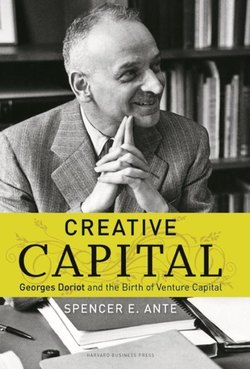

Читать книгу Creative Capital - Spencer E. Ante - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE ROOTS

Оглавление(1863–1898)

ON A SUNNY AFTERNOON in the spring of 1913, Georges Frederic Doriot ran as fast as he could all the way to his home on the outskirts of Paris. Young Georges and his family lived in Courbevoie, a bustling town twenty miles north of France’s capital nestled along the eastern bank of the Seine River. Thanks to its proximity to the wide ribbon of water, Courbevoie had established itself as a manufacturing center. In factories sprinkled around town, companies produced automobiles, perfume, and other products in their more affordable environs, and then shuttled their handiwork down the river to the big city.

It was the end of the school year and thirteen-year-old Georges was running home because he had good news to share with his family. A student at Coubert 7, Courbevoie’s public secondary school, Georges disliked school because he was always afraid of not doing well and saddening his parents, particularly his demanding father.

But today was different. Georges had excelled in his classes, and had the paper to prove it. He excitedly careened around boulevard corners and shortcut across intersections, nearly colliding with several flâneurs strolling down the street. It was only when he reached Rue Franklin, a block from the walled garden of his family’s home, that he paused long enough to savor the honor embossed on the scroll he cradled in his sweating palm: Georges had placed second in his class at the École Communale.

It was an award certificate—the first such honor he had ever received. Beaming with pride, he couldn’t wait to share the good news with his family. Educational achievement was prized highly in the Doriot household. His father and mother would be pleased with him, he was sure. And so he resumed his dash for home.

Camille, his doting mother, responded as Georges had expected. An educator herself, she knew the value of supporting the achievements of young, insecure children. She embraced the radiant Georges with a warm hug, gave him a laudatory pat on the head, and set out a generous serving of homemade cookies that marked special family occasions. But Auguste, his stern father, had quite a different reaction. In stark contrast to Camille, Auguste seemed unimpressed with his son’s award. He acknowledged the certificate with only a cursory glance, nodded perfunctorily, and then fixed his son with one of those chilling stares of appraisal. “And why not first?” asked Auguste.

Auguste’s voice was calm but his words were a blow to Georges’s heart. And his father’s cool stare was more painful than any punishment Georges had ever received. Staggered, Georges didn’t know what to think, or how to react. He had expected congratulations. He had expected his father to be proud. Instead, he was knocked back on his heels, put in his place. Bewildered and humiliated, he fled to his room, tears welling up in his eyes. His glorious triumph had ended disastrously. Why, Georges wondered? Why did I disappoint father?

It was an experience that could have scarred him for a long time. But as Georges calmed down and reflected on the situation, he began to understand the reasons behind his father’s behavior. His father, he would tell a friend years later when recalling the incident, was not concerned that Georges had failed to achieve first place honors in his class at École Communale. No, he was concerned that Georges was happy placing second. To Auguste, a famous automobile engineer who had raised his children to strive for excellence in everything they did, celebrating anything less than the best possible result smacked of contentment. And contentment, Auguste believed, is a state of mind that recognizes no need for improvement. As Georges came to realize, his father’s seemingly cruel question was actually a well-meaning parent’s method of challenging their child to reach the stars.

It was a challenge he never forgot, and an experience that some friends theorize was responsible for driving Georges Doriot to extraordinary accomplishments later on in his life. Georges Doriot would never again be satisfied with being anything less than the best. Not in himself. Not in others. Not in anything.

When Auguste Frederic Doriot was discharged from the French Army in the fall of 1889, he was a young and ambitious man who harbored great hopes and dreams. Up to this point, however, they had been dreams deferred. Doriot was unfortunate in that he had to devote five years in the prime of his youth to the military. And yet he was also lucky. He happened to serve in the Army during one of the few periods in nineteenth century France that was not racked by war, revolution, or civil unrest.

In 1889, France was in the middle of its most peaceful period of the modern era—still stinging from its defeat in the Franco-German War of 1870–1871, when it relinquished European hegemony to the newly constituted German Empire. The terms of the Treaty of Frankfurt were harsh: an indemnity of five billion francs, plus the cost of maintaining a German occupation army in eastern France until the indemnity was paid. Most distressing, Alsace and half of Lorraine were annexed to the new German Empire. Then, a few days after the Treaty was signed, France tore itself apart when a civil war broke out during the rebellion of the Paris Commune.

