Читать книгу Titian - Sir Claude Phillips - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

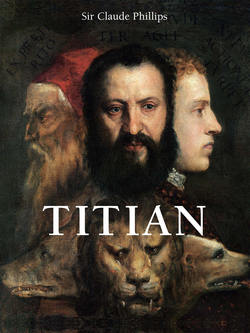

The Earlier Work of Titian

ОглавлениеTiziano Vecelli was born in the last quarter of the fifteenth century at Pieve di Cadore, a district of the southern Tyrol then belonging to the Republic of Venice. He was the son of Gregorio di Conte Vecelli and his wife Lucia. His father came from an ancient family of the name of Guecello (or Vecellio), established in the valley of Cadore. An ancestor, Ser Guecello di Tommasro da Pozzale, had been elected Podesta of Cadore as far back as 1321.[3] The name Tiziano would appear to have been a traditional one in the family. Among others we find a contemporary Tiziano Vecelli, who was a lawyer of note concerned in the administration of Cadore, keeping up a kind of obsequious friendship with his famous cousin in Venice. The Tizianello who in 1622 dedicated an anonymous Life of Titian known as Tizianello’s Anonimo to the Countess of Arundel, and who died in Venice in 1650, was Titian’s cousin thrice removed.

Gregorio Vecelli was a valiant soldier, distinguished for his bravery in the field and his wisdom in the council of Cadore, but not, it may be assumed, possessed of wealth or, in a poor mountain district like Cadore, endowed with the means of obtaining it. At the age of nine, according to Dolce in the Dialogo della Pittura, or of ten, according to Tizianello’s Anonimo, Titian was taken from Cadore to Venice to begin his painting studies. Whether he had previously received some slight tuition in the rudiments of the art, or had only shown a natural inclination to become a painter, cannot be ascertained with any precision. What is much more vital in our study of the master’s life-work is to ascertain how far the scenery of his native Cadore left a permanent impression on his landscape art, and in what way his descent from a family of hardy mountaineers and soldiers of a certain birth and breeding contributed to shape his individuality in its development to maturity. It has been almost universally assumed that Titian throughout his career made use of the mountain scenery of Cadore in the backgrounds of his pictures. However, except for the great Battle of Cadore itself (now known only in Fontana’s print, in a reduced version of part of the composition to be found at the Galleria degli Uffizi, and in a drawing of Rubens at the Albertina), this is only true in a modified sense. Undoubtedly, both in the backgrounds to altarpieces, Holy Families, and Sacred Conversations, and in the landscape drawings of the type so freely copied and adapted by Domenico Campagnola, we find the jagged, naked peaks of the Dolomites aspiring to the heavens. The majority of the time, however, the middle distance and foreground to these is not the scenery of the higher Alps, with its abrupt contrasts, monotonous vesture of fir or pine forests clothing the mountain sides, and its relatively harsh and cold colouring. It is the richer vegetation of the lower slopes of the Friulan Mountains, or beautiful hills bordering upon the overflowing richness of the Venetian plain. Here the painter found greater variety, greater softness in the play of light, and richness more suitable to the character of Venetian art. He had the amplest opportunities for studying these tracts of country, as well as the more grandiose scenery of his native Cadore itself in the course of his many journeys from Venice to Pieve and back, as well as in his shorter expeditions on the Venetian mainland. The extent to which Titian’s Alpine origin, and his early upbringing among impoverished mountaineers, may account for his excessive eagerness to reap all the material advantages of his artistic pre-eminence, for his unresting energy when any post was to be obtained or any payment to be got in, must be a matter for individual appreciation. Josiah Gilbert – quoted by Crowe and Cavalcaselle[4] – pertinently asks, “Might this mountain man have been something of a ‘canny Scot’ or a shrewd Swiss?” In the earning of money, Titian was certainly all this, but in the spending he was large and liberal, inclined to splendour and profusion, particularly in the second half of his career. Vasari relates that Titian was lodging in Venice with his uncle, an “honourable citizen”, who, seeing his great inclination for painting, placed him under Giovanni Bellini, in whose style he soon became an expert. Dolce, in his Dialogo della Pittura, gives Sebastiano Zuccato, best known as a mosaic worker, as his first master. He then makes him pass into the studio of Gentile Bellini, and thence into that of the caposcuola (founder) Giovanni Bellini. Dolce then asserted that Titian took the last and by far the most important step of his early career by becoming the pupil and partner, or assistant, of Giorgione, but this has never been confirmed. Morelli[5] would prefer to leave Giovanni Bellini out of Titian’s artistic descent altogether. However, certain traces of Gentile’s influence may be observed in the art of the Cadorine painter, especially in the earlier portraiture, but particularly in the methods of technical execution generally. On the other hand, no existing earlier works suggest the view that he was part of the inner circle of Giovanni Bellini’s pupils – one of the discipuli (disciples), as some of these were fond of describing themselves. No young artist painting in Venice in the last years of the fifteenth century could, however, entirely withdraw himself from the influence of the veteran master, whether he actually belonged to his following or not. Giovanni Bellini exercised upon the contemporary art of Venice and the Veneto an influence as strong as that of Leonardo on that of Milan and the adjacent regions during his Milanese period. The latter not only stamped his art on the works of his own special school, but fascinated in the long run the painters of the specifically Milanese group which sprang from Foppa and Borgognone; such men as Ambrogio de’ Predis, Bernardino de’ Conti and the somewhat later Bernardino Luini. Even Alvise Vivarini, the vigorous head of the opposite school in its latest quattrocento development, bowed to the fashion for the Bellinesque conceptions of a certain class when he painted the Madonnas of the Redentore and San Giovanni in Bragora in Venice, and the similar one now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Bernard Berenson was the first to trace the artistic connection between Vivarini and Lorenzo Lotto, who was to a marked extent under the influence of Giovanni Bellini in such works as the altarpiece of Santa Cristina near Treviso, the Madonna and Child with Saints, and the Madonna and Child with Saint Peter Martyr in the Naples Museum. In the Marriage of Saint Catherine at Munich, though it belongs to the early period, he is, both as regards exaggerations of movement and delightful peculiarities of colour, essentially himself. Marco Basaiti, who up to the date of Alvise Vivarini’s death was intimately connected with him, and so far as he could faithfully reproduce the characteristics of his incisive style, was transformed in his later years into something very like a satellite of Giovanni Bellini. Cima, who in his technical processes belongs rather to the Vivarini than to the Bellini group, was to a great extent overshadowed, though never, as some would have it, absorbed to the point of absolute imitation, by his greater contemporary.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Man with a Glove, 1517–1520.

Oil on canvas, 88 × 73 cm. Musée Fesch, Ajaccio.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), A Man with a Quilted Sleeve, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 81.2 × 66.3 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of a Man, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas, 76.5 × 62.8 cm. Smoking Room at Ickworth, Bury St. Edmunds.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of a Lady (“La Schiavona”), c. 1510–1512.

Oil on canvas, 119.9 × 100.4 cm. The National Gallery, London.

What may legitimately intrigue in both Giorgione and Titian’s early years is not so much that in their earliest productions they leant to a certain extent on Giovanni Bellini, but that they were so soon independent. Neither of them is in any existing work seen to have the same absolutely dependent relationship with the veteran quattrocentist which Raphael for a time had with Perugino, and which Sebastiano Del Piombo in his early years had with Giorgione. This holds good to a certain extent also of Lorenzo Lotto, who in the earliest known examples – such as the Saint Jerome of the Louvre – is already emphatically Lotto. As his art passed through successive developments, however, he still showed himself open to more or less enduring influences from elsewhere. Sebastiano del Piombo, on the other hand, great master as he undoubtedly was in every phase, was never throughout his career free of influence. First, as a boy, he painted the puzzling Pietà, which, notwithstanding the authentic inscription, Bastian Luciani fuit descipulus Johannes Bellinus (sic) is so astonishingly like Cima that, without this piece of documentary evidence, it would even now pass as such. Next he became the most accomplished exponent of the Giorgionesque manner, save perhaps Titian himself. Then, migrating to Rome, he produced, in a quasi-Raphaelesque style still strongly tinged with the Giorgionesque, that series of superb portraits which under the name of Sanzio have acquired a worldwide fame. Finally, surrendering himself body and soul to Michelangelo, he remained enslaved by the tremendous genius of the Florentine to the very end of his career, only unconsciously allowing, from the force of early training and association, his Venetian origin to reveal itself.

