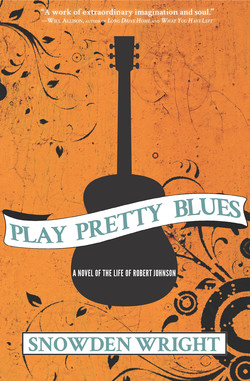

Читать книгу Play Pretty Blues - Snowden Wright - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

Over breakfast Leroy Spencer told his younger brother the gift would have to wait ’til after lunch. It was our husband’s twelfth birthday. At the kitchen table in the split-level tenement on Handwerker Hill’s south side, Robert upheld the appeal to his brother for some kind of hint concerning his birthday present. He asked Leroy, “Is it bigger than a breadbox?”

“Won’t tell.”

“Animal, vegetable, or mineral?”

“You got the wax in your ears again?” Leroy balled his napkin and lobbed it at his brother. “I said I’m not saying. Don’t ask again.”

“Is it in this room?”

Since his introduction to the household seven years back, over which time his mother yet seldom sent word, Robert had been so ignored by his father that the only person who gave him any mind was the oldest of his five sisters and six brothers. Leroy was twenty-seven. He worked days as a millwright at the Sperry Lumber Yard in Germantown and nights as a handyman at the Peabody Hotel on Union Avenue. He could clean the breech of a double barrel with a corncob and he could speak two languages of the Five Civilized Tribes and he could whistle any melody after a first listen. He kept in his closet a pinstripe suit cut slim of fine-grade tropical wool. He had a steady girlfriend most of the time, never drank but a drop, never partook of tobacco, and went to the early service on special occasions. Robert idolized him.

“Got some things need getting done,” Leroy said from his seat at the gateleg table, sopping his plate with cornbread. “You promise to behave, you get your present.”

“Cross my heart. Hope to die.”

“I’ll be back in a few hours.” Leroy walked to the single-bowl scullery sink, lathered his plate, paused at the ledge-and-brace threshold door, settled his hat, and turned the brass knob clockwise by half. “Don’t go running all over town while I’m gone.”

During those early years of his childhood, Robert Johnson, future guitarist, future singer, future lyricist, had known the world of Memphis to be a world at harmony with itself. Teams of horses would clip-clop their heavy hooves down Cotton Row, pulling wagons teeming with the season’s crop. Robert heard them. Merchants would sell their wares, newly improved hand tools and gimcrack beauty products and miraculously curative medicines, with the refrain of “Come and get, folks, come and get.” Robert heard them. On Sundays, the scratch choir at First Methodist Church in the Pinch District would sing the gospel by way of psalms, spirituals, and hymns from the Good Book. Robert heard them. On Fridays, the crowds at the local dog track, half a month’s pay on the line, would cheer their hardscrabble picks. Robert heard them. On Mondays, the lunch counter at Smith’s Rexall Drugs across from the courthouse would brim with tales of famous lawmen dead and promoted to Glory. Robert heard them. The blow of a horn from paddleboats, barges, and flatkeels would echo against the craggy bluffs of the Mississippi, and the whistle of a steam gong would signal the workday at the city’s paper mills, cotton gins, and dairy plants. Robert heard them. The distant susurrus of metal on metal would fill the rich air of Shelby County as Pullman cars stole their way inch by inch across the Harahan Bridge. Robert heard them. In the mornings, he heard thousands of crickets wail their vibrato from the thick leaves of chinaberry clusters. At noon, he heard wind chimes made of bent forks and old knives peal a clarion call from the flower gardens of Elmwood Cemetery. In the evenings, he heard hundreds of locusts scream their falsetto from the brittle branches of sycamore stands. At midnight, he heard the report of Derringers, Colts, and Winchesters burst chaotic from the dark alleys of Beale Street. Everywhere he heard stones in his passway. Everywhere he heard hellhounds on his trail. Everywhere he heard the crossroads at night.

