Читать книгу A Failed Political Entity' - Stephen Kelly - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

‘I Am a Man of Northern Extraction’: The Genesis of Haughey’s Attitude to Northern Ireland, 1945–1966

‘When I talk about Ireland I am talking about something that is not yet a reality, it is a dream that has not yet been fulfilled.’

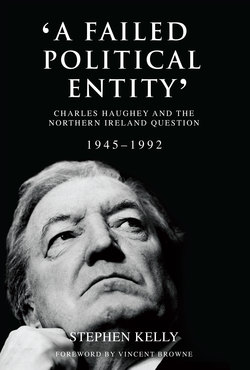

[Charles J. Haughey, circa 1986]1

‘My ancestral home’: Haughey’s Ulster background

The origins of Charles J. Haughey’s lifelong disgust at the partition of Ireland must be understood within the context of his Ulster background. Haughey was born in Castlebar, Co. Mayo on 16 September 1925. He was the third son of Seán Haughey, a commissioned officer in the Free State Irish army and his wife Sarah, whose maiden name was McWilliams. Haughey had three brothers, Pádraig (Jock), Seán and Eoghan and three sisters, Bride, Maureen and Eithne.

Haughey’s parents were not originally from Co. Mayo but from across the recently constituted north-south border, from the republican area of Swatragh in Co. Derry, Northern Ireland. His parents’ families had lived in the vicinity of Swatragh for generations, also referred to as ‘Fenian Swatragh’, according to Fr Eoghan Haughey, Charles Haughey’s older brother.2 Haughey was particularly proud of his association with Swatragh. ‘Swatragh’ was as he put it, ‘my ancestral home.’3 On a visit to Derry in 1986, Haughey recalled with pride that: ‘My father and mother were born here…my people have lived here for a very long time.’4 In later life he would intermittently return to Derry, where he enjoyed ‘coming back to renew childhood associations and to be among my cousins’.5

His father, Seán, had joined the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in 1917 and was involved in the Irish War of Independence in Ulster. By 1921 he was brigade commandant of 4th brigade, 2nd Northern division of the IRA.6 In July 1922, as the Irish Civil War entered its darkest hour, Haughey joined the newly constituted Free State Irish army as a commissioned officer, commanding the 4th infantry battalion, western command, stationed at Castlebar, Co. Mayo.7 It was during the early stages of the Civil War that he was reputed to have smuggled a consignment of rifles from Donegal to Derry, on the orders of Michael Collins, commander-in-chief of the Free State army and chairman of the provisional government.8 Haughey’s mother Sarah was also involved in the Irish Revolutionary period, having been a member of Cumann na mBan during the War of Independence. Her family remained close to the IRA thereafter; her brother, Pat McWilliams, was interned during the Second World War in Northern Ireland.9

In 1928, Seán Haughey resigned from his post in the Irish army due to ill-health, joining the reserve of officers; he was finally discharged from the Irish military on 30 December 1938.10 Following his resignation he did not involve himself in politics on either side of the Irish border. Speaking in 2006, shortly before his death, however, Charles Haughey admitted that his father had been ‘a committed supporter of Cumann na nGaedheal’, and that he was ‘very [Michael] Collins’.11

In the wake of Seán Haughey’s resignation from the Irish army the family settled for a time in the northside suburb of Sutton, Co. Dublin, before moving to a 100-acre farm in Dunshaughlin, Co. Meath. The farm, however, could not be retained when Seán developed multiple sclerosis. In 1933, the Haughey family settled in a new corporation house in Donnycarney, on the corner of Belton Park Road and Belton Park in Dublin. During his school years, Charles Haughey was educated at the Christian Brothers’ primary school, Scoil Mhuire, in Marino and later St Joseph’s Christian Brothers’ Secondary School in Fairview.12

Throughout the 1930s, Haughey regularly visited Co. Derry, where he spent time living with his grandmother (during this period he briefly attended primary school at Corlecky near Swatragh). It was during these visits that he witnessed the sectarian riots of 1935 in Maghera, Co. Derry, and the heavy-handed approach of the Ulster Special Constabulary or the so-called ‘B Specials’.13 His family home in Donnycarney was a hive of activity during this period, with Northern Ireland politics the focus of much debate. Indeed, his parents are remembered for regularly keeping an ‘open house for friends and visitors from the North’.14

The fact that the Haugheys retained a strong interest in the affairs of Northern Ireland went against the general political trend of the period. The vast majority of people living in the south of Ireland never gave Northern Ireland more than a passing thought. Although many refused to admit as much in public, privately a perception prevailed amongst the Irish populace that Northern Ireland was a foreign, alien land. Haughey was only amongst a small percentage of his generation to truly appreciate the Northern Ireland situation and particularly the plight of the Catholic minority. In later life he would regularly recall with fondness how his family were ‘deeply embedded in the Northern Ireland situation’.15

The first-hand encounters that Haughey experienced as a child on his visits to Northern Ireland and the stories that he heard while listening to his parents, left a lasting impact on how he viewed the partition of his country and more generally his attitude to Anglo-Irish relations. His personal connections with Ulster, its history, the land and the people, always remained close to his heart. It is this closeness, this understanding of the northern way of life that imbued his political thinking and nurtured his lifelong and deep-rooted republicanism. He was immensely proud of his northern background. Addressing Dáil Éireann in 1964, for instance, he proclaimed with gravitas: ‘I am a man of northern extraction!’16

It was Haughey’s love for Ulster and a wish to see Ireland united that instilled in him a lifelong antipathy for the Irish border, both in its physical and psychological existence. ‘The fact that my roots are here [in Derry]’, he said in the 1980s, ‘makes the whole border thing preposterous to me. I can never [arrive at the border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland], without experiencing deep feelings of anger and resentment’, the whole situation he felt was ‘nonsense’. He continued:

This border is only there for sixty years, it’s an artificial line that runs across and divides in two a country which has always been regarded as one, and which has always regarded itself as one. It runs through the main street of towns and villages and divides farmyards, even. It separates neighbour from neighbour.17

Haughey’s hatred for the partition of Ireland needs therefore to be understood within the context of his personal connections to Ulster. His father and mother and their respective families all resented having to live in Northern Ireland, which they believed to have been artificially created by the British government under the terms of the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It was this sense of injustice that created and fed Haughey’s anti-partitionism. For the remainder of his lifetime he instinctively remained a vocal opponent of what he would later describe as the ‘failed political entity’ that was Northern Ireland.

Burning the Union Jack: the young Haughey and Northern Ireland, 1940s

By all accounts Haughey enjoyed his teenage years; academically he was diligent, while on the sports field he was fearless. During the early 1940s he represented the Leinster Colleges in hurling and Gaelic football. His notorious temper made an early appearance during this period when he was suspended for a year for striking a linesman while playing for Parnell’s GAA club. In 1943, on coming first in the Dublin Corporation scholarship examination, Haughey attended University College Dublin (UCD), where he studied commerce, graduating with an honours degree in 1946.18

Apart from a promising academic future, following in the footsteps of his father, Haughey also had his sights set on a possible military career. In September 1941, as the Second World War entered its third year and the threat of a foreign invasion increased, Haughey joined the Local Defence Forces (LDF), based in Collinstown battalion. He was platoon leader from November 1943 until he left the LDF in March 1946. In June of the following year he was commissioned in the Fórsa Cosanta Áitiúil (FCÁ),19 as 2nd lieutenant.20 In February 1953 he was promoted to lieutenant, eventually becoming officer commanding ‘A’ company, North Dublin battalion.21 During this period he gave serious consideration to pursuing an army career. However, he eventually resigned from his post in the FCÁ in 1957 on being elected as a TD.22

It was during these formative years that Haughey’s republicanism first boiled to the surface. On VE Day, 8 May 1945, he was notoriously involved in the burning of a Union Jack. The sequence of events leading to this incident is difficult to decipher, but a general picture can be pieced together. At 2pm the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) formally announced the Allied victory over Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich following the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany. Thousands of people lined the streets along Dublin’s main thoroughfares to celebrate the Allied victory. Trinity College Dublin (TCD) soon became the centre for ‘an impromptu celebration’.23

