Читать книгу Titian - Sir Claude Phillips - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеTitian is one of the greatest, most influential painters in Italian art. Though the names of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, figures so rarefied by centuries of adulation that we have all but lost sight of the power of their works, may ring more loudly to twenty-first century ears than that of the Venetian painter; though Raphael may excel him in his ethereal coolness and his perfect balance in both spirit and hand, Titian stands out instead for the broad scope of his work, flowing with the life-blood of humanity, rendering him more the poet-painter of the world and worldly creatures. When we think of the Entombment in the Louvre, the Assunta, the Retable of the Madonna Pesaro, the remnants of the Saint Peter Martyr, can we possibly discount or minimize his contribution to art and Western culture? Rarely do the pomp and splendour of a painter’s most representative achievements combine so consistently with a dignity and simplicity that rest within the bounds of nature. The sacred art of few other sixteenth-century painters has to an equal degree influenced the course of art history and moulded the style of the world as that of Titian, whose great ceremonial altarpieces manifest a passion that exaggerates only to better express its truth.

At least in the history of Italian art, Titian, if we are to treat him fairly, stands out as one of the top and maybe even the most important of portrait painters, successfully treating both men and women. Of other great practitioners in this genre, Leonardo evokes a truly unsettling power of fascination over his viewer, while Raphael and Michelangelo, along with Giorgione, mix wonderfully in the portraits of Sebastiano del Piombo. Let’s go back to Giorgione; he gave his subjects a poetic glamour by painting in an embellished but very realistic style. Lorenzo Lotto also has some good portraits, manifesting a real tenderness through his style of interpretation, uniquely combining his subjective feelings with a universal objectivity, the one rendering the other poetic. Other great Italian portrait painters include Moretto da Brescia, whose style is marked by tones of melancholy and aristocratic charm, and Giovanni Battista Moroni, who possessed the marvellous power to unite the spiritual and material aspects of human individuality without overdoing it. But even those who adore the aforementioned artists, if they wish to maintain any semblance of justice or seriousness in their study of art history, must recognize Titian’s style of portraiture as the strongest, most developed and most unique, at least with respect to the sheer number of artists his style has inspired.

His developments in the realm of landscape painting remain just as foundational as those of portraiture. Here, he had many great precursors and teachers whose lessons he synthesized into a groundbreaking whole. Until Claude Lorrain much later, none succeeded in entirely mimicking Titian’s manner of expressing the fullness of natural beauty without too strictly adhering to a factual, limited realism. Giovanni Bellini from his earliest beginnings in Padua displayed, unlike his great brother-in-law Mantegna, unlike the Squarcionesques and the Ferrarese, the true gift of the landscape painter. Atmospheric conditions invariably formed an important element of his compositions, shown clearly in the chilly solemnity of the landscape in his great Pietà of the Pinacoteca di Brera, the ominous sunset in the Agony in the Garden at the National Gallery, the cheerful all-pervading glow of the beautiful Sacred Conversation of the Uffizi and the mysterious illumination of the late Baptism of Christ at the Church of Santa Corona in Vincenza. Moving to Giorgione’s landscapes leads us into a perilous discussion of a quite fascinating subject, so various are his techniques even in the few well-established examples we have of his art, so exquisite an instrument of expression, so complete an illustration of the complex moods of his characters. But even based on the masterworks of his mature period such as the great altarpiece of Castelfranco, The Tempest[1] in the Galleria dell’Academia and the Three Philosophers in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Giorgione’s landscapes still have a slight flavour of the late medieval period just merging into full perfection. In his early period, it was Titian who would fully develop the Giorgionesque landscape, as in the Three Ages of Man, Sacred and Profane Love, and The Rustic Concert. Having learned from the best, he went on alone to surpass his masters in his radiantly beautiful representations of earth and sky that environ the figures of The Offering to Venus, the Bacchanal on Andros and Bacchus and Ariadne. These rich backgrounds of reposeful beauty reflect and build on those which enhance the finest of his Holy Familes and Sacred Conversations. More than the dramatic intensity and academic amplitude of its figures, it was the ominous grandeur of its landscape which won the Saint Peter Martyr its universal and well-documented fame. The same intimate relationship between landscape and figures reappears in the later Jupiter and Antiope (Venus of the Pardo) of the Louvre, marking a return to Giorgionesque repose and communion with nature. This can also be found in the later Rape of Europa, where the rainbow hues and bold sweep of the landscape recall the much earlier Bacchus and Ariadne. In the late masterpiece in monotone Shepherd and Nymph of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the sensuousness of the early Giorgionesque time reappears with an even greater force, tempered, as in the early days, by the imaginative temperament of the poet, and above all by the solemn atmosphere of mystery belonging to Titian’s final years.