On his twelfth birthday, thanks to the vow of a present, Robert Johnson chose to spend the hot morning hours practicing his chords in the backyard rather than exploring the various neighborhoods of Memphis. His undershirt stuck to his skin and his hands got soggy in the palm as he put the house behind him and strode across the yard. Summer had come early. Although the outdoor thermometer given gratis by the Chero-Cola distributor often reached the vicinity of triple digits—“Cool Yourself Down,” it read, “With a Glass of Royal Crown” —the broad canopy of a live oak strung with a Dunlop whitewall provided the backyard generous cover from the noontime sun. Robert laced the long, slender digits of his young hands and waited for a good, loud crack from each knuckle. He knelt at the base of the live oak, bit the inside of his cheek, and went to work on the diddley bow.

Our mutual husband told each of us about the construction of diddley bows during our respective courtships. He said to Mary Sue, “You hammer four or six nails into the trunk of a tree,” counting on her fingertips. He said to Betty, “You run some fine wire from one nail to another,” with his hands at her hair. He said to Claudette, “You pluck the strings up high near its throat,” with his lips at her pulse. He said to Helena, “You slide a glass bottle down it for tonality,” lifting her A-line skirt. “It’s simple,” Robert told each of us at dawn the next day. “Just like love.”

Leroy got back home at two in the afternoon. He stood his horse in the gravel thoroughfare, looking down on his younger brother. In one hand he held the fraying reins of the best tack he could afford at his pay, and in the other he carried a cumbersome box wrapped in layers of newsprint. Leroy asked his brother how long he’d been at practice.

“Since you left.” Robert dusted his knees and indicated the package. “That my present?”

“Expect so.”

Leroy told his brother to wait on the front porch until he’d taken care of his horse in the stall out back. Robert did as told. On about five minutes later, Robert knew his brother was coming close by the sound of him whistling an old ragtime ditty. Leroy appeared from around the corner with the newsprint package in hand. He took the bootworn steps of the porch two at a time, only to heave the present to his tenterhook brother four from the top. Robert thought on its contents for the moment. It could be one of those burlesque magazines, Photo Bits or Body in Art, he saw on the top shelf at the five-and-dime down the street. It could be the special kind of twill fedora with a paisley ribbon Leroy wore at a tilt when taking girls on the town. Robert hastily tore away the newspaper in sheaths of black and white, the crumpled headlines for May 8, 1923, announcing the recent ceremonial inauguration of Yankee Stadium in New York City and the possible ratification of a law requiring the Ku Klux Klan to publish a list of its members.

His birthday present was a Stella concert guitar. Its brown-finish wooden fingerboard included dot inlays along the frets, its sound hole had a rosette design, and its six-string configuration featured a classic tuner headstock: The instrument was beautiful, luxurious, and ghastly. A guitar meant Robert would actually have to play it; a guitar meant Robert would actually have to be good.

“Where’d you get the money for this?” he asked Leroy, whom we would later question through the bars of his cell at Angola, where he was serving 10-to-20 for bank robbery after a steady eight-year descent into iniquity. “They give you a raise at the lumber yard?”

“I tried my hand at the tables. Beginner’s luck.”

The first twelve years of Robert Johnson’s childhood, regardless of his present concerns, could be seen as a paradigm of musical development. At the age of nine he’d proven himself a quick study of the harmonica and Jew’s harp under his brother’s patient tutelage. At the age of six he’d glued Coca-Cola poptops to the soles of his saddle shoes and danced taps on the granite slabs in his neighbor’s barn lot. At the age of eight he’d taught himself the mechanics of percussion by slapping spoons against the flank of his thigh. What frightened Robert Johnson about owning a guitar, however, was its undeniable, inescapable portent of maturity. Guitars were for men.

“You got to name it,” his older brother said through a handsome grin. “Every guitar’s got to have a name.”

At the same moment Robert was going to tell Leroy he had no such inkling, he heard his own name spoken by someone standing on the sidewalk in front of the house. Robert squinted against the sunlight and wiped sweat from his brow what better to catch sight of a woman leaning against the mailbox stenciled with the counterfeit name of C.D. Spencer. The past years had been hard on her for certain, hair gone gray, cane in hand, face left wrinkly, but she still cut a powerful figure much the same. Robert gripped his guitar and managed to say, “Momma.”

