tour of inspection suggested that the situation was not as black as had been thought. Corry really had been the main problem. After parading each company and talking to every officer, Jeffreys came to the conclusion that ‘there is nothing much wrong except inexperience and that they are a bit “down on their luck”’. He was particularly complimentary about Lyttelton. His former subaltern had, he noted, ‘the qualities to make a good’ adjutant. In particular he had ensured that ‘the system of the Regiment is being carried out and all want to do their best’.103 The warmth was reciprocated. ‘Ma was wonderful,’ wrote a relieved and delighted Lyttelton. ‘As soon as he found there was nothing very wrong he cheered up enormously.’104 In fact Jeffreys found that after his initial pep-up the battalion did not need the special attention of a senior officer and he turned the unit over to Boy Brooke. After some difficult months, Lyttelton now found himself once more in an élite formation.

Lyttelton was becoming a valuable asset to the army. All too few of those volunteer officers who had gained experience in 1915 were still at their posts at the beginning of 1916. As the 1916 campaigning season approached, the army therefore started to comb through its sick lists to identify officers fit enough to be sent back to France. Cranborne, Crookshank and Macmillan were each examined by medical boards, though with somewhat different results. While Macmillan, with his hand wound, and Crookshank, with his leg wound, were declared fit for service on the Western Front, Cranborne was passed as fit only for light duties.105 His services as an ADC had already been requested by the commander of the reserve centre in Southern Command.106 Although he was refused this dignity by a tetchy personnel officer in the War Office, he was allowed to join the general as an unpaid orderly.107 Thus Cranborne departed for Swanage while Macmillan and Crookshank headed back to the 2nd Battalion in the Ypres salient.

Crookshank was delayed at Le Havre. Like Macmillan the year before, he was caught up in the growing technological sophistication of the British Army. Whereas Macmillan was a bombing officer, Crookshank now became a Lewis gun officer. The Lewis gun was a relatively portable machine-gun designed by an American for the Belgians and brought from there to Birmingham in 1914. By the start of 1916 large numbers were being issued to infantry companies.108 The Lewis gun went some way to compensating for the decline in musketry standards which affected the whole army as long-service professionals were replaced by volunteers and finally by conscripts.109 Crookshank was even so less than delighted with his new role. After his Lewis gun course he ‘knew as little at the end as at the beginning’.110 He found it hard to drop into the role of the ‘old soldier’. He was ‘getting rather bored with some of our more stupid brother officers’.111 Giving a series of lectures on the trench attack to new arrivals, he felt a complete fraud, ‘knowing nothing about it’.112 He even managed to miss duties with badly blistered feet caused by wearing natty but insubstantial pure silk socks.113

Macmillan would have been glad to stay on the coast with Crookshank. He looked forward to their new posting with dread.114 Indeed, Macmillan’s rebaptism of fire was brutal. Under the command of Crawley de Crespigny, Macmillan’s new battalion was still taking a robust view of its aggressive role in the trenches. On Good Friday 1916 he found himself in charge of a platoon, in an exposed trench near Ypres, completely cut off from other British forces. He could reach neither the unit on his left nor right. The communications trench to his rear was too dangerous to use in daylight, so he could not even contact the rest of his company. His only solace was reading the Passion in Luke’s Gospel. He was cold, lonely and frightened and ‘already calculating the days till my first leave’.115

By early 1916 Lyttelton had sloughed off any hint of boyishness. He was an experienced soldier who had had responsibility beyond his years thrust upon him. His letters home were detailed, hard-edged and often cynically funny. Macmillan, on the other hand, retained a certain pompous innocence: he didn’t ‘know why I write such solemn stuff’ but write it he did. The army possessed that ‘indomitable and patient determination, which has saved England over and over again’. It was ‘prepared to fight for another 50 years if necessary until the final object is attained’. The war was not just a war, it was ‘a Crusade’: ‘I never see a man killed but think of him as a martyr.’116 He found the words of the French high command at Verdun – resist to the last man, no retreat, sacrifice is the key to victory – so stirring that he copied them into his field pocketbook. Whereas Lyttelton had felt the prick of ambition, Macmillan had to deflect his mother’s demands that he should get on. His ambition was to survive and ‘get command of a company some day’, though he disparaged his mother’s wish that he should get out of the front line to ‘join the much abused staff’.117

