Читать книгу Creative Capital - Spencer E. Ante - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THREE COMING TO AMERICA

Оглавление(1921–1925)

ON JANUARY 4, 1921, when Georges Frederic Doriot stepped aboard the S.S. Touraine of the French Line, one of the grand old European steamships, he left France with two important items. In one pocket, he kept a letter of introduction to a gentleman named A. Lawrence Lowell, which had been given to him by a friend of his father who was an expert in technical education in France. In his other pocket, Georges carried a small French coin, a symbol of his father’s fortune, which had been destroyed by the war. The letter, which would radically change the course of Georges’s life, represented the bright light of the future; the coin embodied the dark weight of Doriot’s recent past.

“One of things that profoundly affected [Georges] was his father getting wiped out financially,” says James F. Morgan, a former executive of American Research and Development who became close to Doriot near the end of his life. “It affected his attitude toward risk. He was very, very cautious.”

At least Doriot knew where he was going, or so he thought. The same friend of Georges’s father who suggested he should come to America also recommended that Georges should attend the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). So Doriot and his parents contacted the American University Union and arrangements were made for Georges to attend MIT. Not knowing much, if anything, about America, the school seemed like a good choice. Established in 1861 in Boston, then the industrial center of the United States, MIT was a well-known regional engineering school that aspired to become a national research university.

As twenty-one-year-old Doriot cruised across the Atlantic Ocean at a steady pace of around 19 knots, he had more than a week on that beautiful ship to ponder his fate. La Touraine was built in 1890 by Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, one of the great French maritime companies. She was 522 feet long with two funnels and three tall masts, and held about fifteen hundred passengers. It must have been an exhilarating if not frightful journey. America was emerging as the world’s most powerful nation. And since the United States had escaped the Great War without any serious damage to her people, economy, or terrain, the opportunities offered by this vast country seemed limitless.

Up until the moment that he stepped on that ship, Georges’s parents had done all they could for their son. But he was now on his own, an inexperienced young man who had never left home for more than a few months, under immense pressure to do well in school so he could find a good job that would help him take care of his family. He had no family or friends in the United States, nor much money to fall back on. He was facing the most difficult challenge of his life. Standing on the deck of La Touraine, looking out into the deep dark void of the sea, Georges must have wondered: What does my future hold? What am I going to make of myself ? And what happens if I fail?

The S.S. Touraine pulled into New York Harbor on January 15 at noon. In the 1920s, New York’s harbor was as busy as Broadway during rush hour. Half of America’s exports and imports moved through the bustling piers that lined Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, and the New Jersey banks of the Hudson River. Oceangoing steamers entered or left the port about every twenty minutes. Doriot stepped off the boat, took in the armada of coastal freighters, harbor tugs, river steamers, and other ships bobbing in the water, and proceeded to the Hotel Pennsylvania across the street from Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Station.

One of the largest hotels in New York, Hotel Pennsylvania was built by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1919 and was operated by the successful hotelier Ellsworth Statler. Doriot checked into room 1721A. During his first night at the hotel, he was amazed by the double door that allowed men to put newspapers and packages in front of the second door, which he could then open from his room. It was a Sunday morning and in that space between the two doors Doriot was delighted to see several pounds of newspaper.

“I thought that, America being a very kind country, people realized that I had been at sea for a week and, therefore, had very nicely kept a week’s newspapers for me to read upon my arrival,” wrote Doriot. “Much to my amazement, I discovered that those pounds of papers were just the Sunday edition of the American newspaper.”

At one o’clock on January 20, Doriot hopped onto a train in Pennsylvania Station bound for Boston. He pulled into town just after six o’clock and checked into the Hotel Tremont. Soon after, he went to Cambridge to register at MIT. But before classes began, he decided to look up Mr. Lowell, the gentleman to whom his letter was addressed. “I decided that I should be considerate and polite, as my father and mother would have told me to be,” recalled Georges. “So, I looked for him and found that he was president of a university called Harvard.”

The Doriot clan had never heard of Harvard, though it was the most well-known and prestigious college in America. Georges called on Mr. A. Lawrence Lowell on the second floor of University Hall, with barely a clue as to the significance of the man. A well-known lawyer who was the son of one of Boston’s most prominent families, Lowell was president of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933, during which time the school flourished.