Though Titian cannot boast the universality in art and science which lured da Vinci into a countless number of parallel pursuits, the vast scope of Michelangelo’s media and vision, or even the all-embracing curiosity of Albrecht Dürer, as a painter, he certainly covered more ground than any other master of the sixteenth century. While in more than one branch of his art Titian stood forth supreme and without rival, in the realm of monumental, decorative painting he yielded the palm to his younger rivals Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, who showed themselves more practised and more successfully daring in this particular branch.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Pope Paul III Farnese (head uncovered), 1543.

Oil on canvas, 106 × 85 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi, c. 1517.

Oil on panel, 154 × 119 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Pope Paul III and his Nephews (Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese), c. 1545–1546.

Oil on canvas, 202 × 176 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Ippolito de’ Medici, c. 1532–1534.

Oil on canvas, 139 × 107 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

To find another instance of such supreme mastery of the brush, one must go to Antwerp, the great merchant city of the North as Venice was of the South. Rubens, who could arguably be described as the Flemish Titian, and who indeed owed much to his Venetian predecessor, though far less than did his own pupil Van Dyck, was during the first forty years of the seventeenth century on the same pinnacle of supremacy that the Cadorine master had occupied for a much longer period during the Renaissance. He too was without rival in the creation of those vast altarpieces that made famous the churches that owned them; he too was the finest painter of landscape of his time, using it as an accessory to the human figure. Moreover, he was a portrait painter who, in his greatest efforts – those sumptuous and almost truculent portraits d’apparat of princes, nobles and splendid dames – knew no superior, though his contemporaries were Van Dyck, Frans Hals, Rembrandt and Velázquez. Rubens united nature and man in a more demonstrative, seemingly closer embrace, drawing from a more exuberant vigour, but taking from the very closeness some of the stain of earth. Titian, though he was at least as genuine a realist as his successor, and one less content with the mere exterior of things, was filled with the spirit of beauty which was everywhere; in the mountain home of his birth as well as in the radiant home of his adoption, in himself as in his everyday surroundings. His art always demonstrated, even in its most human and least aspiring phases, the divine harmony, the suavity tempering natural truth and passion that distinguishes Italian art of the great periods from the finest art from elsewhere.

The relation between the two masters – both in the first line of the world’s painters – was much like that between Venice and Antwerp. The apogee of each city represented in its different way the highest point that modern Europe had reached of physical well-being and splendour, of material as distinguished from mental culture. Reality, with all its warmth and all its truth, in Venetian art was still reality. But it was reality made at once truer, wider and more suave by the method of its presentation. Idealisation, in the narrower sense of the word, could add nothing to the loveliness of such a land, to the stateliness, the splendid sensuousness devoid of the grosser elements, to the genuine naturalness of such a way of life. Art itself could only add to it the right accent, the right emphasis, the larger scope in truth, the colouring and illumination best suited to give the fullest expression to the beauties of the land, to the force, character and warm human charm of the people. This is what Titian, one of the best among his contemporaries of the greatest Venetian time, did with an incomparable mastery to which, in the vast field which his productions cover, it would be vain to seek for a parallel.

