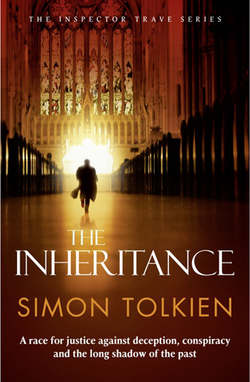

Читать книгу The Inheritance - Simon Tolkien - Страница 12

CHAPTER 5

ОглавлениеSasha stepped out from behind the back gate of New College and looked around. Silas was nowhere in sight. She’d known instinctively that he’d try to follow her, although she still couldn’t understand his apparent infatuation. It repelled her, and she wished she could leave the manor house and never see its new owner again. Perhaps she should. In truth she was close to giving up on finding the codex. In the last five months, she’d turned the leaves of every manuscript that John Cade owned, but nothing had fallen out. She’d stared into every recess, tapped every wall, and found nothing – only the diary secreted in the hollow base of the study bookcase that she’d discovered two days ago.

Sasha held the book close to her as she hurried through a network of narrow cobbled lanes, turning left and right, apparently at random. She remembered her excitement when she first found it. The study had been dark apart from her torch, and for a moment she felt as if Cade was there, watching her from the armchair where he used to sit, slowly rotating his thick tongue around his thin lips as he turned vellum pages one by one. Sasha had never been a superstitious person, but still she’d shivered and hurried away with the book to study it in the privacy of her room. Pausing for a moment to take a key out of her pocket, Sasha remembered the disappointment she’d felt as the first grey light had filtered through her window and she’d realized that the diary had taken her no nearer to the object of her search. She felt certain now that the old bastard had had the codex, but she still had no idea where it was. It was a secret that he’d taken with him to the grave. Unless her father could help. He was her last chance.

Sasha had stopped outside a tall old house that had clearly seen better days. The paint was cracked and dirty, and a row of bells by the door pointed to multiple occupation. But she didn’t press any of them. Instead she used her key to unlock the door, and then climbed four flights of a steep, uncarpeted staircase to the very top of the house, knocked lightly, and went in.

A white-haired man in a threadbare cardigan sat in the very middle of a battered leather sofa in the centre of the room. He looked at least ten years older than his real age of sixty-seven. His whole body was painfully thin, his face was deeply lined, and he sat very still except for the hands that trembled constantly in his lap. In the corner, a violin concerto that Sasha didn’t recognize was playing on a gramophone balanced precariously on two towers of books. Everywhere in the room were similar piles, and Sasha had to navigate a careful path between them to reach her father. She arrived just in time to stop his getting to his feet. Instead, she kissed him awkwardly on the crown of his head and then went over to a rudimentary kitchen area beside the single dirty window and began making tea.

‘How have you been?’ she asked.

‘Not bad,’ said the old man just like he always did, speaking in the hoarse whisper that represented all that was left of his voice after the throat cancer he had fought off three years before. Now it was Parkinson’s disease that he was up against, and Sasha wondered how long his ravaged frame would hold out. She loved her father and constantly wished that he would allow her to do more, but he was obstinate, holding on fiercely to what was left of his independence.

‘You’ve brought something,’ he said, looking down at the bag that Sasha had left on the sofa.

‘Yes, it’s Cade’s diary. I found it hidden in his study. It’s only for five years though. From 1935 through to 1940. Nothing after that. I don’t know whether he stopped writing it or whether the next one’s hidden somewhere else.’

‘It was the war,’ said the old man. ‘Professor Cade became Colonel Cade, remember? No more time for autobiography.’

‘You’re probably right. The book’s pretty interesting, though. Except that there’s nothing in it about what he did to you. Look, here.’ Sasha opened the book and pointed to a series of entries dating from late 1937. ‘Anyone reading this would think that he won that professorship on merit. It’s vile. He called himself a historian, and yet he spent his whole life falsifying history. He knew you were going to win, and so he fabricated that story about you and that student.’