Albeit imposing, Lowell was kind to Doriot. When he asked the young man what he wanted to learn, Doriot shared his dream of one day running a factory. Lowell smiled at this response and informed Doriot that he had chosen the wrong school. Instead of MIT, he explained, Doriot should attend a place called the Harvard Business School, whereupon he took Doriot downstairs in University Hall and introduced him to Wallace B. Donham, the dean of the Business School. Having helped found the Business School over a decade earlier, Lowell remained an energetic advocate of the institution. Donham concurred with Lowell that Harvard Business School was the ideal place for Doriot, and without further ado, Georges’s papers were transferred over to Harvard.

Placing his trust in these wise men, Doriot enrolled at Harvard Business School in the spring of 1921. Doriot was the first Frenchman to attend the school, and one of only a handful of foreign students, the others hailing from the Philippines, Greece, and China. He studied the basics of business education: industrial management, factory problems and systems, accounting, labor relations, statistics, and corporate finance. He enjoyed the experience very much and was impressed by his teachers. As part of his course in factory systems, Doriot took a few field trips, including a visit to the Rolls Royce factory in Springfield, Massachusetts, during which he inspected the plant and reviewed its cost accounting system.

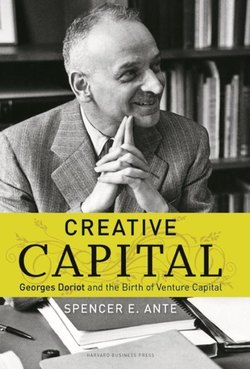

A photograph taken in March of 1921 that Doriot sent to his parents revealed that Georges had matured considerably since his days in the Army. The soft, timid face of a teenager had hardened into a portrait of a serious young man with penetrating blue eyes and a short, trimmed moustache. The military dress was replaced by the armor of an enterprising young businessman: a sharp, three-piece suit, crisp white shirt, and well-knotted tie, accented by a white handkerchief peeking out of his suit pocket. These years gave birth to the formal look that Doriot favored until the last years of his life, always wearing suit and tie in public.

During his second semester, Doriot was listed as a “special student” in the Official Register of Harvard University, along with thirty-seven other young men. In those early days of business education, an MBA degree was a brandnew concept and had yet to acquire the cache it has today. So many students, including Doriot, only took the basic core curriculum of the first year, and then left to seek their fortune.

Near the end of 1921, Doriot met some financiers in New York from the well-known investment bank Kuhn, Loeb & Company. They offered him a job, which he gratefully accepted. Comforted by the security that came with such a position, Georges decided to settle down in America. During an earlier trip back home to France, he had discussed the decision with his parents. “I had come to France to visit the family and they decided that it was probably best for me to stay in the United States because people there were very nice to me and I could probably earn a living,” recalled Georges. “Things were not very happy in France at that time. We were still suffering from the after-effects of World War I.”

Things were very happy in New York City, though. When Doriot walked around New York over the next few years, he marveled at a city on the cusp of greatness, a city of immense vitality, of great “stone buildings that the human mind has not had the vision to conceive nor the power to build until New York stimulated mankind with its magic,” as Rebecca West described it. It was the time of great dance halls, where throngs of city dwellers crammed into hundreds of joints, drank moonshine, took in cabaret shows, and danced the night away.

These were the sights and sounds Doriot saw as he walked to and from his office in Lower Manhattan. His position at the bank was a cautious yet smart choice for a first job. Founded in 1867 by Abraham Kuhn and Solomon Loeb, two German-born brothers-in-law who had run a successful merchandising business in Cincinnati, Kuhn, Loeb moved to New York to take advantage of the nation’s economic expansion. In the late nineteenth century, Kuhn, Loeb made its name by selling securities for many of the early railroads. Kuhn, Loeb was the only Jewish banking house that had the temerity to challenge Morgan in the big money game of financing railways and governments. While the House of Morgan focused on railroads east of the Mississippi, Kuhn, Loeb mostly targeted railways in the south and west, including the Chicago and North Western Railway, Norfolk and Western, and the Southern Pacific.