Our husband spent the next few years living with his mother in Robinsonville, Mississippi, a sharecropper settlement in the northwest corner of the Delta. During those idylls of his youth—chopping cotton at the Abbay & Leatherman Plantation outside of a town called Commerce, reciting the alphabet at a one-room schoolhouse built along the banks of Indian Creek—Robert Johnson never forgot the strain of his life’s ambition. He practiced on “Julia” every chance come his way.

One afternoon when Robert was fourteen, his mother found him playing the Stella six-string in an empty bathtub left for rubbish in a field near their house. The acoustics of cast iron suited the instrument’s sound. Robert was busy learning how to use the key of a sardine can as a guitar pick, but he cut his song short when he noticed his mother crossing the field. She sat on the bathtub’s roll rim and said, “Fiddle sounds right sweet.”

“I guess so.”

“I mean it, dear heart.”

“I know so.”

“Listen here a minute. I’m sorry about what happened this morning. I shouldn’t ever do such a thing to you.” Julia’s eyes followed the trajectory of a bumblebee, but nary a flower blossomed along the ground. “It’s just that when you asked me about the thing you did, all grown up and the like, I realized you take after somebody I knew a long time back.”

“Take after who?”

“That’s why I’m sitting here talking to you now. Got something to tell you. It’s about time you were knowing about it. And I didn’t want Dusty to hear.”

It cannot be said Robert got along with his stepfather. Straw boss of roughly eighty-five tenant sharecroppers around Commerce, respectable deacon in a local congregation, and modest resident of Tunica County for all of fifty-one years, William “Dusty” Willis was given his nickname because he had a tendency to walk so fast a cloud of dust would billow around his feet and legs. He did not allow for spare moments. Dusty Willis thought of his second wife’s son as a spoilt city boy whose guitar was the devil’s tool. He called it a pitchfork.

“Dusty doesn’t want to hear nothing, Momma.”

“Anything.”

“Dusty doesn’t want to hear anything, Momma.”

“He’s done his best to raise you like you were his own son. Past couple years he’s kept food over your head and a roof on the table. But Dusty’s not your father. You never even met him.”

“How’s that now?”

“The father you know isn’t your real father.” Julia swept a cow killer from her threadbare knee-high, frowning at the bug’s coat of red and black fuzz. “You’re not a Spencer. You’re not a Dodds. You know you’re not a Willis. Your real father’s name was Johnson.”

Julia told her son about a “love affair” she had with “the kindest, gentlest man” around the time of her husband’s departure for Memphis. She told him how her husband, try as he might, never forgave the sin. She told him of her own guilt over the “union at night” whose only consequence worth mention was the “blessing of his birth.” At the end of his mother’s confession, Robert said not a word to her—he had questions plenty, but answers would come—even as she stood from the tub broken beyond repair, even as she left the grassy field scattershot with clover.

What stuck longest with Robert was the name of Johnson. During the years to follow, he felt it necessary to adopt the name as his own, but he couldn’t bring himself to tell anyone the truth. To Ms. Pamela Lafayette, headmistress of the Indian Creek School, he remained Little Bobby Spencer, the boy with poor eyesight and beautiful script who sat in the third row from the back. To Mr. Samuel Oglethorpe, overseer of the Abbay & Leatherman Plantation, he remained Dusty Willis Junior, a farmhand earning a dollar a day to wield a hoe through clumps of buck brush. Robert Johnson never told anyone his real name until the day he met our predecessor.

On Saturday, April 11, 1928, Robert Johnson decided he would run away from home. Such thoughts were nothing new. Earlier in the evening, just as usual, Robert’s stepfather had forbidden him to attend the Saturday night ball held regular in a barn behind the Robinsonville Mercantile, and later in the evening, just as usual, Robert put a row of feather pillows beneath his patchwork coverlet and snuck out his bedroom’s double-hung sash window. He had yet to get caught.

The Robinsonville Mercantile was a good hour away, but Robert made it there in forty-five minutes easy. Tonight was special. Son House and his crew, legends throughout the dance halls of the Delta, bluesmen of bluesmen, professionals along the circuits of the South, were expected to arrive from a gig in Fayetteville and begin their first set at nine o’clock. Although most Saturday night balls didn’t get up running ’til well past ten, “The Godfather of Blues Music” could draw an early crowd by virtue of reputation alone. Somewhere close to a hundred souls were milling about the dry goods stock when Robert arrived at the scene his stepfather would often refer to as the devil’s larder.