According to an account by the Irish Times at approximately 2.30pm, fifty to sixty students appeared on the roof of TCD’s main entrance, waving Union Jacks and singing ‘God Save the Queen’, ‘Rule Britannia’, ‘There’ll Always be an England’ and the French national anthem.24 By this juncture, the celebrations had attracted between 200–300 onlookers, with many people breaking into chorus, singing the British national anthem. The crowd around College Green increased further when TCD students hoisted three flags from the flag staff, in ascending order: a Union flag, a USSR flag and lastly a French flag.25 One eyewitness, Mr G.W. Chesson, described the atmosphere as being jovial, with the temper of the crowd said to have been ‘friendly’.26

By 3.15pm, however, the mood of the assembly darkened. ‘Booing and cat-calls’, now accompanied the singing.27 A section of the crowd took particular offence to the fact that when the three flags were re-hoisted the Irish Tricolour was placed at the bottom. Ernest A. Alton, provost of TCD, conceded privately at the time that there was ‘no doubt that an insult was offered to the tricolour’.28 In retaliation, at approximately 3.30pm, a number of youths arrived at College Green ‘from the direction of O’Connell Street’, carrying what was described as a Catholic Emancipation flag. Subsequently, one of the group climbed the tramway standards outside Messrs Fox’s Tobacconist Shop, ‘and tying a small Union Jack to the support-wire, proceeded to set it on fire and burn it, amidst howls of derision from the students on the College roof’.29

In response, according to Chesson’s account, a TCD student opened one of the windows in the front of the college and ‘thrust out a stick upon which were hanging three garments of lady’s underwear, coloured – green, white and orange’.30 A group of TCD students then took down the hoisted Irish Tricolour and attempted to set it on fire. Unable to set the flag on fire the TCD students ‘rolled it up and threw it down into the fore-court in front of the wicket gate of the College’.31 Immediately there was a rush of people who rescued the Irish flag.32

News of this fracas soon reached UCD students in Earlsfort Terrace. It was reportedly Haughey who organised a counter demonstration and led a march of UCD students, some allegedly ‘bearing Nazi swastika flags’, to TCD.33 According to Bruce Arnold, it was Haughey, along with a friend, Seamus Sorohan (law student and future barrister), who ripped down a Union Jack that was hanging on a lamp-post at the bottom of Grafton Street and proceeded to burn it.34 It was at this stage that ‘the attitude of the crowd became really ugly’,35 and some within the crowd, including several young women, reportedly made several attempts to break into TCD.36

The rioters rushed the front gates and made it through the main entrance, but were stopped by a large number of Civic Guards from ‘entering the College courtyard’. There were three or four baton charges before ‘the vicinity of the College was cleared’.37 Eventually, the Gardaí were forced to intervene, however, the melée continued towards the direction of the Wicklow Hotel, where several young men attacked the building, with cries of ‘Give us the West Britons’.38 It was further reported that a section of the crowd broke away and later stoned the residence of the British representative and the offices of the United States Consul-General. In total, twelve people were treated at Mercer’s Hospital for slight injuries.39

Haughey’s actions during this brief but memorable riot reflected a prevailing anti-British mood among many Irish people at the time; unlike the unscrupulous young Haughey, however, very few people would have actually been involved in burning a Union Jack. Although ‘neutral’ – Éire did not officially take part in the war effort – the country did suffer. Economically, Ireland was crippled by trade restrictions with the result that the country, as Haughey himself recounted, was effectively ‘down to subsistence level’.40 There was extensive unemployment and rationing, censorship of the press, private motor cars virtually vanished from the roads and sustained emigration.

Apart from blaming Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil wartime administrations for their cultural, economic and social woes, many living in Ireland, including Haughey, vented their anger and frustration towards the British government in London. Indeed, in Ireland, under the banner of the IRA, there existed a small Republican fringe movement who hoped for a Nazi victory over the Allies, clinging to the worn-out idiom that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.’ As on VE Day, such pervasive feelings of Anglophobia occasionally transfixed the Irish psyche. Indeed, Martin Mansergh later noted that during this period Haughey certainly held some ‘personal hang-ups’ regarding British–Irish relations and retained a strong sense of Anglophobia.41

With the war at an end Haughey’s attention quickly shifted to his employment prospects. Having ruled out a career in the Irish army he decided to put his commerce degree to best use. Following his graduation from UCD in 1946 he was articled to the accountancy firm Michael J. Bourke of Boland, Bourke and Company. In 1948 he won the John Mackie memorial prize of the Institute of Chartered Accountants (ICA). The following year, after studying at King’s Inns, he was called to the bar, but never practiced. He became an associate member of the ICA in 1949 and a fellow in 1955.42 It was towards the end of the 1940s, as his burgeoning career in the world of accountancy progressed, that Haughey’s interest with Irish politics and specifically with Fianna Fáil first surfaced. Although he had no traditional Fianna Fáil roots, through his friendship with two former classmates at St Joseph’s, Harry Boland (with whom he established a successful accountancy practice, Haughey and Boland in 1951) and George Colley, that Haughey’s political career first began.

Shortly before his passing in 2006, Haughey recalled with some amusement that his involvement in politics was ‘accidental’. He noted that he fell into politics through his close friendship with Boland and Colley. ‘It was as simple as that,’ he said.43 Haughey’s reluctance to join Fianna Fáil prior to this period may have also stemmed from not wishing to upset his father, who was known to have ‘despised’ Éamon de Valera.44 Following the death of his father in 1948, however, Haughey was convinced by Boland and Colley to join them in the Fianna Fáil Tomas Ó Cléirigh cumann, Dublin North-East.45 Haughey was an active member of cumann affairs from the start. With other young members he became involved in the writing of a pamphlet, Fírinne Fáil, on Fianna Fáil policy and outlook.46 In September 1951, he cemented his links with Fianna Fáil, following his marriage to Maureen Lemass, the eldest daughter of Seán Lemass, a co-founder of the organisation.

Haughey’s rising fortunes as an emerging protégé within Fianna Fáil, coupled with being the son-in-law of the second most powerful man in the party, did not, however, ensure his immediate breakthrough into national politics. At the 1951 Irish general election and again in 1954, he unsuccessfully ran as a Fianna Fáil candidate in Dublin North-Central. In 1953, he was, however, co-opted onto the Dublin Corporation; although he had to suffer the ignominy of losing his seat on the Corporation in the local government elections in 1955. Despite numerous disappointments on the national stage, by 1954, Haughey, now twenty-nine years old, had steadily climbed the Fianna Fáil ladder in his own constituency of Dublin North-East, securing the position as honorary secretary of the Tomas Ó Cléirigh cumann and also honorary secretary of the Dublin Comhairle Dáilceanntair.47

‘Guerrilla warfare’: the Tomas Ó Cléirigh cumann memorandum on partition, 1955

It was Haughey’s prominent role with the Tomas Ó Cléirigh cumann that exposed the true extent of his visceral anti-partitionism.48 In January 1955, in his capacity as honorary secretary of the Ó Cléirigh cumann, Haughey sent a memorandum devoted to the subject of partition to Fianna Fáil headquarters.49 A six-page typed document, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum on partition offered an aggressive case as to why Fianna Fáil should use physical force to secure Irish unity.50 If it had been made public, its contents would have proved highly controversial. It was produced in response to Seán Lemass’s determination to revitalise the Fianna Fáil organisation following the party’s general election defeat in May 1954, and in the context of the renewed IRA activity along the North–South border during this period.

After the 1954 election which resulted in Fianna Fáil’s relegation to the opposition benches, Lemass was appointed as the party’s national organiser. He led a team with responsibility for formulating and developing new policy initiatives, pruning the organisation of any dead wood and listening to what policy areas truly mattered to grass-roots members.51 As part of this consultative process between September 1954 and January of the following year, Lemass contacted every registered Fianna Fáil cumann throughout the Irish Republic, requesting they submit any views that its members had on either local or national issues.52 It was in response to this request that on 15 January 1955, Haughey sent the aforementioned memorandum to the Fianna Fáil national executive.