Still, after its war with Prussia, France would not see another conflict or revolution until the early twentieth century. There would be no more “Bloody Weeks” for a long time. So after putting in his required years of service stationed in the armory of Bourges and Versailles, then the seat of the French government, Doriot left the army, all of twenty-six years old, in good health and spirits, with his homeland getting back on its feet.

Auguste had something else going for him: he had lined up a job for himself at the prestigious Peugeot Company. After his discharge from the Army, Doriot headed back home to Valentigney, a beautiful village in northeastern France near the borders of Switzerland and Germany, and the home of the Peugeot Company’s factory and cooperative store. While the majority of the villagers in Valentigney were farmers, many residents also worked in the factory. Indeed, most members of the Doriot family worked there at one time or another, including Auguste and his father Jacques Frederic Doriot.

Originally part of the Holy Roman Empire, Valentigney sits on the western bank of the attractive Doubs River. In the late seventeenth century, Louis XIV acquired the province in which Valentigney resides, Franche-Comte, following the Dutch War of 1672–1678. Louis XIV coveted the province because it provided the ancient regime with a buffer on its eastern border, helping to secure the safety of Paris. Turning eastward, Auguste could look over the crumbling Roman aqueducts and green forests and rolling hills of the Doubs district. And as he gazed over the horizon, he could marvel at the low, crenellated ridges of the Jura Mountains ranging across the Franco-Swiss border like some giant humpback whale.

Though it was a classically picturesque French village, Valentigney was unique in at least one respect. While nine-tenths of the French population was Roman Catholic, Valentigney was one of the few areas in the country that was completely Protestant. In fact, the district was so devoid of Catholics there was not even a single Catholic Church in the village. Later on, Georges, Auguste’s first and only son, fondly recalled his hometown and the industriousness of its people: “I remember it with a great deal of feeling. It was a wonderful world. People were not rich; they had to work for everything they had. They went to church very regularly and the Protestant minister was a kind and very respected man with a good education.”

The architecture of the village reflected the area’s working class roots. In the late nineteenth century, the typical house in Valentigney was a simple but sturdy structure built of stone and red roof tiles, and was encircled by a low stone wall, allowing passersby to peek over, luxuriate in the lush gardens and chirping birds, and smell the flowers.

This was the bucolic yet busy setting that Auguste returned to after five years in the Army. Auguste, the next-to-youngest child of a family of eight children, was born on October 24, 1863, in Sainte-Suzanne, a village in the Franche-Comte province about a dozen miles northwest of Valentigney. Auguste’s father Jacques, who had been a farmer in the early part of his life, worked his way all the way up to become the foreman of the Peugeot factory. In 1878, when Auguste was fifteen, Jacques arranged for him to become an apprentice fitter, or metal worker. Auguste worked in the factory for six years before he was called to join the Army. Now, back in Valentigney, Auguste could not have been more eager to return to the Peugeot Company.

If there was one thing that brought joy to Auguste, it was the pleasure of a hard day’s work. Photographs of him in his middle age show a man of medium height and solid build with a very serious look on his face. His most notable features were a strong Gallic nose, large ears, and a thick black moustache that was popular during the day. “My Father was a very wonderful person, extremely quiet, very thoughtful, very kind, but very strong,” recalled Georges. “He was a terribly hard worker. When he was young—I know this from my mother—he had worked as many as twelve to fourteen hours a day and he had still kept on doing that.”

By going back to work for Peugeot, Auguste showed wise judgment. The Peugeot clan had first settled in the east of France in the fifteenth century and, like most elite clans of that time, drew its wealth from vast tracts of land. In the eighteenth century, the Peugeots expanded into windmills and textile mills. In 1810, the brothers Jean-Pierre and Jean-Frédéric Peugeot converted one of those mills into a steel foundry for manufacturing saw blades, thereby creating the Peugeot Company.

By the late nineteenth century, the brothers had created one of the most well-known and successful companies in France. Building on their textile and steel plants, the family transformed their namesake into a diversified manufacturing concern with expertise in producing household tools such as kitchen utensils, coffee grinders, sewing machines, and various other items. But much of the Peugeots’ wealth came from a more unusual source: they cornered the market in women’s corsets, because they alone possessed the secret of manufacturing the special steel needed to stiffen these Victorian Age garments. Through hard work, a keen sense for spotting opportunity, and a flair for innovation, Peugeot forged a reputation for making quality products.

