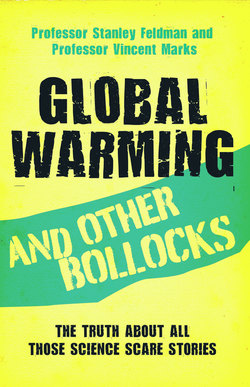

Читать книгу Global Warming and Other Bollocks - Stanley Feldman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеSTANLEY FELDMAN

Knowledge may be expensive but it is much cheaper than ignorance.

The pragmatist says, ‘I change my mind when the facts change.’ The dogmatist says, ‘My mind is made up – do not confuse me with facts’.

NEWSPAPERS, magazines, television and radio are constantly bombarding us with stories presented as facts. Unfortunately, many of them turn out to be opinion rather than something that has been proven to be likely or correct. The problem we face is how to distinguish between a belief or an opinion, and a fact.

In the courts of law it is the accumulation of evidence that helps to prove a proposition ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ in criminal cases, or, in the civil courts, the lower standard of proof, ‘on the balance of probabilities’. In the world of science the same criteria should hold true. It requires good, reliable evidence to substantiate a hypothesis. All too often the stories that reach the media fall far short of the level of proof required by the criminal courts and seldom even reach that required by the civil courts. Without corroboration all information is uncertain and exists in a twilight world of half-truths and make-believe.

In his book The Devil’s Chaplain, Richard Dawkins, the professor of public understanding of science at Oxford University, wrote a letter to his daughter in which he says that it is his greatest wish that when she is grown up and is told that something is a fact she should ask herself, ‘Is this a thing people know because of evidence?’

Dawkins wanted to impress upon his daughter the importance of distinguishing between dogma – or firmly held belief – and verifiable fact. Unfortunately, it is often more comfortable not to try to make the distinction but to ‘go with the herd’ and unquestionably accept what one is told because it is believed by so many seemingly rational and knowing people. As the author Michael Crichton pointed out, science is based on evidence and proof – not popular opinion or ‘consensus’.

Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with the consensus. There is no such thing as consensus science. If it’s consensus, it isn’t science. If it’s science, it isn’t consensus. Period.

Accepting a belief as a fact, without convincing evidence, is the way to become a member of an unthinking society of anti-intellectual zombies. Throughout the history of civilisation, many ideas that were previously held as certainties, supported by belief and experience, have been found wanting in the light of new information. Newtonian mathematics, which formed the basis of so much of our teaching, has been found to be only half true by the modern theories of quantum mechanics.

Our knowledge of the universe has been demonstrated to be based on inadequate concepts that were taken as fact before the theory of relativity and the present means of exploring space had shown their limitations. Until recently we were told, with absolute certainty, that foods rich in cholesterol caused heart disease. This is now known to be wrong. We are constantly developing new ways of testing and evaluating evidence that is causing us to question previously accepted dogma. This is the basis of knowledge; it is the way of science.

To meet these uncertainties we need to scrutinise beliefs and examine past evidence in the light of new knowledge. It is by experimental evidence and by reason that we distinguish between dogma and fact. Just as the availability of new methodologies, such as DNA typing in criminal investigations, has led to examination of past convictions, and space exploration has shed new light on the origin of the planets, so new research will invariably cause us to challenge more and more present ‘certainties’. If further research casts doubt on the original propositions, it must be categorised as a hypothesis, not as fact. If the new evidence – provided it can be substantiated – is incompatible the hypothesis must be abandoned. To persist in maintaining doubtful dogma in the face of evidence, puts it in the realm of an unsubstantiated ‘belief’ or myth.

In this book we have looked at some commonly held beliefs – dogmas that countenance no challenge either because they are taken for granted by those in authority or they have the seal of, so-called, ‘scientific approval’. While it is often more comfortable to accept some of these dogmas – indeed to challenge them one runs the risk of being labelled an iconoclast – it is our duty to encourage debate, however certain we are of our own correctness. It is necessary to examine all of the evidence constructively to find out how much supports and how much contradicts a particular proposition or hypothesis. For there to be confidence in a hypothesis it is essential that any evidence that questions the validity of its assumption be answered. When they are, it can be dignified by its description as a theory.