Besides Haughey, the Ó Cléirigh cumann contained several influential Fianna Fáil members: Cork-man, senator Seán O’Donovan (chairman of the cumann); George Colley, a future deputy leader of the party; his father Harry Colley, TD for Dublin North-East; Oscar Traynor, also a TD for Dublin North-East; and Harry Boland, brother of Kevin Boland and son to Gerald Boland.53 Unfortunately, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum is not signed, therefore one will never be able to state definitively that Haughey wrote or co-wrote it. Nonetheless, the fact that it was written in the plural, suggests that its contents represent the collective viewpoint of the members of the Tomas Ó Cléirigh cumann.54

The very fact that Haughey, in his capacity as honorary secretary of the Ó Cléirigh cumann, sent the memorandum directly to the Fianna Fáil national executive reinforces the argument that he most likely endorsed its contents.55 Moreover, the memorandum’s ‘military’ tone, focused on guerrilla warfare tactics, included attacks on key military and strategic installations in Northern Ireland, which adds weight to the argument that Haughey had a part to play in its formation. At this time he was a FCÁ officer, commanding ‘A’ company, North Dublin battalion. Over the previous several years, initially in the LDF and later the FCÁ, he had amassed a wealth of military knowledge, an unusual trait for the time.

Oral testimonies also provide circumstantial evidence to support the claim that Haughey played a role in the formulation of the Ó Cléirigh memorandum. Although Haughey’s son, Seán Haughey, remains adamant that ‘there is nothing to suggest’ that his father contributed to the Ó Cléirigh memorandum, there is contrary evidence to suggest otherwise. In correspondence with this author, Seán Haughey stated that there is no copy of the Ó Cléirigh memorandum on partition in the private papers of Charles J. Haughey. He instead suggested that George Colley was the possible author.56 Two former members of the Ó Cléirigh cumann, however, disagree with Seán Haughey’s claim.

In a 2008 interview Harry Boland, a member of Ó Cléirigh cumann during the period in question, said he would be ‘very surprised’ if Haughey did not produce the Ó Cléirigh memorandum. He explained that Haughey and Colley worked closely with one another and although he could not recall the memorandum in question, both men were in charge of policy development.57 Mary Colley, wife to George Colley, was ‘convinced’ that Haughey and her husband devised the Ó Cléirigh memorandum. In a 2009 interview she recalled that the two men would spend hours together discussing Northern Ireland, and she remembered that Haughey came to her home on several occasions during late 1954 and early 1955, where, she believed, he and Colley formulated the memorandum.58

The Ó Cléirigh memorandum was produced in the aftermath of the 1954 Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis, held in October of that year. The catalyst was Éamon de Valera’s public acknowledgement during his presidential address that without the consent of Ulster unionists he was unable to offer any credible solution for ending partition.59 Furthermore, the Fianna Fáil leader categorically rejected the use of force to secure Irish unity.60 To the amazement (and disgust) of some of those present, he admitted that he did not think it ‘is possible to point out steps’ that would ‘inevitably lead to the end of partition’.61 He went as far as to inform Fianna Fáil delegates that ‘our efforts to make for a solution of that sort have come to nought’.62

De Valera’s speech, as reported by the Irish Times, did not have the support of a number of ‘wild men’ within Fianna Fáil.63 Harry Boland, who was in attendance during the 1954 Ard Fheis, recalled that ‘many young folks within Fianna Fáil had become disillusioned’ because so little progress was being made to end partition. He remembered that at this Ard Fheis a cohort of delegates, particularly those of a younger age, openly expressed their frustration at the lack of action on partition from the Fianna Fáil hierarchy.64 Boland remarked that along with Haughey and Colley, he felt that ‘nothing was happening on the North’ and that the time had arrived to initiate a fresh approach to partition.65 Indeed, the previous September 1954, on behalf of the Ó Cléirigh cumann, Haughey issued a resolution requesting that ‘the [Fianna Fáil] National Executive submit to the Ard Fheis proposals for a positive line of action on partition’.66

It was with this sense of despondency and frustration that members of the Ó Cléirigh cumann penned the memorandum. Its central thesis was the advocacy of physical force as a legitimate method to secure Irish unity. Its preamble declared that de Valera’s recent Ard Fheis speech, ‘made it clear’ that partition could not be ended by ‘diplomatic measures’. Therefore, the only ‘policy open to us which gives reasonable hope of success’, it explained, was the use of force.67 ‘Outside the Organisation’, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum declared:

There is a noticeable and growing discontent with National Inaction in relation to Partition. This Cumann believed that this feeling is particularly widespread even at present, and that the question of Partition will become a major issue for the younger generation of Irish people, at any rate within the next five years ... At present, young people who feel strongly on this question of Partition have not outlet [sic] for their feelings of national outrage except the IRA ...We believe it is the duty of the Fianna Fáil Organisation to provide the leadership and the organisation of such national feeling, and that if it should fail to do so, it will be responsible for the consequences.68

In the context of understanding the genesis of Haughey’s attitude to Northern Ireland, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum offers fascinating evidence, which has only come to light in recent years.69 Four recommended policies stand out for particular attention. First, the memorandum suggested that the Irish government, in conjunction with the Irish army, should enact a campaign of guerrilla warfare in Northern Ireland. It argued that:

An important preparation would, of course, be in the military sphere. While there is a reasonable hope that negotiations could be forced before the necessity for military action arose, nevertheless it would be criminally negligent to embark on the campaign without having made preparations in our power to deal with every contingency likely to arise. In this connection, we advocate the lying-in of the greatest possible stocks of arms and ammunitions suitable for guerrilla warfare, the closest possible study of British military installations likely to be of particular importance in relation to the areas in which the campaign will be carried out ...70

The Ó Cléirigh memorandum envisaged that the Irish government-sponsored guerrilla warfare campaign would concentrate its resources on one or two areas in Northern Ireland with Catholic majorities (probably situated in counties Derry and Armagh). It noted that the following advantages could hence be won:

(a)From the point of view of the international propaganda, we can claim that we are merely trying to enforce the will of the people in the area; and

(b)The area or areas concerned being contiguous to the Border can be more easily dealt with and kept in communication with the other portion of the Six-Counties.71

It explained that an objection to this policy might be advanced on the grounds that the ‘concentration of our efforts on one or two nationalist areas would be tantamount to the abandonment of the remainder of the Six-Counties’. ‘Such an argument,’ it noted, ‘would be unrealistic, since there is ample precedent for a step-by-step policy in our past history, e.g. the taking over of the ports was not regarded as an abandonment of our claim on the Six-Counties.’72

Second, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum proposed that once the guerrilla campaign was underway that the Irish government, with the support of Northern Ireland Catholics, should commence a campaign of civil disobedience (in those selected areas). Such a campaign, it noted:

Should be controlled and directed by the Irish Government, either openly or secretly. The object of such a campaign would be to create an international incident which could not be ignored by the British Government. The campaign would be based on that adopted by Sinn Féin, i.e. non-recognition of British or Stormont sovereignty in the area or areas selected; non-recognition of the Courts, and the setting-up of ‘Sinn Féin’ Courts; the withholding of rates and taxes...73

Indeed, at the 1954 Fianna Fáil Ard Fheis, during a private meeting, Colley had asked de Valera’s opinions on the possibility of creating an ‘incident on the border’, which would bring international attention to partition. De Valera was quick to reject Colley’s hypothesis. He rhetorically inquired if Colley would be prepared to be a ‘G [Green] Special’, who like the B-Specials, would have to enforce the rule of law on the Protestant population of Northern Ireland?74

The campaign was to be based on that adopted by Sinn Féin during the War for Independence. Paradoxically, the concept of arranging a programme of civil disobedience had also been considered by the leaders of the IRA in the run up to the renewed activity of the mid-1950s, but the army council decided under Seán Cronin’s influence to opt for a guerrilla campaign.75