Giorgione and Titian were both born in the last quarter of the fifteenth century; Giorgione around 1477 and Titian approximately ten years later, although there is still an ongoing debate on that matter. Lorenzo Lotto’s birth is to be placed around the year 1480. Palma was born around 1480, Pordenone possibly around the years 1483–1484 and Sebastiano Del Piombo around 1485. This shows that most of the great protagonists of Venetian art during the earlier half of the cinquecento were born within a short period of about fifteen years – between 1475 and 1490.

It is easy to understand how the complete renewal brought about by Giorgione on the basis of Bellini’s teaching and example operated to revolutionise the art of his own generation. He threw open to art the gates of life in its mysterious complexity, in its fullness of sensuous yearning mingled with spiritual aspiration. The fascination exercised both by his art and his personality was irresistible to his youthful contemporaries; the circle of his influence increasingly widened, until it might almost be said that the veteran Gian Bellini himself was brought within it. With Titian and Palma the germs of the Giorgionesque fell upon fruitful soil, and in each case produced a vigorous plant of the same family, yet with all its Giorgionesque colour of a quite distinctive kind. Titian, we shall see, carried the style to its highest point of material development, and made a new thing of it in many ways. Palma, with all his love of beauty in colour and form, in nature as in man, had a less finely attuned artistic temperament than Giorgione, Titian or Lotto. Morelli called attention to that energetic element in his mountain scenes, which in a way counteracted the marked sensuousness of his art, save when he interpreted the charms of the full-blown Venetian woman. The great Milanese critic attributed this to the rustic origin of the artist, showing itself beneath Venetian training. Is it not possible that a little of this frank unquestioning sensuousness on the one hand, of this terre à terre energy on the other, may have been reflected in the early work of Titian, though it be conceded that he influenced far more than he was influenced?[6] There is undoubtedly in his personal development of the Giorgionesque an extra element of something much nearer to the everyday world than is to be found in the work of his prototype, and this almost indefinable element is peculiar also to Palma’s art, in which it endures to the end. Thus there is a singular resemblance between the type of his fairly fashioned Eve in the important Adam and Eve of his earlier period now in the Prado – once, like so many other things, attributed to Giorgione – and the preferred type of youthful female loveliness as it is to be found in Titian’s Three Ages in the National Gallery of Scotland. This can also be found in his Sacred and Profane Love (Medea and Venus) in the Borghese Gallery, in such sacred pieces as the Madonna and Child with Saints Ulfo and Brigida which is now called Virgin and Child with Saints Dorothy and George in the Prado Museum of Madrid, and the large Madonna and Child with four Saints in Dresden. In both instances we have the Giorgionesque conception stripped of a little of its poetic glamour but retaining unabashed its splendid sensuousness, which is thus made to stand out more markedly. We notice, too, in Titian’s works of this particular group another characteristic which may be styled Palmesque, if only because Palma indulged in it in a great number of his Sacred Conversations and similar pieces. This is the contrasting of the rich brown skin and the muscular form of a male saint, or of a shepherd of the uplands, with the dazzling fairness, set off with hair of pale or ruddy gold, of a female saint or fair Venetian doing duty as a shepherdess or a heroine of Antiquity. Are we to look upon such distinguishing characteristics as these as wholly and solely Titian of the early period? If so, we ought to assume that what is most distinctively Palmesque in the art of Palma came from the painter of Cadore, who in this case should be taken to have transmitted to his brother in art the Giorgionesque in the less subtle shape into which he had already transmuted it. But should not such an assumption as this, well founded as it may appear in the main, be made with all the allowances that the situation demands?

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Annunciation, c. 1519–1523.

Oil on wood, 179 × 207 cm. Il Duomo, Treviso.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Virgin and Child between Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Roch, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas, 92 × 133 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

When a group of young and enthusiastic artists, eager to overturn barriers, are found painting more or less together, it is not so easy to unravel the tangle of influences and draw hard-and-fast lines everywhere. One or two more modern examples may roughly serve to illustrate. Take, for instance, the friendship that developed between the youthful Bonington and the young Delacroix while they copied together in the galleries of the Louvre. One would communicate to the other something of the stimulating quality, the frankness, and variety of colour which at that moment distinguished the English from the French school; the other would contribute, with the fire of his romantic temperament, to the art of the young Englishman who was some three years his junior. And with the famous trio of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – Millais, Rossetti and Holman Hunt – who is to state ex cathedra where influence was received, where transmitted; or whether the first may fairly be held to have been, during the short time of their complete union, the master-hand, the second the poet-soul, the third the conscience of the group?

In days of artistic upheaval and growth such as the last years of the fifteenth century and the first years of the sixteenth, the milieu must count for a great deal. It must be remembered that the men who most influence a time, whether in art or letters, are just those who, deeply rooted in it, come forth as its most natural development. Let it not be doubted that when the first sparks of the Promethean fire had been lit in Giorgione’s breast, which, with the soft intensity of its glow, warmed into full-blown perfection the art of Venice, that fire ran like lightning through the veins of all the artistic youth. The blood of his contemporaries and juniors was of the material to ignite and flame like his own.

The great Giorgionesque movement in Venetian art was not a question merely of school, of standpoint, of methods adopted and developed by a brilliant galaxy of young painters. It was not alone that “they who were excellent confessed, that he (Giorgione) was born to put the breath of life into painted figures, and to imitate the elasticity and colour of flesh, etc.”[7] It was also that the Giorgionesque in conception and style was the outcome of the moment in art and life, just as the Pheidian mode had been the necessary climax of Attic art and Attic life aspiring to reach complete perfection in the fifth century B. C.; just as the Raphaelesque appeared the inevitable outcome of those elements of lofty generalisation, divine harmony, grace clothing strength, which, in Florence and Rome, as elsewhere in Italy, were culminating in the first years of the cinquecento. This was the moment, too, when – to take one instance only among many – the ex-Queen of Cyprus, the noble Venetian Caterina Cornaro, held her little court at Asolo, where, in accordance with the spirit of the moment, the chief discourse was always of love. In that reposeful kingdom, which could in miniature offer to Caterina’s courtiers all the pomp and charm without the drawbacks of sovereignty, Pietro Bembo wrote for “Madonna Lucretia Estense Borgia Duchessa illustrissima di Ferrara,” and caused to be printed by Aldus Manutius, the leaflets which, under the title Gli Asolani, ne’ quali si ragiona d’ amore,[8] soon became a famous book in Italy.

The Virgin and Child in the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, popularly known as La Zingarella, which is accepted as the first in order of date among the works of this class, is still to a certain extent Bellinesque in the mode of conception and arrangement. Yet, in the depth, strength and richness of the colour-chord, in the atmospheric spaciousness and charm of the landscape background, in the breadth of the draperies, it is already Giorgionesque. Even Titian here asserts himself, and lays the foundation of his own manner. The characteristics of the divine Child differ widely from those adopted by Giorgione in the altarpieces of Castelfranco and the Prado Museum at Madrid. The Virgin is a woman beautified only by youth and the intensity of maternal love. Both Giorgione and Titian in their loveliest types of woman are sensuous compared with the Tuscans and Umbrians, or with such painters as Cavazzola of Verona and the suave Milanese, Bernardino Luini. But Giorgione’s sensuousness is that which may easily characterise the goddess, while Titian’s is that of the woman, much nearer to the everyday world in which both artists lived.