The Peugeot brothers were fortunate in that the family business was large and profitable enough to finance their expansion into new industries, for in the nineteenth century, financial markets were crude and entrepreneurs had a difficult, if not impossible, time raising money for new ventures. After all, the concept of the entrepreneur was relatively new, having been first introduced into economic theory by the underappreciated philosopher-economist Richard Cantillon in his remarkable treatise Essai sur la Nature du Commerce en Général, written between 1730 and 1734. In the nineteenth century, entrepreneurs virtually disappeared from classic economic and political thought thanks to the lack of financial support for their undertakings and awareness of their importance to the economy.

The idea of venture capital was even less developed. In fact, it was not until the early twentieth century that the term venture capital was first popularized. Sure, there were a multitude of individuals throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who were small saver-investors. They typically congregated around large European port cities and were prepared to take modest risks, such as sending a few goods on a departing ship. But by and large their meager savings were invested more readily into government bonds.

Banks, which had existed since antiquity, were also of little to no help to a struggling entrepreneur. It wasn’t until the Bank of England was founded in 1694 that banks began offering loans and advances of credit. Until that time, large public banks such as the Bank of Barcelona or the Bank of Genoa only handled deposits and transfers. Still, banks were not in the business of providing equity financing. It was too risky.

The most powerful bank of the nineteenth century, the House of Rothschild, is a case in point. In the first part of the century, the Rothschild family rose to power, transforming a small merchant bank in Frankfurt and a clothes exporter in England into a multinational financial conglomerate by lending money to war-torn, cash-strapped European governments. Later on, they created the biggest bank in the world by pioneering the creation of the modern bond market, enabling British investors to buy internationally tradable bonds of other European nations with a fixed interest rate. The Rothschilds made a colossal fortune by making these loans and by speculating on their rise and fall.

Occasionally, the Rothschilds invested their capital into a new business. But when they did it was to help finance major infrastructure or natural resource development projects. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the Rothschilds used their ample resources to become a dominant force in the finance and construction of European railways. Between 1835 and 1846, the Rothschilds contributed nearly 38 percent of the capital invested in thirtytwo French railway concessions.

By and large, though, early European financial enterprises like the House of Rothschild were attached to their privileges, thoroughly conservative, and not interested in the future or fomenting change. In other words, they had nothing to do with venture capital as we know it today. “A commercial bank lends only on the strength of the past,” said Doriot in one of his favorite maxims about the venture capital business. “I want money to do things that have never been done before.”

The earliest instances of the initial financing of groundbreaking enterprises were primarily found in America. The first major modern communications technology, the telegraph, was financed by a small group of wealthy investors. In 1845, Samuel Morse hired Andrew Jackson’s former postmaster general, Amos Kendall, as his agent for locating potential buyers of the telegraph. Kendall had little trouble convincing others of its potential for profit. By the spring of 1845, he had found a small group of investors who committed $15,000 to form the Magnetic Telegraph Company.

One of the most famous inventors of all time also got his big financial break from two wealthy individuals. In the early 1870s, Alexander Graham Bell, a Scottish immigrant who developed an early fascination with the science of acoustics, became a professor of Vocal Physiology and Elocution at the Boston University School of Oratory, a school for mute children. In addition to teaching, Bell was driven by a desire to cure his mother’s deafness and thus continued his research in an attempt to find a way to transmit musical notes and speech.

During the fall of 1874, Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders, parents of two of Bell’s students, found out that Bell was working on a method of sending multiple tones on a telegraph wire using a multi-reed device. Sanders, a successful leather merchant, began to underwrite some of Bell’s expenses. After hearing about Bell’s experiments, Hubbard, a wealthy patent lawyer always looking for opportunities to improve things and make a dollar in the process, saw the opportunity in developing an “acoustic telegraph”— in other words, a telephone. He drafted a partnership agreement between Bell, Sanders, and himself and began to financially support the inventor’s experiments.

On March 7, 1876, the U.S. Patent Office issued a patent to Bell covering the “method of, apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically … by causing undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound.” Bell and his backers Hubbard and Sanders offered to sell the patent to Western Union for $100,000.William Orton, Western Union’s cigar-chomping robber baron president, balked, countering that the telephone was nothing more than a toy. But after Hubbard organized the Bell Telephone Company in June of 1877 and hundreds of businesses began leasing the phones, the unscrupulous Orton ignored Bell’s patents and began to manufacture a telephone that incorporated the inventions of Thomas Edison and other inventors. Western Union had the considerable advantage of piggybacking on the company’s already existing telegraph network, easily stringing telephone wires to the telegraph poles.