‘Higgins. He wasn’t very attractive.’ Andrew Blayne smiled, trying to defuse his daughter’s anger.

‘I thought I could get you back your good name.’

‘I know you did. But it doesn’t matter now. It’s all ancient history.’

‘It matters to me.’ Sasha’s voice rose as her old sense of outrage took over. She felt her father’s humiliation like it had happened only yesterday. Cade had persuaded one of his rival’s pupils to allege a homosexual relationship and the mud had stuck. Andrew Blayne had lost the contest for the chair in medieval art history and had then been forced by his college to resign his fellowship. Since then he had supported himself through poorly paid private tutoring and temporary lecturing jobs at provincial universities, until ill health had put a stop even to that.

His wife, Sasha’s mother, was a strict Roman Catholic and had chosen to believe every one of the scurrilous allegations against her husband. She’d left him in his hour of need, taking their five-year-old daughter with her, and had then stopped the girl from seeing her father for most of her childhood. Sasha had always found this cruelty harder to forgive than all her mother’s neglect, and Andrew Blayne had remained the most important man in his daughter’s life.

‘Clearing my name wasn’t the main reason why you ignored all my objections and went to work for that man, was it, Sasha?’ said Andrew reflectively, as he stirred the tea in his chipped mug. He noticed how Sasha had filled it only halfway to the top to avoid the risk of his spilling hot tea on his trousers. It suddenly made him feel like an old man.

‘You wanted to find the Marjean codex. Just like I did years ago. Because you thought it would lead you to St Peter’s cross,’ he went on when she did not answer. ‘You should be careful, my dear. You’re not the first to have followed that trail. Look what happened to John Cade.’

‘That’s got nothing to do with the codex,’ said Sasha, sounding almost annoyed. ‘Cade’s son killed him. He’s on trial at the Old Bailey right now, and I’ve got to give evidence next week. Don’t you ever read the newspapers?’

‘Not if I can avoid it. And plenty of innocent people get put on trial for crimes they didn’t commit, Sasha. They get convicted too.’

‘Not this one. The evidence is overwhelming. But look, I didn’t come here to talk about Stephen Cade’s trial.’

‘You came here to talk about the codex.’

‘Yes.’ Sasha’s voice was suddenly flat, full of her disappointment over all her fruitless searches of the last few weeks.

‘I’ll tell you again. I think you should leave it alone.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because the codex, the cross – they should be yours. He stole everything from you.’

‘No, he didn’t, Sasha. I could have looked for the cross if I’d wanted to, but I didn’t. I chose not to.’

‘With no money?’ said Sasha passionately. ‘What could you do after he’d taken your livelihood away?’

The old man didn’t answer. He looked up at his daughter and smiled, before using both hands to contrive a sip of tea from his mug. But Sasha wouldn’t let it go.

‘I want to make it all up to you, Dad. Can’t you see that?’

‘I know you do, Sasha. But can’t you see that I don’t need objects? They mean nothing to me any more.’

‘I don’t believe you. Not this object.’

Not for the first time her father’s quiet stoicism grated on Sasha. It was beyond her comprehension that he could be so indifferent to what had been taken from him. Did he know more than he was saying? about Cade’s death? about the codex? and the cross? Suspicion creased her brow.

‘Look, I can’t even hold a cup of tea properly in my hand,’ said Blayne, gesturing with his shaking hand.

‘I know,’ she said. ‘I know.’ She felt foolish for a moment, ashamed of herself, looking down at her father’s ravaged body. She felt as if her long, fruitless search for codex and cross had started to make her see shadows in even the brightest corners.

‘I just want to have you and for you to be happy. That’s all,’ said Blayne.

It was hard to resist the appeal in his quavering voice or the tears glistening in his eyes, but Sasha’s face hardened, and she turned away from her father. Her jaw was set, and her lips folded in on themselves. She looked almost ugly.

‘I have to find it,’ she said quietly. ‘I’ve gone too far to stop now.’