He joined a group of friends from the county, Johnny Boyd Johnson, Frank Diamond, Harpo Wells, Curtis Peters, Albert Tad Lipscomb, and Johnny Shines, who over the next nine years would accompany Robert to St. Louis, Charleston, Toronto, and New York. All of them were talking biggity about their talents in relation to Son House—“I can play circles around him” and “He got nothing hear-tell over me”—when the man himself walked through the crowd past them towards the barn. Afterwards, the boys scarce made a sound except until a girl standing near them did.

“Catmightydignifiedtilthedogwalkby.”

At first Robert thought she was speaking in the unknown tongue. Even though her words were intelligible, they reminded him, with their muddled vowels, with their blurred consonants, of the box suppers, protracted meetings, and tent revivals that had grown popular throughout the better part of the region. Robert observed the girl. She wore a blue-and-white gingham dress, soft furbelow grazing her kneecaps. The curvatures at her elbows, neckline, and ankles were as naked as the day Jesus flung them. She bore the evidence of store-bought soap, hints of sassafras oil, mint, lemon, salt, and vegetable tallow. At her side she held by suction of her thumb a Coca-Cola, its hobbleskirt bottle filled just partly with the original mix. Her breath suggested bourbon.

“My name’s Robert Johnson.” He came the closer. “What’s your name?”

“Virginia Travis.”

What he didn’t know at the time but would soon learn through conversation was that she had been born under a harvest moon sixteen and a half years earlier, her golden retriever’s name was Maybeetle Purslane Socrates, her father owned forty acres of good bottomland, her favorite flavor of ice cream was spumoni, and a childhood case of the mumps had taken her ability to hear.

“How can you tell what I’m talking at you right now?” Robert gave her a second. “How…can…you tell…what I’m…talking…at…you right now?”

“The same way I know what’s in a book,” Virginia said with laughter. She placed her index finger on the philtrum of his lip. “I know how to read, thunk you headly.”

Those last words sunk it for him. While ignoring the cat calls and dog barks from his friends, some apparently jealous of this girl’s beauty, others outright disdainful of this girl’s handicap, Robert slipped Virginia’s hand into his jittery own, walked through the lessening crowds, and entered the barn in time to witness Son House take a seat on a three-leg stool and strike the very first licks of the night. It wasn’t the only traveling band Robert had ever seen, but it certainly was a sight he’d ever laid eyes. At lead guitar, Son House, who years earlier had been a Baptist minister and who a year later would shoot a Texan allegedly in self-defense, channeled hellfire into his performance, hands nothing but a confusion of strum, sweat raining down on the fingerboard, eyes anything but steady in their aim, and voice railing against the authority from on high. At second guitar, Willie Brown, who would be the only person Robert Johnson said should get notified in the event of his death and who remains forever the “my friend-boy” referenced in the lyrics of “Cross Road Blues,” could hardly keep up to comment, his hands stumbling across the strings, his face contorted into concentration. The crowd sure did hully-gully on the dirt floor. They swung their arms like the tarnashun and they threw their legs like a hootenanny. One story has it that a baby fell out of its mother’s womb during a dance called Cloud Nine, the umbilical cord left to shrivel away on the ground’s layer of dust, manure, and straw. Another story has it that a steamboat deckhand bled from his ears without even a touch of soreness, the red stain on his collar so elaborately patterned that people thought he’d been given one of the Five Sacred Wounds.

“Why would you come to these things,” Robert said to Virginia, “if’ing you can’t hear what they play?”

Virginia stared at one of the barn’s supportive beams. She took Robert’s hand and placed it on the wood. The music’s vibrations shimmied through his fingertips. She pointed at the ground, stomped her foot, and nodded at the crowd. The dance’s rhythms bound up his leg. Robert shook the more at the memory of her touch.

With a smirk Virginia said she wanted to dance and left him on his own with a fresh erection. The barn was hotter than all get-out. At close to 102.4 degrees, the air could not be distinguished from the people in it, and at close to 98.6 degrees, the people could not be distinguished from the air around them. Robert lost Virginia. Her invention of style should have set her apart, but he could not tell anything from the mass of bodies in motion.