By this point, Thomas Sanders had poured $110,000 into Bell’s work and had not seen a cent in return. And Bell Telephone was facing a serious cash crunch and a vicious illegal competitor. So Hubbard did the only thing he could to save the company: he launched a lawsuit against Western Union, accusing the company of patent infringement. It was a classic David and Goliath battle, the first major lawsuit of the age of modern communications. “The position of an inventor is a hard and thankless one,” wrote Bell to his wife during the middle of the trial. “The more fame a man gets for invention, the more does he become a target for the world to shoot at—while no one thinks the inventor deserving of pecuniary assistance.”

After company lawyers finally convinced Bell to provide his expert testimony, Western Union lawyers knew they stood no chance of winning the case. On November 10, 1879, Western Union signed an out-of-court settlement transferring at cost all telephones, lines, switchboards, patent rights in telephony, and any pending claims to Bell Telephone. In return, Bell Telephone agreed to stay out of telegraphy and to pay Western Union 20 percent of all telephone receipts until Bell’s patents expired. Now that Bell Telephone owned a monopoly on telephone service, its stock zoomed from $65 per share before the suit to more than $1,000 following the settlement. The humiliating defeat led Orton to admit that if he could snare the Bell patent for $25 million it would be a bargain.

In late-nineteenth-century Europe, another innovative new technology was poised to explode—the horseless carriage. With the backing of the family fortune, a young member of the Peugeot clan seized on the opportunity—a move that would ultimately catapult the family’s company into the ranks of the world’s leading conglomerates. Born in 1848, Armand Peugeot exhibited an interest in machines from an early age and went on to study engineering at the prestigious École Centrale Paris. After graduating from the École, Armand visited Leeds, then the heart of manufacturing in Britain, and came back convinced that the future of horses as a means of transport was not very bright.

In the early 1880s, Armand first pushed the family into bicycle manufacturing. Later in the decade, he teamed up with Leon Serpollet, a young engineer who had built a reputation as an expert in steam engines. In 1887, Serpollet had caught Armand’s attention when he built a single-cylinder steam engine almost entirely out of scrap parts and fitted it to a pedal tricycle. Armand subsequently provided financing to Serpollet to create the world’s first steam-powered tricycle. In 1889, at the World’s Fair in Paris, Serpollet introduced his invention, making Peugeot one of the pioneers of the proto-automobile.

At the same World’s Fair, Armand noticed the debut of another new machine that he thought showed even greater promise than the bicycle. The German engineer Karl Benz had introduced his Motorwagen Model 3—a carriage with wooden wheels and a gasoline-powered engine. Today, thanks to the 1886 Motorwagen patent, Benz’s machine is officially recognized as the world’s first automobile.

This was the hothouse of innovation that Auguste Doriot stumbled back into in 1889 when he returned to civilian life and the Peugeot factory. Every successful man can usually point to a mentor that helped guide his career. For Auguste Doriot, that man was Armand Peugeot. Armand recognized Auguste’s mutual fascination with machines and with the future, and, shortly after his return to the factory, sent Auguste on a series of apprenticeships in order to learn the latest techniques in automobile design and engineering and gas-powered “explosion” engines, as they were called at the time.

In 1891, Auguste finished his apprenticeships and returned to a new Peugeot factory in Beaulieu. He immediately set about working with the top engineer of the company, a gentleman named Louis Rigoulot, and began installing Daimler engines into the first Peugeot cars. “The beginnings were rather arduous,” said Auguste. “We had no machines except for those which served the manufacture of bicycles.” But despite numerous obstacles, the two men built several successful prototypes of a four-wheeled “quadricycle.” Armand rewarded Auguste’s hard work and ingenuity by promoting him to foreman of the factory. But Armand had another important assignment for Auguste, one that would elevate his stature and name to an even more formidable plane.

In September of 1891, Pierre Giffard, editor-in-chief of Le Petit Journal, a well-known French newspaper, staged the first Paris-Brest et Retour—a grueling 750-mile bicycle race that took riders from Paris all the way to Brest, at the tip of Brittany, and back. The race was a media coup for Le Petit Journal, generating a significant circulation increase.

