Читать книгу Global Warming and Other Bollocks - Stanley Feldman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

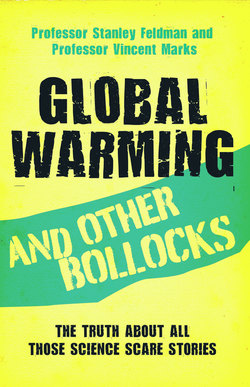

This book

ОглавлениеThis book is about evidence. It challenges some of the assumptions that we have come to accept as fact. It presents evidence that either supports the hypothesis or indicates that it is not necessarily the only, or even the best, explanation of observed events. In some instances, even the best analysis of present dogmas is unable to answer concerns about future uncertainties. Austin Williams points out in this book how mankind has, in the past, survived by overcoming the problems posed by nature while the doomsday soothsayers advocate a retreat into a primitive world of doing less, having less and achieving less. On the other hand, few would question the view put forward by Vincent Marks, in his chapter on population, that there must ultimately be a limit to unbridled population growth and consumption. However, no one knows what that limit is or how it will be affected by new technology and by world events.

We live in an uncertain and unpredictable world – but none of us enjoys uncertainty. Nevertheless, we have to make decisions, and do so on the ‘balance of probabilities’ when we know what the alternatives are. Some scares, such as the probability that we will suffer a human bird flu pandemic sometime in the future, are justified by scientific evidence; some, such as the effect of unlimited growth, depend upon unpredictable future developments; while yet others are patently wrong. The millennium-bug scare was groundless. So were prophecies that AIDS and new-variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) would decimate the population. Similarly, the prediction, made in the 1970s, of the coming of a new ice age and the authoritative forecast in 2006 that rainfall in England would decrease to a point where drought would be usual. All were pronouncements that made headline news but all have proved to be wrong.

The paradox that many of the world’s great scientists are or were (religious) believers will not have escaped our readers’ attention. The ability to accommodate a belief system at the same time as a rigorous scientific inquisitiveness, in the same brain, is far from rare. Few things in life are certain beyond having a beginning and an end – and some even question this.

In our present society, government bodies and authorities increasingly make decisions for us about the kind of life we live. It is essential, therefore, that their recommendations are based on sound evidence. Too often they are the result of an ill-conceived overreaction to pressure by special-interest groups, a media campaign or zealots presenting their beliefs in the guise of fact. As a result, the way we live, what we eat, what we do and how we spend our money is often based on a doubtful dogma that originates from often well-meaning government circles. This can be dangerous, as it undermines the influence of credible government warnings and advice, such as the benefits of using seat belts in cars, and dangers of drinking excessively or of smoking.

Good advice is helpful and should be welcomed, but it must be based on evidence and not on questionable dogma. It should be permissible for governments to admit that the evidence upon which they have to base policy is at the civil rather than criminal level of certainty and often not even as good as that.