The famous Christ Carrying the Cross in the Chiesa di San Rocco in Venice was first ascribed by Vasari to Giorgione in his Life of the Castelfranco painter, then in the subsequent Life of Titian given to that master, but to a period very much too late in his career. The biographer quaintly adds: “This figure, which many have believed to be from the hand of Giorgione, is today the most revered object in Venice, and has received more charitable offerings in money than Titian and Giorgione together ever gained in the whole course of their life.” Indeed the embers of this debate remain hot to this day, as the Scuola di San Rocco now reattributes this work to the Castelfranco master, Giorgione. The picture, which presents “Christ dragged along by the executioner, with two spectators in the background,” resembles most among Giorgione’s authentic creations the Christ bearing the Cross. The resemblance is not, however, one of colour and technique, since this latter – one of the earliest Giorgiones – still recalls Giovanni Bellini, and perhaps even more strongly Cima; it is one of type and conception. In both renderings of the divine countenance there seems to be a sinister, disquieting look, almost a threat underlying that expression of serenity and humiliation accepted which is proper to the subject. Crowe and Cavalcaselle have called attention to a certain disproportion in the size of the head, as compared with that of the surrounding actors in the scene. A similar disproportion is to be observed in another early Titian, the Christ between Saint Andrew and Saint Catherine. Here the head of the infant Christ, who stands on a pedestal holding the Orb, between the two saints above mentioned, is strangely out of proportion to the rest. Crowe and Cavalcaselle refused to accept this picture as a genuine Titian (vol. ii. p. 432), but Morelli restored it to its rightful place among the early works.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Virgin and Child (“Gypsy Madonna”), c. 1510.

Oil on wood panel, 65.8 × 83.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Virgin and Child with Saint Catherine, Saint Dominic, and a Donor, c. 1512–1516.

Oil on canvas, 138 × 185 cm. Fondazione Magnani-Rocca, Parma.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Virgin and Child with Saints Dorothy and George, c. 1515.

Oil on wood, 86 × 130 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Next to these paintings, and certainly several years before the Three Ages and Sacred and Profane Love, one is inclined to place the Bishop of Paphos (Baffo) recommended by Alexander VI to Saint Peter, once in the collection of Charles I[9] and now in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. The main elements of Titian’s art may be seen here, in imperfect fusion, as in very few of his early productions. The somewhat undignified Saint Peter, enthroned on a kind of pedestal adorned with a high relief of classic design, of the type which we shall find again in the Sacred and Profane Love, recalls Giovanni Bellini, or rather his immediate followers. The magnificently robed Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia), wearing the triple tiara, echoes the portraiture style of Gentile Bellini and Carpaccio, while the kneeling Jacopo Pesaro – an ecclesiastic in tonsure and vesture, but none the less a commander of fleets, as the background suggests – is one of the most characteristic portraits of the Giorgionesque school. Its pathos and intensity contrast curiously with the less passionate absorption of the same Baffo in the renowned Retable of the Madonna of the Pesaro, painted twenty-three years later for the family chapel in the great Church of the Frari. It is the first in order of a great series, including the Ariosto of the National Gallery, the Man with a Glove, the Portrait of a Man in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, and perhaps the famous Concert in the Palazzo Pitti, once ascribed to Giorgione. Crowe, Cavalcaselle and Georges Lafenestre[10] have all called attention to the fact that the detested Borgia Pope died on the 18th of August 1503, and that the work cannot well have been executed after that time. It would have been a bold man who attempted to introduce the portrait of Alexander VI into a votive picture painted immediately after his death. How is it possible to assume that Sacred and Profane Love, one of the masterpieces of Venetian art, was painted one or two years earlier still, that is, in 1501 or at the latest in 1502? Let it be remembered that at that moment Giorgione himself had not fully developed the Giorgionesque. He had not painted his Castelfranco altarpiece, his Venus nor his Three Philosophers (Aeneas, Evander and Pallas). Old Gian Bellini himself had not entered upon that ultimate phase of his art which dates from the great San Zaccaria altarpiece finished in 1505.[11]

Vasari’s many manifest errors and disconcerting transpositions in the biography of Titian do not predispose us to give unlimited credence to his account of the strained relations between Giorgione and our painter, which are supposed to have arisen around the fresco decorations painted by the two artists on the façades of the new Fondaco de’ Tedeschi, erected to replace that burnt down on the 28th of January 1505. That they decorated it together with a series of frescos for which the exterior of the Fondaco is famous is all that is known for certain, Titian being apparently employed as the subordinate of his friend and master. Of these frescos only one figure, doubtfully assigned to Titian, and facing the Grand Canal, has been preserved in a much-damaged condition, the few fragments that remained of those facing the side canal having been destroyed in 1884.[12] Vasari shows us a Giorgione angry because he has been complimented by friends on the superior beauty of some work on the “facciata di verso la Merceria” which in reality belonged to Titian, thereupon implacably cutting short their connection and friendship. This version is confirmed by Dolce, but refuted by Tizianello’s Anonimo. There is one factor that makes it particularly difficult to make even a tentative chronological arrangement of Titian’s early works. This is that in the painted poesie of the earlier Venetian art of which the seeds are to be found in Giovanni Bellini and Cima, and the development of which is identified with Giorgione, Titian surrendered himself to the overmastering influence of the latter with less reservation of his own individuality than in his sacred works. In the earlier imaginative subjects the vivifying glow of Giorgionesque poetry moulds, colours, and expands the genius of Titian, but so naturally as neither to obliterate nor to constrain it. Indeed, even in Titian’s later period – checking an unveiled sensuousness which sometimes approaches dangerously near to a downright sensuality – the influence of the master and companion who vanished half a century before victoriously reasserts itself. It is this renewal of the Giorgionesque in the genius of the aged Titian that gives such an exquisite charm to the Venus of the Pardo, such a strange pathos to that still later Nymph and Shepherd.

The sacred works of the early period are Giorgionesque, too, but with a difference. Here from the very beginning there are to be noted a majestic placidity, a fullness of life, a splendour of representation, very different from the tremulous sweetness and spirit of aloofness and reserve which inform such creations as the Madonna of Castelfranco and the Madonna with Saint Francis and Saint Roch of the Prado Museum. Later, leaving ever farther behind the Giorgionesque ideal, we have the overpowering force and majesty of the Assunta, the true passion going hand-in-hand with the beauty of the Louvre’s Entombment, the rhetorical passion and scenic magnificence of the Saint Peter Martyr.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist and an Unidentified Saint, c. 1517–1520.

Oil on canvas, transferred from panel, 62.7 × 93 cm. National Gallery of Scotland (on loan from the collection of the Duke of Sutherland), Edinburgh.

Palma Vecchio (Giacomo or Jacopo Palma), The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1527–1528.

Oil on canvas, 127 × 195 cm. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.

The Baptism of Christ, with Zuanne Ram as donor, now in the Pinacoteca Capitolina in Rome, was attributed to Paris Bordone by Crowe and Cavalcaselle instead of to Titian, but the keen insight of Morelli led him to restore it authoritatively, and once for all, to the Venetian master. Internal evidence is indeed conclusive, as the picture must be assigned to a date when Bordone was but a child of tender years.[13] Here Titian is found treating this great scene in the life of Christ more in the style of a Giorgionesque pastoral than in the solemn hieratic fashion adopted by his great predecessors and contemporaries. The luxuriant landscape is in the main Giorgionesque, save that here and there a naked branch among the foliage – and on one of them the woodpecker – strongly recalls Giovanni Bellini. The same robust, round-limbed young Venetian, with the inexpressive face, does duty here as Saint John the Baptist, who in the Three Ages appears much more appropriately as the amorous shepherd. The image of Christ, here shown in the flower of youthful manhood, with luxuriant hair and softly curling beard, will mature later on into the divine Tribute Money. The question at once arises: Did Titian derive inspiration for this type of figure from Giovanni Bellini’s splendid Baptism of Christ? It was finished in 1510 for the Church of Santa Corona at Vicenza, but the younger artist might well have seen it a year or two previously, while it was in the course of execution in the workshop of the venerable master. Apart from its fresh naivety and rare pictorial charm, Titian’s conception appears trivial and merely anecdotal next to that of Bellini, so lofty, so consoling in its serene beauty, in the solemnity of its sunset colour![14] Only in the profile portrait of the donor, Zuanne Ram, placed awkwardly in the picture which is attractive in its naivety, but superbly painted, is Titian already a full-grown master standing alone.