Inspired by the success of this event, Armand Peugeot struck upon a brilliant idea. To create a successful business, car makers had to first prove that these strange machines were a reliable, safe, and effective means of transportation. The best way to prove such matters, Armand realized, was through a car race. So Armand asked Giffard if he could enter his quadricycle into the next retour. Giffard agreed and instructed the race agents to record the trip of the quadricycle as well as those of the bicycle racers. This ensured Peugeot would have independent proof of his car’s passage—and reliability.

Charged with the success of this mission were Rigoulot, the engineer, and Doriot, the foreman who doubled as the driver of the quadricycle. In these days of global jet travel, the difficulty of such a journey is hard to imagine. A trip of this length in a car had never before been attempted. The previous distance record was set by Serpollet who had traveled about two hundred miles from Paris to Lyon. Rigoulot and Doriot were attempting a fifteen-hundred-mile journey across a much more varied and challenging expanse of terrain. It was a bold and risky test that could easily backfire, ruining their reputations.

At ten o’clock in the morning, Doriot and Rigoulot set out for the first leg of their trip, from Valentigney to Paris. It was about a three-hundred-mile drive. They filled their car with tools, luggage, and a few water tanks. The Type 3 was powered by a two-and-a-half horsepower engine from Daimler and had four gears with a reverse gear.

Trouble struck early. Because the gas tanks were placed too low, the wicks of the headlamps were not receiving enough gasoline, and they were burning up. The two devised the “especially ingenious idea of covering the [gas tank] with fresh grasses in order to maintain it at the lowest possible temperature.” This solution helped gasoline reach the lamps more easily and it improved the flow of the fuel throughout the engine so the gears worked more smoothly.

Although the car reached speeds as high as thirteen miles per hour on flat stretches, it slowed down on hills. Auguste would throw the car into first gear, which reduced the speed to a near crawl. On very steep hills, while Doriot drove, Rigoulot followed the car, ready to push it if the motor stopped. But, happily, the motor chugged along.

Over the next few days, the two continued their journey. Along the way they slept in small French towns with charming names such as Coutrey, Bar-sur-Aube, and Provins. Three days later, after reaching Paris at one o’clock in the afternoon, the two men “made a triumphal entry” at the factory of Panhard-Levassor, another innovative French car-maker. Armand Peugeot greeted them with a big smile. Their average speed during the first leg was a respectable eight miles an hour.

A few days later, full of confidence, the two set out to establish the Paris-Brest record. At the time, there was no such thing as a gas station. So as a precaution, Doriot and Rigoulot had Peugeot employees place fuel supplies in advance of their arrival with railroad stationmasters every sixty miles or so. As it turned out, the stationmasters were often afraid to keep the gas for the racers for fear it would catch fire. In those cases, Auguste approached drycleaning establishments and asked to borrow or buy the liquid used to clean their customers’ clothes.

Rigoulot and Doriot covered one hundred twenty-five miles the first day. The following day they drove another one hundred miles without serious trouble. But while they were headed toward Brest, a problem in the differential delayed them twenty-four hours just outside of Morlaix. They had to make use of all their ingenuity in order to repair the damage, borrowing tools from the shoemaker of the hamlet and using a schoolyard offered up by a kindly teacher to repair the car.

That evening, after dark, “in the midst of the indescribable tumult of a curiously enthusiastic crowd,” the quadricycle arrived at Brest. The two men drove along the Rue de Siam, where they were greeted by M. Magnus, the Brest representative of Peugeot. After a night of rest, they set forth on their return voyage. The trip was filled with many comic moments that illustrated the radical and frightening nature of this new machine. Throughout the entire race, telegraphs alerted people of the advancing racers. In many villages, trumpeters sounded the approach of the rumbling vehicle. In one town, villagers “in strange and scanty garb” rushed out of their houses and inns to marvel at the oncoming vehicle.

“Thus it happened one Sunday morning, in Brittany, a worthy gentleman … surprised by the sound of the clarion just at the moment when he was changing his clothes, rushed out on the sidewalk holding his trousers in his hands, one leg in and one leg out of the trousers, while there came rushing out to stand beside him another curious individual from a barber shop, with the towel still at his neck, one half of his face shaved while soap suds covered the other half ! Moreover, as the dogs were not yet used to automobiles, they often bothered us the first days. Therefore, having found near Dreux a wagon whip, we took possession of it and when a dog disturbed us by jumping and running about us, we had only to raise the whip to get rid of him. This method, which should still be useful in many countries, rendered us a real service.”

Other onlookers were less amused. When Doriot and Rigoulet pulled into one village where people were going to church, “we saw women fall to their knees and [cross] themselves at our passing.” They thought the car was the sign of Satan.