All that survives of Virginia since she went to her reward is a sepia-tone cameo found in a drab pewter locket. The very features that stand out in the small photograph, the delicate coincidence of her fingers and hair, a tiny pearl of sweat at her temple, the russet brown coordinating her skin and eyes, allowed Robert to find her in the crowd at the Saturday night ball. The flower vine of his pulse, as he put his hands at her lower back, as he set his feet in accord with her own, scaled the latticework of his desire. They danced in the company of others. They danced in the company of others. They danced in the company of others. The realization of what Robert was feeling did not occur to him against the twelve-bar arrangement so essential to the origins of blues music, nor did it occur on the 3-4-3 beat he would eventually master in his own songs. He fell in love between sets.

Outside, where they sought the cool of midnight air, Robert pulled a harmonica from his pocket, cradled it in his palms, and serenaded Virginia with sound. She held her hand against his chest so she could register the notes of music. At the end of the song, she leaned towards his ear and whispered, “Be the fool.”

“What?”

“Beautiful.”

The marriage ceremony of Robert Johnson and Virginia Travis would be held at the Commerce Missionary Baptist Church on Sunday, January 21, 1929.

What little we know of Robert and Virginia’s life together was drawn piecemeal from our husband at those rare times of his capitulation to sorrow, remembrance, and whiskey. Their marriage took a beat all its own. Although chores on the homeplace kept them apart throughout the day—her churning cow milk into sweet butter, him thatching raw burlap to burst pipes—Robert and Virginia spent their nights sitting with their hands at common prayer before the commencement of a meal, strolling the countryside in step to the songbirds of sundown, and whispering persiflage ear to ear in the candlelit hours after retirement to bed. Soon enough, one thing leading to another, another leading to one thing, our predecessor found herself in a family way.

They’d been wed ten months when Virginia went into labor. On his arrival home from work at the Abbay & Leatherman, where he still got paid a meager wage for tending the scraggly cotton fields and where he still got lost in his head arranging clumsy song lyrics, Robert opened the door of his home, sump mud stuck to his boots, guitar slung across his back, to find his wife sitting in a puddle of liquid on the floor. Her fingers were splayed across her belly. Her breath came and went on the quick. Her eyes were glazed to the light. Robert fell to his knees, took his wife’s hand, and said, “Is it time?”

She did not answer out loud. Virginia let her uncertain gaze travel from her husband’s face wrung into confusion, across her dress spotty at the waist, across her hands shaking beyond control, to the puddle on the floor marbling with far too much blood. In it she had written with her finger a single six-letter word.

Within the hour Robert had reached the doctor’s office by foot and ridden with him back to the house. Dr. Netherland brought a midwife for assistance. At the sight of Virginia on the floor, agonized, bloody, petrified, both the doctor and his midwife, the former arranging steel instruments and lifting the patient’s wet skirt, the latter fetching a white-cooper’s bucket of spring water, filling a stockpot on the sheet-iron stove, and stoking the firebox until the water hit a boil, reacted in a manner unlikely, inhuman, and unearthly in comparison to Robert Johnson, whose limbs went rigid and whose face went slack, his only audible reaction the subterranean moan of a young man come to his first absolute grief.

“You have to be staying outside,” the doctor told him. “I can’t be having you in here.”

“Why?”

“Boy.”

“Okay.”

“Miss Burchill, bring me the chloroform pills,” the doctor told her. “Help me get this woman on the bed and out of this muck.”

On the porch, Robert got a tenuous handle of his constitution, trying not to listen. A barn owl took silent flight from its perch in a lone cedar and sank its talons into some opossum whose shriek broke the sylvan calm. Junkyard dogs on a nearby farm howled and barked and growled against the darkness of cotton fields at night. A pair of whitetail fawn stood at a salt lick until the rustling of a copperhead near their feet set them to gallop in tandem far from earshot. Around the other side of midnight, some two and a half hours later, Dr. Netherland opened the door and waited for Robert’s company.

“Your wife had some complications made a struggle of the birth.” The two men regarded each other. “I have some news may be hard to hear.”

“I know.”

“The child.”

“I know.”

“The mother.”

“I know.”