Other Venetian artists may, in one way or another, more irresistibly enlist our sympathies, or may shine out for the moment more brilliantly in some special branch of their art. Frequently, though, we still find ourselves invariably comparing them to Titian, not Titian to them; taking him as the standard for the measurement of even his greatest contemporaries and successors. Giorgione was of a finer fibre and, it could be said, more happily combined the subtlest qualities of the painter and the poet, in his creation of a phase of art of which the penetrating exquisiteness has never in the succeeding centuries lost its hold on the world. But then Titian, saturated with the Giorgionesque, and only marginally less the poet-painter than his master and companion, carried the style to a higher pitch of material perfection than its inventor himself had been able to achieve. The gifted but unequal Pordenone, who showed himself so incapable of sustained rivalry with our master in Venice, had moments of a higher sublimity that Titian did not reach until he came to the extreme limits of old age. This assertion is not a mere paradox, as the great Madonna del Carmelo at the Galleria dell’Academia and the magnificent Trinity in the sacristy of the Cathedral of San Daniele near Udine prove. Yet who would venture to compare him on equal terms to the painter of the Assunta, the Entombment and the Supper at Emmaus? Tintoretto, at his best, had lightning flashes of illumination, a titanic vastness, an inexplicable power of perturbing the spirit and placing it in his own atmosphere, which may cause the imaginative not altogether unreasonably to put him forward as the greater figure in art. All the same, if it were necessary to make a definite choice between the two, who would not uphold the saner and greater art of Titian, even though it might leave us nearer to reality, though it might conceive the supreme tragedies, not less than the happy interludes, of the sacred drama, in the purely human spirit and with the pathos of earth? A not dissimilar comparison might be made between the portraits of Lorenzo Lotto and those of Titian. No other Venetian painter had that peculiar imaginativeness of Lotto, which caused him to unconsciously infuse into it much of his own tremulous sensitiveness and charm, while seeking to penetrate into the depths of human individuality. In this way no portraits of the sixteenth century provide so fascinating a series of riddles. Yet in deciphering them it is necessary to take into account the peculiar temperament of the painter himself, as well as the physical and mental characteristics of the sitter and the atmosphere of the time.[2]

Finally, in the domain of pure colour some will deem that Titian has serious rivals in those Veronese who became Venetians: the elder Bonifazi and the younger Paolo Veronese. That is to say, there will be found lovers of painting who prefer a brilliant mastery over contrasting colours in frank juxtaposition to a relatively restricted palette, used with more subtle, if less dazzling art than theirs, and resulting in a deeper, graver richness. That is, a more significant beauty, if less stimulating in gaiety and variety of aspect. No less a critic than Morelli himself pronounced the elder Bonifazio Veronese to be the most brilliant colourist of the Venetian school, and Dives and Lazarus of the Galleria dell’Academia and the Finding of Moses at the Brera are at hand to give solid support to such an assertion.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Aretino, 1545.

Oil on canvas, 96.7 × 77.6 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

Giovanni Bellini, The Doge Leonardo Loredan, c. 1501–1504.

Oil on poplar, 61.6 × 45.1 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Doge Marcantonio Trevisani, 1553.

Oil on canvas, 100 × 86.5 cm. Szépmūvészeti Múzeum, Budapest.

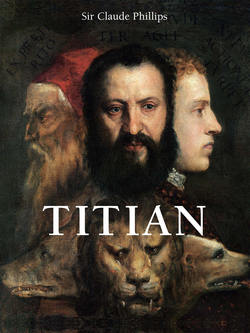

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Self-Portrait, c. 1562–1564.