The return to Paris was accomplished without any major problems. While there, they took “several Paris personalities interested in this new form of locomotion” for rides in their car. The two then returned to Valentigney without a hitch. All in all, it was a stunning success. Rigoulot and Doriot had covered fifteen hundred miles in 139 hours at an average speed of nine miles an hour without a serious accident other than the differential glitch. Instead of ruin, the Paris-Brest et Retour had made their reputations. That year, thanks to the race, Peugeot sold five cars, and boosted its output to twenty-nine cars the following year.

The year 1894 brought Peugeot and Auguste Doriot another level of fame. In July, Pierre Giffard and Le Petit Journal decided to hold the first race exclusively for automobiles. There would be no bicycles riding alongside Auguste this time—the car had earned the right to its own contest.

The contest was called the Paris-Rouen Trial of 1894 and was run from Paris to Rouen, a city about eighty miles northwest of the French capital. It was not truly a race but rather a point-to-point contest during which the reliability and performance of the vehicles were judged. The intrepid drivers competed without crash helmets, protective clothing, or barriers, racing over, as the great English driver Charles Jarrott put it, “the never-ending road that led to an unobtainable horizon.” The string of epic motor racing contests that subsequently took place prior to World War I were regarded with as much awe, excitement, and alarm as putting a man on the moon, and it all started with this 1894 contest.

The race organizers declared Auguste Doriot the winner. He had finished the course at an average speed of 11.5 miles per hour, slightly faster than the pace he set three years earlier. Doriot shared the seventy-thousand-franc purse with a car from Panhard-Levassor, which came in second. A famous picture taken after the race shows Auguste sitting in the car beside Giffard. Two other men sit across from them. A crowd of children and men surround the car, staring at the men and their bizarre contraption. Giffard and the two other men look back at the camera, smiling, while August looks straight ahead with a stern and focused expression, as if he was still surveying the road, racing toward that unobtainable horizon.

To Auguste, 1894 was a momentous year for a far more personal reason. While Auguste was living in Valentigney, he met a young woman named Berthe Camille Baehler. Berthe, known as Camille to her family, came from Voujeaucourt, another village in Franche-Comte, just east of Valentigney. Camille was born on August 16, 1870 to a Swiss father and French mother. Her father, Jean Baehler, came from Uetendorf, a Swiss village outside of Bern. Baehler supported his family through trading wood between Switzerland and France, and settled in Voujeaucourt, where he met his wife. Since Camille’s mother died when she was a child, she was raised by her grandmother and three older sisters.

A family photo taken when Camille was thirty-eight shows a fit, attractive woman with a heart-shaped face wearing a long white dress. In the photo, Camille tied her voluptuous mane of brown hair behind her head, which accentuated her short, straight nose, wide-set eyes, and pretty thin lips. Camille was advanced for her time. She spoke English and graduated from a French lycée, earning a living as a schoolteacher. Like Auguste, Camille was an adventurous spirit. Once, around 1890, she even traveled to Canada where she worked as a nurse and teacher for the children of a wealthy family in Montreal. Camille came back from Canada to marry Auguste, a marriage that was encouraged by their respective parents.

On September 27, 1894, Auguste and Camille were married in Valentigney. He was a relatively old thirty, while she was a fetching twenty-four. The couple shared a deep bond and created a loving home and atmosphere for their two children. After the wedding, Armand Peugeot sent Auguste to Paris to serve as the director of its factory and technical director of Peugeot’s first showroom on L’avenue de la Grande-Armée. Cars were so new that people did not know how to operate these machines, so Auguste taught customers how to drive, and took care of the repairs and maintenance of the growing fleet of Peugeot vehicles.

As a sign of his affection and loyalty to Auguste, Armand invited Auguste and Camille to live in a home owned by the Peugeots in the 17th arrondissement in the western part of Paris on 83 Boulevard Gouvion-Saint-Cyr. Mr. and Mrs. Armand Peugeot lived on the first floor, and Auguste and Camille took the second floor. Armand transformed the stable adjoining the house into a garage.

Later on, Georges would retell the many stories about his father and mother driving around Paris. “Peasants would chase them with whips, chickens would get killed, which made the peasants very mad,” recalled Georges. “One day Father was driving around Paris with Mother and her car got stuck. Well, they thought that they would be lynched, but somehow they finally convinced people and they saved themselves from a complete lynching. In other words, one could say that cars were not at all welcome. They are noisy, dangerous, and even horses didn’t like the cars. However, as more cars were made, as we know, all of that has changed.”