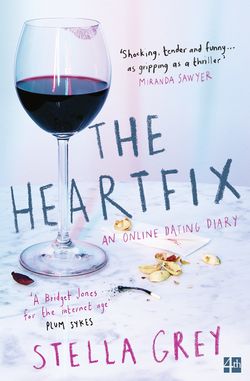

Читать книгу The Heartfix: An Online Dating Diary - Stella Grey - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеThe end of my marriage was an event that came suddenly and unexpectedly. It was rather like that scene in Alien, in which John Hurt is sitting contentedly eating spaghetti with the spacecraft crew, and then the infant monster bursts out of his chest, leaving everybody shocked and splattered. My ex-husband fell in love with someone else, and that’s that. I can say, ‘And that’s that,’ now, but I’m not going to pretend it didn’t take time and a lot of ups and downs to get here, to the point at which I’m able to use three words. At the time it didn’t feel real; we’d been married a long time; and then, when I started online dating, hoping to be cheered up, things became even more surreal. Life got quite Alice in Wonderland, as you will see. The journey I took – and I do think of it as a journey – was weird, hilarious, difficult, mind-boggling, nerve-racking and ultimately … (but I’m not going to spoil it for you). I online-dated for almost two years, and it isn’t an exaggeration to say that it shaped the person I am now, a different person in various ways to the person I was. In many ways I like her better than the old me.

Dating was a strong medicine taken in the hopes of softening the corners of a desperate sadness. It wasn’t easy, drawing the line that ended the married years and declaring myself to be single. It wasn’t that I bypassed the heavy drinking phase. When somebody announces that they’re leaving you, it’s a physical shock. It starts in your brain and reverberates through your bones. It might feel like being told you have a terminal illness (when in fact it’s usually highly treatable, and in time you’ll get better). First there is denial, and then there is rage, and then there is acceptance. Denial is parasitical and tries to colonise you, and the rage that follows is like a baby cuckoo, perpetually hungry, and then there’s acceptance, when you begin to want to make the best of getting up in the morning and carrying on. Renewal might follow. Renewal is a painful experience. It means being properly alive again, and trusting and vulnerable, and that can hurt.

There came a point, having healed sufficiently, having moved on from the daytime vodka phase – daytime vodka while eating whole tubs of ice cream and crying over property search programmes (it’s distressing to be a cliché, but there you are) – at which I thought, So now what? So now what? is a good sign. It marks the first day of looking forward, and not back. I’m not saying I stopped harking back, but I began to look ahead and think about what might happen next. I’d always imagined the future would be shared with my husband, and now there were many other roads, forking off, over hill and dale and into the unknown. It occurred to me for the first time that I might not be unhappy for the rest of my life. I realised that it was all in my hands. I ditched the vodka, the dairy products stacked in the freezer and daytime television. I had a haircut and colour, bought a dress and went to the bookshop. I sat on a park bench with my books in a bag (not all of them self-help, either), tilting my face up to the early spring sunshine, and decided that I needed to meet new people, and by people I mean men.

The world was full of couples and I wanted to be half of one of them. That was the mission. It was my own diagnosis of what I needed. I was heartbroken and needed a fix. I needed a heartfix. The world was full of couples busy being casually happy with one another. The young ones didn’t trouble me, the kind who canoodled in cinema queues. But the midlife ones really bothered me, and particularly the silver-haired, affluent couples holding hands in the street. There was a prime example in the coffee shop where I used to hang out at the weekend, a pair who were just back from holiday. They were talking about how much they were missing island light and their swimming pool. She was wearing the bracelet he’d bought her, and it was turquoise against her tanned arm. The non-affluent retired bothered me too: the world was full of ordinary untanned, badly dressed, unattractive older couples who had every intention of being together till they died, and I began to find that simple loyalty overpoweringly moving. Heartbreak felt constantly hormonal, like persistent PMS. I was having trouble feeling sensible about the odds of finding somebody who would feel as natural and right at my side as my husband once had. But I needed to do something, even if it turned out just to be a phase on the way to being happy to live on my own.