Macmillan and Crookshank were finally united in mid June near Ypres. Crookshank had slowly made his way to the battalion in an ‘odd kind of procession’, braving the danger of inadequate messing facilities, ‘perfectly abominable…a disgrace to the Brigade’.118 Each was delighted to see the other. If they had to be in this awful place, it was at least some solace to tackle the task ahead with your closest friend. They immediately became tent-mates.119 Crookshank was assigned to his old platoon: ‘rather like going to school after the holidays seeing so many of the old faces after the long absence’.120 Crookshank believed he had done rather well in the battalion the previous year and was much less self-deprecating than Macmillan about his chances of promotion. He was thus ‘very annoyed and disappointed’ when both of them were transferred into 3 Company under the command of another subaltern, Nils Beaumont-Nesbitt.121 In early July they went into the ‘Irish Farm’, ‘one of the worst positions [the battalion] had been in’. It offered 1,300 yards of ‘trenches’ that were ‘mainly shell holes full of water with no connecting saps, constant casualties and back-breaking work.’122 Raymond Asquith described it as ‘the most accursed, unholy and abominable place I have ever seen, the ugliest, filthiest most fetid and most desolate – craters swimming in blood, dirt, rotting and swelling bodies and rats like shadows…limbs…resting in the hedges’. The aspect that disturbed him most was ‘the supernaturally shocking scent of death and corruption [so] that the place simply stank of sin and all Floris could not have made it sweet’.123

Crookshank escaped the worst by being sent on a Lewis gun course at Étaples, ‘mechanism cleaning and stripping (I did but very slowly)’, although he encountered another mess that was the ‘absolute limit – had some words with the CO on the subject of servants, went to dine at the Continental’.124 Crookshank was a fusspot. He liked things just so. His doting mother made sure that he was never short of funds to make himself comfortable. As a result his girth was beginning to swell. He was lucky to have in such close attendance Macmillan, who always appreciated the waspish humour with which he leavened his perpetual moaning. Although Crookshank’s undoubted bravery won him friends, he could be an irritating companion in those trying circumstances.

Macmillan himself, on the other hand, having had little opportunity to shine during his last spell at the front, ‘made his name’ from the battalion’s unpromising position. On 19 July he led two men on a scouting patrol in no man’s land. They managed to get quite near the German line, but then ran into some German soldiers digging a sap. A German threw a grenade, the explosion from which wounded Macmillan in the face. One of his men was also wounded and they struggled back to the British lines.125 Macmillan’s wound was serious enough for him to have left the battalion, but he refused to do so out of a mixture of bravado and opportunism piqued by Crookshank’s more militant attitude to promotion. ‘My first duty is to the Regiment which I have the honour to serve,’ he decided, ‘and not only are we very short of officers of any experience just now…but I was told confidentially by the Adjutant the other day that the commanding officer would probably give me command of the next company vacant, when I had had a little more experience of trench work.’ Macmillan was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery, but more immediately he basked in the good opinion of de Crespigny, who ‘was pleased with me for staying’.126

They all nevertheless knew that these skirmishes in Flanders were a mere sideshow, overshadowed by ‘der Tag – the first day of the great Fourth Army and French push’ on the Somme, leagues away to the south.127 As far as they could tell, ‘the Somme seems to be progressing favourably, if slowly and methodically’. They were all too aware that ‘the casualties have been very heavy’.128 In fact the first and indeed subsequent days of the Somme offensive were a bloody disaster. As the Guards Division was sent marching south, GHQ acknowledged that the loss of men was unsustainable. The Fourth Army would revert to a ‘wearing out’ battle until the ‘last reserves’, of which the Guards were part, could be thrown into a renewed ‘decisive’ attack in mid September.129 News of these disasters soon filtered down to the junior officers and undermined their initial optimism.130 One subaltern in their company was court-martialled for sending an ‘indiscreet’ letter, opened by the censors, criticizing the staff. It was rumoured that this letter was the reason why King George had not inspected the battalion when he visited the Guards at the beginning of August. It was noted that the Prince of Wales, so obvious a presence the previous year, was no longer anywhere to be seen near the battalion.131

On the road Crookshank and Macmillan ‘were having very amusing conversations’. The northern part of the Somme battlefield was even ‘quite a nice change after Ypres’. There was a ‘wonderful view all round especially of the Thiepval plateau’, which they observed for hours. The trenches were very good. Crookshank and Macmillan were even allocated their own dugout, although it proved to be less than a blessing, located at ‘the end of a communications trench junction and well shelled’. They abandoned it after only one night.132 Indeed, it was at night that they had time to mull over the grimness of their situation. Sitting in their shared tent, they were ‘frightfully depressed’ by the fact that their ‘most intimate circle [had been] killed in the push, it’s enough to make anybody feel very sad’. Crookshank was particularly upset by the death of his ‘great friend’ at Magdalen, Pat Harding. Harding, a ‘great Oxford friend’ of Macmillan as well, had already risen to rank of major in a Scottish regiment before he was killed. Not only was the war cruel, it was insidious. Arthur Mackworth, for instance, a young classics tutor who had taught Crookshank at Magdalen, and who escaped the front after being transferred from the Rifle Brigade to the War Office Intelligence Department because of a heart condition, was so tormented by insomnia that he shot himself dead.