Kuhn, Loeb was also in the vanguard of international finance. It tapped European capital to fund the railroads, made the initial dollar placements in the American market for leading European firms such as Royal Dutch Petroleum, and helped Japan defeat Russia in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and 1905 by loaning Japan $200 million. During World War I the firm aided the Allied cause by making a series of crucial loans to the cities of Paris, Bordeaux, Lyons, and Marseille, which used most of the proceeds to prop up the finances of the French Government.

Under Jacob Schiff, the senior partner who led the firm until the early twentieth century, Kuhn, Loeb came to rival J. P. Morgan & Company as the leading investment bank in America. Schiff was instrumental in pushing the bank to finance industrial enterprises. While the traditional investment banks of Morgan and Brown Brothers Harriman underwrote shares for blue chip companies such as U.S. Steel and General Electric, Kuhn, Loeb and other German-Jewish bankers such as Lehman Brothers and Goldman Sachs brokered securities for companies that were spurned by gentile firms as too lowly—retail stores and textile manufacturers. Among them were Sears, Roebuck, R. H. Macy, and Gimbel Brothers. Beginning in the 1890s, Kuhn, Loeb helped to secure loans for a number of pioneering enterprises such as Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, Western Union Telegraph Company, and the United States Rubber Company. “Let the Jews have that one,” was a familiar refrain on Wall Street.

Even though Kuhn, Loeb and other Jewish banks expanded the reach of financial markets, they were not in the business of betting their own capital on new enterprises. These banks were mostly middlemen, restricting their activities to selling government bonds or the securities and bonds of large, established companies to pools of investors that they rounded up—a safe though still lucrative business.

The House of Morgan, by contrast, remained even more conservative. It sometimes took small stakes in the companies for which it raised money as a commission. But it did not broker stocks, only underwriting railroad bonds, government bonds, or corporate bonds of the biggest firms such as U.S. Steel, General Electric, General Motors, and AT&T.

Young, unproven companies were still the stepchildren of capital markets, overlooked and neglected. That left entrepreneurs with the same old miniscule set of options: raising money from friends, family, or rich individuals. The only other financing option for new enterprises was to merge. By combining their financial resources, several small companies could increase the pool of capital that was necessary to help grow their businesses. Mergers could also raise the financial profile and health of a firm to a level where it could secure debt financing.

This was exactly the case with one of America’s oldest and most prestigious technology companies: IBM. In 1911, the Computing Tabulating Recording Corporation, the predecessor company of IBM, was formed through the merger of three separate firms: the Tabulating Machine Company, the Computing Scale Corporation, and the International Time Recording Company. The combined companies manufactured a wide range of products, including employee time-keeping systems, meat slicers, scales, and, most importantly, punch card machine technology—an innovation which ultimately led to the development of the computer. The three companies were brought together by financier Charles Flint, who helped the firm raise a $6.5 million bond offering.

According to existing records, Georges Doriot did not actually work for Kuhn, Loeb, but rather for a closely affiliated firm named New York & Foreign Development Corporation. In fact, Kuhn, Loeb and the New York & Foreign Development both shared the same address in lower Manhattan: 52 William Street. Although Doriot would only work for the company for four years and the period is barely mentioned in discussions of his life, his time here was significant in several ways.

In working for a Kuhn, Loeb affiliate, Doriot entered the rarified atmosphere of high finance, receiving his indoctrination into the world of power. He learned how to behave around power, how to be comfortable in a world of hidden influence. The connections he made at Kuhn, Loeb would serve him well the rest of his life. Doriot also received first-rate training in the craft of finance and investment banking, and gained an appreciation for the importance of technology. In fact, Doriot’s main job was to help evaluate new technologies for possible investment. His ability to judge men and their ideas, which were formed during these early years, would remain a signature talent throughout his life.

One of the more fascinating characters that Doriot befriended during this time was Sir William George Eden Wiseman, the president of New York & Foreign Development. A descendant of English royalty, Wiseman worked as a banker at Herndon’s in London before World War I. During the war, he served in the infantry, later coming to the United States as chief of the British Military Intelligence. After the war ended, he acted as a liaison between the British government and President Woodrow Wilson, and then became an advisor at the Paris Peace Conference. Following the peace accords, Wiseman, along with several other fledgling diplomats, joined Kuhn, Loeb.