Oil on canvas, 96 × 75 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

In some ways Paolo Veronese may, without exaggeration, be held as the greatest virtuoso among colourists, the most marvellous executant to be found in the whole range of Italian art. Starting from the cardinal principles in colour of the true Veronese, his precursors – painters such as Domenico and Francesco Morone, Liberale, Girolamo dai Libri, Cavazzola, Antonio Badile, and the rather later Brusasorci and Caliari – dared combinations of colour the most trenchant in their brilliancy as well as the subtlest and most unfamiliar. Unlike his predecessors, however, he preserved the stimulating charm while abolishing the abruptness of sheer contrast. This he did mainly by balancing and tempering his dazzling hues with huge architectural masses of a vibrant grey and large depths of cool dark shadow – brown shot through with silver. No other Venetian master could have painted the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine in the church of that name at Venice, the Allegory on the Victory of Lepanto in the Galleria dell’Academia, or the vast Nozze di Cana of the Louvre. All the same, this virtuosity, while it was in one sense a step in advance even of Giorgione, Titian, Palma, and Paris Bordone – constituting as it does a further development of painting from the purely decorative standpoint – must appear just a little superficial, a little self-conscious, by the side of the nobler, graver, and more profound, if in some ways more limited methods of Titian. With him, as with Giorgione, and indeed with Tintoretto, colour was above all an instrument of expression. The main effort was to realise the subject presented with splendid and penetrating truth, and colour in accordance with the true Venetian principle was used not only as the decorative vesture, but as the very body and soul of painting, as it is in nature.

To put forward Paolo Veronese as purely the dazzling virtuoso would be to show a singular ignorance of the true scope of his art. He could rise as high in dramatic passion and pathos as the greatest of them all on occasions; but these are precisely the times at which he most resolutely subordinated his colour to his subject and made the most poetic use of chiaroscuro. This can be seen in the great altarpiece The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian in the church of that name (San Sebastiano in Venice), Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata on a ceiling compartment of the Academy of Arts at Vienna, and the wonderful Crucifixion in the Louvre. Yet in this last piece the colour is not only in a singular degree interpretative of the subject, but at the same time technically astonishing, with certain subtleties of unusual juxtaposition and modulation, delightful to the craftsman, which are hardly seen again until the late nineteenth century. So that here we have the great Veneto-Veronese master escaping altogether from our theory, and showing himself at one and the same time profoundly moving, intensely significant, and admirably decorative in colour. Still, what was with him the splendid exception was with Titian, and those who have been grouped with Titian, the guiding rule of art. Though Titian remains the greatest Venetian colourist, he never condescended to vaunt all he knew, nor to select even the most legitimate of his subjects as a groundwork for bravura. He is the greatest painter of the sixteenth century simply because, being the greatest colourist of the higher order and in legitimate mastery of the brush second to none, he made the worthiest use of his unrivalled accomplishment. This was not merely to inspire applause due to his supreme pictorial skill and the victory over self-set difficulties, but above all to give the fullest and most legitimate expression to the subjects which he presented, and through them to himself.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Man with a Glove, c. 1520.

Oil on canvas, 100 × 89 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

1

Herr Franz Wickhoff in his now famous article “Giorgione’s Bilder zu Römischen Heldengedichten” (Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen: Sechzehnter Band, I. Heft) has most ingeniously, and upon what may be deemed solid grounds, renamed this most Giorgionesque of all Giorgiones after an incident in the Thebaid of Statius, Adrastus and Hypsipyle. He gives reasons which may be accepted as convincing for entitling the Three Philosophers, after a familiar incident in Book viii. of the Aeneid, “Aeneas, Evander, and Pallas contemplating the Rock of the Capitol.” His not less ingenious explanation of Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love will be dealt with a little later on. These identifications are all-important, not only in connection with the works themselves thus renamed, and for the first time satisfactorily explained, but as compelling the students of Giorgione partly to reconsider their view of his art, and, indeed, of the Venetian idyll generally.

2

For many highly ingenious interpretations of Lotto’s portraits and a sustained analysis of his art generally, Bernard Berenson’s Lorenzo Lotto should be consulted. See also Emile Michel’s article, “Les Portraits de Lorenzo Lotto,” in the Gazette des Beaux Arts, 1896, vol. I.