Third, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum explained that Northern nationalists or ‘local forces’ should be organised and supplied with arms and ammunition. It was envisaged that these ‘local forces’ would:

Work in conjunction with the Army in making simulated and diversionary attacks on British military installations if required, plans for the destruction of official British and Stormont records in regard to rates and taxes in the selected areas, etc. It would of course be essential to organise nationalist opinion in the Six-Counties in general and in the selected areas or areas in particular. We believe that given a positive policy with full support from the South, both materially and spiritually, the necessary co-operation will be obtained from the Northern Nationalists.76

The similarities between the IRA campaign at the time and the proposals put forward by the Ó Cléirigh memorandum were interesting. Both advocated a method of guerrilla warfare against their ‘oppressors’. This entailed a policy of the destruction of vital communications and a concentration of superior numbers of men at a decisive time and location. To foreshadow events in the near future, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum’s reference to the importance of British military installations was to become a key aspect of the IRA’s ‘Operation Harvest’ campaign. The campaign commenced in 1956, focusing on the destruction of British transmitter posts, road and rail and any ‘enemy’ vehicles that were found.77

Finally, the Ó Cléirigh memorandum also envisaged the establishment of a committee to examine social welfare, education, industry, taxation and ‘current laws that would be necessary upon the anticipated assimilation of one or two of the border counties of Northern Ireland and in the eventual reunification of Ireland’.78 It noted that:

A committee of experts on International Law should also be asked to advise on the legal effect of open support by the Irish Government of persons engaged in the campaign of civil disobedience; the question of the use of our regular armed forces in Six-Counties; and aiding and possibly arming of irregular forces on active service in Six-Counties, etc. and the pointing out of loopholes whereby difficulties involved can be overcome. In this connection, your attention is drawn to the action of the Egyptian Government, which unofficially organised a liberation army, consisting of irregular volunteers, but which is believed by many to have consisted mainly of regular army units.79

The contents of the Ó Cléirigh memorandum and Haughey’s leading role in its formation, provides compelling, if not conclusive, evidence that he believed that the use of physical force to secure Irish unity, in the right circumstances, represented legitimate Fianna Fáil policy. Furthermore, it reveals that since at least the mid-1950s, he harboured a deeply conceived ideological commitment to securing a united Ireland.

This memorandum is all the more significant when one seeks to understand the rationale behind Haughey’s decision-making process during the Arms Crisis of 1969/1970; a subject examined in detail in the following chapter. His calls around the Irish cabinet table in August 1969 for the Irish army to cross into Northern Ireland and his involvement in supplying Northern Catholics with guns and ammunition were extremely similar to those policies articulated in the Ó Cléirigh memorandum some fifteen years previously.

The well-trodden argument that when the conflict erupted in Northern Ireland in the summer of 1969, Haughey’s actions were dictated solely by political opportunism, that prior to this period he ‘had shown no signs of republican sympathy’ (except for his VE Day protests in 1945), is false.80 Of course, Haughey saw the developments in Northern Ireland in 1969 as a perfect opportunity to further his objective of securing the leadership of Fianna Fáil. Yet, as is argued in the next chapter, this is only part of the story of Haughey’s lifelong association with the Northern Ireland question.

The Ó Cléirigh memorandum offers a unique insight into the mind of Haughey as he entered his early thirties. Like so many of his generation, by the mid-1950s he had become disillusioned and impatient by the empty promises routinely offered by Irish politicians such as de Valera. Haughey believed that the older generation within Fianna Fáil had become complacent on the subject of partition, that the party had abandoned its number one aim to secure a united Ireland. In a fashion that would become synonymous with his leadership qualities in later life, Haughey was no longer content to fudge the issue, to keep the subject of partition away from public scrutiny. On the contrary, he wanted to get the job done. He wanted action. Acknowledging this conviction helps to explain his role in formulating the Ó Cléirigh memorandum. If Fianna Fáil’s peaceful endeavours to end partition, in the words of de Valera, had thus far ‘come to nought’, then Haughey believed that the alternative option, the use of physical force, was a legitimate solution.

A lost opportunity: Haughey and Fianna Fáil’s standing-committee on partition matters, 1955

The response from the Fianna Fáil hierarchy to the Ó Cléirigh memorandum on partition is unknown. Lemass, however, decided that the Fianna Fáil leadership had a responsibility to clear up any confusion regarding the party’s official stance on Northern Ireland. As noted above, during this period, a small, but vocal, minority within Fianna Fáil had publicly criticised the party’s perceived inability to make any inroads on partition and were particularly aghast by de Valera’s public admission at the 1954 party Ard Fheis that it was not ‘possible to point out steps’ that would ‘inevitably lead to the end of partition’.81 Consequently in November 1954 at a meeting of Fianna Fáil’s national executive, on Lemass’s suggestion, an agreement was reached that de Valera would nominate a committee to ‘deal with all aspects of the matter [partition]’.82 The committee was to become known as the ‘standing-committee on partition matters’.83

Early the following year, in January 1955, Cork-man Thomas Mullins, the so-called ‘third-grandfather’84 of Fianna Fáil and general secretary of the organisation, sent letters to Lemass, Frank Aiken, Seán Moylan, Seán MacEntee, Kevin Boland, Liam Cunningham, Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Feehan and, significantly, Haughey. The letters notified the eight men that on de Valera’s instructions each had been appointed to a new standing-committee on partition matters.85 The members were a mixture between the old brigade of Fianna Fáil and a new breed of the party’s members, commonly referred to in political circles as ‘Mohair-suited Young Turks’.

Lemass was appointed chairman of the standing-committee. The presence of Aiken, MacEntee and Moylan on the committee was predictable. These three Fianna Fáil TDs (except for de Valera and Lemass) had held the most influential portfolios in previous Fianna Fáil governments. Liam Cunningham’s appointment had more to do with geography than anything else. He was a border-county Fianna Fáil deputy for Inishowen, Donegal North-East – an essential factor if the committee was to have credibility among party deputies. Subsequently described by the British Embassy in Dublin as holding extremely strong views on partition,86 in December 1954, Cunningham wrote to Fianna Fáil headquarters to request that the organisation make a greater effort to end partition.87

The presence of Boland and Feehan on the standing-committee was further example of Lemass’s determination to bring some ‘new blood’ and ideas into Fianna Fáil. During the early months of 1954 they had been appointed to the party’s organisation committee with the task of helping Lemass with his plan of revamping the party. Kevin Boland, son of Fianna Fáil stalwart and party TD for Roscommon Gerald Boland,88 was a well-respected figure within the party for his hard-working ethos and was elected to the organisation’s committee of fifteen at the 1954 Ard Fheis. Feehan, a founding member of the Sunday Press, was known to be close to Lemass. In late January 1954, on the instruction of Mullins, Feehan produced a memorandum outlining his views on partition.89 Five pages in length, the majority of his points were consistent with Fianna Fáil’s strategy towards Northern Ireland at the time, namely, that the use of force to secure Irish unity was ‘out of the question’ and that concessions would therefore need to be offered to Ulster unionists.90

The decision by the Fianna Fáil leadership to appoint Haughey on the standing-committee is interesting. Like Boland and Feehan he too had been appointed by Lemass to Fianna Fáil’s organisation committee the previous year. As noted above, in January 1955 (the same month he was appointed to the standing-committee on partition matters) Haughey had sent the Ó Cléirigh memorandum on partition to the Fianna Fáil national executive. Although it is difficult to decipher, the circumstantial evidence would suggest that on reading the Ó Cléirigh memorandum on partition Lemass, alarmed by its content, decided to appoint Haughey to the standing-committee in order to ‘educate’ his son-in-law on the futility of violence in the attainment of a united Ireland. Indeed, before the inaugural meeting of the standing-committee on partition-matters, Lemass ordered that each member receive a copy of the Ó Cléirigh memorandum.91

