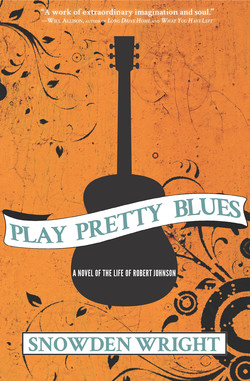

Читать книгу Play Pretty Blues - Snowden Wright - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление“Honeymoon Blues”

The first time Robert Johnson died he wasn’t Robert Johnson. On a dog day in the summer of 1928, as then heard by two of us and as later verified in newsprint by all six of us, a man fitting his description walked into the Sparks Farm Cotton Gin five minutes before it was demolished by dynamite. The man who walked in the front door was called Robert Spencer. The man who snuck out the back door named himself Robert Johnson.

We have spent the past seventy years searching for him. Time and again, he has evaded our pursuit. Time and again, he has given us but sight of his ghost. We have questioned locals and stapled signs to phone poles. We have thumbed through classifieds and whittled cryptic on bathroom walls. We have dry-rubbed headstones, placed wires statewide, and notified the sheriff. We have caught glimmer of his coattails, found footprints in red mud, and heard his laugh peal from a passing sedan. We have convinced ourselves he’ll send word. We have lied to his children. His name may not be the same to all of us—Mary Sue called him Caruthers, Betty called him Ledbetter—but to all of us he was husband.

Although they are by no means exhaustive, our records indicate that he was born the tenth child in a family known as Dodds, that he would eventually assume twelve separate aliases, that he officially died at least eight different times. The deaths were as fierce as his talent. In 1932, he was found straddling the bowl in an Arkansas white man’s outhouse, his face dismantled by the business end of a twelve-gauge. In 1929, somewhere between Memphis and Olive Branch, he turned a stolen Model T the wrong way on a one-way street. In 1936, he was discovered on the tracks behind a railway juke joint, his head set free of its soulless coil by a Louisiana-bound locomotive. Between 1933 and 1935, he was thrice buried in graves whose stones bore only two chiseled lines, one intersecting the other, that many believe symbolized our heavenly father’s time on the cross but that we maintain, even to this day, stood for the Roman numeral representing the place our children’s father held in the lineage of his family. His guitar, as he explained to each of us in post-coital sheets, bore that very mark for that very reason. “Momma sees it from above,” he said, sweat dripping on the strings. “I know it in my fingertips.”

The last time he died would last a lifetime. It would linger seventy years beyond the date, August 13, 1938, the evening of which he played at a country dance near Greenwood, Mississippi. It would echo in the shucked chambers of our chests as we lived through wars abroad and at home, through bondage, oppression, and freedom, through poverty and wealth of kith and kin. That at the time of his death he was less than thirty miles from each of our homes, that he mentioned to more than one passerby he meant to “return to his true family,” would perpetuate forever our questions that will go, as we now suspect, forever unanswered. Did he love us? we ask ourselves to this day. Did we love him?

All we can truly know is how we felt upon hearing the details of his final performance on this earth. At the country dance outside Greenwood, Robert Johnson, husband, father, legend, stood on a sawdust-covered stage, located the most attractive woman in the audience, and played his songs in her direction; he sang lyrics drenched with innuendo and made eye contact that could blind the weak, all methods we know first-hand. The explanation of his death confirmed most often by townsfolk from that evening involves the husband of the woman at whom he aimed his blues seduction. The husband sought vengeance by lacing the suspect bluesman’s whiskey with strychnine.

We knew the exact moment the poison entered his bloodstream. Helena wrung her tablecloths bloody. Mary Sue dreamt twisted visions of God’s wrath. Claudette spiced her cornbread with tears. Betty shook the cradle with her wails. Each of us saw the same vision of our husband crawling on the ground, hands and knees minced to ribbons by gravel, bottle tops, and cockleburs. Each of us watched in our minds as the toxin seeped into our husband’s brain, causing him to howl and to froth like a dog gone rabid. His limbs contorted in all the wrong ways. His eyes searched heavenward though his face looked elsewhere. At last, somewhere in a cotton field on a sleepy Delta dawn, Robert Johnson collapsed to the ground, dead.

Each of us lived at least half a day from the fateful scene. On the night of his murder, according to the stories that reached us by week’s end, a handful of drunks managed to form a search party, but their determination proved inversely proportional to their sobriety. They dropped their torches at first light. They called it a day on principle. Most of them left in pursuit of more whiskey, while the rest returned to their homes and families. Somewhere in a cotton field outside Greenwood, Mississippi, the body of our husband lay rotting beneath the highest stalks in county history. It was never found.

We will forever ponder his accidental grave. Did the hounds not track his scent because they smelled one of their own? Is there such thing as sacred ground for a man without a soul? Did his dark skin blend into the pitch of Precambrian floodplain?

Nary a public bulletin heralded the death of the musician who would one day be called the greatest blues singer of all time. The papers issued not a single proclamation. The wireless broadcast not a single eulogium. They should have waxed sensational on his genius in the newborn art; they should have poeticized his mastery of truss rod and fret board; they should have decreed music’s end come nigh. In the weeks following his death, none of those who attended Robert Johnson’s last performance reported the incident to the media or to authorities. The perpetrator of the crime, whose guilt we still deem beyond doubt, was never sentenced to his rightful acreage in Parchman Farm. We were deprived the sweet clink of shackle and chain, the lovely still-life of his face behind bars, the elegiac spectacle of his incarceration. Only time would avenge our husband’s murder.

Since his death our lives have been guided not merely by our search for the truth but also by our desire for retribution. We have lived in the shadow of a ghost. In the first few years after his demise, some of us migrated north to St. Louis and Chicago, some of us west to Texas and Oklahoma, all in trace of the path taken by his posthumous musical influence. Claudette collected a dossier of evidence of his life and death, including fingerprints, oral accounts, facial sketches, Mason jars of sampled soil, photographs and lithographs and phonographs, vials, beakers, bottles, locks of hair hermetically sealed in Tupperware and Glad-Lock. Mary Sue, the oldest of us, seduced every headliner she heard cover a Robert Johnson song. Tabitha, the youngest, spent years harassing his murderer’s family with coins glued to their porch’s floorboards, caps twisted loose on their salt shakers, and staples removed from their Swingline. Betty sought solace in the bottle. Helena, who never forgave herself for not bearing our mutual husband an heir, eventually married a writer of crossword puzzles and gave birth to three boys named various anagrams of “Robert Johnson.”

Even though we firmly believed in his death, our lives were plagued by the possibility he may still be among us. We raided whorehouses and drug dens in the hope we might find him astride a jaybird harlot. We saw eidetic echoes of his face in our compacts. We tore the feathered phone numbers from flyers for guitar lessons, staked-out record companies, deciphered liner notes, and showed up for open-call auditions, always expecting to find him as the sinister mastermind behind the music. We berated look-a-likes on the street, yanking on their hair that had to be a wig, tugging at their noses that had to be prosthetic. We opened our mailboxes looking for postcards from some Pacific archipelago or letters with lines blacked-out by some bureaucratic censor.

Only after we had given up hope of his return, only after we allowed ourselves to believe he was dead and would remain so forever, was Robert Johnson finally resurrected by music critics, record executives, and sales charts. It all began in 1961. Rock and roll musicians discovered his newly released LPs and scrutinized his techniques on the Gibson. Historians researched his life and investigated his death. Reporters held the public rapt with the story of his bargain at the crossroads. Decades after his death, our husband was famous to all the world, and we wept with both joy and sorrow. No longer were we the sole bearers of his memory. No longer was he ours and ours alone.