A friend suggested internet dating. She’d plunged in and she had found someone lovely. Most people in the online pool were dull or odd or nuts, or love rats, she said (I assumed she was exaggerating), but it was a lot more fun than endless nights in with slippers and shiraz and Sudoku, and only a dog to talk to. Online dating! It wasn’t for me. I wasn’t an online dating type of person: that much I was sure of. I’d read the horror stories that circulate, and had heard some too, about cattle markets, players and lotharios, married men and psychos and scams. But it seemed daft not to look, so I hovered around the sites for a week or so. (It was ‘free to join!’– though not to reply to messages, it turned out, when I’d taken this promise at face value.) I spent time dipping in as a lurker and observer, equal parts horrified and tantalised. Being tantalised was surprising. There were male profiles that intrigued me: kind-faced, rumpled, witty men who’d managed to hurdle over the dignity issue involved in self-advertising, and had signed up. Once I’d done the same, I had a powerful sense of being part of something. It was strangely poignant, this feeling, as if I were part of a great river of people who had been bashed by life and were brave. They were bold enough to embark on the search for love in this new-fangled digital way, each risking humiliation, failure and ridicule in their determination to swim upstream. I was aware of the distinct possibility of all three outcomes – humiliation, failure, ridicule – but I was lonely, and I don’t just mean for male company. I was lonely in general; unhappiness is a solitary state and I couldn’t keep talking about it and going round in circles in my head and feeling stuck. I needed to break out of the cycle, and be fresh, to have a fresh life. The bizarre process of choosing potential lovers and life-mates from what is essentially an online catalogue would bring a broadening-out into my narrowing life, at least, and I was badly in need of something radical. Distraction, at the least. Was a second love possible? Was a second love found via a website for singles remotely possible? It seemed unlikely. But what else was I going to do – sit here festering, eating snacks and watching Miss Marple reruns?

So I decided to have a go. What did I have to lose, after all? I signed up to the biggest of the no-fee sites, filled in the questionnaire, posted a photograph that hinted at hidden depth, and took two hours to write and polish my profile, distilling life experience and interests into nuggets that offered fascinating glimpses of my inner world (I thought). Gratifyingly, half an hour later I had two messages. The first said: ‘Hello sexy. You look very squeezable. First, can I ask – do you eat meat? I couldn’t kiss someone who consumes the flesh of tortured animals.’ The second said: ‘Hi. I can see from your face that you have shadows in your heart. I think I can help.’ I hit the reply button and asked how he was going to do that. ‘I will shine a great light upon you,’ he wrote. I logged off and sat for a while, staring at the screen. Then I logged on again, to see if anyone else had written yet. There was a message from someone called Freddie. All it said was ‘Hi’ followed by nine kisses. I had a look at Freddie’s profile. It consisted of two sentences: ‘Honest, caring, tactile man, looking for sensual woman. Please – no game players, gold diggers, liars or cheats.’

I reckoned that what I needed was more sites and more variety, so I signed up to every worthwhile-looking one I could find and afford, a total of nine. (As time went on I whittled this down to four, with occasional forays into a fifth and sixth; and then, in the second phase, somewhat desperately, I added another eight.) It was quite an expensive endeavour. Online dating is big business and it’s easy to see why. Basically it’s money for old rope. If you build it, they will come: create a search engine and a messaging system, then stand back and let people find one another. It’s a great big dance hall, though without the dancing, or the band. Or the hall. Generally what you’re paying for is access to their database, though some sites claim to work hard on your behalf by matching people ‘scientifically’ via hundreds of questions (this didn’t work for me, as you will see).

I decided that I was going to have to be pro-active and start some conversations, rather than sitting waiting for men to come to me. In general, men were not coming to me. I’d launched myself into the scene expecting to make some kind of an impression, but made very little impact. It was like bursting into a party dressed to the nines, ready armed with funny stories, and saying, ‘TA DAAA!’ and having almost everybody ignore you (other than the people asking everybody for naked pictures and hook-ups. I didn’t count them in my success rate). Something had to be done to kick-start the process, so I began to take the initiative. I started with men in my own city, of about the same age, education and outlook. This didn’t go well. The last thing most divorced men appeared to be looking for was women of the same age, education and outlook. You may protest that this is a wild generalisation and is unfair. I can only tell you of my own experience, which is that they have high expectations, a situation exacerbated by being heavily outnumbered by women. But I didn’t know this then. I was like a Labrador let off its lead at the park, bounding up to people expecting to make friends. A chatty introduction email went off to a dozen candidates who lived within a five-mile radius. When there were no replies, I thought something must be wrong with the message system. Then I found that one of the non-repliers had removed the three items from his likes and dislikes list that I’d mentioned I also liked. Withnail & I, dark chocolate, rowing boats: all had been deleted. Another of the men had blocked me so I couldn’t write to him again. This, I have to tell you, stung me deeply. It winded me. I hadn’t realised online dating was like this.