Between the first meeting of the standing-committee in early February 1955 and the second gathering in early April, detailed research was carried out by the committee members concerning Fianna Fáil’s Northern Ireland policy.92 Stemming directly from the two meetings, a thought-provoking memorandum was produced by Lemass and his colleagues. The memorandum recorded that committee members, including Haughey, fully endorsed the proposals contained within and instructed the Fianna Fáil national executive to ‘issue a statement on Partition on the following lines or alternatively to incorporate such a statement in any publication dealing with Fianna Fáil’s policy and programme’.93

The memorandum proposed eight practical policies that Fianna Fáil should follow vis-à-vis Northern Ireland. The points represented a victory of pragmatism over dogma. It categorically ruled out the use of force, instead insisting that only peaceful means could deliver the Holy Grail of Irish unity. At the heart of the memorandum was the thesis that only through a process of co-operation and mutual respect between Belfast and Dublin could the long-term attainment of a united Ireland be achieved. The memorandum’s preamble declared:

It was the purpose of Fianna Fáil to advocate and apply the following policy towards the realisation of the primary aim of the national effort as set out above

1.To maintain and strengthen wherever possible, all links with the Six-County majority, especially economic and cultural links, to encourage contacts between the people of both areas in every field, and to demonstrate that widespread goodwill for the Six-County majority can be fostered by such contacts;

2.To discourage and prevent any course of action which would have the effect of embittering relations between the people of both areas, or making fruitful economic and cultural contacts more difficult;

3.To keep constant in mind, in relation to all aspects of Twenty-Six County internal policy and administration, the prospect of the termination of partition and so to direct them as to avoid or minimise the practical problems that may arise when partition is ended;

4.To eliminate as far as possible all impediments to the free movement of goods, persons, and traffic across the Border and particularly to alter the Customs Law so as to permit of the entry into the Twenty-Six-counties free of Customs duty and subject to no more onerous conditions than apply to Twenty-Six County products, all goods of bona fide Six-County origins;

5.To encourage the establishment of joint authorities to manage affairs of common interest, including transport, electricity generations and distributions, sea lights and marks, drainage programmes and tourist development;

6.To co-ordinate with the Six-County authorities in arrangements for Civil Defence, including movement of population from threatened areas in time of war;

7.To arrange, if possible, with the Six-County authorities for joint commercial and tourist publicity abroad, and to invite periodic consultation of all such matters of common interest;

8.To urge on the people of the Twenty-Six-counties the desirability of giving to the Six-County majority of such assurances as to their political and religious rights in a United Ireland as may reasonably be required, and as to the maintenance of local autonomy in respect of such matters as may be desired by them.94

Points one to three were consistent with current Fianna Fáil thinking on Northern Ireland and maintained that the ‘concurrence of wills’ philosophy was the only viable method available to the party to secure Irish unity; that Dublin must work in tangent with London and Belfast, via economic, cultural, political and social contacts, if partition was to be successfully ended.95 Points four to seven originated from Lemass’s personal views on the economic practicalities between North and South. Specifically, he believed that Fianna Fáil must agree to the lifting of tariffs between Dublin and Belfast, thus creating a free trade area on the island of Ireland.96

Lastly, point eight dealt with the thorny subject of making changes to the Irish Constitution in order to help accommodate Ulster unionists into a united Ireland, based on a federal agreement, namely, that a review of Article 44 of the Irish Constitution should be undertaken – this dealt with ‘the special position of the Catholic Church’. Additionally, the committee recommended that Articles 2 and 3, which claimed territorial jurisdiction over the whole of the island of Ireland, might be amended. Lemass was one of a few within Fianna Fáil to appreciate that the combination of Catholic social values and the territorial claim to the whole of the island, as enshrined in the 1937 Irish Constitution, had cemented the alienation of Ulster unionists over the previous two decades, thus entrenching partition.97

On 6 April 1955, Lemass sent de Valera the standing-committee’s memorandum and proposed that the national executive should endorse the recommendations as official Fianna Fáil Northern Ireland policy.98 Within twenty-four hours, however, de Valera rejected his lieutenant’s recommendation. In a letter to Lemass, dated 7 April, de Valera said that ‘whilst I agree a great deal of it does not seem to be open to serious objection, some of the steps suggested are not so, and are of more than doubtful value’. De Valera explained that the memorandum ‘... would certainly give rise to very serious controversy’ and would possibly add further confusion amongst ‘the nationalists of the Six-Counties’. He, therefore, informed Lemass that its contents must be ‘kept as a private norm. Publicity might in fact defeat the purpose of the scheme’.99

De Valera’s rejection of the memorandum was not altogether surprising. While he favoured a federal solution to help bring an end to partition he would have never signed up to the standing-committee’s recommendation that Fianna Fáil consider revising Articles 2 and 3. After all, de Valera was the main instigator of the 1937 Irish Constitution, which had in effect withdrawn the de facto recognition of the 1925 boundary agreement between the Dublin and Belfast governments, by asserting the thirty-two county national claim. More immediate concerns may have also instructed de Valera’s thinking. Following a recent spate of IRA violence, publication of the proposals would have left Fianna Fáil open to further criticism that it had abandoned its traditional republican pledge to secure a united Ireland.

Despite de Valera’s rejection of the proposals, the seeds of change had been sown. Lemass was to later acknowledge that the craft of policy development was a slow process that was ‘never born complete with arms and eyes and legs overnight. It’s something that grows over a long time’.100 In fact, the proposals contained within points four to eight, for instance, were ten years ahead of their time and were remarkably similar to the policies that Lemass advocated when he became Fianna Fáil leader and taoiseach in 1959; a subject considered in further detail towards the end of this chapter.

There is no archival information available to ascertain Haughey’s attitude to the memorandum or indeed his general involvement on the standing-committee on partition matters. The fact that Lemass acknowledged that the memorandum had the support of all committee members suggests that Haughey towed the committee-line and gave his backing to the standing-committee’s recommendations. In reality, even if he did not agree with all of the proposals, he had little room to manoeuvre. Although by this period Haughey held a local corporation seat in Dublin, he was a marginal figure within the Fianna Fáil organisation at large. His contribution to the standing-committee, one can therefore argue, would have been curtailed by Lemass and the other elder statesmen such as Aiken, MacEntee and Moylan. In fact, by the time Haughey secured his first ministerial portfolio as minister for justice in 1961, he was widely believed to be a firm supporter of Taoiseach Lemass’s consolatory, economically inspired, Northern Ireland policy.

‘Nothing to fear in a united Ireland’: Lemass, Haughey and Northern Ireland, 1959–66

Haughey’s breakthrough into national politics eventually happened at the 1957 Irish general election when he was elected a Fianna Fáil TD for North-East Dublin. He was to retain this seat for the rest of his political career. His success came at the expense of Harry Colley, who lost his seat after thirteen years as Fianna Fáil TD. Colley’s election defeat accelerated the personal enmity between Haughey and George Colley, which steadily grew over the subsequent years. With Fianna Fáil back in government following three years in the political wilderness, Haughey learned his trade on the party’s backbenches.

The only apparent reference that Haughey made to Northern Ireland during his initial years as a backbencher TD came in the summer of 1957. During a debate in Dáil Éireann in July of that year regarding the commencement of the IRA border campaign (1956–62), he urged Independent TD for Roscommon Jack (John) McQuillan to point out what constitutional steps could help to deliver a united Ireland.101 Apart from this incursion Haughey rarely involved himself in the Northern Ireland question. In fact, his initial performance during the early years was unremarkable, fulfilling the role as a mere spectator in Dáil Éireann. Over time, however, he soon grasped the political nettle. In the mould of his father-in-law, Haughey concerned himself mostly with economic affairs. His contributions to debates were generally focused on the need for direct foreign investment, lower direct taxation and urban and rural redevelopments.