Father and daughter looked deep into each other’s eyes for a moment before Andrew Blayne let go of Sasha’s sleeve and allowed his head to fall back against the sofa. He seemed to concentrate all his attention on a stain on the corner of the ceiling, and he kept his gaze fixed there even when he started speaking again.

‘Perhaps you’re wasting your time,’ he said. ‘Perhaps Cade never even had the codex.’

‘But I know he did,’ said Sasha passionately. ‘That’s why this diary is so important. Look, let me show it to you. You remember that he supposedly hired me to help him with research for his book on illuminated manuscripts?’

‘The magnum opus.’

‘Exactly. But he didn’t really care about that at all. He was obsessed with St Peter’s cross. He kept sending me to this library and that, looking for clues. But it was a wild-goose chase, and I think he half-knew that deep down. He was like a man who’s followed a trail to its logical end and found nothing there. He goes back, taking every side turn that he passed before but without any faith that they’ll lead anywhere.’

‘And he needed you because he couldn’t do his own research. Because he wouldn’t go out.’

‘Yes, he was always frightened,’ said Sasha. ‘But the interesting part was that he was always looking for the cross in any place except the one where it ought to be.’

‘In Marjean?’

‘Yes. It was like he already knew it wasn’t there. I tested him once. I showed him the John of Rome letter. It was a risk that he’d connect me with you, but I don’t think he did. I said that I’d found a copy in the Bodleian Library. But he wasn’t interested. He said it was a false trail. A waste of time.’

‘I remember you telling me that,’ said the old man, becoming increasingly interested in spite of himself. ‘I was the one who showed him the letter back in 1936 when I thought we were friends. He pretended not to be interested then too.’

‘Except that he was,’ said Sasha excitedly, pointing to an entry in the diary. ‘Here it is. 13 May, 1936. He’s copied out the whole of your translation, word for word.’ Sasha held up the yellowed document covered with spidery blue handwriting that she’d snatched from Silas in the car. ‘Here’s your copy and that’s his. They’re the same.’

Blayne took the manuscript in his trembling hand and began to read it aloud. The hoarseness seemed to go out of his voice, and Sasha felt herself transported back five hundred years, out of her father’s disordered attic room in Oxford to a wood-panelled library in the Vatican.

Another old man in a black monk’s habit was writing a letter, dipping his quill in the inkwell at the top of his sloping mahogany desk. The sunshine sparkled on the Tiber and illuminated the parchment across which his old bony hand was moving steadily from side to side.

My dear brother in Christ,

Let me tell you then what I know of the cross of Saint Peter. It has long been lost, but is perhaps not destroyed. Perhaps you will one day see what I have never found.

Certain it is that the cross was made from a fragment of the true cross on which Our Lord suffered. Blessed Saint Peter, our first Holy Father, wore it when he took ship and crossed the great sea to spread the word of God. And he gave it to Tiberius Maximus, a citizen of this town and a good Christian before he, Peter, suffered death at the hands of the unbelievers. The people of God kept the holy relic safe through centuries of war and persecution, until it passed out of recorded history at the time of the invasions from the North, when this holy city was sacked by the barbarians.

Yet I have long believed that the cross survived and that it is the same as the famous jewelled cross that the great king Charlemagne kept in his royal chapel at Aachen in the eighth century. Many years ago I was working in the French king’s library in the city of Paris when I came upon an inventory of Charlemagne’s treasury made by a Frankish scribe. I attach a copy, and you will see that he speaks of the cross of Charlemagne as being the holy rood of Saint Peter made from the wood of the true cross.

It was adorned with gems, the like of which the world has never seen before or since. The great diamond at the centre of the cross was said to be the same white stone that Caesar once gave to Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, to seal their illicit union, and the four red rubies were taken from the iron crown of Alexander the Great. The Franks believed that the cross had magical powers. Charlemagne used it on feast days to heal his sick subjects. It was truly one of the wonders of the world.