After the initial sting, I had the first experience of certainty. I was sure that I’d found him, the man for me. Graham had a lovable face and an attractive sort of gravitas (he was a senior civil servant). He wrote well, and lived a mere five miles away. His profile echoed my own, in the things he said, believed, wanted. We were 100 per cent compatible. Being a novice, I was sure he would see me in the same way. I thought, This is it; I’ve done it; here he is. It was an obvious match! I wrote him a long message about myself, a letter, picking up points of similarity and initiating what I was confident would be lively conversation. I was almost debilitated by excitement. It was the beginning of something wonderful, of that I was sure. But I was wrong, completely wrong. It wasn’t the beginning of anything. Graham didn’t even reply. Not realising that ignoring compatible people who’d taken the trouble to write a letter of many paragraphs might even be an option (people did that?), I checked my inbox over and over for the following forty-eight hours. It seemed clear that the only possible reasons his enthusiastic response had been delayed were that he was a) away, or b) too crazy-busy to write his rapturous reply. But that wasn’t it. Graham had read my message and dismissed it. I never heard from him, not a word – though he came and had a look at me. Twice. He looked at my profile page, at what I said about myself and at my picture, and then he looked again, and then he decided to ignore me. So this was the first thing I learned: men I had an instant attraction to, and who sounded like thoroughly decent people, could actually be arseholes. That was Lesson One.

Because I had more or less talked myself into being horribly smitten, and because I’d given so much of myself in my lengthy approach letter, Graham’s decision not even to answer my email hit me hard. I’d been judged unworthy of a reply. It was a powerful first hint that in this context, essentially I might be thought to be a commodity, one not much in demand at that. I felt hurt. I had feelings. This unreal situation was prompting real emotions, ones I didn’t want to have. One of the problems with online dating is that it facilitates those who want to dehumanise the process just as much as it facilitates the romantic and genuine. The system, like any other, is a hard cold thing. People can take refuge in that, in the machine, in the distancing and anonymising that’s built in to protect them. But they can also exploit it. My own response to these initial hard knocks was that I began to expect a lot less. I wrote shorter approach messages, while still taking trouble to personalise them: ‘Hello there, I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed reading your profile, and also to say, the book you say you never tire of is the book I never tire of too. Have you read the sequel?’ The recipient didn’t reply. Ever.

It wasn’t only the way people behaved on dating sites that astounded me, but also the descriptions some gave of themselves there. Perhaps it’s social media’s fault that lots of men have embraced the power of the inspirational quote. Sometimes these are attached to names at every sign-off (Gary ‘Love life and grasp and hold on to it every day xxx’). Some had profiles that I suspect were drafted by their 14-year-old sisters. ‘My favourite things are the crinkle of the leaves under my shoes in autumn and birdsong after the rain.’ ‘I don’t care about beauty,’ another had written. ‘As long as you have a beautiful soul I want to hear from you.’ I was charmed. I wrote to tell him I was charmed. He didn’t reply; perhaps what he wanted was inner beauty attached to a 30-year-old body. Another early correspondent was enraged about my preference for tall men. He wrote me a one-line message: ‘Your insistence on dating men over 6 feet tall is heightist.’

I explained that I am taller than that in shoes. ‘I’m a tall woman,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry if you have an equal-opportunities-oriented approach to sex, but I like to look up to a man when I kiss him. I continue to allow myself that preference. Apologies if that offends.’

‘You know the average height of men in the UK is 5'10 don’t you,’ he replied. That happened to be his own height.

‘Luckily I’m not interested in averages,’ I wrote.

‘You may as well ask for an albino who’s a billionaire,’ he countered.

It was hard to know how to reply to that, so I didn’t. I always replied to a first approach, unless there was something vile about it, but didn’t feel obliged to keep responding to people who replied to my reply, and especially not those I’d said no thank you to. Otherwise some pointless conversations would never have ended.