The beautiful Virgin and Child with Saints Dorothy and George, placed in the Sala de la Reina Isabel of the Prado, is now officially restored to Titian, having been for years ascribed to Giorgione, whose style it echoes. It is in this piece especially that we meet with that element in the early art of the Cadorine which Crowe and Cavalcaselle defined as “Palmesque”. The Saint Dorothy and the Saint George are both types frequently to be met with in the works of the Bergamo painter, and it has been more than once remarked that the same beautiful model with hair of wavy gold must have sat for Giorgione, Titian and Palma. This can only be true, however, in a modified sense, seeing that Giorgione did not, so much as his contemporaries and followers, affect the type of the beautiful Venetian blond, “large, languishing, and lazy”. The hair of his women – both the sacred personages and the divinities nominally classical or wholly Venetian – is, as a rule, of a rich chestnut, or at the most dusky fair, and in them the Giorgionesque oval of the face tempers with its spirituality the strength of physical passion that the general physique denotes. The polished surface of this panel at Madrid, the execution, sound and finished without being finicky, and the high yellowish lights on the crimson draperie are all very characteristic of the first manner of Titian. The green hangings at the back of the picture are generally associated with the colour schemes of Palma. An old replica, with a slight variation in the image of the Child, is in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court, where it long bore – indeed it does so still on the frame – the name of Palma Vecchio.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Holy Family with a Shepherd, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas, 99.1 × 139.1 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Vasari assigns the exact date 1507 to the Tobias and the Angel now in the Galleria dell’Accademia, describing it with greater accuracy than he does any other work by Titian. He mentions even “the thicket, in which is Saint John the Baptist kneeling as he prays to heaven, whence comes a splendour of light”. The Aretine biographer is followed in this particular by Morelli, usually so eagle-eyed, so little bound by tradition in tracing the beginnings of a great painter. The gifted modern critic places the picture among the quite early works of our master. Notwithstanding this weight of authority, the writer feels bound to dissent from this view, and in this instance to follow Crowe and Cavalcaselle, who assign Tobias and the Angel to the a much later time in Titian’s long career. The picture, though it hangs high in the little church for which it was painted, will speak for itself to those who interrogate it without parti pris. Neither in the figures – the magnificently classical yet living archangel Raphael and the more naive and realistic Tobias – nor in the rich landscape with Saint John the Baptist praying is there anything left of the early Giorgionesque manner. In the sweeping breadth of the execution, the summarising power of the brush and the glow of the colour from within, we have so much evidence of a style in its fullest maturity. It would be safe, therefore, to place the picture well on in Titian’s middle period.[15]

The Three Ages in the National Gallery of Scotland and the Sacred and Profane Love in the Borghese Gallery represent the apogee of Titian’s Giorgionesque style. Glowing through and through with the spirit of the master-poet among Venetian painters, yet possibly falling short a little of that subtle charm of his, compounded indefinably of sensuous delight and spiritual yearning, these two masterpieces carry the Giorgionesque technically a pretty wide step farther than the inventor of the style took it. Barbarelli never absolutely threw off the trammels of the quattrocento, except in his portraits, but retained to the last – not as a drawback, but rather as an added charm – the naivety, the hardly perceptible hesitation proper to art not absolutely fully fledged.

Palma Vecchio (Giacomo or Jacopo Palma), The Holy Family with Mary Magdalene and the Infant Saint John the Baptist, c. 1520.

Oil on wood, 87 × 117 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Mary with Child and Four Saints (Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist, Saint Paul, Saint Mary Magdalene, and Saint Jerome), c. 1516–1520.

Oil on wood, 138 × 191 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Virgin and Child with Saint Stephen, Saint Jerome, and Saint Maurice, c. 1520.

Oil on canvas, H: 110 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Virgin and Child with a young John the Baptist and Saint Anthony the Abbot (“Madonna delle rose”), c. 1520–1523.

Oil on wood, 69 × 95 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

The Three Ages, from its analogies of type and manner with the Baptism in the Pinacoteca Capitolina, would appear to be the earlier of these two imaginative works, but in fact dates from later.[16] The tonality of the picture is of an exquisite silveriness; clear, moderate daylight, though this relative paleness may have been somewhat increased by time. It may be a little disconcerting at first sight for those who have known the lovely pastoral only from warm-toned, brown copies. It is still difficult to battle with the deeply-rooted notion that there can be no Giorgione, no painting of his school, without the accompaniment of rich brown tones. The shepherdess has a robe of fairest crimson, and her flower-crowned locks approach the blond cendré hue that distinguishes so many of Palma’s donne, as opposed to the ruddier gold that Titian himself generally affects. The more passionate of the two, she gazes straight into the eyes of her strong-limbed rustic lover, who half-reclining rests his hand upon her shoulder. On the twin reed pipes, which she still holds in her hands, she has just breathed forth a strain of music, and to it, as it still lingers in their ears, they yield themselves entranced. Here the youth is naked, the maid clothed and adorned – a reversal, this, of the Rustic Concert in the Louvre, traditionally attributed to Giorgione but now credited to Titian, where the women are undraped, and the amorous young cavaliers appear in complete and rich attire. To the right are a group of thoroughly Titianesque amorini; the winged one, dominating the others, being perhaps Amor himself, while in the distance an old man contemplates skulls ranged round him on the ground – obvious reminders of the last stage of all, at which he has so nearly arrived. There is here a wonderful unity between the even, unaccented harmony of the delicate tonality and the mood of the figures, each aiding the other to express the moment of pause in nature and in love, which in itself is a delight more deep than all that the very whirlwind of passion can give. Near at hand may be pitfalls, the smiling love-god may prove less innocent than he looks, and in the distance Fate may be foreshadowed by the figure of weary Age awaiting Death. Yet this one moment is all the lovers’ own, and they profane it not by speech, but stir their happy languor only with faint notes of music borne on the still, warm air.

The Sacred and Profane Love in the Borghese Gallery is one of the world’s greatest pictures, and without doubt the masterpiece of the early or Giorgionesque period. Today surely no one will contradict Morelli when he places it at the end of that period, which it so incomparably sums up. It could never have been created at the beginning, when its perfection would be as incomprehensible as the less absolute achievement displayed in other early pieces, which such a classification as this would place after the Borghese picture. The accompanying reproduction obviates all necessity for a detailed description. Afterwards Titian painted perhaps more wonderfully still, with a more sweeping vigour of brush, a higher authority, and so brilliant and diversified a play of light. He never attained a higher finish and perfection of its kind, or more admirably suited the technical means to the goal. He never so completely reflected the rays received from Giorgione, coloured with the splendour of his own genius, as he did here. The delicious sunset landscape has all the Giorgionesque elements, with more spaciousness, and lines of a still more suave harmony. The grand Venetian donna who sits sumptuously robed, flower-crowned and even gloved, at the sculptured classical fountain is the noblest in her loveliness, as she is one of the first in a long line of voluptuous beauties who will occupy the greatest brushes of the cinquecento. The little love-god who, insidiously intervening, paddles in the water of the fountain and troubles its surface, is Titian’s very own, owing nothing to any forerunner. The divinely beautiful Profane Love – or, as we shall presently see, Venus – is the most flawless presentment of female loveliness unveiled, save only the Venus of Giorgione himself in the Dresden Gallery. The radiant freshness of the face, with its glory of half-unbound hair, does not, indeed, equal the sovereign loveliness of the Dresden Venus or the disquieting charm of the Giovanelli Zingarella (properly Hypsipyle). Its beauty is all on the surface, while theirs stimulates the imagination of the beholder. The body with its strong, supple beauty, its unforced harmony of line and movement, with its golden glow of flesh, set off in the true Giorgionesque fashion by the warm white of the slender, diaphanous drapery, by the splendid crimson mantle with the changing hues and high light is, however, the most perfect poem of the human body that Titian ever achieved. Only in the late Venus of the Pardo, which so closely follows the chief motif of Giorgione’s Venus, does he approach it in frankness and purity. Far more genuinely classical is it in spirit, because more living and more solidly founded on natural truth, than anything that the Florentine or Roman schools, so much more assiduous in their study of classical antiquity, have brought forth.[17]

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Virgin with Child, Saint George, Saint Zachary, and the Infant Saint John, called “The Virgin with the Cherries”, c. 1516–1518.