“Even if we’d gotten here before it begun, I don’t know as it could’ve gone about otherwise.” The two men looked away from each other. “Had you and the missus given your child a name? I need it for the certificate.”

Our husband kept so quiet. At plain sight of the doctor and his midwife, one removing his sleeve garters in dire need of a wash, the other spreading muslin cloth atop a willow basket, Robert stumbled down the front porch’s creaky steps wrought slantwise with lost-head nails, caught his breath, walked among crickets whose chirping foretold the approach of dawn, hung his head, and stopped in tall grass overrun with nut sedge, foxtail, and coffee weed. He held himself against the cold. He sank his gaze to a low spot. Whatever his thoughts were throughout the night—we do not know for certain if he cursed God, but we do know he had ample provocation—Robert Johnson’s son remains nameless to this day.

He knew it was the end, but he could not end it. At Scotty Jay’s Rumpus Room near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, one of the roughest honk-a-tonks within legal distance of the parish limits, a whorehouse with no whores, a pool hall with no pool, where men came to drink and gamble but nothing much else except be men, Robert Johnson was dealt a string of hands that put him $157 in the hole. All that was left to whatever name he was going by at the time sat on the worn felt of an old card table in the dark parlor. Two white chips at twenty-five cents apiece, one red chip worth five dollars, two blue chips at a dollar each. Anybody of sound reason would have called it a night.

“Praise the Lord almighty above if Robert isn’t my new favorite player,” said Ferris Thurgood, cardsharp and hothead, who’d once cut a priest’s vestigial tab clean in half for fobbing his excess chips in the manner a cheat would some stray ace. He said, “Feel free to sit your raggedy ass across from me anytime you want.”

“Ain’t that wit.”

“I can’t feature why Robert here always got that guitar with him,” said Woodson Potter, yards of rye in his gut, sideiron on the table, plug of chaw in his lip, whose minacious smile drew attention from a face ugly with pox scars. He said, “Hasn’t played a lick since I known him. Must be his lucky charm.”

“Just you wait.”

The evening’s game was five-card stud. Although he would eventually curtail the progress of such a low habit, Robert could never fully quit his compulsion. We know from experience. Around about the time of their introduction, he taught Claudette a standard game variation, “Follow the Queen,” whereby every card dealt face-up following a queen becomes wild until the appearance of another queen. During their courtship, he gave Tabitha lessons in community card play. During their engagement, he gave Betty lessons in cards-speak split pot. Around about the time of their marriage, he told Mary Sue how the king of hearts is often known as a suicide king and how the queen of spades is often known as a bedpost queen. We never gave it much mind.

On the night at the bar, still a few years from his proposal to the first of us, Robert Johnson, strung on all sides by railbirds anonymous in their numbers, played Ferris Thurgood and Woodson Potter in a type of five-card stud called “Dr. Pepper Poker.” The popular soft drink’s slogan, “Drink a bite to eat at 10, 2, and 4 o’clock,” inspired the special variant in which the ten, two, and four cards were wild.

Each of the players placed their ante of fifty cents at the center of the tabletop. Woodson was on the button. First he dealt a card face-down, and next he dealt a card face-up. At sight of his ace of clubs and eight of spades, Robert tossed five dollars worth of chips into the pot, a goodly portion of his final stake, and at third and fourth street’s advent of a queen of diamonds and an ace of spades, he raised the pot by another fifty cents in chips, leaving him with only two dollars. The others called him each round. Robert felt there must be a cinch hand somewhere in his draw, but the deck would not oblige him beyond the nut. His next card, lest he come a cropper, surely had it. Thus, on fifth street, his pulse slowing near to a crawl, his palms going dry as goofer dust, Robert was dealt an eight of clubs to complete his two-pair hand of dark suits.

“Look at him now, I tell it, look at him now,” either Ferris or Woodson said as both of them raised the pot higher than their opponent’s last two dollars. “Robert got the malaise. He got the malaise like he never been to Louisiana.”