More significant was Doriot’s relationship with Lewis L. Strauss—another statesmen-cum-banker who joined Kuhn, Loeb after the war. Over the next thirty years, Doriot and Strauss would become the best of friends. Doriot, eager to form new ties as an unmoored immigrant, became so attached to Strauss and his wife Alice that he considered them part of his family just a few years after striking up a friendship. For a newcomer trying to make his way in a foreign land, Strauss’s Horatio Alger tale must have struck a chord with Doriot.

The son of a Jewish shoe salesmen from Virginia, Strauss rose above his meager beginnings to become a rich investment banker and chairman of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission. Valedictorian of his high school class, Strauss was offered a scholarship to the University of Virginia but turned it down to sell shoes for his father’s struggling business. Strauss later saved up $20,000 to pay for college, but guided by his mother’s desire for her son to serve the nation during war, Strauss instead miraculously landed a job as private secretary to the industrialist-turned-statesman Herbert Hoover.

President Woodrow Wilson picked Hoover to take charge of the Food Administration, which provided a steady supply of food to the American and Allied Armies. While in Europe, Strauss distinguished himself by helping Hoover direct America’s post-war relief effort, and by coming to the aid of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which alleviated the suffering of thousands of oppressed European Jews. Strauss parlayed his relief work into a job offer from the partners of Kuhn, Loeb, many of whom were Jewish and impressed by the way he helped move emergency supplies to Jews living in Vienna, Warsaw, Prague, and the surrounding war-torn areas.

Doriot came to know Strauss because he was a director at New York & Foreign Development. In Doriot, Strauss saw a younger version of himself: a young, smart man full of energy, brio, and a desire to make his mark on the world. The two worked together on a deal in the fall of 1923. On September 24, 1923, members of Kuhn, Loeb organized an entity called the International Gear Company, Incorporated to investigate an innovative new method of commercial gear production known as the Anderson Rolled Gear process. The process of forging gears under heavy heated pressure in a rolling action was “unquestionably the outstanding achievement in modern methods, for not only is a much lower cost of production realized, but the gears produced are stronger, tougher, and more accurately formed than the best types of gears produced by the machining processes of this generation,” according to the leading machine experts of the day. Even though he had turned only twenty-four on the very day the company was incorporated, Doriot was elected as one of seven directors of International Gear. It would be the first of many directorships for Doriot, who learned much about the world of business through his participation on the boards of dozens of companies.

In the spring of 1924, Strauss asked Doriot to compile a list of French industrial firms, along with their financial backers. On March 18, Doriot wrote a letter to Strauss describing his findings. The letter illustrates Doriot’s emerging iconoclasm and his penchant for holding strong opinions that he wasn’t afraid to share, especially opinions about his native land. In his analysis of the links between French banks and industrial firms, Doriot informed Strauss “there is no definite connection, and when there is a connection it is very often a useless one. My experience has been that from the standpoint of a Company, it is perfectly useless to do business with the Bank of France.” Over the years, long after Doriot left New York & Foreign Development, Strauss continued to turn to Doriot for his expertise in evaluating new technologies and investment opportunities.

In the fall of 1924, Doriot tried his hand at something entirely new: writing for the public. Doriot never took writing seriously but his efforts signaled the beginning of his evolution into a public figure, offering pointed commentaries on the world’s most important issues. Under a one-word pseudonym, Beaulieu, a cheeky reference to the village near his home in France, Doriot wrote two contrarian essays for The New Republic criticizing the Dawes Plan, an agreement designed to keep the lid on growing post-war tensions in Europe. After Germany defaulted on its steep reparations payments of nearly twenty billion marks in the summer and fall of 1922, the French and Belgian governments occupied the Ruhr region. The occupation of the center of the German coal and steel industries both outraged Germany and put further strain on its economy.

To defuse tensions and get Germany back on a payment plan, the Allied Reparations Committee asked the businessman and politician Charles G. Dawes, who soon after became vice president to Calvin Coolidge, to find a solution. After a long and difficult negotiation, Dawes unveiled his plan in April of 1924. It called for a reparations schedule of one billion gold marks in the first year, rising to DM2.5 billion in the fifth, providing some room for changes if the price of gold went up or down more than 10 percent.

In Doriot’s first story, “The Dawes Plan Myth,” published in the September 24, 1924 issue of The New Republic, he argued that the plan “is mainly and primarily a myth” because it was an unrealistic intrusion into Germany’s affairs. “The plan does provide for an initial truce,” wrote Doriot. “That is all to the good. It holds out the hope of reparations payments. That approaches fraud. As will appear, no substantial reparations can be paid under it.”