Oil on wood transposed onto canvas, 81 × 99.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

It is impossible to discuss here in detail all the conjectural explanations which have been hazarded with regard to this most popular of all Venetian pictures – least of all that strange one brought forward by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, the Artless and Sated Love, for which they have found so little acceptance. But we may no longer wrap ourselves in an atmosphere of dreamy conjecture and show no more than languid desire to solve the fascinating problem. Taking as his starting-point the pictures described by Marcantonio Michiel (the Anonimo of Jacopo Morelli), in the house of Messer Taddeo Contarini of Venice, as the Inferno with Aeneas and Anchises and Landscape with the Birth of Paris, Franz Wickhoff[18] has proceeded, we have seen, to rename, with a daring crowned by a success nothing short of surprising, several of Barbarelli’s best known works. The Three Philosophers he calls Aeneas, Evander and Pallas, the Giovanelli Tempest with the Gypsy and the Soldier he explains anew as Admetus and Hypsipyle.[19] The subject known to us in an early plate of Marcantonio Raimondi, and popularly called, or rather miscalled, the Dream of Raphael, is recognised by Wickhoff as having its root in the art of Giorgione. He identifies the mysterious subject with one cited by Servius, the commentator on Virgil, who relates how, when two maidens were sleeping side by side in the Temple of the Penates at Lavinium (as he puts it), the unchaste one was killed by lightning, while the other remained in peaceful sleep.

Passing on to the Giorgionesque period of Titian, he boldly sets to work on the world-famous Sacred and Profane Love, and shows us the Cadorine painter interpreting, at the suggestion of some learned humanist at his elbow, an incident in the Seventh Book of the Argonautica of Valerius Flaccus – that wearisome imitation of the similarly named epic of Apollonius Rhodius. Medea – the sumptuously attired dame who does duty as Sacred Love – sits at the fountain in unrestful self-communing, leaning one arm on a mysterious casket, and holding in her right hand a bunch of wonder-working herbs. She will not yield to her new-born love for the Greek enemy Jason, because this love is the most shameful treason to father and people. But to her comes Venus in the form of the sorceress Circe, the sister of Medea’s father, irresistibly pleading that she must go to the alien lover, who waits in the wood. It is the vain resistance of Medea, hopelessly caught in the toils of love, powerless for all her enchantments to resist; it is the subtle persuasion of Venus, seemingly invisible – in Titian’s realisation of the legend – to the woman she tempts, that constitutes the main theme upon which Titian has built his masterpiece. Moritz Thausing[20] had already got half-way towards the unravelling of the true subject when he described the Borghese picture as The Maiden with Venus and Amor at the Well. The likelihood of Wickhoff’s brilliant interpretation becomes greater when we reflect that Titian at least twice afterwards borrowed subjects from classical Antiquity, taking his Offering to Venus, now at Madrid, from the Erotes of Philostratus, and the wonderful Bacchus and Ariadne at the National Gallery from the Epithalamium Pelei et Thetidos of Catullus.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Madonna di San Niccolò (San Niccolò Altarpiece), c. 1520–1525.

Oil on wood transposed onto canvas, 420 × 290 cm. Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City.

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), Madonna of Foligno, 1511–1512.

Oil tempera on wood transferred onto canvas, 308 × 198 cm. Musei Vaticani, Vatican City.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Assumption of the Virgin, 1516–1518.

Oil on panel, 690 × 360 cm. Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Retable of the Pesaro Family, or Retable of the Madonna of the Pesaro, 1519–1526.

Oil on canvas, 385 × 270 cm. Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice.

It is no use disguising the fact that, grateful as the true student of Italian art must be for such guidance as is here given, it comes to him at first as a shock that these mysterious creations of the ardent young poet-painters, in the presence of which we have most of us so willingly allowed reason and argument to stand in abeyance, should thus have hard, clear lines drawn, as it were, round their deliciously vague contours. It is their very vagueness and strangeness, the atmosphere of pause and quiet that they bring with them, the way in which they indefinably take possession of the beholder, body and soul, that above and beyond their radiant beauty have made them dear to successive generations. And yet we need not mourn overmuch, nor too painfully set to work to revise our whole conception of Venetian idyllic art as matured in the first years of the cinquecento. True, some humanist such as Pietro Bembo, no less amorous than learned and fastidious, must have found all these fine stories from Virgil, Catullus, Statius and the lesser luminaries of antique poetry for Titian and Giorgione, which luckily for the world they have interpreted in their own fashion. The humanists themselves would no doubt have preferred the more laborious and at the same time more fantastic Florentine fashion of giving plastic form in every particular to their elaborate symbolisms, their artificial conceits and their classical legends. But we may unfeignedly rejoice that the Venetian painters of the golden prime disdained to represent – or possibly unconsciously shrank from representing – the mere dramatic moment, the mere dramatic and historical character of a subject thus furnished to them. In such pictures as the Adrastus and Hypsipyle and Aeneas and Evander, Giorgione represents less that which has been related to him of those ancient legends so much as his own mood when he is brought into contact with them. He transposes his motif from a dramatic into a lyrical atmosphere, and gives it forth anew, transformed into something “rich and strange”, coloured for ever with his own inspired yet so warmly human fantasy. Titian, in Sacred and Profane Love, as for identification we must still continue to call it, strives to keep close to the main lines of his story, in this differing from Giorgione. But for all that, his love for the rich beauty of the Venetian country, for the splendour of female loveliness unveiled and for the piquant contrast of female loveliness clothed and sumptuously adorned, has conquered. He has presented the Romanised legend of the fair Colchian sorceress in such a delightfully misleading fashion that it has taken all these centuries to decipher its true import. What Giorgione and Titian have consciously or unconsciously achieved in these exquisite idylls is the indissoluble union of humanity with nature; outwardly quiescent, yet pulsating with an inner life and passion. It is nature herself that mysteriously responds in these painted poems, that interprets for the beholder the moods of man, much as a mighty orchestra – nature ordered and controlled. This is so that it may by its undercurrent explain to him who knows how to listen what the very personages of the drama may not proclaim aloud for themselves. And so we may be deeply grateful to Wickhoff for his interpretations, no less sound and thoroughly worked out than they are on a first acquaintance startling. And yet we need not for all that shatter our old ideals, nor force ourselves too persistently to look at Venetian art from another more prosaic, precise and literal standpoint.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Saint Mark with Saints Cosmas, Damian, Roch, and Sebastian, 1511.

Oil on wood panel, 230 × 119 cm. Santa Maria della Salute, Venice.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Virgin with Saint Francis, Saint Blaise, and the Donor Alvise Gozzi, called the Gozzi Retable, 1520.

Oil on wood panel, 312 × 215 cm. Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti, Ancona.

It has been pointed out by Titian’s biographers that the wars which followed the League of Cambrai had the effect of dispersing the chief Venetian artists of the younger generation all over northern Italy. It was not long after this – on the death of his master Giorgione – that Sebastiano del Piombo migrated to Rome and, so far as he could, shook off his allegiance to the new Venetian art. It was then that Titian temporarily left his adoptive city to do work in fresco at Padua and Vicenza. If the date 1508, given by Vasari for the great frieze-like wood engraving, The Triumph of Faith, is to be accepted, it must be held that it was executed before the journey to Padua. Ridolfi[21] cites painted compositions of the Triumph of Faith as either the originals or the repetitions of the wood engravings, for which Titian himself drew the blocks. The frescos themselves, if indeed Titian carried them out on the walls of his house at Padua, as has been suggested, have perished; but there does not appear to be any direct evidence that they ever came into existence. The types, though broadened and coarsened in the process of translation into wood engraving, are not materially at variance with those in the frescos of the Scuola del Santo. But the movement, the spirit of the whole, is essentially different. This mighty, onward-sweeping procession, with Adam and Eve, the Patriarchs, the Prophets and Sibyls, the martyred Innocents, the great chariot with Christ enthroned, drawn by the four Doctors of the Church and impelled forward by the Emblems of the four Evangelists, with a great company of Apostles and Martyrs following, has all the vigour and elasticity, all the decorative amplitude that is wanting in the frescos of the Scuola del Santo. It is obvious that inspiration was derived from the Triumphs of Mantegna, then already widely popularised by numerous engravings. Titian and those under whose inspiration he worked obviously intended an antithesis to the great series of canvases presenting the apotheosis of Julius Caesar, which were then to be seen in nearby Mantua. Have we here another pictorial commentary, like the famous Tribute Money, with which we shall have to deal presently, on the “Quod est Caesaris Caesari, quod est Dei Deo”, which was the favourite device of Alfonso of Ferrara and the legend round his gold coins? The whole question is interesting, and deserves more careful consideration than can be accorded to it on the present occasion. It was not until he reached extreme old age that such an impulse of sacred passion would again colour the art of the painter of Cadore as it did here. In the earlier period of his working life the Triumph of Faith constitutes a striking exception.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Daniel and Suzanne (Christ and the Adulterous Wife), 1508–1510.