They had little time to dwell on these tragedies: they were soon in the midst of a major training programme that continued throughout August and into September to prepare the Fourth Army for its second great push on the Somme. Something of the kind had been tried before Loos, but this was on a much bigger scale. The Fourth Army tried to learn the lessons of the first phase of the offensive and inculcate its troops with the best ways of carrying out trench attacks and of using their equipment.133 One change of doctrine in the summer of 1916 affected Macmillan. Initial operations on the Somme led to a reversal of Haig’s post-Loos enthusiasm for the grenade and a return to the doctrine that ‘the rifle and the bayonet is the main infantry weapon’. Supposedly, ‘when attacking troops are reduced to bombing down a trench, the attack is as good as over’.134 The Guards nevertheless still put considerable emphasis on grenade training, and as their attack at Ginchy was to show, front-line troops would remain deeply attached to their grenades whatever the official prognostications. Macmillan, however, was not called on to resume the role of bombing officer, which he had managed to abandon just before the beginning of the march south. Crookshank’s Lewis guns remained in vogue. Ma Jeffreys descended on a tour of inspection and told him in no uncertain terms that the machine-guns would play an important role and he would be leading the gun team.135

At the beginning of September the whole tempo of preparations stepped up.136 Crookshank’s impression, after he and Macmillan had walked the ground together, was that the Loos battle they had taken part in during the previous September ‘didn’t start to be compared with this’.137 They were in ‘a glorified camp and depot for every kind of stores’, he recorded in an unsent letter. ‘One can hardly see a square yard of grass, it is absolutely thick and swarming with men, tents and horses…as for the guns they are past counting battery after battery of big ones…with mountains of ammunition and a light railway to supply it. It certainly was a revelation,’ he concluded, ‘and shows that we really have begun fighting now.’138

The Guards Division was deployed as part of Cavan’s XIV Corps on the south of the Somme front. Its mission was to move forward from the village of Ginchy, just to the south of Delville Wood, which still contained Germans, to the village of Lesboeufs to the north-east. On 11 September the detailed attack orders arrived.139 Crookshank held a Lewis gun parade ‘to tell off the different teams’. His own team consisted of a sergeant, four corporals and twenty-four men servicing four Lewis guns.140 On 12 September the 3rd Battalion moved up into the line, so that Lyttelton was posted only a few hundred yards to the right of Macmillan and Crookshank.141

It was Macmillan who went into action first. German machinegunners were positioned in an orchard on the northern edge of Ginchy. It was clear the moment the Guards started to advance they would be machine-gunned in the flank. On the night of 13 September de Crespigny ordered 4 Company, supported by two platoons of 3 Company, commanded by Macmillan, to clear the Germans out of the orchard.142 The attack took place in bright moonlight and in the face of heavy German fire; ‘it was very expensive, as they found better trenches and more Germans than expected’.

The next day, the 14th, ‘was terrible’. The 2nd Battalion’s trenches suffered a direct hit from a twenty-eight inch bomb. Many were buried alive and a company commander had to be relieved because of shell shock.143 ‘That day,’ wrote Lyttelton, ‘dawdled away.’ Towards evening the word came down that H-hour was 6.20 a.m. the next day. ‘Action,’ Lyttelton recorded. ‘Changed into thick clothes, filled everything with cigarettes. Put on webbing equipment. Drank a good whack of port. Looked to the revolver ammunition.’ They moved into position that night. It was bitterly cold. They looked ‘out into the moonlight beyond into the most extraordinary desolation you can imagine’. ‘The ground,’ Lyttelton wrote, ‘is like a rough sea, there is not a blade of grass, not a feature left on that diseased face. Just the rubble of two villages and the black smoke of shells to show that the enemy did not like losing them…the steely light of the dawn is just beginning to show at 5.30.’