Éamon de Valera’s decision to retire as Fianna Fáil leader and taoiseach two years later, in June 1959, was the indirect catalyst to Haughey’s political career. Upon de Valera’s announcement the spotlight immediately turned on who would replace him as Fianna Fáil president. Lemass was the obvious candidate. At fifty-eight years of age he was viewed as the most realistic and practical man in the government, with a sound grasp of economics. Indeed, the result of the succession race was never really in doubt, even if there was a little discontent among a select few deputies.102 After the furore of de Valera’s election as president of Ireland, the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party and the national executive gathered on 22 June 1959 to elect a new leader. Seán MacEntee duly proposed, and Frank Aiken seconded, Lemass as the second leader of Fianna Fáil.103 Soon after the national executive met to ratify the decision104 and the following day Lemass was officially elected taoiseach by the Dáil.

It did not take long for Haughey’s family connections with the most powerful man in the country to pay off. In May 1960, although apparently against Lemass’s advice to his son-in-law, Haughey was appointed parliamentary secretary to the minister for justice, Oscar Traynor (Traynor was known to be unhappy about Haughey’s appointment).105 Haughey embraced his new role with the kind of energy that became characteristic of his political style. He soon gained a reputation as an able and confident speaker, a politician you could rely on for ‘getting things done’, as the British Embassy in Dublin subsequently recounted.106 Within the space of several months he introduced and steered through the Dáil, several pieces of legislations, ranging from the Rent Restrictions Bill to the Civil Liability Bill.

The fruits of Haughey’s labour soon paid off. Following the 1961 Irish general election, which Fianna Fáil won, Haughey was appointed minister for justice, following Traynor’s retirement from mainstream politics. Haughey immediately threw himself into his first ministerial portfolio. He implemented a major programme of legal reform, including the 1962 Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Act, the 1964 Succession Act and the abolition of capital punishment for the majority of offences.107 Despite their subsequent animosity towards one another, Peter Berry, secretary of the Department of Justice, later noted that of the fourteen ministers he had served under in the Department of Justice, Haughey was by far the most able.108 Indeed, Haughey’s future political arch-nemesis, Garret FitzGerald, later recounted that the former was an ‘excellent minister, particularly in Justice’.109

Apart from a crusade to modernise and reform Ireland’s legal field, Haughey is best remembered during this period for helping to suppress the IRA border campaign, which had been ongoing since 1956. Following Fianna Fáil’s return to government in October 1961, Lemass was determined to tackle the IRA head on. Although he commanded only a minority position in the Dáil, he considered Fianna Fáil’s position safe enough to wage a campaign against the illegal organisation. Throughout 1961 the IRA carried out a number of horrific murders. On 27 January, the movement shot dead a young Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) corporal, Norman Anderson. This was followed by further IRA attacks throughout 1961. The most brutal of these was carried out in November, when the movement ambushed an RUC police patrol in Jonesborough, Co. Armagh. During the ambush an RUC policeman, Constable William Hunter, was killed.110 These attacks, which were an increasing source of embarrassment for the Irish government, reinforced Lemass’s opposition to physical force republicanism.

In response to the renewed IRA campaign, the Irish government, led by Lemass and Haughey, reactivated the Special Criminal Courts by filling vacancies created by retirements or deaths.111 The minister for justice orchestrated a publicity campaign portraying the IRA as an illegal organisation that, in his words, did not ‘serve the cause of national unity’.112 Although Haughey referred to the deep resentment felt by the people in the Irish Republic to partition, he condemned as ‘foolish’ any attempts to secure a united Ireland by force.113 The government’s propaganda offensive proved successful and by the early months of 1962 public sympathy for the IRA had waned. In February of that year, realising the futility of its military campaign, and the general public’s apathy, the IRA leadership issued orders for the movement to ‘dump arms’.114 As Barry Flynn noted: ‘So in February 1962, the curtain fell on a campaign that had failed, and failed utterly to achieve any of its primary objectives.’115

Haughey’s role in bringing the IRA border campaign to an end fitted in nicely with Lemass’s more conciliatory approach to Northern Ireland, as compared to his predecessor de Valera. Lemass’s appointment as taoiseach in 1959 raised hope to a new generation of Fianna Fáil supporters that he ‘would cast aside the ghosts of the past and deal with Irish unity, not as a theoretical aspiration, but as a long-term reality’.116 Significantly, under Lemass, partition and economic policies became intrinsically linked as he adapted Fianna Fáil’s traditional approach towards Northern Ireland to the new economic realities of the 1960s. Guided by one central motivation, the Irish economy, his entire approach to Northern Ireland was based on securing support from Ulster Unionists for his wish to establish a free trade area between Dublin and Belfast.

The Irish government’s 1958 programme for economic expansion, inspired and implemented by the secretary of the Department of Finance, T.K. Whitaker, emphasised the importance of an open market free trade area between Ireland and the United Kingdom. Particular emphasis was placed on dismantling the Irish protectionist regime in preparation for European Economic Community (EEC) membership.117 This new initiative had ramifications for partition. Lemass believed that the first step in securing a free trade area between the Republic and Great Britain was the dismantling of Dublin’s protectionist system against Belfast within the island of Ireland.118 Throughout Lemass’s reign as Fianna Fáil leader, Haughey rowed in behind his father-in-law’s Northern Ireland policy. As part of Lemass’s drive for cross-border co-operation between North and South, Haughey also supported the taoiseach’s occasional use of the term ‘Northern Ireland’ rather than the ‘Six Counties’. Since the early years of the Irish Free State the standard practice in political and administrative circles in the South of Ireland was the constant usage of the term ‘Six-Counties’ to refer to Northern Ireland. This formula was an easy way for politicians in the Irish Republic to propagate their non-recognition of the Northern Ireland state. Although Lemass had no intention of succumbing to Ulster Unionist demands that Northern Ireland should be recognised de jure as part of the United Kingdom, he ‘did want to deal with the political realities of North and South relations’.119

In correspondence with Vivion de Valera, in May 1960, Lemass explained that the use of terms like ‘Belfast government’, ‘Stormont government’, had been the ‘outcome of woolly thinking on the partition issue’.120 If Ulster Unionists were to ever agree to enter a united Ireland based on a federal solution (with a subordinate Northern Ireland parliament in Belfast), he argued that it was nonsensical that the Irish government continued to refrain from using the title ‘government of Northern Ireland’. It was, therefore, merely ‘common sense that the current name would be kept’.121 Haughey followed a similar line of argument in correspondence with the minister for external affairs, Frank Aiken, in 1967. The Irish government, Haughey explained, ‘should introduce a greater degree of flexibility in our practice by permitting the use, as occasion may require, of the terms “Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland”’. Irish politicians, he wrote, ‘needed to take a less rigid line in the matter of nomenclature’.122

Haughey’s general endorsement of Lemass’s Northern Ireland policy can be ascertained by his support for the taoiseach’s personal crusade to build a bond of mutual trust with the political force of Ulster Unionism, specifically the taoiseach’s attempt to officially accord de facto recognition to Northern Ireland. As part of Lemass’s ambition to commence direct talks with Northern Ireland prime minister, Terence O’Neill, Haughey was involved, to quote Mary Colley, with a ‘gradation of initiatives’ with Ulster Unionists throughout the mid-1960s in the hope that it would ‘open up a new way’ via-à-vis Fianna Fáil’s official stance on Northern Ireland.123

To understand Lemass’s approach to Northern Ireland, it is important to lay emphasis on his indirect and private initiatives to bring about a revision of Fianna Fáil’s traditional Northern Ireland policy. Central to this approach was Lemass’s use of senior Fianna Fáil elected representatives. On two separate occasions during 1962, Lemass sent two of his leading government frontbenchers, minister for commerce and industry, Jack Lynch and Haughey to Northern Ireland on separate kite-flying exercises. The aim of their respective visits to Belfast was to reopen a debate on the commencement of cross-border trade between North and South, in the light of the end to the IRA border campaign.