Oil on canvas, 139.2 × 181.7 cm. Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Christ Carrying the Cross, c. 1506–1507.

Oil on canvas, 70 × 100 cm. Scuola del Santo, Venice.

Passing over, as relatively unimportant, Titian’s share in the much-defaced fresco decorations of the Scuola del Carmine, we come now to those more celebrated ones in the Scuola del Santo. Of the sixteen frescos executed in 1511 by Titian, in concert with Domenico Campagnola and other assistants of less fame, the following three are from the brush of the master himself: The Miracle of the Newborn Child, Saint Anthony Heals the Leg of a Youth and The Miracle of the jealous Husband. Here the figures, the composition and the beautiful landscape backgrounds bear unmistakably the trace of Giorgione’s influence. The composition has just the timidity and lack of rhythm and variety that to the last marks that of Barbarelli. The figures have his naive truth, his warmth and splendour of life, but not his gilding touch of spirituality to lift the uninspiring subjects a little above the actual. The Miracle of the jealous Husband is dramatic, almost terrible in its fierce, awkward realism, yet it does not rise much higher in interpretation than what our neighbours would today call the crime passionnel.

A convenient date for the magnificent Saint Mark with Saints Cosmas, Damian, Roch, and Sebastian is 1511, when Titian, having completed his share of the work at the Scuola del Santo, returned to Venice. True, it is still thoroughly Giorgionesque, except in the truculent Saint Mark; but so were the recently terminated frescos. The noble altarpiece[22] symbolises, or rather commemorates, the steadfastness of the State face to face with the terrors of the League of Cambrai. On one side are Saint Sebastian, standing, perhaps, for martyrdom by superior force of arms, and Saint Roch for plague (the plague of Venice in 1510); on the other, Saints Cosmas and Damian, suggesting the healing of these evils. The colour is Giorgionesque in that truer sense in which Barbarelli’s own could also be described. In particular it shows points of contact with the colouring of the Three Philosophers, which, on the authority of Marcantonio Michiel (the Anonimo), is rightly or wrongly held to be one of the last works of the Castelfranco master. That is to say, it is both sumptuous and boldly contrasting in hues, the sovereign unity of general tone not being attained by any sacrifice or attenuation, nor by any undue fusion of these, as in some of the second-rate Giorgionesques. Common to both is the use of a brilliant scarlet, which Giorgione successfully employs in the robe of the Trojan Aeneas, and Titian on a more extensive scale in that of one of the healing saints. These last are among the most admirable portrait-figures in Titian’s life work. In them a simplicity and concentration akin to that of Giovanni Bellini and Bartolommeo Montagna is combined with the suavity and flexibility of Barbarelli. The Saint Sebastian is the most beautiful among the youthful male figures, as the Venus of Giorgione and the Venus of the Sacred and Profane Love are the most beautiful among the female figures to be found in the Venetian art of a century in which such presentations of youth in its flower abounded. There is something androgynous, in the true sense of the word, in the union of the strength and pride of lusty youth with a grace which is almost feminine in its suavity, yet not offensively effeminate. It should be noted that a delight in portraying the fresh comeliness and elastic beauty of form proper to a youth on the point of becoming a man was common to many Venetian painters at this stage, and coloured their art as it had coloured the whole art of Greece.

The singularly attractive, yet a little puzzling, Holy Family with a Shepherd, is in the National Gallery. The landscape is of the early type, and the execution is, even for that time, curiously small and lacking in breadth. In particular the projecting rock, with its fringe of half-bare shrubs profiled against the sky, recalls the backgrounds of the Scuola del Santo frescos. The noble type and the stilted attitude of the Saint Joseph suggest the Saint Mark of the Salute. The frank note of bright scarlet in the jacket of the thick-set young shepherd, who recalls Palma more than the idyllic charm of Giorgione, is to be found again in the Salute picture. The unusually pensive Madonna reminds the spectator, with a certain fleshiness and matronly amplitude of proportion, though by no means in sentiment, of the sumptuous dames who look on so unconcernedly in the Miracle of the Newborn Child of the Scuola. Her draperies show, too, the jagged breaks and close parallel folds of the early time before complete freedom of design was attained.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Tribute-Money, c. 1516.

Oil on wood, 75 × 56 cm. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Baptism of Christ, c. 1513–1514.

Oil on wood, 115 × 89 cm. Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Noli me tangere, c. 1514.

Oil on canvas, 110.5 × 91.9 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Entombment, c. 1520.

Oil on canvas, 148 × 212 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

The splendidly beautiful Salome with the Head of John the Baptist in the Doria Gallery, formerly attributed to Pordenone, but definitively placed by Morelli among the Giorgionesque works of Titian, belongs to about the same period as Sacred and Profane Love, and would therefore come in before rather than after the sojourn at Padua and Vicenza. The intention was not so much to emphasise the tragic character of the motif as to exhibit to the highest advantage the voluptuous charm, the languid indifference of a Venetian beauty posing for Herod’s baleful consort. Repetitions of this Salome existed in the Northbrook Collection and in that of R. H. Benson. A work traceable back to Giorgione would appear to underlie, not only this Doria picture, but that Salome which at Dorchester House is attributed to Pordenone, and another similar one by Palma Vecchio, of which a late copy exists in the collection of the Earl of Chichester. The common origin of these works is noticeable in the head of Saint John on the charger, as it appears in each. All of them again show a family resemblance in this particular respect to the interesting full-length Judith at the Hermitage, now ascribed to Giorgione, as well as to the over-painted half-length Judith in the Querini-Stampalia Collection at Venice, and to Hollar’s print after a picture supposed by the engraver to give the portrait of Giorgione himself in the character of David, the slayer of Goliath.[23] The sumptuous but much-injured Vanitas, which is in the Alte Pinakothek of Munich – a beautiful woman of the same opulent type as the Salome, holding a mirror which reflects jewels and other symbols of earthly vanity – may be classed with the last-named work. Again we owe it to Morelli[24] that this painting, ascribed by Crowe and Cavalcaselle – as the Salome was ascribed – to Pordenone, has been with general acceptance classed among the early works of Titian. The popular Flora of the Uffizi, a beautiful thing still, though much of the bloom of its beauty has been effaced, must be placed rather later in this section of Titian’s life-work, displaying as it does a technique more facile and accomplished, and a conception of a somewhat higher individuality. The model is surely the same as that which has served for the Venus of Sacred and Profane Love, though the picture comes some years after that piece. Later still comes the so-called Alfonso d’Este and Laura Dianti, known as the Young Woman with a Mirror in the Louvre. Another puzzle is provided by the beautiful Noli me tangere of the National Gallery, which must have its place somewhere here among the early works. The picture is still Giorgionesque, most markedly so in the character of the beautiful landscape; yet the execution shows an altogether unusual freedom and mastery for that period. The Magdalene is, appropriately enough, of the same type as the exquisite, golden blond courtesans – or, if you will, models – who constantly appear and reappear in this period of Venetian art. Hardly anywhere has the painter exhibited a more wonderful freedom and subtlety of brush than in the figure of the Christ, in which glowing flesh is so finely set off by the white of fluttering, half-transparent draperies. The canvas has exquisite colour, almost without colours; the only tint of any very defined character being the dark red of the Magdalene’s robe. Yet a certain affectation, a certain exaggeration of fluttering movement and strained attitude repel the beholder a little at first, and neutralise for him the rare beauties of the canvas. It is as if a wave of some strange transient influence passed over Titian at this moment, then to be dissipated.

