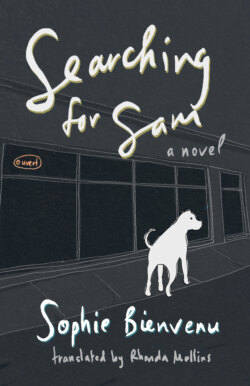

Читать книгу Searching for Sam - Sophie Bienvenu - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеI REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME SOPHIE TALKED TO me about Searching for Sam. We were in a rickety little plane, heading to the forty-second Salon du livre de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue, in La Sarre. I so liked the amoral Lolita from her first novel Et au pire, on se mariera (published in English as Worst Case, We Get Married) and her sublime style that I was afraid I wouldn’t like her next novels as much. It was early; we were nibbling on Japanese peanuts. We chatted about music and complained about the deafening drone of the puddle jumper. I showed Sophie a crazy video montage of Céline Dion dancing to Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky” and she started telling me about a boy looking for his dog. I have always preferred cats.

At the airport, as soon as we deplaned, we got in a minivan that would take us to the ceremony for a regional young readers’ award, the Prix des lecteurs émergents de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue. It was a jam-packed schedule, and time was tight. We immediately headed out onto Abitibian soil. The sky was ice blue, like the colour of Nelly Arcan’s eyes, and the grass was yellowed. We drove, a ribbon of asphalt streaming behind us. At one point there was the loud crunch of sheet metal, as if the body of the van had been hit. We stopped. Through the window, I could see a wheel continuing its trajectory along the road, all the way to the ravine alongside it. Sophie exclaimed: “The wheel has désolidarisé from the car” – “se désolidariser” being French verb that suggests breaking ranks, heading in a different direction. The perfect word, uttered loud and proud, to refer to a tire run aground in the dry mud of a ditch. It was as good as inventing a word as needed, such as when she uses “cwet” (“frouillé” in the original, a mix of “froid” and “mouillé”) to describe the cold, wet nose of the pitbulls she so loves.

The airport was forty minutes from La Sarre, and we were barely a quarter of the way there. All we could do was wait for reinforcements. It was freezing cold. We walked to the little convenience store on the side of the highway, where we bought candy and shirts with spectacularly kitschy wolves on them. We missed the ceremony for the award for which we were finalists – Simon Boulerice’s Javotte won, in any event. But the trip to La Sarre was worth it for the epic shirts and the fresh air.

Sophie went back to Abitibi-Témiscamingue. She told me that she had written her first poem after visiting the Refuge Pageau, a shelter for injured wild animals that works toward releasing them back into the wild, or, when that fails, offers them a home. Sophie’s novels are filled with vulnerable creatures. She spends her time with those on the fringes, the feral. I picture her in the snow and the scent of the fir trees, as at home with the grey wolves, coyotes, and birds of prey as she is with her dogs.

Sophie has a knack for taming those thought to be aggressive, who have a loud bark and who occasionally bite. She senses their most intimate suffering and the cause of their hurt. In Searching for Sam, she gives shelter to a young man who is living hand to mouth in the streets of Rosemont. They share a love of pitbulls. His name is Mathieu. In real life, Sophie helped a young homeless man named Mathieu pay for the vet for his dog; he confided in her, told her about his daily life, its obstacles and moments of joy. She didn’t change his name, but did change the name of the dog in Searching for Sam, a raw novel that broke my heart and then healed it.

Sophie is one of few authors who can make you laugh and cry in a single sentence. And she does it without judgment, without falling into gloom and pessimism, and in a spoken language that has panache. With her novels, written in her distinctive style, readers see the world through the eyes of protagonists who generally don’t have a voice. She gives them their own tailored vocabulary, in the tradition of J.D. Salinger, Philippe Djian, Réjean Ducharme, and Romain Gary – her favourite authors, to whom she is sometimes compared. Sophie offers readers the opportunity to have a powerful human experience. They search for Sam with Mathieu and the quest becomes an obsession for them, too. Readers suffer with Mathieu, and it feels unbearable. “Is it a difficult novel?” I am asked about Searching for Sam. It’s a novel that is both sweet and tragic, that leaves no one indifferent. Even those who prefer cats. “But is it realistic?” some ask, as if realistic were the path to truth. In real life, Mathieu Gaudreault, the author’s wandering muse, died in a car accident on December 21, 2014, on his way to celebrate Christmas with his family. He had a chance to read Searching for Sam, which is dedicated to him and “to all those who lost their way.” He left behind his six-year-old daughter. His dog Fœtus was adopted by a friend. Sometimes life is more brutal than fiction.

Mathieu Gaudreault’s neighbours from Rosemont paid tribute to him in the winter of 2015, gathering in front of his spot, at the corner of rue Masson and Cinquième Avenue. Passersby miss his humour, his witticisms, and the twinkle in his eye. It’s life, death. And it’s literature. This gripping novel, the paper voice that still echoes in my head months after I turned the final page, is a stunning memorial to Mathieu’s life.

—MARIE HÉLÈNE POITRAS

Montréal, April 16, 2015