In February, within days of the IRA announcing an end to their campaign, Lynch spoke at a debate on North–South relations at Queen’s University Belfast. He expressed the Irish government’s desire to establish an all-Ireland free trade area for goods of Irish and Northern Ireland origins.124 It was a policy publicly advocated by Lemass since becoming leader of Fianna Fáil in 1959.125 Later that year in November, Haughey spoke at a debate organised under the auspices of the New Ireland Society, again at Queen’s University Belfast. Proposing the motion that ‘minorities have nothing to fear in a united Ireland’, Haughey said that Protestants had nothing to fear if Ireland was united as the ‘Constitution of the Irish Republic guaranteed freedom of religion to every citizen’.126 Haughey was following Lemass’s policy that the religious division between the two communities would need to be tackled before Protestants would agree to enter a united Ireland based on a federal model. Significantly, both speeches failed to mention the delicate issue of the recognition of Northern Ireland. Instead, Fianna Fáil ministers fostered the idea that economic co-operation should be independent of recognition.127

By early 1963 it was apparent that the sending of Fianna Fáil ministers to Northern Ireland had proved ineffective. Lemass realised that Belfast would not agree to cross-border co-operation until Dublin offered concessions on the thorny and sensitive issue of recognition of Northern Ireland. Lemass therefore decided to act. On the night of 16 April 1963, Fianna Fáil TD for Dublin North-East, George Colley spoke at a major symposium on North–South co-operation. Significantly, Colley’s speech was the first occasion that a Fianna Fáil elected representative officially granted de facto recognition to Northern Ireland.128 Although never publicly acknowledging that he was the instigator of Colley’s speech, the circumstantial evidence does confirm that Lemass did instruct his backbench colleague to speak on the subject of recognition. By doing so Lemass believed he could bypass Ulster Unionists’ demand for the formal de jure recognition. With the recognition debate resolved, Lemass hoped to focus instead on cross-border co-operation.129

To Lemass’s disappointment, O’Neill quickly poured cold water on the prospect of North–South co-operations. Speaking at Stormont he categorically ruled out ‘general discussions so long as the Dublin government refused to recognise the constitutional position of the Six-Counties’.130 Confronted by another rejection from Belfast for cross-border co-operation prior to Dublin granting de jure recognition to the Northern Ireland state, Lemass decided to personally intervene. Addressing a gathering of Fianna Fáil supporters in Tralee, Co. Kerry in July 1963, Lemass said:‘We recognise that the government and parliament there exist with the support of the majority in the six county area – artificial though that area is.’131 While not recognising Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom de jure, Lemass did accord de facto recognition to the state. Lemass now waited for a response from O’Neill.

The Northern Ireland prime minister, however, was slow to respond to the taoiseach’s overtures. Ironically, O’Neill’s decision to eventually succumb to Lemass’s advances was not as a result of Dublin’s latest initiative, but because of ongoing infighting within the Ulster Unionist party; with minister for commerce, Brian Faulkner, being O’Neill’s main antagonist.132 In December 1964, in a preconceived attempt to out-manoeuvre O’Neill, Faulkner expressed his willingness to meet the minister for industry and commerce, Jack Lynch, to discuss North–South trade.133 An invitation that Lynch suggested he would be willing to accept in the early months of 1965.134 O’Neill read the signals. He feared that Faulkner would steal the political headlines by becoming the first Unionist politician to meet a minister from the Republic since the mid-1950s.135

Here lay the seeds for the famous Lemass–O’Neill meeting of January 1965. To Lemass’s surprise in early January of that year, O’Neill instructed his private secretary, Jim Malley, to invite Lemass to Belfast. On the morning of 14 January 1965, Lemass and Thomas Kenneth (T.K.) Whitaker left Dublin for Belfast. At 1pm, the Irish party arrived in Belfast and was greeted by O’Neill at his official residence at Stormont. The agenda for the meeting provided a comprehensive list on cross-border issues; importantly, it avoided discussions on political and constitutional matters, careful to respect the jurisdiction of the Northern Ireland government. The meeting with O’Neill was a milestone in Lemass’s Northern Ireland policy.

Ten years after first compiling a comprehensive list of possible areas of cross-border co-operation between Belfast and Dublin (as contained within the memorandum produced on behalf of the Fianna Fáil standing-committee on partition matters in 1955), Lemass now sat face-to-face discussing those very same items with the prime minister of Northern Ireland. During his one-hour meeting with O’Neill, the men discussed tourism, education, health, industrial promotion, agricultural research, trade, electricity and justice matters.136 Lemass must have found the entire episode a rewarding experience, after so long in de Valera’s shadow, he was in a position to fully implement his economically motivated Northern Ireland strategy.

The available evidence supports the argument that Haughey, who was appointed minister for agriculture in October 1964, endorsed Lemass’s trip to Belfast. On originally receiving the invitation from O’Neill, Lemass had telephoned his minister for external affairs, Frank Aiken. Although somewhat surprised, like Haughey, he too fully supported Lemass’s plan to meet O’Neill.137 Besides Aiken, Lemass informed two other unknown cabinet ministers of his impending visit to Belfast.138 It is not clear whether Haughey was one of the unnamed ministers. Jack Lynch was certainly not aware of Lemass’s visit to Northern Ireland; he later recalled that Lemass had kept the planned trip to Belfast strictly confidential.139

Unfortunately, given the nature of the Irish cabinet minutes there is no official record of ministers’ reaction to Lemass’s announcement of his intent to travel to Belfast.140 Members of Lemass’s cabinet differ in their recollection of whether or not he informed the government before he met O’Neill. Haughey recalled that Lemass did raise his planned meeting with O’Neill, but he did not permit a debate on the subject.141 Minister for local government, Neil Blaney subsequently noted that Lemass, in fact, did not raise his scheduled meeting with O’Neill with his cabinet colleagues.142 Blaney’s observations seem inadmissible, considering he did not attend the last cabinet meeting, on 12 January, prior to Lemass’s trip to Belfast.143

During the remainder of January and February 1965, Lemass sought to put his discussions with O’Neill on cross-border co-operation into action. On 4 February, Lynch and Erskine Childers (minister for transport and power) held separate meetings with Northern Ireland minister for commerce, Brian Faulkner, in Dublin, on issues relating to cross-border trade and tourism. On 9 February, cross-border relations reached a further highpoint when O’Neill travelled to Dublin to meet Lemass for a second summit meeting. This was the first occasion that the prime minister of Northern Ireland had visited Dublin in an official capacity since Sir James Craig had met Michael Collins in 1922. O’Neill was warmly received by Dublin. Accompanied by his wife, he had lunch with Lemass, Aiken and Lynch at Iveagh House. Following lunch, discussions commenced with a general informal conference on cross-border relations.144

Following the Lemass–O’Neill meeting there was a flurry of ministerial meetings between Irish and Northern Ireland ministers both in Belfast and Dublin. On 12 February, Haughey met his ministerial counterpart from the Northern Ireland Department of Agriculture, Harry West, in Dublin. Although this was a social encounter, with wives present at a dinner in Haughey’s home in Raheny, it was a sign of how far relations between Dublin and Belfast had moved on.145 The very fact that the two governments had commenced discussions on cross-border issues at ministerial and civil-service level was noteworthy, ‘signifying the commencement of a policy of normalisation in North–South relations which only a few years before seemed unattainable’.146

Indeed, on 9 February, Haughey had stood in for Lemass at a debate at Queen’s University Belfast, held under the auspices of the Literary and Scientific Debating Society. During the course of his speech, Haughey laid out some of his vision for the future of North–South co-operation on agricultural matters and more generally on the ‘future of Irish politics’. Apart from focusing on his support for food processing, he spoke of the need to break down barriers between North and South. It was ‘the function of politics’, he said, ‘to reconcile, to bring together and so to create an atmosphere in which men could give of their best to’.147 Haughey was eager to convert his own words into concrete actions. In March and again in May of 1965, he held further talks with Harry West.148

Haughey’s attitude towards Northern Ireland during this time was determined by the ongoing Anglo-Irish Free Trade Area negotiations (the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement was eventually signed on 14 December 1965) and ultimately the Irish government’s desire to secure membership of the EEC. Like Lemass, Haughey strongly favoured Ireland fostering closer ties with Europe in anticipation of the country’s eventual membership of the EEC. The minister for agriculture made his views clear during a speech at the Irish Club in London on St Patrick’s Day, 17 March 1965.