I paused at the smiling face of a man called Dave who lived in Kent. ‘Hi I’m Dave, an ordinary bloke, 43 years old and ready for a serious relationship.’ What caught my eye was that Dave was 52. The age updated automatically on the heading of the page, though he hadn’t updated the personal statement that appeared beneath it. His description had been written a full nine years ago. ‘Oh God,’ I said aloud. ‘Dave’s been here for nine years!’ Poor Dave. ‘I hope you find someone soon, Dave,’ I said to the screen. ‘Unless you’re a bad man, obviously, in which case womankind has made its judgement and you should probably take the hint.’

Most people’s dating site profiles say little about them. Some real-world interesting people have no gift for self-description and fall back on the generic; some people are careful to be bland and unspecific; and others are actually as dull as their blurb suggests. It can be tricky to deduce which of the three you’re dealing with, at first or even second glance. There are those who appear to say a lot, but actually give nothing away. Everybody loves holidays and music and films and food, and wants to travel the world. Everyone has a good sense of humour, works hard and likes country weekends; everybody loves a sofa, a DVD and a bottle of wine. Then there’s the problem of integrity. Some things that are said might prove not to be true: marital status for example, or age, or location, or general intentions (or height). ‘I’m looking for my soulmate,’ doesn’t always mean exactly that. Sometimes it decodes as I’m not looking for my soulmate, but that’s what chicks want to hear. Inside the anonymity of the database, nothing can be relied on at face value. I’m not suggesting there are grounds for constant paranoia, but I learned to be on the alert. In the early days I had a conversation with a professor at a certain university, and checked the campus website and found that he wasn’t. When I challenged him his dating profile disappeared and my emails weren’t any longer answered. When I told a friend – who was also searching for someone – about this, she said, ‘Sometimes I’m confident, and sometimes taking on a second-hand man is like going to the dog refuge and picking a stray, not knowing what its real history is or how it might react under pressure.’

Not that this is everyone’s experience of online romance. I know of dating site marriages … well, I know of one. Admittedly the woman in question is a goddess. The goddesses, the willowy ones with the cheekbones and the swishy hair, are probably swamped with offers. As for me, all the dating site gods (tall, articulate, successful, well-travelled; they don’t even have to be handsome) were swishing right past me.

I asked my friend Jack for a male appraisal of my dating site profile. He said it was lovely, like me. That was worrying. I needed clarification.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘You expect a lot. You make it clear you only want clever, funny, high-achieving men.’

‘I don’t say high-achieving. I don’t say that anywhere.’

‘You say it without saying it. And it’s clear that you’re alpha. That puts men off. I’m just saying.’

‘So what should I do? Claim to be a flight attendant with a love of seamed stockings?’

‘That would get you a lot of attention. But then you’d need to follow through.’

‘I’d have to study the British Airways routes and talk about layovers.’

‘Every middle-aged man in the world dreams of layovers,’ Jack said, looking wistful.

He helped rewrite the copy so that I sounded more fun, though not as fun as Jack wanted me to sound. There was an immediate response in the inbox. ‘Reading between the lines, I think you’re holding out for something unusual,’ one said. ‘I believe I’m atypical. For a start I don’t have a television. When I had one I spent a lot of time shouting at it.’ I replied that I couldn’t bear to watch Question Time either. ‘No, no,’ he said. ‘Countryfile, for instance. Countryfile’s really annoying.’ I asked him what he did in the evenings. He said he spent a lot of time with his lizards.

It was a grim Tuesday night, the rain lashing down. I went in search of someone friendlier. There were lots of men who claimed to be the life and soul of the party, but who looked like serial killers on Wanted posters. In general, using a bad passport photograph to illustrate your page isn’t the best of all possible plans. I rummaged through the first five candidates the system had offered and had a look at what they had to say. ‘Scientific facts are never true. If you know why scientific facts are never true, you might be the girl for me.’ ‘Still looking for the right one, a woman who won’t expect me to be at her beck and call.’ ‘Second hand male, in fairly good condition despite last careless owner.’ ‘I am a complex person, too complex to explain here, a hundred different men in one. If you want a dull life you are wasting your time. Move along – nothing to see here.’ ‘Looking for intelligence, co-operation and a natural blonde.’ (Co-operation?)