He’d been to Louisiana all right. Since our predecessor’s death less than two years back, Robert Johnson had passed transient throughout the counties and states and townships of the South, never once arriving without the same intention in mind, never once leaving without failure to achieve it. Much can be told of a man by the way he goes about killing himself. Robert stole at the glint of his knife every kind of transportation along the Natchez Trace, steam railcars to phaetons to horseless carriages, each vehicle’s Klaxon bell scaling the pitch of his mad laughter. He was known then as Carter. Robert committed acts of congress with a host of slatterns from Storyville, mulattoes and high browns and darkies, only some of whose standards of hygiene involved the protection of a pessary. He was known then as Jones. Robert kissed the dainty hand of a plantation owner’s beautiful daughter outside of a Woolworth’s Store and provoked a lynch mob into searching every alley of Frontage Street for “the sambo who raped a debutante,” only to escape their howls for mortal retribution by putting on white face along with a black hat and kvetching Yiddish polyglot in mimicry of a minstrel show remembered from his Memphis childhood. He was known then as Goldstein. Robert was arrested once in Georgia for expectoration on a public sidewalk and was found guilty three times in Alabama for collusion to vagrancy and was sentenced twice in Florida for public intoxication. He was known then as Smith. Robert Meriwether commandeered an Oldsmobile Curved Dash over the side of a suspension bridge straight into the shallow chop of the Black Warrior River. Robert Simpson stood in a pasture of Yalobusha County during a thunderstorm with a steel railway sleeper raised high above his head. Robert Boswell stenciled zigzag scars on his thin wrists with a Sheffield straight razor pinched from J.P. Nettle’s Shaving Shop on Fat Tuesday. All the same, despite the many signs of providence—his unconscious body burping from the brown waters due to buoyancy from a geological salt inclusion, lightning bolts melting rivets on a distant barn’s tin roof, his blade cutting but scratches because its previous owner was a barber compulsively frugal with his tools—our husband considered his own survival to be nothing more and nothing less than the hardest, worst, dumbest luck.

“How far will this get me?” Robert put his guitar in the pot. “I’m feeling fortunate this evening.”

Between piles of chips worth about thirty dollars, the Stella concert guitar, later sold at Sotheby’s for $8,450 not including tax, sat at the center of the table, kerosene light reflected in its varnish, cheroot smoke wafting over its strings. Ferris and Woodson exchanged a look of confusion on the mend. At the moment one of them was about to speak, a voice from the back of the crowd said, “It’s a damn sight for a bluesman to gamble his guitar.”

Robert couldn’t believe it from make-believe. That voice cured by cheap whiskey, those wrists stained in black powder. This man could not be his brother. The dim bar did not allow for easy sight, but this man could not possibly be his brother. Robert told him as much.

“I should say the same,” said Leroy, only two months, three weeks, and five days from his induction to the country’s worst hoosegow, where decades later he would join a group of inmates, “Angola’s Heel Street Gang,” who cut their own Achilles’ tendons in protest of the poor conditions. “I think we’re both about close to bottom.”

“What’re you—”

Robert’s words were cut short by the realization he had accidentally laid all of his cards face-up on the table. Woodson and Ferris in turn laid down their own cards, two at a time and then one at a time, the former holding a straight flush with queens high, the latter holding a full house of jacks over nines. The demure smiles on each face card seemed a weird simulacrum of each man’s devious grin. It suddenly became apparent that Robert Johnson, who would later win two Grammy’s within sixteen years, who would later be among the first thirteen musicians inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, who would later go multi-platinum three times with only twenty-nine songs, had lost his guitar in a single hand of poker.

Our husband could not find the words, let alone the actions, though his opponents had no such problem. Woodson gave his winnings a home at his side as Ferris put on a spectacular show of flatulence. Finally, after he knocked over his chair while standing up, after he mumbled some such nonesuch to his brother’s offer of help, after he dribbled sweat on the table while backing away, Robert made to take leave of Scotty Jay’s Rumpus Room. The upstairs girls marked the cross from shoulders to forehead. The knuckledusters searched their cups for a sign of divination. On the porch, leaning over the scrapwood rail and aiming for a dandelion patch, Robert evacuated the contents of his stomach, including five pints of the house lager, three quail eggs, the lobe of a pig’s ear pickled in pink vinegar, a dozen cove oysters, the oily shreds of tobacco loosed from a cheap cigarette, and seven wheat-head pennies he always swallowed before a night of gambling. He retrieved his last seven cents by hand.