My brother, I have travelled in many lands during my long life, and I have never found any other written record of the cross of Saint Peter. I had thought that perhaps it was lost when the pagans came into France four hundred years ago, but I do not now believe this to be true. There are men that I have spoken to in the city of Rouen who say that the monks of Marjean kept the cross of Charlemagne in a reliquary behind the high altar of the abbey church for generations, until an unsuccessful attempt was made to steal it and the cross was hidden.

The fate of the community at Marjean was no different than that of so many of the other monasteries of France. The great plague that many called the Black Death came there out of the east in the year of our Lord 1352, and there appear to have been no survivors. Marjean is indeed a desolate place, and I have taken no pleasure from my visits there. Some of the monastic library was preserved in a château nearby, but I found no record of the cross there or anywhere else. Only this. I passed through the town once more last year and found an old man living in the ruins of the monastery. He said that his father’s uncle was one of those monks killed by the great plague and that his father had told him when he was a child that the hiding place of the cross had been recorded in a book made by the monks. I asked the old man many questions about the book, and I formed the opinion that he was speaking of the holy Gospel of Saint Luke. I now feel sure that he was referring to the famous Marjean codex of which you will have doubtless heard yourself. But it too is missing, and I am no nearer to finding the cross of Saint Peter, if it does indeed still exist.

I am old in years, and I must turn away from the love of this world and make myself ready for the next. I leave to you this account, which is all that I know of Saint Peter’s cross.

May God be with you.

Andrew finished reading and handed the paper back to his daughter.

‘I remember when I first read that,’ he said. ‘In Rome before the war. I had gone there with Cade for a conference, but he wasn’t in the library when I found it. There was this little room at the back, and I don’t even know why I went in there. It was more like a cupboard, really. Shelves of old dusty religious commentaries and John’s letter neatly folded between the leaves of one of them. God knows how it got there. All I know is that it had been there for a long, long time. I remember it was early evening and I sat at a table in the summer twilight and made this copy, and then I showed it to Cade back at the hotel. I was excited. The city was ablaze with fires. Mussolini had just conquered Abyssinia, and I had found John of Rome. But Cade made me lose belief. The cross was an old wives’ tale, he said. An invention of jewel-crazy adventurers. It was a waste of time to even think of it.’

‘But he was lying. You knew that already, Dad. After all, it was you who told me that he was in Marjean at the end of the war. You thought he’d gone after the cross.’

‘I said it was possible.’

‘Well, it was more than possible. That was what he was doing. This diary proves it.’

‘I thought you said that it stopped in 1940.’

‘It does. But by then he’d visited Marjean twice and was planning a third visit. The war stopped him, but then the end of it gave him the opportunity to take what he wanted by force. That was when he stole the codex.’

‘Who from?’

‘From a Frenchman called Henri Rocard, who was the owner of the château at Marjean up until 1944, when he and his family were all murdered. Allegedly by the Germans.’

‘But you say it was Cade who did it?’

‘Yes, I’m sure of it. Him and that man Ritter. Look, go back to John of Rome’s letter. See near the end, where he talks about visiting Marjean? He says that some of the monastic library was preserved in a château nearby.’

‘But he also says that he found no record of the cross there or anywhere else,’ countered Blayne, reading from the letter.

‘Perhaps he didn’t look in the right places,’ said Sasha. ‘Cade realized early on that that was the most important sentence in the whole document. He says so in his diary. The year after you found the letter he went to Marjean and visited the château there. Henri Rocard was away from home, but Cade spoke to the wife. He describes her as proud and rude.’

‘Is that all?’ asked Blayne, laughing.

‘Pretty much. She didn’t invite him in. Said she knew nothing about the codex. Cade didn’t believe her, of course.’

‘So what did he do?’

‘He went to the records office in Rouen and settled down to do some research.’

‘On the Rocard family.’

‘Yes. And he got lucky. Not to begin with, but he was persistent.’

‘Always one of the professor’s qualities.’