Perhaps, I thought, I should narrow the search, by ticking some of the boxes for interests. A search based on ticking ‘Current Affairs’ brought up a raft of virtue-signallers. ‘I’m dedicated to the pursuit of justice for all and hate political unfairness.’ ‘The top three things I hate are liars, deceit and war.’ (Whereas, presumably, the rest of us are assumed to approve of wars and lying.) Then I had a brief conversation with a man who said he loved world cinema. I messaged him asking what kind of films he liked. Back came the reply: ‘Hi thanks for asking, my favourite movies are Driller Killer, The Lair of the White Worm, Cannibal Holocaust, I Spit on Your Grave, Cabaret and The Blood-Spattered Bride.’

The first dinner offer came from Trevor, an American expat in London. Trevor had been dumped and was only just passing out of denial and into acceptance, he said. He was doing the work (the therapeutic work on himself, he meant), but was finding it hard. Four thousand words of backstory followed this statement, and in return, I gave him mine. A few hours after this another great long email arrived, talking philosophically about life and quoting writers. It was charming, endearing; I reciprocated with my own thoughts, quoting other writers. We were all set. Then, the day before dinner, Trevor cancelled. The last line of his message said: ‘To be honest, I’m not interested in a woman who’s my intellectual equal.’ (I know this sounds as if it might not be true, but I’m sorry to tell you that it is.) He added that he felt honesty was the best policy. I didn’t like to tell him what my policy was, but right then and there it could easily have involved a plank, a pirate ship, a shark-infested sea and a long pointy stick.

The first real-world meeting was for a coffee in town in the afternoon with an HR manager, between his meetings: a short, sharp interview that I failed. I didn’t mind too much. He was pursed-mouthed, unforthcoming, with dyed black hair and the demeanour of a vampire. Determined to exorcise the bad first date, I agreed to another, with an apparently jaunty tax specialist. Ahead of me in the queue, he bought only his own cappuccino and cake, leaving me to get mine, and then for twenty minutes I heard all about the many, many times he’d seen U2, told one concert at a time. By then my cup was empty. In all sorts of ways my cup seemed to be empty.

It wasn’t just the bad dates that were ending badly. I had a good date that also ended badly: a success so tremendous – dinner that led into dancing, and after that a walk by the river, and then a glorious snog – that I couldn’t sleep afterwards, but lay awake imagining our life together, a fantasy outcome put to an end by his cutting me dead. Sometimes people have one great date with someone and that’s enough for them. A series of great first dates is all they’re hoping for; that’s all they need. I hadn’t anticipated this, not anything like this. I came from a much more straightforward, more traditional dating culture in which people got together at discos and parties and via friends of friends, and stayed together for a long time. We were open with one another, back then, and love was fairly simple.

I decided that what I’d do was establish a real friendship with men, over email and text and sometimes even over the phone (I’ve never liked the phone), before agreeing to meet them. Talking people into being interested in you before meeting – that’s where you might expect the internet to excel. That could be a process designed to work in a middle-aged woman’s favour, circumventing the shock of her physical self when a man met her in person. Undeniably, I had been a shock to some men I’d met, and I wasn’t the only one to have had that experience (look, I’m not particularly hideous). I’d been talking to other women of around my age who had found the very same. It was agreed that there were notable (noble) exceptions, but in general men had expectations that a woman who’d ‘put herself out there’ would dedicate time, effort and money to her appearance, so as to compete. Some men are of the opinion that the whole physical manifestation of a woman on the earth should amount to an A–Z of efforts to please, and that we’re all madly in competition with one another. There are men who think that’s all that lipstick means. There are tabloid newspapers that suggest that’s all that clothes mean, and who divide women into goat and sheep camps, the frumpy and those who flaunt themselves. There have been men, in the course of this quest, who have been openly scandalised about my lack of commitment to looking younger. But then as Jack kept telling me, ‘Men are visual creatures.’ He was doubtful about the Scheherazade strategy, one involving telling stories and general email-based bewitchment. Nonetheless, I resolved to stick with plan A. I decided that I would be quirky, and bright, and a little bit alpha, and I was going to be my real age, for as long as it took. Initial disappointments wouldn’t deter me. I was going to beat the system and find the man I’d want to be with for the rest of my life. I was just hoping it wouldn’t take another 1001 nights.