But to turn now once more to the series of our master’s Holy Families and Sacred Conversations which began with La Zingarella, and was continued with the Virgin and Child with Saints Dorothy and George of Madrid. The most popular of all those belonging to this early period is the Virgin with the Cherries in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Here the painter is already completely himself. He will go much farther in breadth if not in polish, in transparency, in forcefulness, if not in attractiveness of colour; but he is now, in sacred art at any rate, practically free from outside influences. From the pensive girl-Madonna of Giorgione we now have the radiant young matron of Titian, joyous yet calm in her play with the infant Christ, while the Madonna of his master and friend was unrestful and full of tender foreboding even in seeming repose. Pretty close behind this must have followed the Virgin and Child with Saint Stephen, Saint Jerome and Saint Maurice in the Louvre, in which the rich harmonies of colour strike a somewhat deeper note. An atelier repetition of this fine original is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum; the only material variation traceable in this last-named example being that in lieu of Saint Ambrose, wearing a kind of biretta, we have Saint Jerome bareheaded.

Very near in time and style to this particular series, with which it may safely be grouped, is the beautiful and finely preserved Holy Family, erroneously attributed to Palma Vecchio. Deep glowing richness of colour and smooth perfection without slightness of finish make this picture remarkable, notwithstanding its lack of any deeper significance. Nor must there be forgotten in an enumeration of the early Holy Families, one of the loveliest of all, the Virgin and Child with a Young Saint John the Baptist and Saint Anthony the Abbot, which adorns the Venetian section of the Uffizi Gallery. Here the relationship with Giorgione is more clearly shown than in any of these Holy Families of the first period, and in so far as the painting, which cannot be placed very early among them, constitutes a partial exception in the series. The Virgin is of a more refined and pensive type than in the Virgin and Child with Saint Stephen, Saint Jerome and Saint Maurice in the Louvre, and the divine Child less robust in build and aspect. The magnificent Saint Anthony is quite Giorgionesque in the serenity tinged with sadness of his contemplative mood.

Last of all in this particular group – another work in respect of which Morelli has played the rescuer – is the Mary and Child with Four Saints in the Dresden Gallery. This is a much-injured but eminently Titianesque work, which may be said to bring this particular series to within a couple of years or so of the Assunta, that great landmark of the first period of maturity. The type of the Madonna here is still very similar to that in the Virgin with the Cherries.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Polyptych of the Resurrection (Polyptych Averoldi), 1520–1522.

Oil on wood panel, centre panel: 278 × 122 cm; upper side panels each: 79 × 65 cm; lower side panels each: 170 × 65 cm. Santi Nazaro e Celso, Brescia.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Tobias and the Angel, c. 1512.

Oil on wood, 170 × 146 cm. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.

Apart from all these sacred works, and in every respect an exceptional production, is the world-famous Tribute-Money of the Dresden Gallery. The date of this presumed early work of Titian is problematic. For once agreeing with Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Morelli is inclined to disregard the testimony of Vasari, from whose text we might infer that it was painted in or after the year 1514, and to place it as far back as 1508. Notwithstanding this weight of authority, the writer is strongly inclined, following Vasari in this instance, and trusting to certain indications furnished by the picture itself, to return to the date 1514 or thereabouts. There is no valid reason to doubt that The Tribute-Money was painted for Alfonso I of Ferrara, seeing that it so aptly illustrates the already quoted legend on his coins: Quod est Caesaris Caesari, quod est Dei Deo. According to Vasari, it was painted nella porta d’un armario – that is to say, in the door of a press or wardrobe. But this statement need not be taken in its most literal sense. If it were to be assumed from this passage that the picture was painted on the spot, its date must be advanced to 1516, since Titian did not pay his first visit to Ferrara before that year. There are no sufficient grounds, however, for assuming that he did not execute his wonderful panel in the usual fashion – that is to say, at home in Venice. The last finishing touches might, perhaps, have been given to it in situ, as they were to Bellini’s Bacchanal, also done for the Duke of Ferrara. The extraordinary finish of the painting, which is hardly to be paralleled in the life work of the artist, may have been due to his desire to “show his hand” to his new patron in a subject which touched him so closely. And then the finish is not of the quattrocento type, not such as we find, for instance, in the Leonardo Loredano of Giovanni Bellini, the finest panels of Cima, or the early Christ bearing the Cross of Giorgione. In it the exquisite polish of surface and consummate rendering of detail are combined with the utmost breadth and majesty of composition, with a now perfect freedom in the casting of the draperies. It is difficult, indeed, to imagine that this masterpiece – so eminently a work of the cinquecento and one, too, in which the master of Cadore rose superior to all influences, even to that of Giorgione – could have been painted in 1508. That would be some two years before Bellini’s Baptism of Christ in Santa Corona, and in all probability before the Three Philosophers of Giorgione himself. It appears to have most in common with Titian’s own early picture Saint Mark of the Salute – not so much in technique, indeed, as in general style – though it is very much less Giorgionesque. To praise the Tribute Money anew after it has been so incomparably well praised seems almost an impertinence. The soft radiance of the colour matches so well the tempered majesty, the infinite gentleness of the conception; the spirituality, which is of the essence of the august subject, is so happily expressed, without any sensible diminution of the splendour of Renaissance art approaching its highest point. And yet nothing could be simpler than the scheme of colour as compared with the complex harmonies which Venetian art in a somewhat later phase affected. Frank contrasts are established between the tender, glowing flesh of the Christ, seen in all the glory of manhood, and the coarse, brown skin of the son of the people who appears as the Pharisee; between the bright yet tempered red of Christ’s robe and the deep blue of his mantle. But the golden glow, which is Titian’s own, envelops the contrasting figures and the contrasting hues in its harmonising atmosphere, and gives unity to the whole.[25]

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Miracle of the Jealous Husband, 1511.

Fresco, 340 × 185 cm. Scuola del Santo, Padua.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Saint Anthony heals the Leg of a Youth, 1511.

Fresco, 340 × 207 cm. Scuola del Santo, Padua.

A small group of early portraits – all of them somewhat difficult to place – call for attention before we proceed. Probably the earliest portrait among those as yet recognised as from the hand of our painter – leaving out of the question the Baffo and the portrait-figures in the great Saint Mark of the Salute – is the magnificent Ariosto (also known as The Man with the Quilted Sleeve) in the National Gallery of London. There is very considerable doubt, to say the least, as to whether this half-length really represents the court poet of Ferrara, but the point requires more elaborate discussion than can be here conceded to it. The soberly tinted yet sumptuous picture is thoroughly Giorgionesque in its general arrangement and general tone, and in this respect it is the fitting companion and the descendant of Giorgione’s Antonio Broccardo at Budapest and his Knight of Malta at the Uffizi. Its resemblance to the celebrated Sciarra Violin-Player by Sebastiano del Piombo, often ascribed to Raphael, is very striking, particularly regarding the general lines of the composition.[26] The handsome, manly head has lost both subtlety and character through some too severe cleaning process, but Venetian art has hardly anything more magnificent to show than the costume, with the quilted sleeve of steely, blue-grey satin which occupies so prominent a place in the picture.

The Concert of the Palazzo Pitti, which depicts a young Augustinian monk playing on a keyed instrument, on one side of him a youthful cavalier in a plumed hat, on the other a bareheaded clerk holding a bass viol, was, until Morelli, almost universally looked upon as one of the most typical Giorgiones.[27] The most gifted of the purely aesthetic critics who have approached the Italian Renaissance, Walter Pater, actually built round this Concert his exquisite study on the School of Giorgione. There can be little doubt, however, that Morelli was right in denying the authorship of Barbarelli, and tentatively assigning the subtly attractive and tender Concert to Titian’s early period. To express a definitive opinion on the latter point in the present state of the picture would be somewhat hazardous. The portrait of the modish young cavalier and that of the staid elderly clerk, whose baldness renders tonsure impossible – that is just those portions of the canvas which are least well preserved – are also those that least conclusively suggest our master. The passion-worn, ultra-sensitive physiognomy of the young Augustinian is, undoubtedly, in its very essence a Giorgionesque creation, for the fellows of which we must turn to the Castelfranco master’s Antonio Broccardo, to his male portraits in Berlin and at the Uffizi, and to his figure of the youthful Pallas, son of Evander, in the Three Philosophers. Closer to it, all the same, are the Raffo and the two portraits in the Saint Mark of the Salute, and closer still is the supremely fine Man with a Glove of the Salon Carré, that later production of Vecelli’s early period. The Concert of the Palazzo Pitti displays an art certainly not finer or more delicate, but yet in its technical processes broader, swifter, and more synthetic than anything that we can with certainty point to in the life work of Barbarelli. The large but handsome and flexible hands of the player are much nearer in type and treatment to Titian than they are to his master. The beautiful motif – music for one happy moment uniting by invisible bonds of sympathy three human beings – is akin to that in the Three Ages, though there love steps in as the beautifier of rustic harmony. It is to be found also in Titian’s Rustic Concert in the Louvre, in which the thrumming of the lute is one among many delights appealing to the senses. This smouldering heat, this tragic passion in which youth revels, looking back already with discontent, yet forward also with unquenchable yearning, is the keynote of the Giorgionesque and the early Titianesque male portraiture. Altogether apart, and less due to a reaction from physical ardour, is the exquisite sensitivity of Lorenzo Lotto, who sees most willingly in his sitters those qualities that are in the closest sympathy with his own highly-strung nature, and loves to present them as some secret, indefinable woe tears at their heart-strings. A strong element of the Giorgionesque pathos informs still and gives charm to the Sciarra Violin-Player of Sebastiano del Piombo; only there it is already tempered by the haughty self-restraint more proper to Florentine and Roman portraiture. There is little or nothing to add after this as to the Man with a Glove, except that as a representation of aristocratic youth it has hardly a parallel among the master’s works except, perhaps, a later and equally admirable, though less distinguished, portrait in the Palazzo Pitti.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу

3

For these and other particulars of the childhood of Titian, see Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s elaborate Life and Times of Titian (second edition, 1881), in which are carefully summarised all the general and local authorities on the subject.

4

Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times of Titian, vol. I. p. 29.

5

Die Galerien zu München und Dresden, p. 75.

6

Carlo Ridolfi (better known as a historian of the Venetian school of art than as a Venetian painter of the late time) expressly states that Palma came to Venice young and learnt much from Titan: “C’ egli apprese certa dolcezza di colorire che si avvicina alle opere prime dello stesso Tiziano” (Lermolieff: Die Galerien zu München und Dresden).

7

Vasari, Le Vite: Giorgione da Castelfranco.

8

One of these is a description of wedding festivities presided over by the Queen at Asolo, to which came, among many other guests from the capital by the Lagunes, three Venetian gentlemen and three ladies. This gentle company, in a series of conversations, dwell upon, and embroider in many variations, that inexhaustible theme, the love of man for woman. A subject this which, transposed into an atmosphere at once more frankly sensuous and of a higher spirituality, might well have served as the basis for such a picture as Titian’s Rustic Concert in the Salon Carré of the Louvre!

9

Mentioned in one of the inventories of the king’s effects, taken after his execution, as Pope Alexander and Seignior Burgeo (Borgia) his son.

10

La Vie et l’Oeuvre du Titien, 1887.

11

The inscription on a cartellino at the base of the picture, Ritratto di uno di Casa Pesaro in Venetia che fu fatto generale di Sta chiesa. Titiano fecit, is unquestionably of much later date than the work itself. The cartellino is entirely out of perspective with the marble floor to which it is supposed to adhere. The part of the background showing the galleys of Pesaro’s fleet is so coarsely repainted that the original touch cannot be distinguished. The form “Titiano” is not to be found in any authentic picture by Vecelli. “Ticianus”, and much more rarely “Tician”, are the forms for the earlier period; “Titianus” is, as a rule, that of the later period. The two forms overlap in certain instances to be presently mentioned.

12

Kugler’s Italian Schools of Painting, re-edited by Sir Henry Layard.

13

Marcantonio Michiel, who saw this Baptism in the year 1531 in the house of Zuanne Ram at San Stefano in Venice, thus describes it: “La tavola del S. Zuane che battezza Cristo nel Giordano, che è nel fiume insino alle ginocchia, con el bel paese, ed esso M. Zuanne Ram ritratto sino al cinto, e con la schena contro li spettatori, fu de man de Tiziano” (Notizia d’ Opere di Disegno, pubblicata da J. Jacopo Morelli, Ed. Frizzoni, 1884).

14

This picture having been brought to completion in 1510, and Cima’s great altarpiece with the same subject, behind the high altar in the Church of San Giovanni in Bragora at Venice, being dated 1494, the inference is irresistible that in this case the head of the school borrowed much and without disguise from the painter who has always been looked upon as one of his close followers. In size, in distribution, in the arrangement and characterisation of the chief groups, the two altarpieces are so nearly related that the idea of a merely accidental and family resemblance must be dismissed. This type of Christ, then, of a perfect, manly beauty, of a divine meekness tempering majesty, dates back, not to Gian Bellini, but to Cima. The preferred type of the elder master is more passionate, more human. The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Cima in the National Gallery, shows, in a much more perfunctory fashion, a Christ similarly conceived; and the beautiful Man of Sorrows in the same collection, still nominally ascribed to Giovanni Bellini, if not from Cima’s own hand, is at any rate from that of an artist dominated by his influence. When the life’s work of the Conegliano master has been more closely studied in connection with that of his contemporaries, it will probably appear that he owes very much less to Bellini than it has been the fashion to assume. The idea of an actual subordinate co-operation with the caposcuola, like that of Bissolo, Rondinelli, Basaiti, and so many others, must be excluded. The earlier and more masculine work of Cima bears a definite relation to that of Bartolommeo Montagna.

15

Tobias and the Angel shows some curious points of contact with the large Madonna and Child with Saint Agnes and Saint John by Titian in the Louvre – a work which is far from equalling the San Marciliano picture throughout in quality. The beautiful head of the Saint Agnes is but that of the majestic archangel in reverse; the Saint John, though much younger than the Tobias, has very much the same type and movement of the head. There is in the Church of Santa Caterina in Venice a kind of paraphrase with many variations of the San Marciliano Titian, assigned by Ridolfi to the great master himself, but by Boschini to Santo Zago (Crowe and Cavalcaselle, vol. II. p. 432). Here the adapter has ruined Titian’s great conception by substituting his own trivial archangel for the superb figure of the original (see also a modern copy of this last piece in the Schack Gallery at Munich). A reproduction of the Titian has for purposes of comparison been placed at the end of the present monograph (p. 99).

16

Vasari places the Three Ages after the first visit to Ferrara, that is almost as much too late as he places the Tobias of the Galleria dell’Academia too early. He describes its subject as “un pastore ignudo ed una forese chi li porge certi flauti per che suoni.”

17

From an often-cited passage in the Anonimo, describing Giorgione’s great Venus now in the Dresden Gallery, in the year 1525, when it was in the house of Jeronimo Marcello at Venice, we learn that it was finished by Titian. The text says: “La tela della Venere nuda, che dorme ni uno paese con Cupidine, fu de mano de Zorzo da Castelfranco; ma lo paese e Cupidine furono finiti da Tiziano.” The Cupid, irretrievably damaged, has been altogether removed, but the landscape remains, and it certainly shows a strong family resemblance to those which enframe the figures in the Three Ages, Sacred and Profane Love, and the “Noli me tangere” of the National Gallery. The same Anonimo in 1530 saw in the house of Gabriel Vendramin at Venice a Dead Christ supported by an Angel, from the hand of Giorgone, which, according to him, had been retouched by Titian. It need hardly be pointed out, at this stage, that the work thus indicated has nothing in common with the coarse and thoroughly second-rate Dead Christ supported by Child-Angels, still to be seen at the Monte di Pietà of Treviso. The engraving of a Dead Christ supported by an Angel, reproduced in Lafenestre’s Vie et Œuvre du Titien as having possibly been derived from Giorgione’s original, is about as unlike his work or that of Titian as anything in sixteenth-century Italian art could possibly be. In the extravagance of its mannerism it comes much nearer to the late style of Pordenone or to that of his imitators.

18

Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen, Heft I. 1895.

19

See also as to these paintings by Giorgione, the Notizia d’ Opere di Disegno, pubblicata da D. Jacopo Morelli, Edizione Frizzoni, 1884.

20

M. Thausing, Wiener Kunstbriefe, 1884.

21

Le Meraviglie dell’ Arte.

22

One of the many inaccuracies of Vasari in his biography of Titian is to speak of the Saint Mark as “una piccola tavoletta, un S. Marco a sedere in mezzo a certi santi.”

23