As Haughey delivered his speech to assembled dignitaries, including the British prime minister, Harold Wilson, he must have considered how far he had travelled along the political path of reconciliation. His escapades in helping to burn a Union flag in 1945 must have seemed a distant memory. Two decades on, he was now a respected statesman, propagating to his audience the merits of cordial British–Irish relations, in the context of his support for British and Irish membership of the EEC. European integration, he explained during the course of his speech, was the best avenue for the economic prosperity of both neighbouring countries. ‘Ireland,’ he said, should ‘go forward into the future with Britain in a spirit of mutual co-operation.’ In reference to Ireland’s past, but with his sights firmly focused on the future, he noted that Dublin and London had a responsibility to respect the history and traditions of one another and not to be afraid to challenge long-held stereotypes and misconceptions.149

During the Irish general election campaign of April 1965, Haughey and his ministerial colleagues continued to endorse the merits of European integration and to encourage further co-operation between Belfast and Dublin.150 By now Haughey’s influence over Fianna Fáil was steadily growing. He was Fianna Fáil’s national director of elections during this election campaign (and again at the 1969 general election) and heavily involved in revamping the party’s fund-raising capabilities.151 During the 1965 election campaign, Lemass felt particularly confident that his meetings with O’Neill would be viewed as a positive factor by the Irish electorate. However, as in previous elections, the economy, not Northern Ireland, dominated the election trail. When the election results were announced, on 13 April, Fianna Fáil won exactly half the seats, seventy-two, a gain of two seats. The result did not give Lemass the overall majority that he desperately wanted. The close result, as noted by John Horgan, suggests that without the Northern issue he might have been forced into another minority government.152 Despite the narrowness of the election victory, Fianna Fáil returned to government for the third successive occasion, with Haughey retaining his portfolio as minister for agriculture.

In June 1966, Lemass informed close friends of his intention to resign as taoiseach and Fianna Fáil president.153 After serving nine years as taoiseach and a further twenty-one years as a Fianna Fáil minister, Lemass, who was sixty-seven years old, had grown tired of the day-to-day hustle and bustle of political life. On 9 November of that year, he notified a gathering of the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party of his intention to resign. He asked deputies to offer ‘no sympathetic speeches’.154 Lemass’s announcement left his cabinet colleagues shocked. Seán MacEntee was outraged by his leader’s decision. He could not believe that the taoiseach should ‘wash his hands of responsibility for the country’s affairs’.155 Frank Aiken was likewise upset. He recorded that he had tried his ‘utmost to persuade him [Lemass] to carry on at least for another few years’.156

Attention quickly turned to who would succeed Lemass. The choice ranged across a broad spectrum within Fianna Fáil. Haughey was believed to have a good chance, as was George Colley, Neil Blaney and Jack Lynch. Haughey, however, did have one major handicap in the ongoing farmers’ protests.157 It was believed that Lemass favoured Lynch as his successor, Colley his second. Initially, Lynch refused to be considered for the leadership, with the result that Colley and Haughey emerged as the early favourites. However, Blaney then threw a spanner in the works by announcing his intention to run.

The prospect of Haughey becoming Fianna Fáil president set off alarm bells among many of the old guard within Fianna Fáil. Again Aiken led the protests. He believed that under Lemass’s leadership Fianna Fáil had already become too cosy with big business. Aiken particularly disliked Fianna Fáil’s decision in 1966 to establish Taca, a fund-raising organisation of 500 businessmen, who each paid relatively large sums of monies and in return obtained privileged access to Fianna Fáil ministers and exclusive dinners in the Gresham Hotel, Dublin.158 Haughey, together with Brian Lenihan and Donogh O’Malley, the so-called ‘three musketeers’, embodied Fianna Fáil’s cosy relationship with the business world. Writing in 1965 (little doubt in reference to this new breed of ‘Mohair-suited Young Turks’ taking over Fianna Fáil) Gerald Boland noted that ‘Some of the young set make me actually sick and disgusted.’159 Indeed, privately Boland even went so far as to describe Brian Lenihan as ‘a shit’.160

In the eyes of men like Aiken and Boland, Taca was indicative of Fianna Fáil’s ‘moral collapse’.161 Many of the party stalwarts detested the idea of ministers aligning themselves with a ‘golden circle’ of builders, property developers and speculators, all of whom benefited greatly from the economic boom of the 1960s. Aiken was particularly concerned by accusations that some senior Fianna Fáil figures had abused planning laws, ‘with inside information lubricating the accumulation of substantial private fortunes’.162 Aiken believed that if Haughey secured the Fianna Fáil leadership, the organisation’s pathway to moral bankruptcy would be inevitable. Aiken’s concerns were no doubt alerted because of Haughey’s ability during this period to acquire considerable personal wealth without the apparent means to do so.

Aiken, therefore, announced his support for Colley in the leadership contest. He then tried his ‘utmost to persuade’ Lemass to carry on for another few years in order to allow Colley sufficient time to gain further ministerial experience and to raise his national profile.163 In many ways Colley was the complete opposite to Haughey. The former represented the traditional-wing of the party; he had a love of the Irish language and a reputation as a decent and honest politician. Haughey, on the other hand, was widely known for his love of money. He represented the brash, progressive and at times snobby, new breed of politician who had infiltrated Fianna Fáil during the 1960s.

The prospect that a leadership battle might lead to a split within the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party spurred Lemass to ask Lynch a second time if he would stand. After consulting his wife, Maureen, Lynch agreed. As soon as Lynch announced his intension to run for the leadership Haughey withdrew from the contest, as did Blaney. Encouraged by Aiken, Colley decided to remain in the contest. On 9 November 1966, the Fianna Fáil parliamentary party met to vote for the new president of the organisation. A vote was taken on Lemass’s successor so as to avoid, as the records of the meeting phrase it, ‘acrimonious discussions and intemperate statements that could cause unnecessary division in the party’.164

Aiken ‘spoke at length’ and said that ‘the decision they were to make that day would be a momentous one’. He told party members that he was ‘firmly convinced that George Colley had something to give the nation’ and objected to what he called the ‘tyranny of consensus’ through which attempts had been made to vote Lynch as Fianna Fáil leader.165 Despite Aiken’s protests in the end the contest between Lynch and Colley was a one-sided affair. When the votes were counted Lynch was declared as the new Fianna Fáil leader, beating his rival on a margin of fifty-two votes to nineteen. The following day, on the morning of 10 November 1966, Lemass announced to the Dáil chamber his resignation as taoiseach. He offered no fancy pretentious speech, but simply recorded with his customary fondness for brevity: ‘I have resigned.’166

In conclusion, with Lemass’s retirement, relations between Dublin and Belfast were at their most cordial since that of the Cumann na nGaedheal government’s dealings with Ulster Unionists during the early 1920s. However, the honeymoon period was to be short-lived. Unfortunately, old agendas and prejudices were to soon return. Whitaker, writing in the 1970s of Lemass’s visit to meet O’Neill in 1965, recalled with poignant accuracy how quickly the political landscape of the island of Ireland changed within the space of a few years: ‘We started back on the road to Dublin with new hope in our hearts. We had no presentiment of the tragic events to 1969 and the years since.’167

By the time of his appointment as minister for justice under the Lemass government in 1961, it seemed apparent that Haughey had replaced his youthful blend of Anglophobia and republicanism with a conciliatory attitude to the political forces of Ulster unionism in Belfast and the British government in London. The illusion, however, was shattered in 1969. As is analysed in the next chapter, the outbreak of the conflict in Northern Ireland in August of that year, was the moment when Haughey’s previously well-hidden, but deep-rooted, anti-partitionist views on Northern Ireland reappeared with dramatic consequences, not merely for his political career, but for the institutions of the Irish state.