In the second essay, “The Dawes Plan and the Peace of Europe,” published in the December 10, 1924 issue, Doriot stepped up his attacks. No longer would reparations be paid, but now Doriot argued that “the administration of the plan in accordance with the concept of its framers constitutes a standing threat to the peace of Europe.” The reason? He believed that high reparations payments would come from the hide of the German “workman and consumer which must in time lead to an anti-Allied outbreak.”

Doriot was ultimately right, but his analysis was too premature for anyone to notice it. In fact, the Dawes Plan initially succeeded beyond expectations, leading to a wave of foreign loans that gave Germany enough money to pay reparations to France and Britain until 1929. The plan also helped keep the peace in Europe, as war did not break out again until Hitler invaded Poland in 1939.

Doriot’s use of a pseudonym betrayed a deep-seated fear: he hated writing. It is a strange admission, revealed years later in his personal notes, from someone who became a professor and was actually a very good writer, a tireless composer of thousands of pages of prose that was clear as a windowpane. The confession underscored Doriot’s lack of self-confidence, which dogged him throughout his twenties as he struggled to find his way. “I never liked writing,” he confessed. “I do not do it well. My sentences do not “sound” well. Also, I never thought that I had anything to say that had lasting characteristics or value, nor would it have any interest for other people. When I had to make a speech (which I never enjoyed), I always asked for no publicity. The speech was designed for a particular audience and had no value for others.”

The two New Republic stories were an interesting diversion from Doriot’s time at New York & Foreign Development. Back at the firm, Doriot was earning a reputation as a savvy, hard-nosed evaluator of investment opportunities. In one instance, in the winter of 1925 Doriot helped investigate and broker a deal for a new ice-making machine with the American Radiator Company. “There is no doubt as to the fact that the outside arm can make any amount of ice that you may wish, and this is in much shorter time than ordinary machines on the market,” wrote Doriot to R. R. Santini, the head of American Radiator, after seeing a demonstration of the machine. The following year, at Sir William’s request, Doriot visited the Prince George Hotel, north of New York’s Madison Square Park, to investigate an invention made by a Mr. de Northall, who was demonstrating a model saw in an apartment in the hotel. In a subsequent memo, Doriot revealed a talent for cutting to the heart of a matter.

“I found that Mr. de Northall had contracted very heavy debts and owed money to friends and his relatives. It then became apparent that unless a certain sum of money could be set aside to take care of Mr. de Northall’s indebtedness, it would not be possible at the time, to spend anything merely on the development of the invention. Sir William Wiseman and his friend, being bankers, and not promoters of doubtful enterprises, also not being primarily interested in the lumber industry, I did not hesitate to recommend Sir William to state that he was not interested.”

Then Doriot ripped into the saw, displaying his razor-sharp analytical skills. Inspecting the machine in the hotel room, Doriot found that it was not in working condition, and that the inventor had no idea how much power the saw needed, nor did he have a clue as to the cost of its installation. “There were several other mechanical difficulties which I pointed out to Mr. de Northall,” wrote Doriot. “I would not have advised anybody unfamiliar with the lumber industry to spend any time or money on that invention.”

Doriot demonstrated an ability to make more subtle judgments as well. One of the more unusual projects that Doriot was asked to evaluate was an Ecuadorian natural resources venture. The plan, which forecast a very high rate of return, was to cut exotic trees in the mountains of Ecuador and then float the wood down to the coast, where a mill on the shore would then transform the logs into furniture veneer. Doriot told the bankers that when he was young boy in France he learned that some wood, being heavier than water, did not float. The bankers quickly discovered that the wood they wanted to float down the river sunk like a stone. New York & Foreign Development never invested in the program. “He had a very candid and open-minded approach to all of the problems,” says Doriot’s close friend Arnaud de Vitry. “Great businessmen on Wall Street missed this factor in their analysis.”

In the future, Doriot’s boldness, powers of judgment, and technical fluency would help him pioneer the venture industry. Before he was able to step up to that level, though, he had to answer some of the more basic questions of his young life. True, he had found a home in America. But he was still without a career, a soul mate, or any guiding purpose.