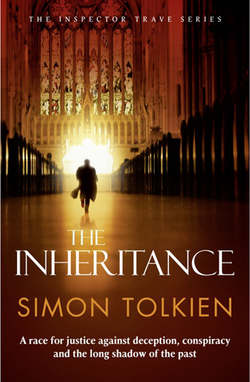

Читать книгу The Inheritance - Simon Tolkien - Страница 5

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

ОглавлениеThe controversial executions of Derek Bentley and Ruth Ellis in the 1950s increased public pressure in the United Kingdom for the abolition of hanging, and this was answered in part by the passing of the Homicide Act in 1957, which limited the imposition of the death penalty to five specific categories of murder. Henceforward only those convicted of killing police officers or prison guards and those who had committed a murder by shooting or in the furtherance of theft or when resisting arrest could suffer the ultimate punishment. The effect of this unsatisfactory legislation was that a poisoner or strangler acting with premeditation would escape the rope, whereas a man who shot another in a fit of rage might not. This anomaly no doubt helped the campaign for outright abolition, which finally reached fruition with the passage of the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act in 1965.

Death sentences were carried out far more quickly in England in the 1950s than they are in the United States today. A single appeal against the conviction but not the sentence was allowed, and, if it failed, the Home Secretary made a final decision on whether to exercise the royal prerogative of mercy on behalf of the Queen, marking the file ‘the law must take its course’ if there were to be no reprieve. There was often no more than a month’s interval between conviction and execution. Ruth Ellis, for example, spent just three weeks and three days in the condemned cell at Holloway Prison in 1955 before she was hanged by Albert Pierrepoint for the crime of shooting her boyfriend.

There was thus very little time available for lawyers or other interested parties trying desperately to uncover new evidence that might exonerate a client sentenced to die. They were quite literally working against the clock.