This moonscape, devoid of landmarks, was to prove a terrible problem. Officers had their objectives clearly and neatly drawn in on the maps: first the Green Line, then the Brown Line, on to the Blue Line and finally crossing the Red Line to victory. Yet it was impossible to tell where these map lines fell on the real terrain. This sense of dislocation was made worse for the 3rd Battalion because of a tactical manoeuvre. Boy Brooke deployed his men too far to the right, intending that the Germans, expecting an attack in a straight line, would miss with their initial artillery strike. At 6 a.m. the British artillery opened up, the German guns replying within seconds. To the great satisfaction of Brooke and Lyttelton, the shells rained down on their former position, missing their new position completely. The disadvantage of the move, however, was that the 3rd Battalion had to make a dog-leg to the left once the attack had started. At 6.20 a.m. they went over the top.144

The advance was chaotic. Because the front was so narrow, both the 2nd Battalion and their next-door neighbours, the 3rd Battalion, were supposed to follow battalions of the Coldstream Guards into the attack. Within yards they had both lost all sense of direction. The three battalions of Coldstream Guards lurched off to the left. It was thus very difficult for the Grenadiers to fix their own position. They then discovered that the Germans had created an undetected forward skirmish line that, although it was completely outnumbered, ‘fought with the utmost bravery’. The 2nd Battalion found themselves caught in a ‘German barrage of huge shells bursting at the appalling rate of one a second, [they] were shooting up showers of mud in every direction and the noise was deafening. All this in addition to fierce rifle fire, which came from the right rear.’145 The German skirmishers succeeded in slowing down and breaking up the British formation before they were overwhelmed. Lyttelton and Brooke ‘flushed two or three Huns from a shell hole, who ran back. They did not get far.’ ‘I have,’ wrote Lyttelton after the battle, ‘only a blurred image of slaughter. I saw about ten Germans writhing like trout in a creel at the bottom of a shell hole and our fellows firing at them from the hip. One or two red bayonets.’

Macmillan was wounded in the knee as they tried to clear these lines. He kept going. Although the battalion passed through the barrage, it immediately ‘came under machine-gun fire from the left front and rifle fire from the right rear. Instead of finding itself…in rear of Coldstream, it was suddenly confronted by a trench full of enemy. This was the first objective, which the men naturally imagined had been taken by the Coldstream.’ They were deployed in artillery formation instead of in line, marching forward under the impression that two battalions of Coldstream Guards were in front of them. To approach the trench with any prospect of success, ‘it was necessary to deploy into line, and in doing this they lost very heavily’. During this manoeuvre Macmillan was shot in the left buttock.146 It was a severe wound: he rolled into a shell hole and dosed himself with morphine.

Crookshank was equally unlucky. His Lewis guns were doing good work.147 At about 7 a.m. he was just getting up to push forward once more when a high-explosive shell burst about eight yards in front of him. ‘I felt,’ he later remembered, ‘a great knock in the stomach and saw a stream of blood and gently subsided into a shell hole.’ He was in a perilous position: the shallow shell hole did not provide good cover. If any more shells landed near by he would be sure to be killed. He was saved by his orderly, who crawled to another shell hole and found a corporal, wounded in the head but fit enough to help. Between them the orderly and the corporal managed to carry Crookshank to a better hole, ‘where there were rather fewer shells dropping’. Like Macmillan Crookshank dosed himself with morphine and he and the corporal lay in their waterproof sheets. His orderly went back towards the British lines for help. They lay there for about an hour before the stretcher bearers arrived to evacuate them. Crookshank was conscious but mutilated: the shell had castrated him. Eventually he was taken back towards Ginchy. It was a nightmarish journey.148 Macmillan’s evacuation had been equally nightmarish. He crawled until he was rescued and had no medical attention for hours. Even when he was picked up by medical orderlies, heavy shelling forced him to abandon his stretcher and scuttle back towards safety.149 Although they had each escaped death by a fraction and reached field hospitals without being hit again, both were horribly wounded.

Although it was no longer of much interest to either Macmillan or Crookshank, the whole Guards Division was also in deep trouble. On its right the 6th Division had made no progress whatsoever. The tanks over which Churchill had rhapsodized to a sceptical Lyttelton a year before made no impression on their first day of battle. As a result the Guards’ right flank was exposed to a German strongpoint called ‘the Quadrilateral’ that poured fire into it. Their own formation was breaking up under a combination of German fire and the lack of any clear features in the terrain. There were no longer Grenadiers, Coldstreamers, Scots or Irish; they were mixed up together. Small units of men led by charismatic leaders were engaged increasingly in freelance actions. Lyttelton was one such freelancer. Spotting that a gap was opening up between the Coldstream Guards, who were veering to the left, and the Grenadiers, who were trying to shore up the right, he led about a hundred men forward to try and plug their front. His party of Grenadiers caught up with the Coldstreamers, but instead of repairing the front they were simply dragged along by the Scottish regiment, losing contact with their own battalion.