‘He had no qualities. Look, let me tell you what’s in the diary, Dad,’ said Sasha impatiently. ‘There was no reference to the codex in the first place he looked. Land deeds and wills and the like from before John of Rome’s time right up until the Revolution. But then in 1793 there was something. Robespierre and the Jacobins were in power in Paris, and it was the time of the Terror, soon after the king was guillotined. Government agents sent out from Paris arrested a Georges Rocard as a counter-revolutionary, and a record was made of a search of his château at Marjean. Cade copied part of the record into his diary. It says that the government agents found no trace of the valuable document known as the Marjean codex.’

‘Just like John of Rome, when he searched for it four centuries earlier,’ said Blayne, sounding unimpressed.

‘But that’s not the point,’ said Sasha. ‘What’s important is that there were people at the end of the eighteenth century who believed that the codex was in the château at Marjean. There must have been some basis for that.’

‘Maybe,’ said her father, still unconvinced. ‘What happened to Georges Rocard?’

‘He didn’t escape, I’m afraid. Almost no one did. He was guillotined in Rouen a few weeks after his arrest. But his family got away to England, and Georges’s eldest son returned to Marjean and the château when the monarchy was restored in 1815. After the Battle of Waterloo.’

‘And this Henri Rocard was a descendant of his?’

‘Yes. Cade went back to the château, and this time Henri Rocard was there in person.’

‘Proud and rude like his wife?’

‘Worse, apparently. Rocard told Cade that he knew nothing about the codex, and when Cade persisted, Rocard and his old manservant set the dogs on him.’

‘Did they bite?’

‘I don’t know. The point is that the reception he got from Madame Rocard and then from her husband convinced Cade that they had the codex.’

‘So what did he do?’

‘He wrote to Henri Rocard offering to buy it. There’s a copy of his letter in the diary. He pointed out that the château was in a state of serious dilapidation and that the money could be used to carry out all the necessary repairs. But he got no reply. He wrote again but still heard nothing, and he was just about to go to Marjean again when the war broke out.’

‘So he was cut off from the object of his desire for more than four years,’ said Blayne musingly. ‘The professor must have been a very frustrated man by the time D-Day came around.’

‘Exactly,’ said Sasha. ‘We know he went to that area in 1944 and the whole Rocard family died. I believe Cade killed them, and that he stole the codex at the same time. He’d already been there and done that, and that’s why he always acted like he was so uninterested in Marjean and the codex.’

‘So where is the codex, if you’re so certain he had it?’ asked Blayne.

‘I don’t know. I thought you could help me. I’ve looked everywhere.’ The frustration was back in Sasha’s voice.

Blayne looked hard at his daughter and shook his head.

‘Leave it, Sasha. It’s dangerous. I can feel it. The man spent almost half his life searching for something, and now he’s dead. It’s not the first time he was shot, either. Somebody tried to kill him in France three years ago. You tell me it’s got nothing to do with the cross, but I’m not so sure. Let it die with him. Let it go.’

‘That’s easy for you to say,’ she blurted out and then immediately turned away from her father, trying to clear her mind. Again she had that same fleeting sense that he knew more than he was saying. Why hadn’t he been more surprised by her revelations – more excited? No one had suffered more at the hands of John Cade than her father. No one except Cade knew more about the codex. The codex and the cross.

‘I don’t understand why you’re so calm about all this, so accepting,’ she said, challenging him.

‘Because I’m old,’ he said. ‘Old before my time. Can’t you see that, Sasha?’

Blayne put his hand out towards his daughter, but she turned away and walked over to the window. She looked down into the stony courtyard, and her resolve hardened. ‘I’ll leave the diary here,’ she said. ‘You can call me if you think of anything. I’ll find the codex. And after that I’ll find the cross.’

‘And then?’ asked Blayne, looking up sadly at his daughter. ‘What happens then, Sasha?’

She didn’t answer. Just laid her hand for a moment over her father’s shaking hand and then walked out of the door.