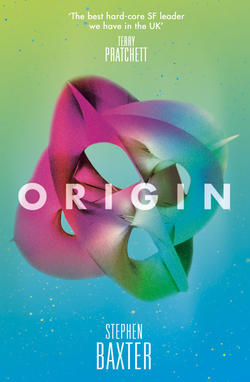

Читать книгу Origin - Stephen Baxter - Страница 6

ОглавлениеPREFACE

Emma Stoney:

Do you know me? Do you know where you are? Oh, Malenfant …

I know you. And you’re just what you always were, an incorrigible space cadet. That’s how we both finished up stranded here, isn’t it? I remember how I loved to hear you talk, when we were kids. When everybody else was snuggling at the drive-in, you used to lecture me on how space is a high frontier, a sky to be mined, a resource for humanity.

But is that all there is? Is the sky really nothing more than an empty stage for mankind to strut and squabble?

And what if we blew ourselves up before we ever got to the stars? Would the universe just evolve on, a huge piece of clockwork slowly running down, utterly devoid of life and mind?

How – desolating.

Surely it couldn’t be like that. All those suns and worlds spinning through the void, the grand complexity of creation unwinding all the way out of the Big Bang itself … You always said you just couldn’t believe that there was nobody out there looking back at you down here.

But if so, where is everybody?

This is the Fermi Paradox – right, Malenfant? If the aliens existed, they would be here. I heard you lecture on that so often I could recite it in my sleep.

But I agree with you. It’s powerful strange. I’m sure Fermi is telling us something very profound about the nature of the universe we live in. It is as if we are all embedded in a vast graph of possibilities, a graph with an axis marked time, for our own future destiny, and an axis marked space, for the possibilities of the universe.

Much of your life has been shaped by thinking about that cosmic graph. Your life and, as a consequence, mine.

Well, on every graph there is a unique point, the place where the axes cross. It’s called the origin. Which is where we’ve finished up, isn’t it, Malenfant? And now we know why we were alone …

But, you know, one thing you never considered was the subtext. Alone or not alone why do we care so much?

I always knew why. We care because we are lonely.

I understood that because I was lonely. I was lonely before you stranded me here, in this terrible place, this Red Moon. I lost you to the sky long ago. Now you found me here but you’re leaving me again, aren’t you, Malenfant?

… Malenfant? Can you hear me? Do you know me? Do you know who you are? – oh.

Watch the Earth, Malenfant. Watch the Earth …

Manekatopokanemahedo:

This is how it is, how it was, how it came to be.

It began in the afterglow of the Big Bang, that brief age when stars still burned.

Humans arose on an Earth. Emma, perhaps it was your Earth. Soon they were alone.

Humans spread over their world. They spread in waves across the universe, sprawling and brawling and breeding and dying and evolving. There were wars, there was love, there was life and death. Minds flowed together in great rivers of consciousness, or shattered in sparkling droplets. There was immortality to be had, of a sort, a continuity of identity through copying and confluence across billions upon billions of years.

Everywhere humans found life: crude replicators, of carbon or silicon or metal, churning meaninglessly in the dark.

Nowhere did they find mind save what they brought with them or created no other against which human advancement could be tested.

They came to understand that they would forever be alone.

With time, the stars died like candles. But humans fed on bloated gravitational fat, and achieved a power undreamed of in earlier ages. It is impossible to understand what minds of that age were like, minds of time’s far downstream. They did not seek to acquire, not to breed, not even to learn. They needed nothing. They had nothing in common with their ancestors of the afterglow.

Nothing but the will to survive. And even that was to be denied them by time.

The universe aged: indifferent, harsh, hostile and ultimately lethal.

There was despair and loneliness.

There was an age of war, an obliteration of trillion-year memories, a bonfire of identity. There was an age of suicide, as even the finest chose self-destruction against further purposeless time and struggle.

The great rivers of mind guttered and dried.

But some persisted: just a tributary, the stubborn, still unwilling to yield to the darkness, to accept the increasing confines of a universe growing inexorably old.

And, at last, they realized that something was wrong. It wasn’t supposed to have been like this.

Burning the last of the universe’s resources, the final down-streamers lonely, dogged, all but insane – reached to the deepest past …